Affiliation:

1Cardiology Unit, Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, AUSL Modena, 41037 Mirandola, Italy

Email: ratticarlo@hotmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1065-2972

Affiliation:

1Cardiology Unit, Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, AUSL Modena, 41037 Mirandola, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2176-6315

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101290 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101290

Received: November 03, 2025 Accepted: December 30, 2025 Published: February 02, 2026

Academic Editor: William C.W. Chen, University of South Dakota, United States

Redesigning cardiovascular services at the local level is a pressing task for decentralized health systems facing the rising burden of chronic cardiovascular disease. In northern Modena (Emilia-Romagna, Italy), a post-restructuring reorganization exposed the limits of hospital-centric models and the need for integrated, patient-centered care. In 2021, Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola—a first-level, non-interventional facility serving a largely rural population—launched a program to build a digitally integrated, prevention-oriented cardiology network. This review distills that field experience into a scalable framework for organizing peripheral cardiovascular services. The Mirandola Cardiology Network evolved along six operational domains: (1) reactivation of the cardiology unit with community outreach; (2) expansion of outpatient services and telecardiology; (3) a day hospital platform for chronic heart failure management; (4) digital transformation of the echocardiography service; (5) development of an advanced imaging center integrating coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography and planned cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and (6) consolidation of professional education, research, and network-wide governance. By combining digital tools, non-invasive imaging, and multidisciplinary collaboration, the model established continuity of care across inpatient, outpatient, and community settings while improving access to diagnostics and appropriateness of care. Although prospective or comparative outcomes are not presented, process indicators and implementation milestones suggest scalability and sustainability, with potential to reduce avoidable admissions and streamline clinical pathways. The Mirandola experience shows that innovation in cardiology is feasible in peripheral settings when investment in technology, governance, and training is aligned with a coherent, value-based vision. It offers actionable guidance for decentralized systems seeking to implement digitally enabled, community-focused cardiology consistent with contemporary recommendations on territorial care and chronic disease management.

Over the past decade, healthcare planning in the northern Modena area (Emilia-Romagna, Italy) has undergone substantial restructuring to improve service accessibility and continuity of care, particularly in rural and underserved communities. This transformation was partly accelerated by the broader reorganization of local infrastructure following the 2012 earthquake, which exposed longstanding vulnerabilities in peripheral healthcare delivery. Within this context, cardiovascular care emerged as a key area for innovation, highlighting the need to strengthen local networks and move beyond traditional hospital-centered models.

Since 2021, a strategic project has been launched to re-establish an autonomous Cardiology Unit at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola—a first-level, non-interventional facility serving a predominantly rural population—and to develop an integrated hospital–community care model aligned with national healthcare reforms promoting chronic disease management and digital integration under Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR, Mission 6) and the principles of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) [1, 2].

This program aimed to rebuild a resilient, patient-centered cardiology service capable of addressing the growing burden of chronic cardiovascular disease in an aging population [3]. Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately one-third of all deaths [3, 4]. Over the last two decades, the traditional hospital-centered model—largely focused on acute and interventional care—has proven inadequate to manage chronic and multi-morbid patients, who require long-term, multidisciplinary follow-up and proactive management. In this context, the transition toward integrated and community-based cardiology represents a pivotal transformation in health service delivery. National and European frameworks now emphasize continuity of care, digital innovation, and equitable access across regions, supporting the creation of community care centers and the use of telemedicine for chronic disease monitoring [3, 5]. These priorities have been further reinforced by recent evidence on digital health implementation [6] and quality indicators for heart failure care [7], which advocate for structured, digitally enabled, outcome-driven cardiovascular networks. This approach is also consistent with the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention, which emphasize system-level coordination, population-based risk assessment, and integrated prevention strategies across all levels of care [8].

The CCM, first introduced by Wagner and colleagues [9], provides the conceptual foundation for this transformation. It promotes a proactive, patient-empowering approach in which individuals, supported by multidisciplinary teams and evidence-based pathways, play an active role in managing their conditions [9]. In Italy, application of the CCM has been shown to improve metabolic control, reduce unplanned hospitalizations, and enhance self-management in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes [9, 10]. Within this framework, the Mirandola project integrates CCM principles with digital health innovation, telecardiology, and data-driven follow-up systems, consistent with recent recommendations by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) on innovation in cardiovascular care delivery [11].

International experiences have demonstrated that integrated models combining hospital and primary care lead to improved efficiency and clinical outcomes. For instance, Hernández-Afonso et al. [12] described a successful one-stop and virtual cardiology system in Spain that significantly reduced waiting times and unnecessary hospital referrals while maintaining quality of care. The initiative applies similar principles within the Italian healthcare framework, adapting them to the local context and leveraging regional healthcare reform and digital infrastructure.

