Affiliation:

Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606, USA

Email: ron.viola@utoledo.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3117-9168

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008147 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008147

Received: December 01, 2025 Accepted: January 12, 2026 Published: February 01, 2026

Academic Editor: Francisco Javier Luque Garriga, University of Barcelona, Spain

The article belongs to the special issue The Rise of Targeted Covalent Inhibitors in Drug Discovery

Over the past several decades there has been a growing recognition of the role that covalent drug candidates have played in the drug development process. With this recognition, compounds that are capable of selectively and irreversibly inactivating their targets through covalent bond formation are now being specifically designed rather than being serendipitously identified. Until recently, vinyl sulfones comprised only a small fraction of the warheads under development as covalent drug candidates, but an increasing number of compounds containing this versatile functional group are now under development and consideration as drug candidates. Vinyl sulfones are generally more reactive than structurally-related acrylamides and vinyl sulfonamides, presenting a challenge for producing target-specific inactivators. The most progress in overcoming this challenge has been made in designing vinyl sulfones as selective inactivators of microbial and human cysteine proteases, incorporating these reactive warheads into peptide and peptide mimetic structures that utilize the substrate recognition motifs of these proteases. However, effective vinyl sulfones have also been produced against a growing range of phosphoryl-utilizing enzymes including kinases, phosphatases and metabolic enzymes. Here, target selection takes advantage of the capability of the sulfonyl group to act as a phosphoryl mimic. An example of this approach is presented for the targeting of a metabolic enzyme, fungal aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, an essential microbial enzyme in amino acid metabolism. The studies conducted to date demonstrate the potential utility of designing vinyl sulfone drug candidates to achieve selectivity against challenging and new drug-resistant targets.

The vast majority of the drugs that have been introduced into clinical use were not designed to function as irreversible inactivators of their targets. Yet about 30% of the drugs that target enzymes, including classical drugs such as aspirin and penicillin, were subsequently found to function by covalently modifying their target enzyme [1]. Despite the inherent advantages of covalent drugs, including higher target affinity and longer duration of action when compared to traditional reversible drugs, concerns over the lack of target selectivity have limited the number of new drugs that function by covalent inactivation of their target to less than 5% of FDA-approved drugs over the past decade [2]. Unfortunately, there is still an existing prejudice that covalent inactivators are unlikely to possess desirable drug-like properties, in particular concerns over their perceived lack of selectivity due to high inherent reactivity. To overcome this perception barrier, new classes of enzyme inactivators are being developed that demonstrate the potential to effectively and selectively modify a wide range of validated drug targets.

Vinyl sulfones, the class of covalent inactivators that are the focus of this review, already possess inherent selectivity for certain classes of targets that can be further enhanced through structure-guided optimization. Several articles have reviewed the recent advances in the use of vinyl sulfones as covalent drug candidates [3–5], and numerous reviews have examined the different routes that are available to synthesize vinyl sulfones [3, 6–8]. This work focuses primarily on the reactions of different vinyl sulfones with specific protein targets. The presence of a sulfonyl group with similar size, charge distribution, and hydrogen-bond acceptor potential predisposes this class of compounds for selective binding to enzymes that utilize phosphoryl-containing substrates. Subsequent incorporation of complementary binding groups can enhance this selectivity, thereby positioning the activated vinyl group in optimal proximity to the enzyme nucleophile for enhanced on-target reactivity. Combining these approaches, with the potential therapeutic selectivity that can be achieved by the judicious selection of microbial targets that are absent in the mammalian world, can lead to an improved class of covalent antimicrobial agents. Furthermore, the irreversible mode of action of these new agents will circumvent most of the known drug resistance mechanisms that are rendering the current antimicrobial drugs increasingly ineffective.

Active compounds that are designed to function as selective, irreversible inactivators of their targets are composed of a reactive functional group (the warhead) and a recognition motif that directs the warhead to a key binding site on its target. To date, α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds have been the most widely used warheads in the design of covalent inactivators. However, a wider range of reactive functional groups, including activated esters, lactams, lactones, epoxides, boronates, and aziridines, have also been incorporated into successful covalent inactivators. Sulfur-containing functional groups, including α, β-unsaturated sulfones and sulfonamides, have also begun to make significant contributions to the covalent drug development pipeline.

