Affiliation:

1Department of Chemical Biological Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Ciudad Juárez, Chih. 32315, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8482-7213

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemical Biological Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Ciudad Juárez, Chih. 32315, Mexico

Affiliation:

2Department of Physics and Mathematics, Institute of Engineering and Technology, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Ciudad Juárez, Chih. 32310, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2233-0310

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemical Biological Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Ciudad Juárez, Chih. 32315, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6162-8139

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemical Biological Sciences, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Ciudad Juárez, Chih. 32315, Mexico

Email: nmartine@uacj.mx

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6447-9861

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2025;3:1010102 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2025.1010102

Received: July 05, 2025 Accepted: October 23, 2025 Published: December 03, 2025

Academic Editor: Bruno Alves Rocha, University of São Paulo, Brazil

The article belongs to the special issue Organic and Inorganic Compounds in Foods and Plants from Latin America

Aim: Brosimum alicastrum Sw. (Ramón) seed is an underutilized starch source. Ramón seed starch (RSS) has been partially characterized, showing functional properties superior to corn starch. The modification of native starches is useful for obtaining desirable characteristics. HMT is a physical method that may alter the structure of starch by modifying its interaction with water. The study evaluated the effect of HMT on the chemical composition, morphological characteristics, and functional properties of RSS.

Methods: RSS, corn, and wheat starches were isolated using a wet milling method. The starches were modified with HMT (10%, 20%, and 30% moisture). Chemical composition of flours and native starches was determined using AOAC methods. Total starch was determined by the AACC method, and amylose content was analyzed using the assay with DMSO, Concanavalin A, and amylolytic hydrolysis. Morphological characteristics were observed using scanning electron microscopy. Functional properties [solubility index (SI), water absorption capacity (WAC), and swelling power (SP)] of starches were determined using gravimetric methods.

Results: RSS had higher mineral content (0.9%), total carbohydrates (98.5%), dietary fiber (11.2%), and lower protein content (0.2%) and total starch (82.0%) than wheat and corn starches. RSS yield was 31.2% and showed small granules (6.3 ± 1.4–11.5 ± 1.3 µm), with oval-spherical shape, and typical amylose content (24.9 ± 0.4%). No significant changes were observed in amylose-amylopectin content and morphology of granules after modification. The functional properties of RSS were significantly improved in HMT10%, reducing the peak at 80°C and increasing the SI (18.7 ± 0.8%), WAC (18.1 ± 0.2 g water/g starch), and SP (22.2 ± 0.2 g water/g starch) at 90°C, compared to native RSS, and greater than modified wheat and corn starches.

Conclusions: RSS modified by HMT at 10% moisture gradually enhances its functional properties as temperature increases, and above that of corn and wheat starches, resulting in an attractive non-conventional starch with potential industry applications.

The growing interest in healthy foods has led consumers to demand less processed food products with clean labels and nutritionally enhanced. Starch is one of the main components of the human diet due to its high energy content, besides being considered a highly versatile ingredient in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries [1]. Corn, wheat, rice, and potatoes are the main sources of starch consumed worldwide. Starches from these sources are the most studied and used by the food industry. In recent years, the search for non-conventional starches and new starch sources, underutilized or alternative to traditional crops such as the mango [2], avocado [3], Ramón (Brosimum alicastrum Sw.) [4] seeds, among others, has increased to develop raw materials that could meet the demands for healthier foods [5]. Ramón is a neotropic tree native to Mesoamerica and the Caribbean with a wide distribution in Mexico [6]. The fruit, seed, wood, leaves, and latex from the Ramón tree have been used as sources of raw materials with potential nutritional and functional properties to enrich or fortify foods with low nutritional value, or for the development of functional foods [7, 8]. The Ramón seed flour (RSF) is characterized by high protein content (11.5%), dietary fiber (13%), and starch (63%), in addition to micronutrients [9–11], and has been considered an underutilized natural resource with prominent economic value [12]. There are a few reports of foods elaborated with RSF. Martínez-Ruiz et al. [13] used RSF to develop a beverage targeted at populations with special dietary requirements such as lactose intolerance, gluten sensitivity, and/or caffeine. The beverage showed good nutritional characteristics and was well accepted by consumers. Subiria-Cueto et al. [10] used RSF to improve the nutritional value of wheat flour (WF) tortilla, increasing the dietary fiber content and antioxidant compounds. Also, RSF has been used to develop a beverage and bread (muffin), specially designed for vulnerable groups such as the elderly, with important results in their nutrition and health status [14].

However, studies of the isolation and characterization of starch from the Ramón seed are scarce. Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] isolated and partially characterized native starch from Ramón seed collected in Campeche, Mexico. In this study, a starch yield of 30% was obtained, with oval-spherical and round granules and a diameter of 6.5 to 15 μm. The amylose content (AC) was 25.36%, an amylose/amylopectin ratio of 1:2.94, and a low retrograde tendency. Ramón seed starch (RSS) showed higher gelatinization temperature (above 75°C), transition enthalpy (21.42 J/g), and functional properties [solubility, water absorption capacity (WAC), and swelling power (SP)] than corn starch (CS), suggesting possible applications in food systems requiring high temperatures or in the manufacture of biodegradable materials. In another study, RSS was oxidized with sodium hypochlorite, showing a reduction in its functional properties of solubility and SP compared with native starch [15]. On the other hand, Moo-Huchin et al. [16] reported that RSS exhibits C-type crystals and 30.6% crystallinity with an FTIR band absorbance ratio of 1.14, demonstrating that RSS has a more ordered structure (more crystalline areas) than CS. According to the pasting and rheological properties, RSS presents higher viscosity values (267 BU) at 92°C than CS, and a viscoelastic gel-like behavior with overall Tan D values ranging from 0.08 to 0.34, which is typical of “weak” viscoelastic gels with high elasticity without adopting a rigid structure, suggesting its use as a thickening agent in food, an excipient for drugs, and a biomaterial for food packaging. Native starches may have some limitations, such as a tendency to retrograde, low solubility, thermostability, low freeze-thaw stability, and limited process tolerance, among others, which can make them difficult to use in food processing [17]. Currently, the modification of starches, using different methods, helps adapt or improve their properties and thus expand their industrial applications. Starch modifications can be enzymatic, chemical, physical, or dual, causing structural modifications in the starch for various purposes, including improving technological properties such as gelling and solubility, and increasing resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis [18]. Particularly, physical modification causes changes in the morphology and structure of starch granules, influenced by physical factors such as moisture, temperature, pressure, pH change, radiation treatment, and ultrasonic treatment. However, physical treatments do not modify the D-glucopyranosyl units in the starch polymer and generally generate changes in the packing arrangements of the starch polymer within granules. These changes provoke changes at the same time in the starch properties [19, 20]. The physical modifications do not use chemical reagents compared to chemical modifications; they are safe and environmentally friendly. For its part, chemical modifications have received attention in biomedical fields and wastewater treatment [20, 21]. Physical modifications are divided into thermal treatments, such as heat-moisture treatment (HMT), annealing, microwave heating, osmotic pressure treatment, and heating of dry starch, and non-thermal treatments, such as ultrahigh-pressure homogenizers, dynamic pulsed pressure, pulsed electric field, and freezing and thawing [20]. HMT is one of the most widely utilized and effective physical methods for modifying starch properties that alter the starch structure and change its interaction with water. Starches modified by the HMT method have significantly improved the WAC, increasing their use in various food applications such as thickeners, texture enhancers in baked goods, noodles, and pie fillings, resulting in lower retrogradation rates [22]. To date, no studies have been conducted on the physical modifications of the RSS. We hypothesize that the physical modification of starch isolated from Ramón seeds will enhance its functional properties, thereby expanding its potential applications in food. This study aimed to isolate and modify RSS through HMT and determine its physicochemical, morphological, and functional properties as a non-conventional food ingredient.