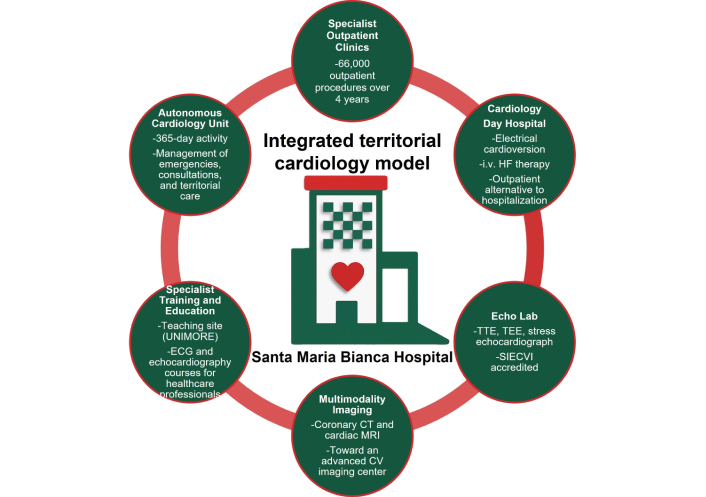

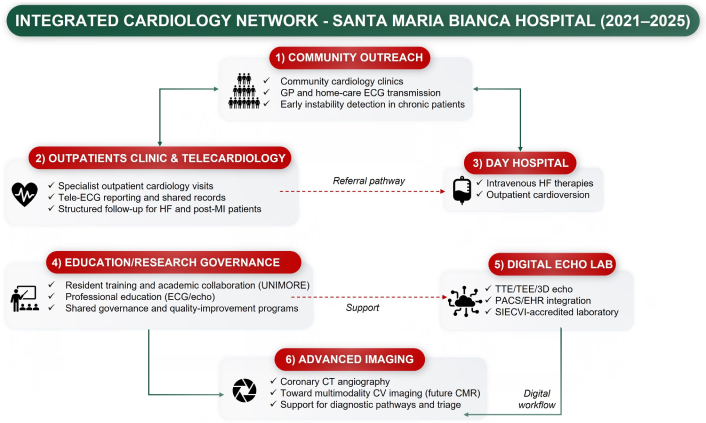

Building on these foundations, the Mirandola Cardiology Network was structured along six operational directions—ranging from consolidation of established services to the development of innovative care pathways—representing a real-world case study of integrated cardiovascular care in a peripheral hospital setting (Figure 1).

Schematic representation of the integrated territorial cardiology model developed at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola (Modena, Italy). The figure summarizes the key components of the restructured Cardiology Unit (2021–2025), including its autonomous clinical governance, extended outpatient network, dedicated day hospital, accredited echocardiography laboratory, multimodality imaging development, and structured training programs. UNIMORE: University of Modena and Reggio Emilia; ECG: electrocardiogram; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CV: cardiovascular; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; SIECVI: Italian Society of Echocardiography and Cardiovascular Imaging; HF: heart failure.

This manuscript provides a structured overview of this experience, presenting a descriptive, narrative review of the reorganization project implemented between 2021 and 2025 at the Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola (Modena, Italy). Quantitative indicators—including the number and type of procedures, outpatient clinic volumes, and imaging activities—were retrospectively obtained from the hospital’s electronic health records and scheduling systems. Qualitative data, including organizational changes, workflow redesigns, and implementation phases, were extracted from internal documentation, project reports, and clinical governance materials. No prospective data collection or hypothesis testing was performed.

To enhance transferability, the structure of the review aligns with core domains of implementation science. While not strictly applying a formal framework such as RE-AIM or CFIR, the analysis reflects their underlying principles by addressing Reach (population served), Effectiveness (care coordination and access), Adoption (integration across clinical teams), Implementation (digital tools and workflows), and Maintenance (governance and scalability). This framework may support replication and contextual adaptation in other decentralized health systems.

Rather than aiming for hypothesis testing or inferential analysis, the objective of this work is to illustrate a transferable and exportable framework for integrated cardiovascular care, emphasizing its feasibility in resource-limited or decentralized settings. The review, therefore, combines local implementation data with a literature-based contextualization of organizational and technological strategies in modern cardiology.

This manuscript is conceived as a descriptive, real-world report of an organizational transition. Its purpose is to outline the implementation framework rather than to quantitatively evaluate clinical outcomes, which are being collected in ongoing prospective analyses.

We performed a narrative search of PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus for publications from Jan 2010 to Oct 2025 using combinations of the following terms: cardiology service reorganization, integrated care, telecardiology, heart failure chronic care, echocardiography digital, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) gatekeeping, value-based care, and hub-and-spoke. We prioritized international guidelines/position statements [ESC/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI)/ACC/American Heart Association (AHA)], consensus documents, systematic reviews, and implementation studies relevant to decentralized settings.

To contextualize organizational aspects in the Italian healthcare system, we also considered national/local sources—including Italian-language articles from the Italian Journal of Cardiology [Giornale Italiano di Cardiologia (GIC)] and authoritative grey literature (e.g., national/regional health agency documents)—when they provided concrete evidence on feasibility, workflows, or governance of spoke-level services.