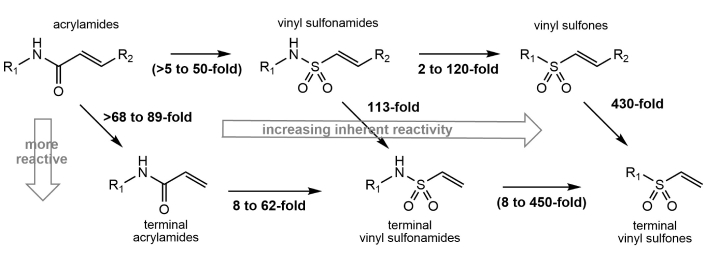

For the classes of inactivators that utilize an activated vinyl group as their reactive warhead, numerous studies have examined their relative reaction rates with model thiol nucleophiles such as glutathione or cysteine. A quantitative comparison of the reactivity of terminal and internal acrylamides, vinyl sulfonamides, and vinyl sulfones is difficult because of differences in the reaction conditions and in the identities of the R groups used among the various studies. Shown are some representative examples of the relative half-lives of closely related structures in the presence of low molecular weight thiol nucleophiles (Figure 1). For these kinetic comparisons, R1 is either a methyl or a phenyl group, and the R2 groups are the same (or as close as possible) for each pairwise comparison. Based on these examples, terminal acrylamides are at least 68-fold more reactive than internal acrylamides [9, 10]; terminal vinyl sulfonamides are greater than 100-fold more reactive than internal ones [10]; and terminal vinyl sulfones are greater than 400-fold more reactive than internal vinyl sulfones [11]. This higher reactivity of terminal electrophiles increases the likelihood of modifying multiple targets within the cell, leading to potentially deleterious side effects. Therefore, the incorporation of various R groups positioned α to the vinyl group in these structures serves not only to improve their selectivity by providing target recognition groups, but also functions to modulate the high compound reactivity that could result in increased promiscuity. In general, vinyl sulfones are more reactive towards thiol nucleophiles when compared to acrylamides and vinyl sulfonamides [10, 12] (Figure 1), and therefore can function as highly efficient covalent inactivators if this warhead can be properly directed towards their proposed targets.

Relative reactivity of different classes of α, β-unsaturated reactive groups against thiol nucleophiles. Terminal vinyl groups are significantly more reactive than substituted functional groups. Vinyl sulfones are generally more reactive than vinyl sulfonamides and acrylamides. The values shown in parentheses were calculated from the measured values of structurally related compounds. Modified from [13]. © 2025 The Author(s). CC BY.

This comparison of the relative reactivity of different warheads examined pairs of compounds with neutral R groups. Within each class of vinyl-containing warheads, the presence of more electron-withdrawing R groups would cause an increase in compound reactivity by making this electrophile more susceptible to attack by thiol nucleophiles. For example, replacing the methyl group at R1 with a trifluoromethyl group results in an 8-fold increase in the rate of inactivation of a fungal metabolic enzyme by structurally related vinyl sulfones [14].

Reactivity, or the lack of reactivity, towards low molecular weight thiols such as cysteine or glutathione has traditionally been used to measure the selectivity and the irreversibility of covalent reagents designed against specific targets [15–17]. While the inherent reactivity of different activated vinyl groups is an important component in assessing compound efficacy, several additional factors, such as binding specificity and the microenvironment of the protein nucleophile, also play significant roles in target selectivity. For example, terminal sulfonamides are from 8- to 62-fold more reactive than terminal acrylamides against low molecular weight thiols (Figure 1). However, phenyl sulfonamide was observed to be 440-fold more effective than phenyl acrylamide at modifying the active site cysteine of papain [18], with this additional 7- to 55-fold enhanced selectivity a consequence of the higher binding preference of papain for the sulfonamide functional group over an acrylamide.

In order to better predict target selectivity, more challenging selectivity tests have been developed in which reaction rates have been compared between other thiol-containing proteins and the expected target. One such test examined reagent reactivity with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme with a thiol-dependent catalytic mechanism [19]. A related test used mass spectroscopic analysis of serum albumin covalent modification as a measure of target selectivity [20]. As expected, these studies confirmed the lack of selectivity of some simple, more highly reactive terminal vinyl sulfones and suggested that benchmarking new reagent selectivity against other proteins will provide a more stringent evaluation of vinyl sulfone selectivity than comparisons against low molecular weight thiols [20].