RSF was acquired from a technology-based company in Mérida, Yucatán. According to the supplier’s indications, the seed was collected in the southeast of Quintana Roo, Mexico. Corn (Maseca®, Mexico) (CF) and wheat (Selecta®, Mexico) (WF) flours were purchased locally.

Starch isolation was carried out by the method reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4], where 500 g of RSF was mixed with 5 L of sodium bisulfite solution (0.1% w/v) (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) and left to stand for 12 h. Afterward, the pH was adjusted to 10 with 1.0 M sodium hydroxide (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) and allowed to steep for 30 min at room temperature. The suspension was sieved two times through a No. 100 mesh (0.149 mm) (Alcon®, Mexico) and then sieved one last time through a No. 120 mesh (0.125 mm) (Alcon®, Mexico) to ensure maximum extraction of starch. The resulting starch suspension was washed with distilled water three times by re-suspension. After the final wash, the suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 2,500 rpm (Model HN-SII, IEC, USA). The supernatant was discarded, and the starch was dried in a 60°C oven (Model 1324, VWR®, USA) for 24 h. Subsequently, the starch was ground in a commercial homogenizer (600 W, Nutribullet®, USA). The non-starchy residue was frozen for further utilization. The starch powder was stored in airtight containers for further use and analysis. Starches from commercial CF and WF were obtained using the same method.

RSS modification was carried out by HMT, reported by Liu et al. [23]. Briefly, the modification was carried out at three moisture contents: 10%, 20%, and 30%. Starch samples (10 g) with adjusted moisture (adding distilled water) were placed in airtight glass containers and left to stand for 24 h at room temperature. After the equilibration step, the containers were placed in a conventional oven (Model 1324, VWR®, USA) at 120°C for 3 h and cooled in a desiccator. The modified starches were ground in a commercial homogenizer (600 W, Nutribullet®, USA), sieved through a No. 120 mesh (0.125 mm) (Alcon®, Mexico), and stored in airtight containers for further analysis. The same procedure was used for corn (CS) and wheat (WS) starches.

Chemical composition of flours and native starches was performed according to AOAC methods [24]: moisture content was carried out following the oven (Model 1324, VWR®, USA) desiccation procedure (925.10) at 105°C for 5 h; ash was determined by calcination in muffle (Model FE-340, Felisa®, Mexico) (923.03) at 550°C for 5 h; crude fat by Soxhlet method (923.05) (Model 2043, Soxtec™, Foss™, Denmark), total protein by the Kjeldahl method (920.87), (Model RapidStill II, Labconco®, USA), total carbohydrates were determined by difference method and total dietary fiber (TDF) by enzymatic-gravimetric assay (991.43) (K-TDFR-100A, Megazyme®, Ireland). All determinations were made in triplicate.

The total starch (TS) content of flours and native starches was determined by the AACC official method (76.13.01) [25] using an enzyme kit (K-TSTA-100A, Megazyme®, Ireland). For the analysis, 100 mg of the sample was weighed (Model PA163, OHAUS®, Mexico) in a Falcon® tube in duplicate. After, 0.2 mL of 78% ethanol (96%, AZ®, Mexico) was added to aid dispersion, and the Falcon® tube was stirred in a vortex (Model Vortex-Genie 2, Scientific Industries®, USA). A magnetic stirrer (5 × 15 mm) and 2 mL of cold 2 M potassium hydroxide (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) were added to each tube and mixed for 20 min at 4°C in an ice bath. After, the tubes were homogenized in the vortex. Subsequently, 8 mL of 1.2 M sodium acetate buffer (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) (pH 3.8) was added to each tube, and immediately, 100 μL of thermostable α-amylase (K-TSTA-100A, Megazyme®, Ireland) and 100 μL of amyloglucosidase (K-TSTA-100A, Megazyme®, Ireland) were added, mixed well. The tubes were placed in a water bath (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) at 50°C for 30 min with intermittent agitation. The contents of the tubes were transferred to 100 mL volumetric flasks for dilution. Subsequently, 10 mL aliquots were placed in tubes and centrifuged (Model HN-SII, IEC, USA) at 1,800 rpm for 10 min. Next, 12.5 μL of the supernatant and 375 μL of GOPOD (K-TSTA-100A, Megazyme®, Ireland) were placed in a microplate and incubated at 50°C for 20 min in a spectrophotometer (Model xMark, Bio-Rad™, USA). Finally, the absorbance at 510 nm was recorded. The percentage of TS calculation was determined with the following equation [26]:

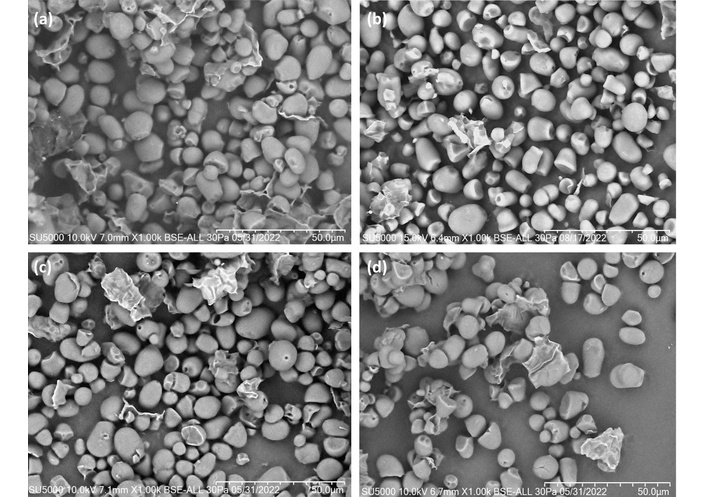

The morphology of native and HMT-modified starches was examined using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (Model SU5000, Hitachi®, Japan). The samples were fixed on a metallic slide secured in a conductive carbon tape; operating conditions were: 10 to 15 kV electron acceleration voltage and 30 Pa pressure at a magnification of 500×, 1,000×, and 1,500× [27].