We excluded single case reports and studies outside cardiovascular care. Additional references were identified by screening citations of key articles and relevant grey literature from authoritative agencies on integrated-care models. The synthesis is descriptive and aims to map operational domains, enablers, and transferability, rather than provide a quantitative meta-analysis.

Between 2021 and 2025, a comprehensive clinical and organizational restoration of the local Cardiology Unit was completed, transforming it into a fully functional, outpatient-based spoke center within an integrated provincial cardiovascular network. The unit now operates as a reference spoke for non-invasive cardiology within the provincial system, providing daily specialist coverage for outpatient and emergency consultations and full clinical governance of diagnostic and day hospital activities. Night-time emergencies are centralized at the nearest interventional cardiology center, which guarantees 24/7 hemodynamic and electrophysiology support through teleconsultation and fast-track referral pathways.

From 2022, the cardiology service was progressively extended to community-based outpatient centers, integrated into hospital governance, and operating on scheduled days. These clinics, supported by telemedicine and direct communication channels with general practitioners, provide specialist evaluation and follow-up closer to patients’ homes, enabling shared management of chronic cardiovascular conditions, earlier identification of clinical instability, and redistribution of routine visits for semi-rural populations.

This reorganization embodies the principles of integrated cardiovascular care, aligning with the ESC recommendations for networked and patient-centered cardiac services [13]. The system adopts a hub-and-spoke structure combining decentralized diagnostic capacity and specialist expertise with centralized access to interventional and advanced imaging services. Similar frameworks have been endorsed by the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP) of the ESC, which advocates for whole-system approaches placing the patient at the center and emphasizing multidisciplinary coordination supported by digital health technologies [14]. Multidisciplinary pathways, including perioperative cardiovascular assessment and cardio-oncology follow-up, operate through shared electronic documentation and scheduled interdisciplinary interactions tailored to clinical needs rather than fixed session frequencies.

From an international perspective, this experience aligns with the AHA’s “Learning Healthcare System” paradigm, where data flow, teleconsultation, and continuous feedback loops between clinicians and patients generate adaptive, evidence-based care models [15]. Embedding cardiologists within community settings has been shown to facilitate early detection of decompensation, optimize therapy titration, and improve adherence to follow-up in chronic heart failure and ischemic heart disease—core outcomes also emphasized by the ESC and AHA frameworks [13–15]. This structure represents a scalable, exportable model for cardiovascular networks: one that enhances access to specialist expertise, integrates digital and human resources, and promotes a culture of shared decision-making across the continuum of care. As highlighted by Nicholson et al. [16], sustainable integration of hospital and community cardiology requires clear governance, interoperable communication systems, and multidisciplinary engagement to ensure long-term effectiveness, sustainability, and adaptability across different healthcare systems.

Building on the reorganization of the cardiology network, outpatient services were substantially expanded and digitally integrated between 2021 and 2025. Over this period, the Cardiology Unit delivered more than 66,000 procedures—including electrocardiograms (ECGs), echocardiographic studies, Holter monitoring, and specialist consultations—reflecting not only increased activity but a strategic shift toward an integrated, technology-enabled care model serving the northern Modena area.

A key component of this transformation was the implementation of an interoperable telecardiology reporting system connecting outpatient clinics, community care centers, and home-care services. Through secure digital platforms, ECGs and other diagnostic data are transmitted, interpreted, and reported in real time by cardiologists, thereby enabling rapid turnaround and immediate feedback to general practitioners, in line with published telecardiology experiences. This approach aligns with the growing international emphasis on telemedicine-supported continuity of care for patients with chronic and complex cardiovascular conditions [17–19]. Telecardiology has emerged as one of the most effective applications of digital health in cardiovascular medicine, supporting early diagnosis, rapid triage, and continuous management of chronic disease. A systematic review of 50 studies confirmed that telecardiology consistently improves clinical outcomes—particularly in early detection, timely intervention, and reduced hospitalizations—while also lowering healthcare costs [20]. Similar results have been reported across Europe, where regional telecardiology networks have shortened ECG reporting times from over 60 min to less than 10 min, thereby reducing emergency delays and optimizing resource allocation [18, 19]. The telecardiology platform enables secure ECG transmission from community and home-care settings, centralized cardiologist reporting, and seamless interoperability with the hospital electronic health record, ensuring real-time availability of traces across the care network.

Parallel to digital integration, the outpatient network was expanded to include specialized cardiology clinics covering nearly all major subspecialties—heart failure, arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease, and cardiomyopathies—ensuring coordinated, evidence-based management across the continuum of care, in accordance with current ESC guidelines (Table 1) [21–23].