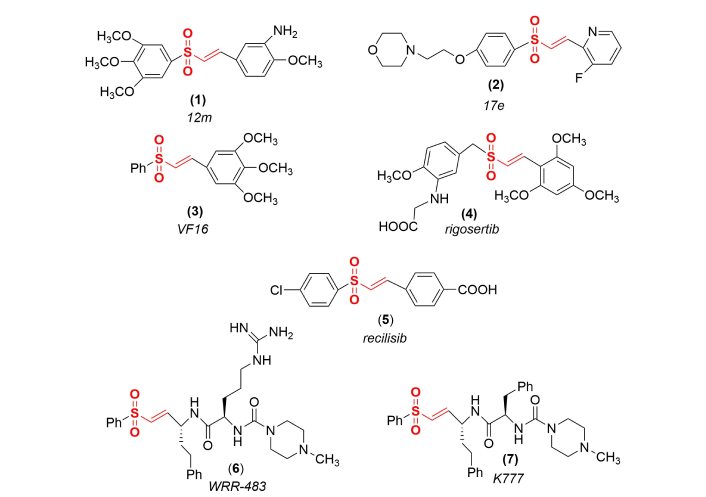

While not as prevalent as other classes of covalent inactivators, numerous vinyl sulfones have been introduced into the drug pipeline and several of these compounds with clearly identified targets and potential disease treatments have been refined as more advanced drug candidates. Some prominent examples (Figure 2) include compound 12m (1), an antitumor agent that functions as a tubulin polymerization inhibitor [21], compound 17e (2) that targets nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2) as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease [22], and compound VF16 (3) that targets the ATP-binding site of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase with potent anticancer activity [23]. Rigosertib (4) has been proposed to function as a microtubule-destabilizing agent for the treatment of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia [24], however, its mode of action and cellular targets remain controversial [25]. Recilisib (5) functions as a radioprotective agent through upregulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway in cells that have been exposed to acute radiation [26]. WRR-483 (6) [27] and K777 (7) were produced as antiviral agents that inhibit cathepsin K in the treatment of Chagas disease [28]. However, K777 has subsequently been found to also inhibit human cathepsin L, thereby blocking the required processing of the spike protein and preventing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) viral entry into cells [29].

Examples of some vinyl sulfone advanced drug candidates. These compounds are being examined as antitumor, anticancer, and antiviral agents, as well as for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, Chagas disease, and COVID.

As the superior selectivity and reactivity of vinyl sulfones have become more widely recognized, an increasing number of covalent inactivators of this class are being designed against new drug targets. Some examples of the enzymes being targeted by vinyl sulfones are described below. However, despite their desirable properties, to date, no vinyl sulfone covalent drugs have yet completed the journey through the drug development pipeline and moved into clinical use.

Cysteine proteases play central roles in all life forms, from parasites to mammals. In humans, cysteine proteases are involved in processes as diverse as cell development and signaling, inflammation, and immune responses. Identifying selective and species-specific inhibitors of cysteine proteases has been a challenge because these enzymes are so ubiquitous and share a common catalytic mechanism.

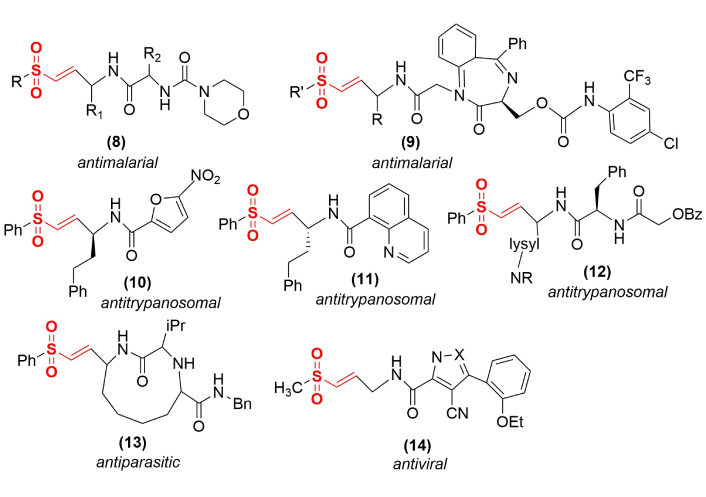

The use of irreversible inactivators, such as vinyl sulfones, can be used to address this challenge if specificity can be engineered into these drug candidates. The various approaches used to meet this challenge have relied on accessing the extended substrate recognition pocket of these proteases by designing peptidyl and peptidyl mimetic vinyl sulfones to match the known sequence selectivity of a particular protease target (Figure 3). In each case, the goal is to orient the vinyl electrophile into close proximity and ideal orientation relative to the active site cysteinyl nucleophile for subsequent reaction. There are many examples of cysteine protease vinyl sulfone inactivators that have been successfully designed to be highly target-selective. A particular set of antimalarial compounds includes dipeptides with N-terminal morpholino derivatives (8), where R1 = homophenylalanyl and R2 = leucyl, which is the most potent of this series [30]. A series of 1,4-benzodiazepine derivatives (9) also target falcipain, a Plasmodium falciparaum cysteine protease, to function as antimalarial agents [31]. Nitroaromatic heterocyclic derivatives (10) and quinoline derivatives (11) each function as antitrypanosomal agents by inactivating rhodesain, a cysteine protease in Trypanosoma brucei [32, 33]. A series of peptidomimetics (12) also function as antitrypanosomal agents, with the most effective of these compounds incorporating lysyl derivatives (where R = tosyl or sulfoxide) that show minimal toxicity against a human leukemia cell line [34]. More elaborate peptidyl mimetic structures have been designed that contain macrocyclic rings (13) [35], showing antiparasitic activity against the cysteine protease of Trypanosoma cruzi, and modified pyrazole (14, X=N) or oxazole (14, X=O) rings that show selective antiviral activity against the Chikungunya nsP2 cysteine protease [36]. Numerous other examples of vinyl sulfones are currently in development against specific cysteine proteinases.

