Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

Email: ayesha34aman@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7503-5937

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8539-732X

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4891-6359

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-9105-9725

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8417-5886

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2206-937X

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7578-0827

Affiliation:

2Department of Medicine, Shalamar Medical and Dental College, Lahore 54840, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0225-6551

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-6574-7089

Affiliation:

3Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5621-6562

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101289 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101289

Received: December 09, 2025 Accepted: January 07, 2026 Published: January 23, 2026

Academic Editor: Guoliang Meng, Nantong Universtiy, China

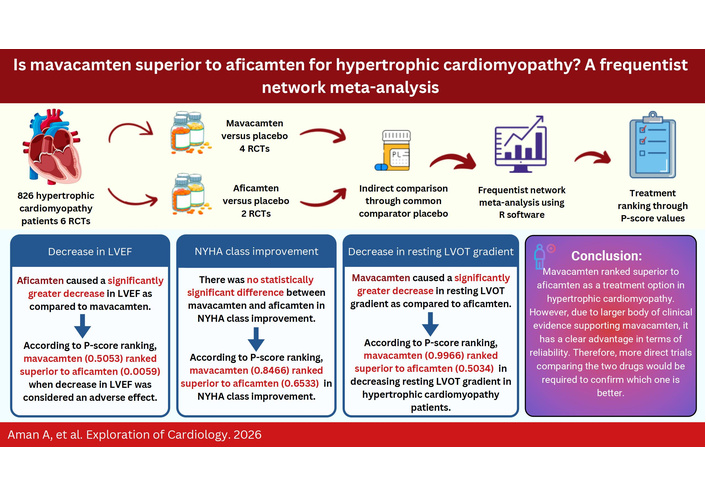

Background: Myosin inhibitors have been shown to improve exercise capacity and symptoms, as well as reduce the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient. This study explores the efficacy of mavacamten versus aficamten in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients.

Methods: From the inception to October 2024, the electronic databases [Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov] were searched. Using a random-effects model and a frequentist framework, specific effect sizes [mean difference (MD) and risk ratio (RR)] were pooled.

Results: This network meta-analysis included six randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A total of 826 individuals with HCM were included; 443 of them received a cardiac myosin inhibitor, while 383 received placebo. Comparison of aficamten versus mavacamten through a common comparator, placebo, showed that aficamten caused a lesser decrease in resting LVOT gradient than that of mavacamten [MD = 14.74, 95% CI (3.02; 26.47)]. Therefore, mavacamten ranked higher (P-score = 0.9966) than aficamten (P-score = 0.5034) in decreasing resting LVOT gradient. Aficamten significantly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in contrast to mavacamten [MD = –5.59, 95% CI (–10.43; –0.75)]. According to P-score ranking, mavacamten (0.5053) ranked higher than aficamten (0.0059). For New York Heart Association (NYHA) class improvement, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups [MD = –0.37, 95% CI (–1.79; 1.06)]. But P-score ranked mavacamten (0.8466) higher than aficamten (0.6533).

Discussion: Mavacamten ranked superior to aficamten in HCM management. However, this ranking is based not on the absolute clinical benefit but on the network point estimates. Additionally, due to a larger body of clinical evidence supporting mavacamten, it has a clear advantage in terms of reliability. Therefore, more direct trials comparing the two drugs would be required to confirm which one is better and provide conclusive evidence.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a prevalent heart condition primarily affecting sarcomere-related genes and is characterized by increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness and asymmetric septal hypertrophy [1]. Imaging-based detection of the disease phenotype suggests a prevalence of 1 in 500 (0.2%) in the general population [2]. HCM is linked to an annual mortality rate of approximately 1%, with sudden cardiac arrest, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation being the key contributors to the increased risk of mortality in affected individuals [3]. LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, caused by the high rate of actin-myosin interactions, holds an important prognostic value for patients with HCM and therefore is the main therapeutic target [4]. Conventional pharmacologic therapies like beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and disopyramide relieve symptoms but do not affect the underlying pathology [5].