Specialist outpatient clinics established at the Cardiology Unit of Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola (2021–2025), with frequency and main clinical activities.

| Clinic | Frequency | Main activities/notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric cardiology | Weekly | CUP access with reserved slots for the Pediatric Unit |

| Second-level echocardiography techniques | Monthly | Transesophageal echo, exercise stress echo, pharmacologic stress echo |

| Arrhythmology | Weekly | Pacemaker and ICD follow-up, tilt testing |

| Heart failure | Weekly | Dedicated care pathway, in collaboration with general practitioners |

| Post-myocardial infarction | Weekly | Early post-discharge follow-up |

| Cardiomyopathies | Monthly | Diagnostic work-up and follow-up |

| Exercise testing | Daily | CUP-based access |

| ECG and cardiology consultations | Daily | First evaluations and follow-up visits |

| Level I echocardiography | Daily | CUP-based access and routine follow-up |

CUP: Centro Unico di Prenotazione (Italian centralized booking system for outpatient services); ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ECG: electrocardiogram.

Public engagement initiatives—such as open cardiology events, cardiovascular risk screenings, and community-based educational programs—have played a key role in bridging hospital services with the local population. These activities also support early identification of underdiagnosed or hereditary cardiac conditions, such as cardiomyopathies, in line with the ESC 2023 Guidelines, which emphasize community outreach and population-level awareness as tools for improving timely diagnosis and access to care [21].

Altogether, the expansion of outpatient and telecardiology services represents a scalable and exportable model of digitally integrated community cardiology—a framework that enhances diagnostic efficiency, supports multidisciplinary collaboration, and promotes equitable access to specialist expertise. This experience serves as a transferable model for health systems seeking to modernize outpatient cardiovascular care through digital and community integration.

In 2024, a dedicated cardiology day hospital was established at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola, as part of the ongoing reorganization of local cardiovascular care. The unit currently provides same-day procedures, primarily electrical cardioversion for patients with atrial fibrillation, in accordance with the 2024 ESC Guidelines on atrial fibrillation, which emphasize structured and timely rhythm-control strategies for symptomatic patients [24].

The day hospital is now evolving into a multifunctional platform for advanced heart failure management, with programs under implementation to include intravenous iron repletion, outpatient diuretic therapy, and intermittent infusions of levosimendan for patients with advanced or worsening heart failure. These interventions are designed to reduce avoidable hospitalizations and provide a safe, monitored environment for decompensated or high-risk patients.

The 2023 ESC Focused Update on heart failure and recent evidence highlight the growing role of outpatient intravenous therapies—particularly iron and diuretics—in stabilizing patients with chronic or worsening heart failure and preventing the need for full hospitalization [22, 23, 25, 26]. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose holds a Class I, Level A recommendation in ESC guidelines for improving quality of life and reducing heart failure hospitalizations in iron-deficient patients [22, 23, 27]. Similarly, intermittent levosimendan infusions have shown clinical benefit in advanced heart failure, improving symptoms and hemodynamics while reducing the risk of readmission [28].

This approach reflects the emerging international paradigm of “dehospitalizing” heart failure care, shifting intensive management to controlled outpatient environments. The day hospital model effectively addresses the “worsening heart failure” phase described by Greene et al. [26], in which patients deteriorate despite stable chronic therapy but may be stabilized through early, protocol-driven outpatient interventions. By providing prompt access to intravenous therapies, hemodynamic monitoring, and specialized nursing support, the day hospital functions as an intermediate step between ambulatory care and full hospitalization, optimizing resource utilization and ensuring patient-centered continuity of care.

Concurrently, structured internal diagnostic and therapeutic pathways were implemented to guarantee seamless multidisciplinary management within the hospital. These include a pre-operative cardiovascular assessment pathway integrated with anesthesiology for perioperative risk stratification; a cardio-oncology program for patients receiving potentially cardiotoxic therapies, consistent with ESC recommendations on cancer therapy-related cardiovascular toxicity; and structured post-discharge cardiology follow-up for patients released from medical, pulmonary, and long-term care units or from the emergency department, ensuring early reassessment and optimization of therapy.

Together, these initiatives create a fully integrated continuum of care connecting inpatient, outpatient, and community services within a shared governance framework. The day hospital-centered model represents a practical approach that may support regional and national efforts to improve chronic cardiovascular care, streamline admissions, and facilitate coordination across levels of service delivery.

Since 2022, the echocardiography service at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola—a first-level, non-interventional facility—has undergone a full digital transformation, becoming a fully networked and data-driven imaging environment. Structured electronic reporting, image archiving, and seamless integration within the institutional information system have enabled longitudinal tracking of patients, immediate comparison of serial examinations, and rapid sharing of data with tertiary referral centers. This interoperability represents a cornerstone of modern cardiovascular imaging, consistent with EACVI and ESC frameworks for standardization, data governance, and inter-hospital collaboration [29, 30].

The introduction of a stress echocardiography program in the same year expanded the service’s diagnostic capacity for ischemic heart disease, preoperative risk assessment, and unexplained dyspnea. Embedded within a multidisciplinary workflow, stress imaging supports early functional characterization and contributes to more cost-effective diagnostic pathways—reflecting the European and North American trend toward functional-first, multimodality triage, as endorsed by the EACVI and the American Society of Echocardiography [31, 32].