Representative peptidyl and peptidyl mimetic vinyl sulfone inactivators of microbial cysteine proteases. Incorporating specificity towards particular cysteine protease targets has produced antiparasitic, antitrypanosomal, antimalarial, and antiviral agents.

Vinyl sulfones are excellent phosphoryl mimetics (Figure 1), with the sulfonyl group having very similar central atom to oxygen bond lengths, similar charge on the central atom, and nearly identical negative charges on the peripheral oxygens [37]; properties that would support the sulfonyl oxygen’s participation as excellent hydrogen bond acceptors when bound within a phosphoryl binding site. These properties predispose both high affinity and excellent selectivity for vinyl sulfones towards diverse families of phosphoryl-utilizing enzymes as potential drug targets. Many enzymes previously identified as drug development targets for a range of different therapeutic treatments utilize phosphoryl-containing substrates, more accurately called a phosphonato group. These different enzyme classes function by catalyzing the introduction of a phosphoryl group (kinases), the transfer of a phosphoryl group (phosphomutases), or the removal of a phosphoryl group (phosphatases). Many of these transfers involve the introduction or removal of a protein phosphoryl group as a control mechanism in signaling pathways. Here, the major challenge is to design drugs that achieve selectivity among the myriad protein kinases and protein phosphatases that utilize the same phosphoryl donor and similar amino acid side chains as phosphoryl acceptors. There are also important substrate activations via phosphorylation, catalyzed by various metabolic enzymes. A number of these enzymes catalyze key reactions in essential microbial pathways and have been identified as potential antimicrobial targets.

The phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of tyrosyl residues in a wide range of proteins, catalyzed by specific protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), plays a key role in the regulation of both normal and pathological processes. The capability of vinyl sulfones to serve as phosphoryl mimetics provides an opportunity to develop an entirely new class of covalent drugs that could have an impact on human diseases, ranging from cancer, diabetes, and obesity to autoimmune diseases. Unfortunately, only a few inroads have been made into this potentially rewarding field to date, limited primarily by the unmet challenge of building specificity into PTK and PTP inactivators.