The AC of native and HMT-modified starches was determined using the amylose/amylopectin assay from Megazyme® (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland) according to the supplier’s instructions. Briefly, starch samples (25 mg) were dispersed entirely with 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) in a water bath (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) at 95°C for 1 min. Then, the tubes were vigorously mixed (Model Vortex-Genie 2, Scientific Industries®, USA) for 2 s and returned to the bath for 15 min. An aliquot (1 mL) of Solution A (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland) was mixed with 0.5 mL Concanavalin A (Con-A) solution (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After, the tubes were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min. Then, 1 mL of the supernatant was transferred to centrifuge tubes and diluted with 3 mL of 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (ACS, Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) (pH 4.5). Samples were heated in a water bath (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) at 95°C for 5 min to denature Con-A. Subsequently, 100 μL of an amyloglucosidase/α-amylase enzyme mixture (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland) was added, and tubes were incubated (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) at 40°C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 5 min. Next, 12.5 μL were placed in a microplate with 375 μL of GOPOD (K-AMYL, Megazyme® Ireland) and incubated in a spectrometer (Model xMark, Bio-Rad™, USA) at 40°C for 20 min. The absorbance of samples at 510 nm was registered. On the other hand, TS was determined by mixing 0.5 mL of Solution A (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland) with 4 mL of 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (ACS Sigma-Aldrich®, Mexico) (pH 4.5) and 100 μL of amyloglucosidase/amylase enzyme mixture (K-AMYL, Megazyme®, Ireland). The mix was incubated at 40°C in a water bath (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) for 10 min. Finally, 12.5 μL of the mix and 375 μL of GOPOD (K-AMYL, Megazyme® Ireland) were placed in a microplate and incubated in a spectrometer (Model xMark, Bio-Rad™, USA) at 40°C for 20 min, and the absorbance at 510 nm was registered. The AC in the starch sample was estimated as the ratio of GOPOD absorbance at 510 nm of the supernatant of the Con-A precipitated sample to that of the TS sample. Afterward, amylopectin content (APC) was calculated by difference, and the amylose/amylopectin ratio was obtained [28].

Solubility index (SI), water absorption capacity (WAC), and swelling power (SP) of native and HMT-modified starches were evaluated by the method reported by Sathe and Salunkhe [29], with a few modifications. For SI, WAC, and SP determinations, 1.0 g of sample was used. Each sample was dispersed in 10 mL of distilled water in a centrifuge tube. The samples were heated at 60, 70, 80, and 90°C in a water bath) (Model Aquabath 18800, Lab-line Thermo Scientific®, USA) for 30 min. Samples were cooled at room temperature and centrifuged (Model HN-SII, IEC, USA) at 3,551 g for 15 min. The tubes were carefully decanted onto aluminum plates, where the weight (Model, PA163, OHAUS®, Mexico) of the decanted solution was recorded before drying overnight at 105°C (Model 1324, VWR®, USA). Finally, the weight (Model, PA163, OHAUS®, Mexico) of the dry residue was recorded to determine SI. For the WAC determination, after centrifugation, the supernatant was removed from the tube, and the gel was weighed (Model, PA163, OHAUS®, Mexico). For SP determination, the gel weight and soluble solids weight from SI were used. All measurements were made in triplicate. The SI, WAC, and SP were calculated with the following equations:

The data were analyzed using a Levene’s test to verify the homoscedasticity. Further, a one-way ANOVA with multiple Fisher (LSD) comparisons was performed. When Levene’s test was significant, the Student’s t-test for unequal variances was used. All analyses were carried out using the statistical program XLSTAT version 2023.3.0 (Addinsoft, Paris, France). The results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

The moisture content varied among flours (WF > RSF > CF), and then the macronutrient data analysis was performed on a dry weight basis. The RSF was characterized by a high content of minerals and dietary fiber, and the total protein content was slightly lower than WF. Also, RSF showed the lowest crude fat and starch content compared to WF and CF. On the other hand, the starch isolated from the flours showed different yields, with WS presenting the highest yield (60.0%), followed by RSS (31.2%), and finally CS (12.0%). Also, a similar tendency in moisture content was observed among the isolated starches (WS > RSS > CS). The chemical analysis in dry weight indicates that RSS presented higher content in minerals, crude fat, total carbohydrates, and dietary fiber than WS and CS. However, WS and CS showed higher protein content compared to RSS (Table 1).

Chemical composition of flours and native starches.

| ID | Moisture(%) | Dry weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash(%) | Total protein(%) | Crude fat(%) | Total carbohydrates(%) | Total dietary fiber(%) | Total starch(%) | ||

| Flour | |||||||

| RSF | 8.9 ± 0.2b | 4.1 ± 0.1a | 13.1 ± 0.3b | 1.3 ± 0.0c | 81.5 ± 0.5b | 22.2 ± 0.2a | 59.6 ± 0.7b |

| CF | 8.6 ± 0.1c | 1.5 ± 0.0b | 9.9 ± 0.0c | 4.6 ± 0.2a | 84.0 ± 0.3a | 11.4 ± 1.3b | 74.3 ± 2.0a |

| WF | 12.5 ± 0.1a | 1.0 ± 0.0c | 13.9 ± 0.2a | 1.6 ± 0.1b | 83.5 ± 0.1a | 3.6 ± 0.1c | 75.3 ± 1.4a |

| Starch | |||||||

| RSS | 8.9 ± 0.2b | 0.9 ± 0.0a | 0.2 ± 0.0c | 0.40 ± 0.0a | 98.5 ± 0.0a | 11.2 ± 0.2a | 82.0 ± 0.4c |

| CS | 7.1 ± 0.1c | 0.6 ± 0.0b | 3.2 ± 0.1b | 0.39 ± 0.0b | 95.8 ± 0.1b | 2.2 ± 0.0b | 94.8 ± 1.0a |

| WS | 9.3 ± 0.1a | 0.4 ± 0.0c | 6.3 ± 0.2a | 0.20 ± 0.0c | 93.1 ± 0.2c | 1.2 ± 0.0c | 83.4 ± 1.0b |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. SD = 0.0 indicate that SD < 0.01. RSF: Ramón seed flour; CF: corn flour; WF: wheat flour; RSS: Ramón seed starch; CS: corn starch; WS: wheat starch. Comparisons among flours or starches. Values in the same column with different lowercase letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

The diameter and shape of the native and modified RSS are shown in Table 2. The RSS granules were generally smaller than corn (CS) and wheat starch (WS) granules. The morphological analysis was carried out considering four size intervals for better understanding: small granule < 50 µm, medium granule 50–100 µm, large granule 101–200 µm, and very large granule > 200 µm.