In 2023, the service acquired next-generation echocardiography systems through national recovery funding, enabling real-time 3D reconstruction. This upgrade allowed the implementation of 3D transesophageal imaging for the structural heart disease program, with direct digital image sharing and joint case planning with a tertiary surgical hub. Such a hub-and-spoke model—where peripheral centers provide diagnostic precision while tertiary institutions perform the intervention—has proven effective in enhancing equity of access, reducing waiting times, and optimizing procedural selection across healthcare networks [33–36].

Building upon this infrastructure, the unit introduced speckle-tracking strain analysis in 2025, expanding deformation imaging to detect subclinical ventricular dysfunction in patients with cardiotoxic exposure, diabetes, or cardiomyopathy, in alignment with ESC cardio-oncology and heart failure recommendations [37, 38]. Strain imaging now serves as a key biomarker in longitudinal cardiac monitoring, offering predictive insight well before conventional functional deterioration occurs [39–41].

National surveys by the Italian Society of Echocardiography and Cardiovascular Imaging (SIECVI) indicate that while 3D and strain imaging technologies are increasingly available, their adoption into routine clinical practice remains heterogeneous [42]. Through structured digital implementation, continuous training, and interoperability with referral centers, the local echocardiography unit addressed several practical barriers, offering a model that may inform modernization efforts in other regional centers.

Finally, the echocardiography service achieved official accreditation by the SIECVI, confirming its technical quality, standardized protocols, and compliance with professional training requirements [43].

This digital evolution anticipates the next generation of integrated cardiovascular imaging, where interoperability and multimodality define both clinical excellence and system sustainability.

The progressive digital evolution of echocardiography at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola has laid the foundation for the development of a comprehensive cardiovascular imaging center integrating multimodal, non-invasive diagnostics to enhance patient management and optimize resource allocation.

In early 2025, the center completed its transition into a digitally connected spoke facility equipped with CCTA, in collaboration with the Department of Radiology. This milestone represented a strategic advance for hospitals without on-site catheterization laboratories, enabling high-resolution, non-invasive visualization of the coronary arteries and providing an effective gatekeeping tool for invasive coronary angiography [44–46].

The introduction of CCTA has proven transformative in spoke settings, allowing rapid exclusion of significant coronary artery disease in low- to intermediate-risk patients and improving referral appropriateness to tertiary centers. The modality’s capacity to combine anatomical and functional assessment aligns with contemporary EACVI and ESC recommendations emphasizing early diagnosis and precision stratification in chronic coronary syndromes [47–49]. By detecting both obstructive and non-obstructive atherosclerosis, cardiac CT supports a preventive, precision-medicine approach centered on personalized therapy and risk-factor modification, consistent with the 2024 ESC Guidelines for chronic coronary syndromes [50].

In parallel, the installation of a 1.5-T magnetic resonance scanner—upgradeable with dedicated cardiovascular software—will enable future implementation of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), completing the imaging spectrum. CMR will provide high-resolution myocardial tissue characterization, including mapping of edema, fibrosis, and fat infiltration, complementing the anatomical precision of CT and the functional insight of echocardiography [51–53].

Together, these technologies contribute to the development of a comprehensive cardiovascular imaging facility, capable of addressing a wide range of diagnostic needs—from early ischemia detection to the phenotyping of complex cardiomyopathies. The integration of CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within a single digital infrastructure reflects current trends in cardiovascular imaging toward multimodality, interoperability, and network-based care [54, 55].

This configuration enhances the diagnostic capabilities of the spoke center while maintaining effective collaboration with tertiary hubs, supporting efficient, safe, and equitable access to advanced imaging.

In addition to its clinical benefits, this evolution appears to be economically viable. Data from Italian multicenter studies suggest that cardiac CT and MRI can reach the break—even point within spoke settings, when incorporated into structured diagnostic pathways—highlighting the long-term sustainability of such investments [56].

Rather than representing a singular innovation, this experience shows how targeted technological upgrades—combined with digital integration and governance—can strengthen the role of peripheral hospitals within regional imaging networks. It may serve as a useful reference for other systems aiming to enhance imaging services in decentralized care environments.

Since 2022, the Cardiology Unit of Santa Maria Bianca Hospital, Mirandola has progressively adopted a model that integrates clinical service, professional training, and research within the broader framework of the regional cardiovascular network. As an accredited teaching site for the Postgraduate School of Cardiology at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (UNIMORE), the unit incorporates cardiology residents into all aspects of care, including outpatient services, advanced imaging, and community-based activities. This approach reflects the European concept of “learning health ecosystems”, where clinical environments are designed to generate continuous feedback, promote innovation, and support the development of future professionals [15].

In addition to formal academic programs, the center fosters a scientific and interdisciplinary culture through initiatives such as the national meeting “Mirandola con il Cuore”, which promotes dialogue between cardiology, internal medicine, and digital health stakeholders. These activities strengthen the integration of hospital, academia, and community—key dimensions of sustainable cardiovascular systems, as outlined in the 2025 position paper of the Italian Association of Hospital Cardiologists (ANMCO) on the future of hospital cardiology and workforce sustainability [57].