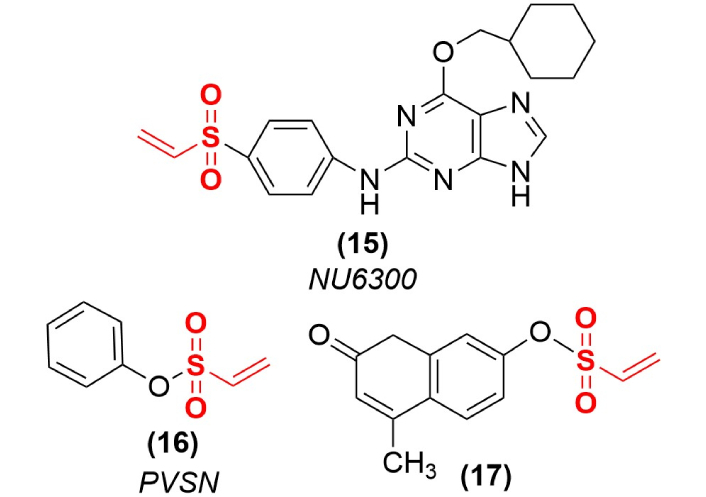

The vast majority of PTK inhibitors function as reversible, competitive inhibitors of ATP, however, a few covalent inactivators have been designed to access this binding site. The vinyl sulfone functional group was attached to a series of adenosine derivatives to target this reactive moiety to the ATP binding site of PTKs. The irreversible inactivation of a cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) through covalent modification of an active site lysyl residue, with compound NU6300 (15) as one example (Figure 4), demonstrates the efficacy of this approach [38]. Some simple aryl vinyl sulfones (Figure 4) have also been examined as mechanism-based PTP inactivators (16), however, their high reactivity typically comes at the expense of target selectivity. Some vinyl sulfones on bulkier scaffolds (17) were found to be potent PTP inactivators with excellent cell permeability. These reactive terminal vinyl sulfones tend to function as broad spectrum PTP inactivators, but still show several hundred-fold selectivity against PTPs as compared to their reactivity against cysteine proteases [39]. The structure of an inactivated PTP shows the expected S-C covalent bond formed between the active site cysteine nucleophile (C403) and the phenyl vinyl sulfone (PVS) inactivator [39]. However, as expected, these reactive compounds were not particularly selective among the classes of PTPs, with multiple target labeling observed [40], and more than one adduct incorporated among the PTPs that were examined by mass spectrometry [41].

Terminal vinyl sulfones that function as PTK or PTP inactivators. An adenosyl derivative (15) was designed to target the ATP site of PTKs, while some simple terminal vinyl sulfones (16, 17) are potent PTP inactivators. PTK: protein tyrosine kinase; PTP: protein tyrosine phosphatase.

Achieving target selectivity among the large family of PTKs and PTPs is more challenging than achieving cysteine protease selectivity, where the differences in protein targets combined with an extended substrate binding site can be used to incorporate a reactive functional group into a specific peptide sequence to target a particular cysteine protease of interest. Specificity among PTKs and PTPs is primarily driven by the recognition of a specific tyrosine/phosphotyrosine residue in its immediate environment within a substrate protein. In these cases, more detailed structural information is needed to learn how different PTKs/PTPs distinguish among the large number of potential protein targets. Once these details are obtained, one suggestion is to design bifunctional reagents with specificity determinants that recognize the non-conserved surface amino acids that are responsible for the protein-protein interactions needed for substrate recognition [42]. These selective interactions could then be used to deliver the reactive vinyl sulfone warhead to a specific target. A vinyl sulfone could also be incorporated into a complementary peptide recognition sequence, similar to the approach that has been used successfully for cysteine protease targeting.

While fungal infections are not typically associated with pandemic-level outbreaks, such diseases are still among the leading causes of human mortality [43], particularly among immunocompromised patients [44]. Treating systemic infections arising from pathogenic fungi is a difficult and challenging undertaking. The paucity of antifungal drugs is due primarily to the significant overlap of pathways between humans and fungi, resulting in much greater challenges in identifying unique fungal drug targets. The slim chances of success plummet even further when the infection occurs in an immunocompromised patient or if it is caused by a drug-resistant fungal strain. With the rapidly evolving capability of microorganisms to implement an array of defense mechanisms against drugs with a reversible mode of action, it is not surprising that fungal species have developed resistance to these few antifungal drugs.

Substrate-level phosphorylations are a critical component of cellular metabolism in all species, creating charged intermediates that cannot easily escape their metabolic fate and utilizing nucleotide triphosphates as phosphoryl donors to produce energetically favorable downstream reactions. Despite the metabolic similarities among eukaryotic organisms, there are some uniquely microbial metabolic pathways. The aspartate biosynthetic pathway is one such pathway, producing essential amino acid building blocks for protein synthesis and key metabolites that are critical for microbial survival [45]. This pathway has been validated as an important new target for anti-tuberculosis drug development [43], and several of the genes in this pathway are found among the minimal set of essential genes required for microbial survival [46, 47].