Morphological characteristics and amylose-amylopectin content of native and HMT-modified starches.

| S | T | Morphology | Amylose(%) | Amylopectin(%) | Amylose/Amylopectin ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter(µm) | Shape | |||||

| RSS | Native | 6.3 ± 1.4–11.5 ± 1.3 | Oval-Spherical | 24.9 ± 0.4b | 75.1 ± 0.4b | 1:3.0 |

| HMT10% | 7.1 ± 1.8–16.2 ± 0.0 | 25.8 ± 0.1a | 74.2 ± 0.1c | 1:2.9 | ||

| HMT20% | 7.3 ± 1.8–14.1 ± 0.8 | 24.3 ± 0.1c | 75.7 ± 0.1a | 1:3.1 | ||

| HMT30% | 8.0 ± 1.2–11.5 ± 1.5 | 25.5 ± 0.2a | 74.5 ± 0.2c | 1:2.9 | ||

| CS | Native | 12.1 ± 1.2–21.8 ± 2.6 | Polyhedral | 28.1 ± 0.2a | 71.9 ± 0.2b | 1:2.6 |

| HMT10% | 12.6 ± 1.5–14.8 ± 1.8 | 27.4 ± 0.4b | 72.6 ± 0.4a | 1:2.7 | ||

| HMT20% | 8.6 ± 1.2–18.7 ± 0.8 | 28.6 ± 0.2a | 71.4 ± 0.2b | 1:2.5 | ||

| HMT30% | 8.3 ± 1.4–16.6 ± 1.1 | 28.5 ± 0.4a | 71.5 ± 0.4b | 1:2.5 | ||

| WS | Native | 12.9 ± 0.9–24.7 ± 3.0 | Spherical and flat circular | 22.1 ± 0.2d | 77.9 ± 0.2a | 1:3.5 |

| HMT10% | 18.8 ± 3.4–23.8 ± 5.6 | 23.2 ± 0.5c | 76.8 ± 0.5b | 1:3.3 | ||

| HMT20% | 11.7 ± 0.2–23.0 ± 3.5 | 24.3 ± 0.5b | 75.7 ± 0.5c | 1:3.1 | ||

| HMT30% | 15.1 ± 1.4–29.1 ± 4.5 | 25.1 ± 0.4a | 74.9 ± 0.4d | 1:3.0 | ||

The two mean ± SD values represent the minimum and maximum mean diameter in the same treatment. S: starch; T: treatments; RSS: Ramón seed starch; CS: corn starch; WS: wheat starch; HMT: heat-moisture treatment. Amylose and amylopectin content were compared among treatments in the same starch. Values in the same column with different lowercase letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

The native and modified RSS granules are shown in Figure 1. The native RSS presented 46.7% of small granules with a mean area of 26.2 ± 13.4 µm2, and 53.3% of starch granules had a medium size with a mean area of 76.3 ± 19.1 µm2 (P > 0.05). On the other hand, in native CS, three size granules were identified: medium (38.8%, mean area: 72.6 ± 11.7 µm2), large (38.8%, mean area: 143.8 ± 26.2 µm2), and very large (22.4%, mean area: 249.2 ± 54.2 µm2) (P > 0.05). The native WS granules were predominantly very large (72.7%, mean area: 359.1 ± 96.4 µm2), and two little fractions: large (18.2%, mean area: 133.1 ± 26.9 µm2) and medium (9.1%, mean area: 81.6 ± 15.0 µm2) (P < 0.01). The HMT with different moisture content slightly increased the proportion and area of small granules in RSS (RSS-10%: 67.6%, mean area 26.7 ± 11.4 µm2; RSS-20%: 66.2%, mean area: 31.3 ± 11.8 µm2 and RSS-30%: 66.0%, mean area: 32.6 ± 11.4 µm2) and two little fractions in medium size granule were observed in RSS-10% and -20% (1.4%, mean area: 133.1 ± 0.0 µm2 and 4.2%, mean area: 115.6 ± 0.1 µm2, respectively) (P < 0.01). This tendency was observed in CS granules, where CS-10% presented 65.0% as medium size (P = 0.04), and CS-20% and CS-30% in medium (37.1% and 56.3%, respectively) (P < 0.01), and large size (42.8% and 31.2%, respectively) (P < 0.01). Also, modified WS granules reduced the proportion of very large granules to 33.3% and 63.3% in WS-10% and WS-20%, respectively, and only in WS-30% was this proportion the highest (87.5%) (P < 0.01). Damage or broken starch granules were observed in all samples; native RSS presented the highest proportion (34.4%) compared to native CS (9.1%) and native WS (15.4%). Different shapes were observed among RSS, CS, and WS (Table 2), and no differences were identified among the native and modified starch granules.

Scanning electron micrographs of Ramón seed starch. (a) Native starch, (b) HMT-modified starch at 10% moisture, (c) HMT-modified starch at 20% moisture, and (d) HMT-modified starch at 30% moisture.

The AC and APC in the starches and the ratio of these two molecules, are shown in Table 2. The native RSS had an intermediate AC, being lower than CS (3.2%) and higher than WS (2.8%). Conversely, the APC was inversely proportional, being higher for WS and lower for CS. HMT slightly modified the AC and APC differently in each botanical source. For example, RSS increased AC in the treatments with 10% and 30% moisture (0.9% and 0.6%, respectively) compared to native RSS, while CS only showed a reduction in HMT at 10% moisture (0.7%). The AC in WS increased as the moisture content of the treatment increased (1.1%, 2.2%, and 3.0%, with 10%, 20% and 30% moisture, respectively) compared with native starch.