Participation in national heart failure networks and multicenter studies promoted by ANMCO and the Italian Society of Cardiology (SIC) further aligns the institution with shared-care models based on standardized documentation, structured protocols, and integrated patient management. These models, supported by the ANMCO-SIC Heart Failure Network framework [58], have been associated with improved clinical coordination, reduced variability, and more efficient use of healthcare resources.

Continuous medical education is embedded into clinical operations through regular in-house courses on ECG interpretation, emergency care, and advanced echocardiography. This system supports interdisciplinary competence and aligns with the CCM, which promotes professional empowerment, proactive team-based care, and shared responsibility in the management of chronic cardiovascular conditions [5].

Rather than representing an isolated case, this experience may offer a useful example of how spoke-level hospitals can integrate education, research, and innovation to support improvements in service delivery. The approach is consistent with current priorities in cardiovascular health policy and could contribute to broader efforts aimed at promoting sustainability and modernization within regional care networks.

On this basis, the following discussion reflects on how the Mirandola initiative applies key principles of integrated, digitally supported cardiovascular care in a decentralized setting.

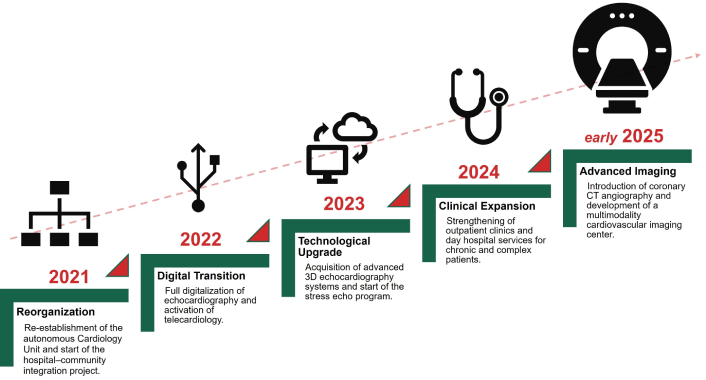

The project’s progressive implementation—through five developmental phases spanning reorganization, digital transition, technological upgrade, clinical expansion, and advanced imaging integration—is summarized in Figure 2.

Evolution timeline of the Mirandola cardiology project (2021–2025). The five sequential phases include reorganization of the cardiology network (2021), digital transition (2022), technological upgrade (2023), clinical expansion (2024), and the introduction of coronary CT angiography and early development of an advanced multimodality imaging center in early 2025. CT: computed tomography.

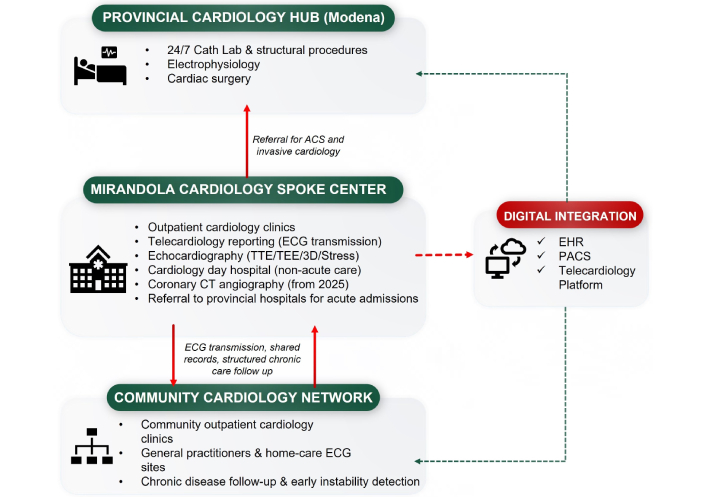

This case study shows how a digitally connected, prevention-oriented cardiology network can be implemented in a first-level, non-interventional hospital and integrated within a hub-and-spoke system, achieving continuity of care across inpatient, outpatient, and community settings (Figure 3) [14, 15, 23].

Provincial hub-and-spoke cardiology network in northern Modena. The diagram summarizes the organizational relationships between the provincial cardiology hub in Modena, the Mirandola spoke center, and the community cardiology network. Red arrows indicate clinical referral pathways for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and invasive cardiology, as well as structured chronic-care follow-up between community clinics and the spoke center. Green dashed lines depict digital integration through interoperable electronic health records (EHRs), picture archiving and communication systems (PACS), and the telecardiology reporting platform. Red dashed arrow indicates digital referral and reporting workflows between the spoke center and the digital integration platform. ECG: electrocardiogram; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; CT: computed tomography.

These principles are consistent with international evidence on integrated cardiovascular care. Consistent with the ESC framework proposed by Ski et al. [14], the model emphasizes digital communication, multidisciplinary coordination, and patient-centered pathways [19].

From a service delivery perspective, the Mirandola configuration aligns with the “unified value” concept proposed by Thakkar [59] in The British Journal of Cardiology, which emphasizes value generation across the whole patient journey rather than within isolated units. The project’s ability to facilitate shared clinical decision-making, optimize diagnostic gatekeeping (e.g., via CCTA), and streamline referrals echoes the need for dynamic, patient-centric models integrated across hospital, community, and social care [59].