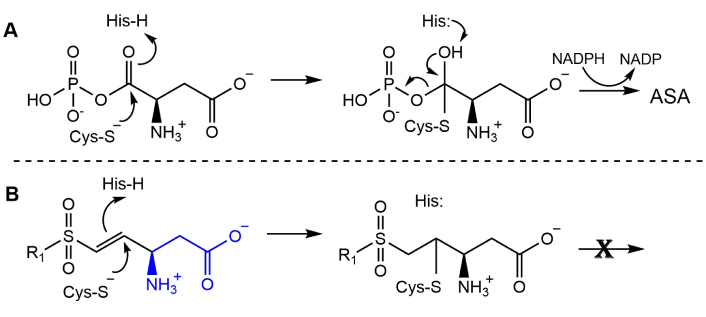

Enzymes have evolved the capability to identify unique structures from among the myriad collection of closely related cellular components, for selective binding and subsequent conversion to the necessary metabolites to insure cellular survival. Selection from among the set of enzymes that are essential for survival of pathogenic microbial species provides a group of potential targets for antimicrobial drug development. The best class of enzyme inhibitors, called active site-directed inhibitors, take advantage of this inherent selectivity by mimicking the substrate structure in their design criteria. This approach has been used to synthesize a set of vinyl sulfones [14], in which the sulfonyl group serves as a mimetic of the phosphoryl group of the aspartyl phosphate substrate of the essential microbial enzyme aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ASADH) (Figure 5). The catalytic cycle of ASADH starts by the nucleophilic attack of an active site cysteinyl group on the carbonyl of the substrate, followed by protonation by an active site histidine (Figure 5A) [48]. Reductive dephosphorylation leads to the aspartate semialdehyde (ASA) product that is the common intermediate for the subsequent steps in this essential pathway [49]. Initiating the catalytic cycle in the presence of an appropriately positioned vinyl sulfone allows the initial attack by cysteine; however, protonation of the enzyme adduct by an adjacent histidinyl residue results in the irreversible covalent modification of the active site cysteine of this enzyme (Figure 5B).

Reaction catalyzed by ASADH, and its irreversible inactivation by a vinyl sulfone. (A) ASADH mechanism, with the active site cysteine attacking aspartyl phosphate, followed by dephosphorylation and subsequent reduction to produce the key intermediate ASA. (B) Mechanism of irreversible inactivation of ASADH by vinyl sulfones, where variations in R1 are used to fine tune the inactivator efficiency, and a substrate mimic (blue) is shown in the R2 position. ASA: aspartate semialdehyde; ASADH: aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Reprinted from [13]. © 2025 The Author(s). CC BY.

A number of vinyl sulfones have been synthesized to identify and optimize active site-directed inactivators against this essential fungal enzyme [13, 14], with a small set of these inactivators shown in Table 1.

| R1 | R2 | Ki (µM) | kinact (min–1) | kinact/Ki (M–1 s–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl | 4-Pyridinyl | 5.69 | 0.24 | 690 |

| Methyl | 5-Nitrothiophene | 2.10 | 1.02 | 8,100 |

| Methyl | 2-Quinoline | 0.96 | 0.67 | 11,600 |

| Methyl | 5-Isoquinoline | 0.65 | 0.73 | 18,700 |

| Methyl | Alanyl | 7.6 | 0.25 | 550 |

| Benzyl | Alanyl | 1.8 | 0.27 | 3,000 |

| Isopropyl | Alanyl | 0.76 | 0.26 | 6,000 |

| Cyclopropyl | Alanyl | 0.39 | 0.31 | 13,000 |

These compounds each functioned as irreversible inactivators of the ASADH isolated from Candida albicans (C. albicans), a pathogenic fungal species. Changes in the identity of R2 result in higher affinity, increased inactivation rates, and improvements in the ratio of inactivation rate (kinact) to affinity (Ki) that serves as a measure of covalent inactivator efficiency (Table 1, top). Further increases in target affinity are observed with changes to R1 (Table 1, bottom). ASADH: aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase.

However, to serve as drug candidates, these inactivators must also be able to gain access to viable fungal cells and function as effective fungicidal agents. Several candidates from among these vinyl sulfones are now beginning to show good to excellent antifungal activity against native Candida albicans strains [13]. Further modifications of these vinyl sulfone inactivators are planned to enhance their efficacy against ASADH, with the goal of producing fungicidal agents that are effective against the increasing number of drug-resistant Candida strains.

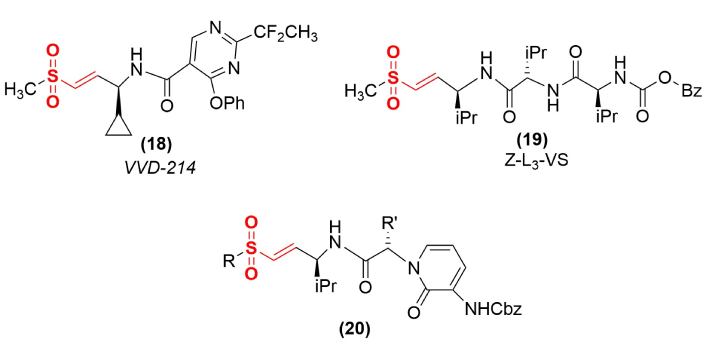

Vinyl sulfones have also been directed against cysteine residues located in allosteric sites to modulate enzyme activity (Figure 6). Compound VVD-214 (18) is an example of a recently synthesized allosteric inactivator that functions through the modification of a cysteinyl residue in an allosteric site [50]. This inactivation induces tumor regression in colorectal cancer models and is under evaluation against cancers that function through the disruption of DNA mismatch repair systems [50]. Cysteine residues are the most nucleophilic side chains in proteins; however, in some cases, the higher reactivity of vinyl sulfones relative to other covalent inactivators has been used to access other amino acids and other sites in enzymes (Figure 6). Producing an extended peptide chain vinyl sulfone with an improved match to the substrate binding site (19) helps to position the reactive electrophile into an optimal position to modify a less reactive nucleophile, such as the active site threonine in the peptidyl-glutamyl peptidase of a proteosome [51]. Defects in the proteosome pathway can lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor development. A series of conformationally-constrained tripeptides containing the vinyl sulfone warhead (20) was optimized to inactivate the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteosome pathway [52], where the most potent compounds of this series had R = methyl or ethyl and R′ = isopropyl or homophenylalanyl.