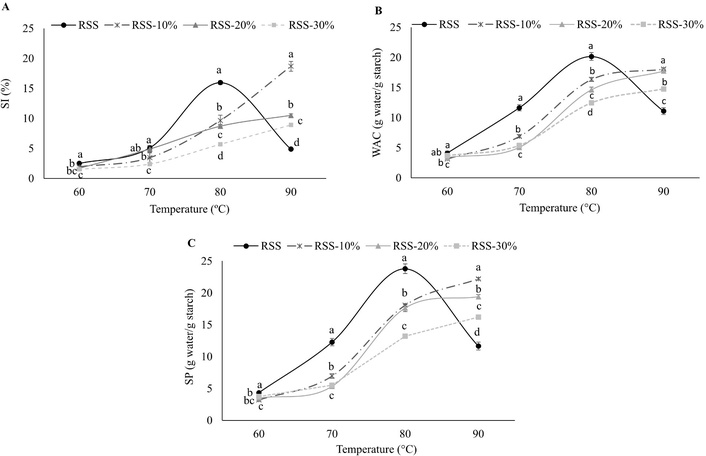

The results of functional properties (SI, WAC, and SP) of native and modified starches are shown in Table 3. The SI in native starches increased with the temperature, except for RSS at 90°C. RSS showed the lowest SI value at 60°C compared to WS and CS. At 70°C, no significant difference was observed; however, at 80°C, RSS had a significant increase over WS (7.8%) and CS (2.3%). At 90°C, while WS continued to increase, CS only had a slight increase, and RSS decreased drastically. The HMT modification of starches particularly favored RSS, which showed increased SI as the temperature increased up to 90°C, particularly in the HMT at 10% moisture from 80°C to 90°C, which was higher than WS and CS. However, at high moisture content (20% and 30%), this property decreased, being similar to CS and lower than WS at the highest temperature. SI in RSS native and modified by HMT is shown in Figure 2A. The HMT impacted RSS, modifying SI and showing a more stable behavior of starch granules as temperature increased.

Functional properties of native and HMT-modified starches.

| Starch | 60°C | 70°C | 80°C | 90°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI (%) | ||||