Recently, cardiac myosin inhibitors have been found effective in reducing myocardial contractility. Mavacamten is a first-in-class myosin inhibitor that inhibits its cross-binding with actin, thereby reducing the contractile force which is believed to be the major contributor to LVOT obstruction. Mavacamten has been shown to decrease LVOT gradients and improve functioning in HCM patients [6]. Aficamten is a newer drug that binds to a distinct allosteric site and inhibits actin-myosin cross bridges [7]. Previous studies have well demonstrated the efficacy and safety of mavacamten in reducing myocardial wall stress. This is also associated with the fact that it is well tolerated by a large percentage of the population [8]. Mavacamten has been compared with a placebo in various studies in different ethnic groups, with the results predominantly in favor of mavacamten in primary and secondary outcomes [9]. It has also shown promising effects on health status in HCM patients [10]. Aficamten, which is a newer drug and has yet to have FDA approval, has also been compared with a placebo and tested for its efficacy and safety. It has also shown a substantial amount of improvement in oxygen uptake and LVOT gradients when compared with a placebo. This underlines the potential of sarcomere-targeted therapy [11]. However, there are no trials that compare mavacamten and aficamten directly with each other and determine which one gives better results in terms of efficacy and safety.

This network meta-analysis aims to pool the evidence from pre-existing literature and compare aficamten and mavacamten indirectly via a common comparator (placebo) in order to rank the two myosin inhibitors. Clinicians can benefit from the findings this study provides in optimizing patient care.

This network meta-analysis was conducted following the guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [12] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13]. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the identifier CRD42025635255.

We searched the online databases Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov, from inception to October 2024. The search terms, along with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used, are as follows: ‘Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy’, ‘cardiac myosin inhibitors’, ‘Mavacamten’, and ‘Aficamten’. EndNote software was used to import the relevant studies and remove duplicates. Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts separately. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any conflicts. The detailed search strategy is given in Table S1.

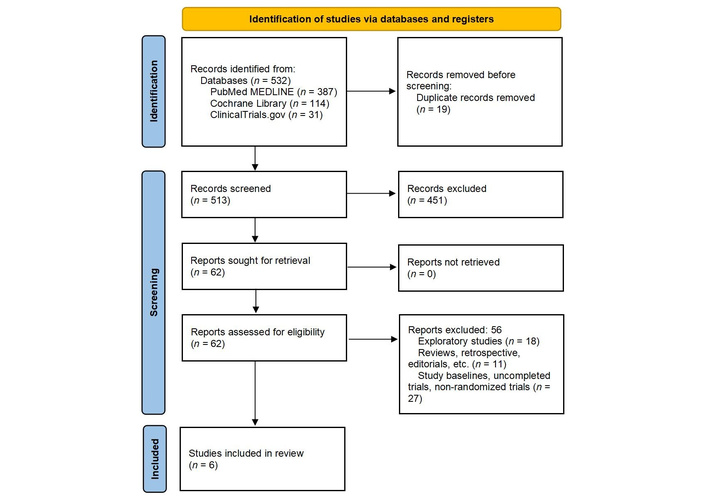

Two reviewers screened the full texts of the articles with a third reviewer acting as an adjudicator, and the studies considered to meet the eligibility criteria were included. The selection process is presented in the form of a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows (Table S2): (1) participant population: patients having HCM; (2) intervention: cardiac myosin inhibitors (mavacamten or aficamten); (3) comparator: placebo; (4) primary outcome: change in resting LVOT gradient and secondary outcomes: decrease in LV ejection fraction (LVEF), proportion of patients achieving at least one New York Heart Association (NYHA) class improvement; (5) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The exclusion criteria were as follows: any study design other than RCTs, quasi-randomized trials, animal studies, observational studies, and patients not being treated with cardiac myosin inhibitors.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of included and excluded trials. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Adapted from [13]. © 2026 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Licensed under a CC BY 4.0.

Data related to the baseline study characteristics (author, publication year, country, gender as the percentage of male population, age, total participants, study duration, intervention details, and background therapy) were extracted using an Excel sheet. Outcomes data for change in resting LVOT gradient and decrease in LVEF from baseline were extracted as mean differences (MDs) and standard errors (SEs), which were calculated, while for patients achieving NYHA class improvement, as risk ratio (RR) and SE.

The revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for RCTs (RoB 2.0) [14] was used for quality assessment of the included trials. The domains assessed were risk of bias resulting from the randomization process, deviations from the intended intervention, missing outcome data, measuring the outcome, and selective reporting of results. Risk of bias was indicated as being “high”, “low”, or “some concerns” [15]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the authors. Publication bias was not assessed as the number of included studies was less than 10 [16].