Altering the target of vinyl sulfone inactivation. Shown are examples of an allosteric inactivator (VVD-214), an inactivator that modifies an active site threonine residue (Z-L3-VS), and an inactivator (20) of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteosome pathway.

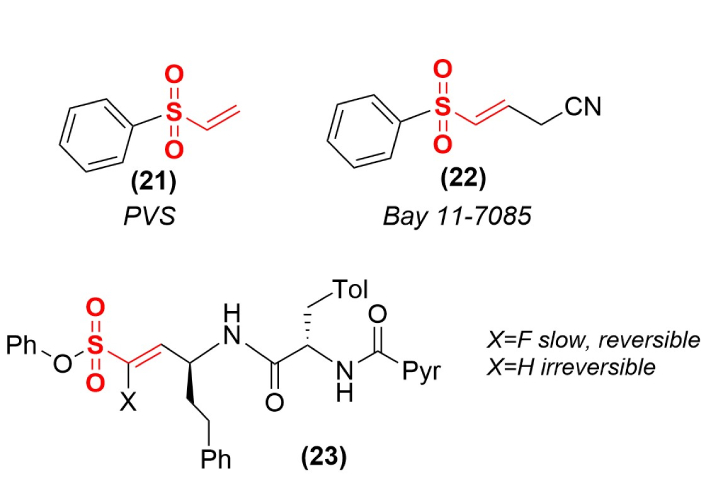

Terminal vinyl sulfones are significantly more reactive than the substituted functional moiety (Figure 1), and this enhanced reactivity has been used to produce general inactivators of PTPs (Figure 7) such as PVS (21). Modifications of this core structure have led to more selective and less reactive versions such as Bay 11-7085 (22) that act as a phosphotyrosine mimic to selectively inactivate protein arginine methyltransferase [53]. This enzyme can produce high levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine, a marker of kidney misfunction and cardiovascular disease.

Modification of vinyl sulfone reactivity and irreversibility. Replacement of the α-hydrogen (X) in compound 23 with a fluorine converts this irreversible inactivator into a slow binding but reversible enzyme inhibitor.

While vinyl sulfones typically function as irreversible inactivators of the enzyme targets, a simple substitution has the potential to convert these inactivators into tight binding, but reversible inhibitors. A substituted peptidyl vinyl sulfone (23) serves as a potent irreversible inactivator of the trypanosomal cysteine protease rhodesain. However, the replacement of the proton at the α-vinyl position with a fluorine (23, X=F) converts this compound into a slow, reversible inhibitor of this enzyme target [54]. Creating a more acidic proton at the adjacent position in the covalent enzyme adduct allows for the possibility of proton removal and the reversal of inactivation. In principle, the same approach could be used to convert other irreversible enzyme inactivators into slow, tight binding inhibitors to function in situations where a decrease in catalytic function leads to a more favorable outcome than its complete elimination.