| RSS | 2.5 ± 0.1b | 5.1 ± 0.4a | 16.0 ± 0.3a | 4.9 ± 0.2c |

| CS | 4.8 ± 0.1a | 4.9 ± 0.1a | 13.7 ± 0.3b | 15.9 ± 0.4b |

| WS | 4.6 ± 0.2a | 4.6 ± 0.4a | 8.2 ± 0.2c | 22.2 ± 0.8a |

| RSS-10% | 1.9 ± 0.1c | 3.5 ± 0.8c | 9.7 ± 0.9a | 18.7 ± 0.8a |

| CS-10% | 4.8 ± 0.0a | 6.6 ± 0.4a | 8.3 ± 0.6b | 12.6 ± 1.6c |

| WS-10% | 3.5 ± 0.4b | 5.3 ± 0.3b | 6.1 ± 0.3c | 16.3 ± 0.1b |

| RSS-20% | 1.7 ± 0.1c | 4.2 ± 0.5b | 8.7 ± 0.3a | 10.5 ± 0.3c |

| CS-20% | 4.5 ± 0.2a | 6.0 ± 0.1a | 8.5 ± 0.3a | 11.3 ± 0.2b |

| WS-20% | 2.5 ± 0.4b | 3.9 ± 0.2b | 4.9 ± 0.3b | 16.6 ± 0.1a |

| RSS-30% | 1.5 ± 0.1c | 2.4 ± 0.2c | 5.7 ± 0.2b | 8.9 ± 0.2b |

| CS-30% | 3.4 ± 0.2a | 4.8 ± 0.1a | 7.6 ± 0.3a | 8.6 ± 0.0c |

| WS-30% | 2.2 ± 0.2b | 3.4 ± 0.3b | 4.9 ± 0.2c | 12.5 ± 0.2a |

| WAC (g water/g starch) | ||||

| RSS | 4.1 ± 0.3c | 11.6 ± 0.5b | 20.2 ± 0.6a | 11.1 ± 0.6c |

| CS | 8.0 ± 0.4b | 12.9 ± 0.3a | 14.4 ± 0.4b | 14.1 ± 0.1b |

| WS | 9.9 ± 0.3a | 12.2 ± 0.2ab | 11.1 ± 0.2c | 17.5 ± 0.5a |

| RSS-10% | 3.2 ± 0.2c | 6.9 ± 0.2c | 16.3 ± 0.3a | 18.1 ± 0.2a |

| CS-10% | 4.7 ± 0.4b | 9.4 ± 0.3b | 11.3 ± 0.2c | 12.8 ± 0.1c |

| WS-10% | 8.3 ± 0.2a | 10.6 ± 0.1a | 11.9 ± 0.2b | 13.3 ± 0.1b |

| RSS-20% | 3.4 ± 0.2c | 5.1 ± 0.1c | 14.6 ± 0.4a | 17.7 ± 0.3a |

| CS-20% | 6.4 ± 0.1b | 10.1 ± 0.2b | 10.5 ± 0.1c | 13.5 ± 0.4b |

| WS-20% | 9.6 ± 0.1a | 11.3 ± 0.4a | 12.3 ± 0.3b | 13.7 ± 0.4b |

| RSS-30% | 3.7 ± 0.1c | 5.4 ± 0.2c | 12.5 ± 0.2a | 14.8 ± 0.3a |

| CS-30% | 5.2 ± 0.3b | 9.0 ± 0.1b | 10.7 ± 0.3b | 12.6 ± 0.2c |

| WS-30% | 7.6 ± 0.2a | 11.1 ± 0.2a | 12.7 ± 0.3a | 13.4 ± 0.4b |

| SP (g water/g starch) | ||||

| RSS | 4.3 ± 0.2c | 12.3 ± 0.6b | 23.8 ± 0.8a | 11.6 ± 0.6c |

| CS | 8.4 ± 0.3b | 13.6 ± 0.3a | 16.8 ± 0.3b | 16.8 ± 0.1b |

| WS | 10.4 ± 0.3a | 12.8 ± 0.3ab | 12.1 ± 0.5c | 22.1 ± 0.0a |

| RSS-10% | 3.2 ± 0.2c | 7.0 ± 0.4c | 18.1 ± 0.2a | 22.2 ± 0.2a |

| CS-10% | 5.2 ± 0.1b | 10.2 ± 0.1b | 12.5 ± 0.4b | 14.6 ± 0.2c |

| WS-10% | 8.7 ± 0.2a | 11.2 ± 0.1a | 12.8 ± 0.2b | 16.0 ± 0.1b |

| RSS-20% | 3.5 ± 0.2c | 5.3 ± 0.1c | 17.6 ± 0.5a | 19.4 ± 0.4a |

| CS-20% | 6.7 ± 0.1b | 10.8 ± 0.2b | 11.5 ± 0.0c | 15.2 ± 0.4c |

| WS-20% | 9.9 ± 0.1a | 11.8 ± 0.4a | 12.9 ± 0.3b | 16.4 ± 0.5b |

| RSS-30% | 3.8 ± 0.1c | 5.5 ± 0.2c | 13.2 ± 0.2a | 16.2 ± 0.3a |

| CS-30% | 5.4 ± 0.4b | 9.5 ± 0.1b | 11.6 ± 0.4b | 13.7 ± 0.2c |

| WS-30% | 7.8 ± 0.3a | 11.5 ± 0.2a | 13.3 ± 0.3a | 15.4 ± 0.4b |

Mean values ± SD. SD = 0.0 indicate that SD < 0.01. SI: solubility index; WAC: water absorption capacity; SP: swelling power; RSS: Ramón seed starch; CS: corn starch; WS: wheat starch. 10%, 20% and 30% moisture in heat-moisture treatment (HMT) treatment. Comparisons among starches in the same treatment. Values in the same column with different lowercase letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Functional properties of native and HMT-modified RSS. (A) Solubility index (SI), (B) water absorption capacity (WAC), and (C) swelling power (SP). HMT: heat-moisture treatment; RSS: Ramón seed starch. Mean values ± SD. Comparisons among starches at the same temperature. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Similarly, RSS, native and modified by HMT, showed the lowest WAC values at lower temperatures. Significantly, this property increased at 80°C and 90°C only in RSS-modified by HMT, with the highest value observed in the treatment with 10% moisture (Table 3). RSS-modified by HMT showed higher WAC values than CS and WS (10% and 20% moisture) at the highest temperatures. The HTM improved the WAC of RSS, making it more stable to the starch granule in this property as the temperature increased, particularly the treatments with 10% and 20% moisture compared to its native counterpart (Figure 2B). The SP of the starch granule had a similar behavior to WAC (Table 3), where RSS in native form showed the highest SP at 80°C compared to WS and CS; however, RSS modified by HMT increased this property above WS and CS as the temperature and moisture content of the treatment increased. The highest SP of RSS-modified by HTM was observed at 10% and 20% moisture (Figure 2C), but this value was reduced at 30% moisture. Again, the modification of RSS by HMT treatment positively affected the starch granule, making the swelling more gradual and stable at higher temperatures.

It has been reported that RSF presents a high mineral content (3.4 g/100 g of flour) [10, 30], which is slightly lower than the value found in this study (3.7 g/100 g fresh weight). The main minerals reported were copper (0.5 mg/100 g), zinc (1.0 mg/100 g), iron (4.0 mg/100 g), potassium (1,256 mg/100 g), sodium (47 mg/100 g), and calcium (190 mg/100 g) [11, 14]. The RSF is obtained by drying in the sun, removing the seed coat, and grinding until a fine flour is obtained [31], without any mineral fortification. The mineral content of the Ramón’s seed may be due to the type of soil in which the tree grows. Brosimum alicastrum Sw. grows in sites of a limestone nature, with rapid drainage and steep slopes [32]. On the other hand, RSF showed slightly lower total protein content (13.1 ± 0.3 g/100 g flour) than WF. The RSF protein fraction is composed of 59% albumins, 25% globulins, 14% glutelins, and 1% prolamins; these types of proteins are storage proteins that can serve as an alternative for the preparation of gluten-free foods [33]. In total fat, RSF showed the lowest content compared to WF and CF. In a study carried out by Subiria-Cueto et al. [10] a fat content of 0.6% was reported for the Ramón flour obtained with a seed from Yucatán state, being lower than the fat content obtained in this study (1.2%, FW), whose seed was collected in Quintana Roo state, and lower than that reported by Carter [11] (2.02%) in flour obtained from seeds collected in the Veracruz state. The differences in the crude fat content may be due to the growing conditions, the geographical location, and the characteristics of the place, such as the type of soil, the availability of nutrients, and the climate, which can be understood by the ability of the Ramón tree to adapt to humid and arid climates, as well as its ability to take advantage of moisture and store it in the roots [34]. The crude fat content in WF and CF is similar to that reported by FAO for WF (1.3%) and corn (3.8%) [35]. The total carbohydrate content values obtained for RSF (74.3%) and WF (73.1%) in fresh weight (FW) are similar to results reported by Subiria-Cueto et al. [10] (71.2% and 76.3%, respectively). CF presented higher carbohydrate content (76.8% FW) compared to RSF, and similar to the value reported by Miranda Calero et al. [36] of 75%. The total carbohydrate fraction includes TS content, dietary fiber, and sugars. The RSF of this study also showed a slightly lower content than that reported in seeds from Guatemala (85.12%) and Nicaragua (83.61%) [11]. In dietary fiber content, the same study carried out by Carter [11] showed that the TDF of Ramón seeds from different countries (Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala) was in a range of 4.9% to 21.7% dry weight (DW), and the value obtained in this study was slightly highest. Still, it is higher than that reported by Subiria-Cueto et al. [10] (13.0% FW) in flour obtained with Ramón seed from Yucatán. This difference in TDF may be due to the area of origin of the seed, since the seed in this study was collected in Quintana Roo, where there was an unusual rainy season according to the RSF provider’s reference. The analysis carried out on WF (Selecta®) showed a TDF content (3.2% FW) similar to that reported on the product nutritional information (3.0%), and CF (Maseca®) had a higher content (10.4% FW) than reported in nutrition facts (7.0%). The low content of TDF in WF and CF compared to RSF may be due to the previous processing treatments, such as the reduction in particle size during grinding and screening, hulling, nixtamalization (CF), and refinement of both, before their commercialization, which represents a significant loss of the fiber present in cereals [37]. On the other hand, RSF involves an artisanal process that includes only sun drying, grinding, and more heterogeneous sieving without refining stages [6], which would explain a higher TDF content in RSF.