The model also resonates with implementation principles identified in reviews of integrated heart failure care. MacInnes and Williams [60] highlight that multidisciplinary education, early follow-up, shared pathways, and liaison between hospital and primary care are essential components of successful heart failure models. These elements are mirrored in Mirandola’s structured discharge pathways, telecardiology follow-ups, and community-enabled chronic disease management.

Importantly, international implementation reports show that integrating CCTA as a gatekeeper test improves the appropriateness of downstream invasive procedures and reduces avoidable admissions. Several European and U.S. studies confirm that early outpatient CCTA, when coupled with structured follow-up, can serve as a filter for invasive angiography and reduce diagnostic delays [61–63].

These findings illustrate how the Mirandola model operationalizes vertical integration in a non-tertiary context, enhancing diagnostic access without 24/7 cath lab infrastructure and contributing to a more coordinated distribution of care across hospital levels.

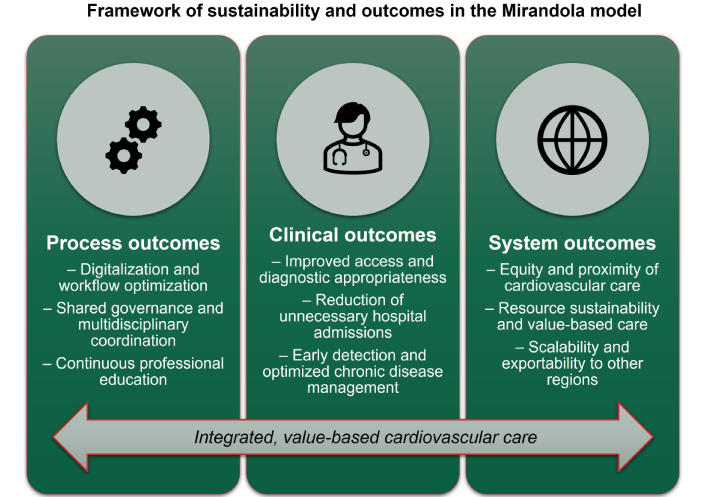

The overall conceptual framework linking process, clinical, and system outcomes is summarized in Figure 4. This tripartite framework aligns with international experiences in value-based cardiovascular care, emphasizing the integration of process and outcome metrics, multidisciplinary collaboration, and equity of access.

Framework of sustainability and outcomes in the Mirandola cardiology model. The figure summarizes the hierarchical progression from process outcomes (digitalization, shared governance, and professional education) to clinical outcomes (improved access, appropriateness, and chronic care optimization), culminating in system outcomes (equity, sustainability, and scalability). Together, these dimensions underpin an integrated, value-based model of cardiovascular care.

As with all decentralized models, scalability will depend on maintaining adequate digital infrastructure, workforce training, and alignment with regional reimbursement and governance policies—factors that vary across health systems and should be considered when adapting this framework.

Recent reports highlight that value-based transformation is most effective when implemented through coordinated regional models, particularly in decentralized or underserved settings, where outcome-driven feedback loops can guide continuous improvement [64–66].

More broadly, this initiative provides a replicable blueprint for decentralized health systems aiming to modernize cardiovascular care delivery through digitalization, multidisciplinary collaboration, and continuous professional development (Figure 5).

Logical integration of the six operational domains in the Mirandola Cardiology Network (2021–2025). The diagram illustrates how each operational domain contributes to the development of the integrated cardiology model. Community outreach interacts bidirectionally with outpatient clinics and telecardiology activities; outpatient care channels clinical instability toward the day hospital; the digital echocardiography laboratory provides the technological foundation for advanced cardiovascular imaging; and education-research-governance offer transversal support across all domains. Together, these interconnected components form the integrated cardiology network implemented at Santa Maria Bianca Hospital. Green arrows indicate structured bidirectional integration pathways between operational domains, while red dashed arrows indicate referral or support pathways. GP: general practitioner; ECG: electrocardiogram; HF: heart failure; MI: myocardial infarction; UNIMORE: University of Modena and Reggio Emilia; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography; TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; PACS: picture archiving and communication systems; EHR: electronic health record; SIECVI: Italian Society of Echocardiography and Cardiovascular Imaging; CT: computed tomography; CV: cardiovascular; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance.

The model also resonates with the preventive perspective promoted by the 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention, which encourage earlier risk identification and closer coordination between hospital and community care [8].

Because the reorganization process is still ongoing, formal outcome indicators such as emergency department presentations, readmission rates, waiting times, and diagnostic performance metrics were not included, as they are currently being prospectively validated.

While the model presented here offers a potentially transferable framework for integrated cardiovascular care, several of its components are closely linked to the specific context in which it was implemented. Key enabling factors included strong regional governance, dedicated funding through Italy’s PNRR, and an established partnership with the UNIMORE, which facilitated staff training and academic integration. Leadership continuity and a collaborative culture among hospital teams also played a central role in sustaining the project across multiple implementation phases.