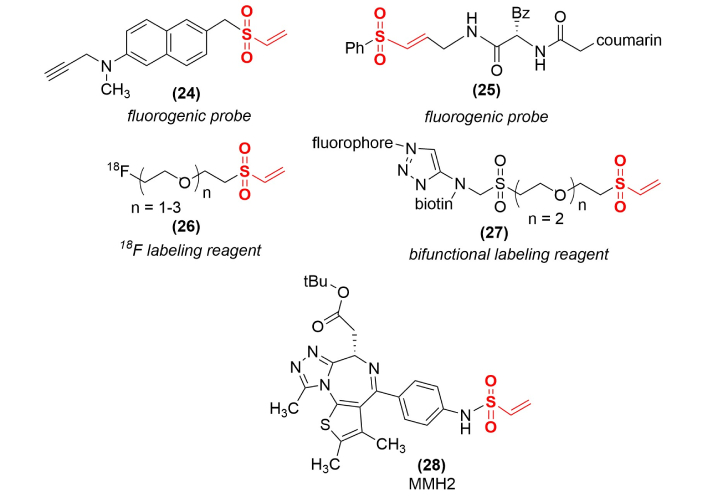

Controlling the reactivity of vinyl sulfones allows their use for the delivery of specific labels to protein sites that would be difficult to carry out by direct labeling. Several examples of this application (Figure 8) include the development of fluorogenic probes for the labeling of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (24), an enzyme that is upregulated in rapidly proliferating cancer cells [55], and a coumarin containing vinyl sulfone probe (25) for human cathepsin S labeling [56]. A reactive terminal vinyl sulfone (26) provided the covalent link for producing a general 18F-labeling reagent for positron emission tomography (PET) applications [57]. The same core structure was used to create a bifunctional labeling reagent (27) to covalently attach both biotin and a fluorophore to a single site on a protein [58], while a bifunctional reagent used a reactive vinyl sulfone in a peptide mimetic core to attach a coumarin fluorescent tag and a biotin at a single site [59]. A unique application in protein labeling involves a vinyl sulfonamide (MMH2, 28) functioning as a covalent molecular glue degrader to stabilize the protein-protein interface between a ubiquitin ligase and a specific protein substrate, resulting in enhanced proteosomal degradation of a difficult drug target [60].

Use of vinyl sulfones for selective covalent protein labeling. Examples shown include fluorescence labeling reagents, fluorine-18 (18F) labeling for PET scan applications, a bifunctional labeling reagent to introduce a fluorophore and a biotin tag at a single site, and a molecular glue degrader (MMH2). PET: positron emission tomography.

A growing recognition of the expanding role and unique features of covalent drugs has led to a resurgence in research to develop drug candidates that can harness the reactivity of covalent functional groups and direct them to difficult drug targets with high selectivity. The vinyl sulfone functional group is playing an increasing role in this field and has several advantages over the more traditional and broadly used covalent warheads. The presence of a phosphoryl mimetic provides a predisposition towards interactions with enzymes that utilize substrates containing this ubiquitous group. Vinyl sulfones are among the most reactive warheads, with reactivities that can then be modulated by the introduction of additional substrate recognition elements to convert them into less reactive internal functional groups and enhance their protein targeting. Numerous vinyl sulfones have already been shown to selectively inactivate different enzyme targets. Coupling the vinyl sulfone moiety to specific peptide and peptide mimetic sequences has enabled the selective targeting of key cysteine proteases as antimicrobial agents. Exploiting the capability of the sulfonyl group to mimic a phosphoryl group is leading to the development of selective inactivators of kinases, phosphatases, and key phosphoryl-utilizing metabolic enzymes.

Producing effective inactivators against an important drug target is only useful for drug development if those inactivators can access that target in a cellular environment. While the sulfonyl group is polar, many candidate compounds contain R groups that are sufficiently hydrophobic in nature to allow compound passage through cellular membranes. For less permeable charged or polar drug candidates, designing compounds that can utilize existing cell uptake systems, such as the peptide uptake systems in the case of cysteine protease inactivators, can be used to enhance cellular uptake and compound targeting.

The task for all new covalent drug candidates is to harness their reactive potential and direct it against selective protein targets. While among the more reactive covalent warheads, vinyl sulfones are still classified as “quiescent affinity labels” [61], compounds that are relatively unreactive towards biologically-relevant nucleophiles but become reactive when bound to a complementary surface with appropriately positioned activating groups. The challenge is to identify and design structures that can selectively deliver the vinyl sulfone groups to these target surfaces. The successful targeting of vinyl sulfones against specific cysteine proteases needs to be replicated against phosphoryl-utilizing enzymes by building vinyl sulfone warheads into the structures of substrate-like compounds. For protein kinases and phosphatases, this involves utilizing the recognition elements around the tyrosyl phosphorylating sites, similar to the successful approach of designing peptide-like inactivators for cysteine proteases. For metabolic enzymes, this involves mimicking the substrate or intermediate structures of the phosphoryl-containing reactants, similar to the approach that has been used to target fungal ASADH. The future of covalent drug development, and the expanding role of vinyl sulfones in this future, is bright.

ASA: aspartate semialdehyde

ASADH: aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase

CDK2: cyclin-dependent kinase 2

EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor

Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2

PET: positron emission tomography

PTKs: protein tyrosine kinases

PTPs: protein tyrosine phosphatases

PVS: phenyl vinyl sulfone

SARS-CoV: severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus

The author thanks Samantha Friday (Ohio University) for conducting the kinetic studies on ASADH, and Dr. Chris Halkides (University of North Carolina Wilmington) for providing the vinyl sulfones used in the ASADH inactivation studies.

REV: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 621

Download: 27

Times Cited: 0