The yield of starch extracted from Ramón flour (RSS) was very similar to the starch obtained by Pech-Cohuo et al. [38] in Ramón seed (30.0%) and higher than the starch obtained from other seeds such as mango (Mangifera indica) (24.6%) [39] or avocado (Persea americana mill) (19.5%) [40] and even than CS. The Ramón seed can be considered a source of starch (30% minimum) [41]. The yield of different starches may depend on the botanical source and the extraction technique used for each starch [42]. The proximal composition of the starches studied (Table 1) was similar to that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] in RSS and CS. In moisture, the starches presented values less than 10%, which is optimal since only values less than 20% are allowed in starch as a raw material [43]. The moisture content of RSS was higher than reported by Dios-Avila et al. [44] for avocado seed starch (6.4%). The mineral content was low in all samples; however, RSS had the highest compared to that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] for RSS (0.47%) and Martins et al. [40] for avocado seed starch (0.33%), but lowest compared to that of mango seed starch (1.42%) [39]. The mineral content in CS was similar to that obtained by González-Soto et al. [45] (0.51%). The high ash content in RSS may be due to the type of soil in which the Ramón tree grows. Pietrzyk et al. [46] concluded that mineral compounds incorporated depend on the botanical origin of the starch and the type of mineral element added; therefore, when growing in shallow and stony soils, there is greater susceptibility to increasing the mineral content in Ramón seeds. In protein content, RSS (0.2%) presented a value slightly higher than that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] in Ramón starch (0.12%) and a very similar value compared to CS (0.10%). This low protein content in RSS is optimal for producing syrups with high glucose content, as it falls below the 0.4% protein percentage established by the FDA for CS [47]. WS showed higher protein content compared with RSS and CS, which may be due to the presence of gluten, which develops a thick, viscoelastic network that traps starch granules [48]. The RSS (0.40%) and CS (0.39%) crude fat content was slightly below that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] and similar to the value reported by Hernández-Medina et al. [47] for the CS (0.35%). The presence of lipids in starches may be due to the interactions that may exist between starch-lipid complexes, which are regulated by non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, Van der Waals forces, etc.). Amylose is the starch component that interacts with lipid molecules [49]. In total carbohydrate content, RSS showed a higher value than WS and CS. The total carbohydrate content of RSS is very similar to that of starches such as cassava, sago, and sweet potato (98.4%, 98.7%, and 98.9%, respectively) [47]. The TDF determined in RSS was 10.2% FW, much higher than that reported of 1.3% in a previous study carried out by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4]. These differences can be attributed in part to the grinding process of the seeds, since the more the cell wall is integrated, the higher the dietary fiber content in the starch [50, 51]. In addition, other factors such as the geographical location of seed collection, the harvest season, and the genetic variety, among others, may explain these differences [37]. The TDF content in RSS was higher than that of other starches, such as cassava (6.4%) or potato (4.8%) [52]. The starch-fiber complex forms a physical barrier through non-covalent bonds, such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic attractions. This complex generates a framework and overlaps between the molecular chains, which influences the gelatinization process of starch, forming an ordered and dense gel network [51].

The size of starch granules varies widely depending on their botanical source (< 1 to > 100 µm) [53]. The diameter of native Ramón starch granules (6.0–11 µm) and those modified by HMT (7.0–16.0 µm) was close to the range previously reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [15] for starch from Ramón seeds collected in Campeche (6.5–15.0 µm), Mexico. Also, the size of Ramón starch granules, native and modified by HMT, is similar to that of other starch granules from seeds such as sorghum (11.8–24.4 µm) and mango (1.0–13.0 µm) [42] or other sources such as oat, rice, buckwheat, tapioca, or barley (2.0–10.0 µm) [53]. Starch granule size can vary depending on the genotype and environmental conditions during plant growth [54], and this characteristic is an essential factor in the physicochemical and functional properties of starches. Small starch granules have been related to some applications in the food industry and non-food industries [55]. Currently, starches with small granules, such as oat, rice, and tapioca, are used as thickeners (custards, sauces, soups, gravies, and puddings), gluten-free ingredients, and fat replacers and creaming agents. Also, these starches are used in the pharmaceutical industry (coating agents and liquid medicines), cosmetics (makeup powders, toothpaste, creams, face masks, soaps, and lotions), construction (adhesives, polyurethanes, resins), packaging materials, and photographic paper, among others [56–58]. The diversity of uses for this type of starch with small granules could represent potential applications for RSS modified by HMT.

Considering the average value between the minimum and maximum mean diameters (Table 2), a percentage of increase or decrease in the starch granule size was calculated in relation to the native starch granule average value. The modification of Ramón starch with HMT resulted in a slight increase in the starch granule size, with the following trend: RSS-HMT10% > RSS-HMT20% > RSS-HMT30%. The increase was also observed in the WS granules in WS-HMT10% and WS-HMT30%. Interestingly, CS showed a reduction in the starch granule size in HMT (CS-HMT30% > CS-HMT20% > CS-HMT10%). This behavior, where small increases in granule size occur due to HMT modification, has also been observed in potato starch [59]. However, the impact of HMT may vary in different starches depending on their botanical origin. For example, it has been reported that tuber starches are more sensitive to HMT than legume or cereal starches [60]. The sensitivity of some starches may be attributed to the greater ease of agglomeration in the granule under the influence of moisture and heating during the treatment [61]. However, in the HMT of RSS with a 30% moisture content, the increase of starch granule size was lowest compared with HMT at 10 and 20% moisture. This effect was also observed in sand rice starch modified by HMT, which may be because a moisture content > 25% increases the hydration of the granule, destroying its morphology and causing partial gelatinization of the starch [62]. On the other hand, CS presented a reduction in the size of the starch granules. A similar effect was observed in sweet potato starch treated at higher moisture content. The effect was related to the evaporation of water molecules during the treatment and the formation of a more compact structure due to the rearrangement of the amylopectin double helices, indicating that the botanical source of starch plays a critical role in the modification by HMT [22, 63]. Finally, the shape observed in RSS granules is similar to that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4]. The HMT did not affect the shape, similar to that reported in oat starch granules [64] or other starch granules studied from cereal, legumes, and tubers [65].

According to Seung [66], starches commonly contain between 5% and 35% amylose in seeds and storage organs, and this proportion can vary between species and organs. In this study, the starches had an AC within this typical range. The AC of native RSS was slightly lower (0.4%) than that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4], with an amylose:amylopectin ratio very similar (1:2.94). In comparison, CS had the highest AC (0.7%) in this study, but with a ratio equal to that reported [4]. In WS, the AC observed was higher than that reported by Xing et al. [67]. The AC in starch granules can have a significant impact on the physical and chemical properties of starch, including gelatinization, viscoelasticity, gel hardness, swelling power, and digestibility, among others [68, 69]. However, in addition to the botanical source, other factors can influence variations in AC and APC, such as plants’ growing conditions, soil temperature, and climate, among others [69], which could explain the differences between the RSS and the other starches analyzed. However, all starches are found in the amylose:amylopectin ratio suggested for regular starches (1:4) [70], which places RSS as a non-conventional source of starch with various potential applications in food and non-food industry, replacing partially or totally conventional starches such as corn or wheat.