Accordingly, the scalability of this model will depend on local resource availability, institutional commitment, and alignment with regional or national health policies. Rather than representing a rigid blueprint, the Mirandola model should be considered a flexible framework that can be adapted to meet the needs and capacities of different healthcare systems.

Importantly, the clinical expansion phase was achieved largely through reorganization of existing staff and optimization of digital workflows, rather than through substantial increases in cardiology or nursing personnel. In terms of workforce, this allowed the model to remain largely resource-neutral, enhancing its scalability in other decentralized settings, while capital investments were supported by dedicated national funding mechanisms, including allocations from the Italian PNRR.

Comparable integrated-care models have been implemented internationally—such as the National Health Service (NHS) Integrated Care Systems in England, the Kaiser Permanente model in the United States, and the nationwide cardiac registry framework in Denmark—showing that hospital–community integration can improve coordination and accountability even in large, decentralized systems [67–69].

As a descriptive, single-center experience, this report focuses primarily on organizational structure and process outcomes rather than comparative or quantitative analyses. The absence of control groups or prospective outcome data limits the ability to determine the specific contribution of each intervention and to compare performance directly with other regional models. Moreover, organizational and policy environments vary across regions, and some structural enablers observed in this case—such as targeted funding mechanisms, governance stability, and academic affiliations—may not be uniformly available in other healthcare systems.

Additional structural limitations may affect the transferability of the model. Implementation of digitally integrated cardiovascular pathways requires sustained investment in IT infrastructure, interoperability standards, and cybersecurity, which may not be feasible in all decentralized settings. Moreover, the adoption of advanced imaging and telemedicine workflows depends on dedicated staff training, protected time for education, and continuous technical support—factors that have historically varied across regions. Differences in reimbursement policies, digital maturity, and workforce availability may also influence scalability, particularly in health systems without centralized governance or targeted funding mechanisms such as those provided through the Italian PNRR. These contextual barriers should be acknowledged when extrapolating this experience to other regions.

Quantitative evaluations of key indicators—such as rehospitalization rates, diagnostic yield, cost-effectiveness, and patient-reported outcomes—are ongoing and will be essential to confirm the long-term impact and scalability of the model. Preliminary internal observations were not included in this manuscript, as formal quantitative evaluation of patient outcomes is still ongoing.

Future priorities include maintaining the achieved quality level, expanding day hospital services and telecardiology coverage, and investing in next-generation technologies such as three-dimensional echocardiography, cardiac MRI, and artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted analytics for precision cardiovascular imaging. Continued collaboration among hospitals, community care centers, and academic institutions will be crucial to consolidate these results and extend the model to other regions. Looking ahead, multicenter collaborations and prospective evaluations will be needed to validate the model’s adaptability and impact in diverse healthcare settings.

While the descriptive activity data used in this report were obtained retrospectively from existing clinical systems, future evaluations of clinical and economic outcomes will be based on prospectively collected datasets within dedicated quality-improvement or research protocols.

The model’s clinical impact has not yet been evaluated quantitatively. Comparative analyses—whether against historical baselines or external control regions—are planned but were outside the scope of this descriptive framework.

This experience demonstrates that meaningful innovation in cardiovascular care can arise not only in large academic centers or tertiary hospitals, but also in smaller, resource-limited settings—provided that digital tools, professional education, and shared governance are effectively deployed. The Mirandola model illustrates how targeted reorganization and strategic technological investment can reshape a local cardiology service into a structured, interoperable, and patient-centered system aligned with international guidelines.

While grounded in a specific territorial context, the operational principles underpinning this model—interdisciplinary collaboration, telemedicine integration, diagnostic autonomy through non-invasive imaging, and continuous training—are broadly adaptable and scalable. As such, this project should not be interpreted as a self-referential narrative, but rather as a concrete framework potentially transferable to other decentralized health systems, both in Italy and internationally.

By bridging the gap between hospital and community care, optimizing diagnostic workflows, and embedding digital continuity across care levels, the Mirandola experience offers a practical contribution to the ongoing transformation of cardiovascular service delivery. It represents a replicable example of how value-based, integrated care can be implemented in real-world, non-metropolitan environments—and as such, it may serve as a useful reference for clinicians, administrators, and policymakers seeking sustainable models of innovation.

ACC: American College of Cardiology

AHA: American Heart Association

ANMCO: Italian Association of Hospital Cardiologists

CCM: Chronic Care Model

CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography

CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance

CT: computed tomography

EACVI: European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging

ECGs: electrocardiograms

ESC: European Society of Cardiology

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

PNRR: Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan

SIC: Italian Society of Cardiology

SIECVI: Italian Society of Echocardiography and Cardiovascular Imaging

UNIMORE: University of Modena and Reggio Emilia

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) to assist with language editing and structure refinement. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

CR: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. EM: Investigation, Data curation. BV: Investigation, Data curation. AM: Writing—review & editing. GL: Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 464

Download: 32

Times Cited: 0