On the other hand, HMT has a different effect on AC in starches, which varies, increasing, reducing, or not changing the AC [71]. In the present study, RSS, CS, and WS showed a discrete increase in AC across different HMT treatments, while RSS and CS decreased in HMT10% and HMT20%, respectively. HMT induces changes to alter the crystalline structure of the starch granule and dissociate the double helix in the amorphous region, which causes the reorganization of the polymer chains. The magnitude of these changes can vary depending on the temperature, time, and moisture levels used in the treatment, among other factors [60]. An increase in AC has been observed in other starches treated by HMT, such as rice [72] and tapioca, possibly due to the heat treatment causing degradation in the external amylopectin chains, becoming semi-linear chains like amylose and forming complexes with other amylose chains, which could be responsible for this increase [73]. In the case of a decrease, this effect could be due to the formation of starch-lipid complexes during treatment with heat-moisture [71], which is consistent with the high lipid content that CS presented, or starch-dietary fiber complexes [49], which is consistent with the high TDF content of RSS.

The low native RSS values in SI at 60°C are similar to those reported for other starches such as avocado seed (2.2%) [74], potato (2.5%), rice (3.3%) [75] or Mysore banana (2.5%) [76], as well as the tendency to increase slightly at 70°C, and higher than that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] for RSS at the same temperatures (0% and 2.0%), however this RSS behavior at low temperatures may be helpful in specific applications such as crunchy foods with reduced water and fat content [76] as snacks. The RSS behavior is consistent with that observed for WAC and SP, where this native starch showed its maximum point in these functional properties at 80°C and above, compared to conventional starches such as wheat and corn. In this study, RSS had approximately twice the values in SI, WAC, and SP than those reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] at same temperature, the RRS starch granules may reach the maximum point of hydration (swelling or gelatinization), in which a rupture of intermolecular forces of the amorphous areas occurs, facilitating the absorption of water progressively and irreversibly [4, 74]. This RSS behavior is consistent with the gelatinization temperatures of RSS reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4], which starts at 75.0 ± 1.0°C (To) and reaches the maximum peak (Tp) at 83.0 ± 0.5°C, being significantly superior to CS and WS in all functional properties. The hydration and swelling capacity of starch granules at high temperatures depends on their ability to break the hydrogen bonds that stabilize the double helix structure formed by the amylose and amylopectin chains and replace them with water. This process increases the leaching and solubility of amylose due to the loss of the crystalline structure. Factors such as the botanical source, granule size, and holes and channels within the starch granule can influence this characteristic. Small starch granules have shown greater SP [44, 77]. In this study, RSS had smaller starch granules than CS and WS, which could influence this behavior. However, the RSS behavior changed at 90°C, drastically reducing the granule properties in SI, WAC, and SP and falling below those of CS and WS. This data is contrary to that reported by Pérez-Pacheco et al. [4] for RSS for solubility (~20%), water absorption (~13 g water/g starch), and SP (17.6 g water/g starch). However, this effect has been observed in other starches such as potato, tapioca, and waxy corn, showing a maximum SP at 80°C and decreasing towards 85°C and 95°C, showing that SP increased when Tp (70–80°C) was reached [78]. Also, Mysore banana starch showed a drop in solubility after 70°C, possibly due to starch granule disruption and leaching of compounds [76].

On the other hand, RSS modified by HMT improved the behavior of starch granules in SI, WAC, and SP by slightly reducing these properties at 80°C but increasing them at 90°C. At the same time, CS and WS decreased the properties in the two highest temperatures compared to native starches. Different effects of HMT on starch have been reported, causing changes such as an increase in the initial gelatinization temperature, modification of X-ray diffraction patterns, granule morphology, thermal properties, swelling power, solubility, and enzyme digestibility, among others [79]. Studies on different starches have reported that this effect may be due to HMT causing changes in the thermodynamically less stable β-polymorphic structure of the double helices towards a more stable monoclinic structure, which results in less water trapped in the same [60], causing a rearrangement of the amylose and amylopectin molecules that provoke the loss of free hydroxyl groups, which reduces the solubility of the granule [80]. These changes could explain the reduction in functional properties at 70°C and 80°C of HMT-modified RSS compared to native starch. This effect has also been observed in waxy potato, corn, and chickpea starches, where the modified starches reduced the solubility and swelling power compared to their native counterpart, which was attributed to factors such as structural weakening due to the breakdown of the double helix in the HMT. During heating in the HMT, a change may occur in the amorphous region that causes greater rigidity of the granular structure of the starch, disrupting its crystalline structure [80, 81]. Finally, the water content in the HMT caused, in all starches, a reduction in SI, WAC, and SP at the different temperatures. HMT with 10% moisture was where RSS showed the highest SI, WAC, and SP values at 90°C compared to CS-10% and WS-10%, and the HMT-modified starches at 20% and 30% moisture. Sui et al. [82] observed this behavior in maize starch modified by the HMT method at 20%, 25% and 30% moisture, where swelling power was reduced as the moisture content of the treatment increased, which may be due to the interaction of the starch components in the amorphous zone during the treatment, increasing the interactions between the amylose chains, generating the conversion of amorphous amylose into helical amylose [22, 80]. This molecular rearrangement can explain this behavior in RSS modified by HMT. Further studies on the granule structure and structure of native and modified RSS are necessary for a better understanding of the behavior of this starch.

RSF is a source of starch (RSS), whose granules are significantly smaller than CS and WS. The AC in RSS is slightly lower than that of CS and similar to that of WS. The RSS modified by HMT slightly increased granule size but preserved its shape and AC. However, HMT-modified RSS significantly improved its functional properties, such as SI, WAC, and SP, showing a more gradual, controlled, and stable behavior at high temperatures. Notably, HMT 10% moisture showed values higher in these properties than CS and WS. Therefore, HMT-modified RSS at 10% moisture possesses functional properties that could be attractive for use in the industry. However, studies on the thermal, structural, and rheological properties are necessary to establish the potential and better applications of RSS modified by HMT.

AC: amylose content

APC: amylopectin content

CF: corn flour

Con-A: Concanavalin A

CS: corn starch

FW: fresh weight

HMT: heat-moisture treatment

RSF: Ramón seed flour

RSS: Ramón seed starch

SI: solubility index

SP: swelling power

TDF: total dietary fiber

WAC: water absorption capacity

WF: wheat flour

WS: wheat starch

The authors thank Hortensia Reyes Blas, PhD, for the technical support in electron microscopy in this study and Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) for funding Perla A. Magallanes Cruz´s postdoctoral fellowship (I1200/224/2021) in Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico.

PAMC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LAQC: Methodology, Investigation. IOA: Methodology, Investigation, Resources. EAP: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. NRMR: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Data and materials are available on request from the authors.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1227

Download: 99

Times Cited: 0

Joseph A. Adeyemi ... Fernando Barbosa