Statistical analyses were performed using the R-software netmeta and netrank package (R version 4.3.2) [17]. A frequentist framework [18] was employed, utilizing random-effects models for pooling study-specific effect sizes (RRs and MDs). This framework was utilized to minimize subjectivity created by prior specification and to provide robust estimates appropriate for the size of available evidence. Cochraneʼs Q test and I2 index, with P-value < 0.1, were used to assess heterogeneity. A network diagram was generated to visually represent all treatment comparisons, with the size of the nodes and connections reflecting the number of studies and the number of participants, respectively. The assumptions of transitivity were evaluated by comparing the baseline characteristics (e.g., age, NYHA class), follow-up duration, and disease severity across all the trials included in the network. Consistency was assessed using a node-splitting approach to compare direct and indirect evidence for each pairwise treatment comparison within the network [19]. Treatment ranking was done using P-score values, which reflect relative ranking based on the point estimates and SE of frequentist network estimates but not absolute clinical benefit [20].

A total of 532 studies were retrieved from the electronic databases (Cochrane, PubMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov). After removing the duplicates and doing primary screening, 62 articles remained. Full-text screening of those 62 articles was conducted, and a total of 6 RCTs were selected according to the inclusion criteria. The screening process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Six RCTs were included in our network meta-analysis. A total of 826 HCM patients were included, with a mean age ± SD of 59.8 ± 14.2 years in the intervention vs. 60.9 ± 10.5 years in the placebo, of which 443 received a cardiac myosin inhibitor, and 383 received a placebo. All studies had patients having background beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker therapy. Detailed characteristics of included studies, together with intervention details and baseline patient characteristics, are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Study characteristics and intervention details.

| Study ID | Trial | Location | Study design | Blinding | Population | Number of patients (intervention/placebo) | Study duration | Intervention | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mavacamten | |||||||||

| Olivotto et al. 2020 [10] | EXPLORER-HCM | Multi-national | Phase 3 RCT | Double-blind | Obstructive HCM | 251 (123/128) | 30 weeks | Mavacamten oral | Doses starting from 5 mg up to 15 mg |

| Ho et al. 2020 [6] | MAVERICK-HCM | Multi-center, United States | Phase 2 RCT | Double-blind | Non-obstructive HCM | 59 (40/19) | 16 weeks | Mavacamten | Target serum concentrations of either 200 ng/mL or 500 ng/mL |

| Desai et al. 2022 [8] | VALOR-HCM | Multi-center, United States | Phase 3 RCT | Double-blind | Obstructive HCM | 112 (56/56) | 16 weeks | Mavacamten oral | 5 mg daily titrated up to 15 mg |

| Tian et al. 2023 [9] | EXPLORER-CN | Multi-center, China | Phase 3 RCT | Double-blind | Obstructive HCM | 81 (54/27) | 30 weeks | Mavacamten oral | Once daily with starting dose 2.5 mg up to 15 mg |

| Aficamten | |||||||||

| Maron et al. 2023 [11] | REDWOOD-HCM | Multi-national | Phase 2 RCT | Double-blind | Obstructive HCM | 41 (28/13) | 10 weeks | Aficamten | Ranging from 5 mg up to 15 mg in cohort 1 and from 10 to 30 mg in cohort 2 |

| Maron et al. 2024 [7] | SEQUOIA-HCM | Multi-national | Phase 3 RCT | Double-blind | Obstructive HCM | 282 (142/140) | 24 weeks | Aficamten | Once daily starting from 5 mg up to 20 mg |

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the included studies.

| Study ID | Trial | Gender (male %; intervention/placebo) | Mean age ± SD or median (IQR); (intervention/placebo) | Patients receiving background HCM therapy (intervention/placebo; number of patients) | NYHA class (intervention/placebo; number of patients) | Baseline resting LVOT gradient (mmHg; intervention/placebo), mean (SD) | Baseline LVEF (%);mean (SD);(intervention/placebo) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blocker | Calcium channel blocker | II | III | ||||||

| Mavacamten | |||||||||

| Olivotto et al. 2020 [10] | EXPLORER-HCM | 54/65 | 58.5 ± 12.2/58.5 ± 11.8 | 94/95 | 25/17 | 88/95 | 35/33 | 52 (29)/51 (32) | 74 (6)/74 (6) |

| Ho et al. 2020 [6] | MAVERICK-HCM | 47.5/31.6 | 54 ± 14.6/53.8 ± 18.2 | 25/12 | 10/3 | 33/13 | 7/6 | - | 68.7 (5.5)/66.4 (7.7) |

| Desai et al. 2022 [8] | VALOR-HCM | 51.8/50.0 | 59.8 ± 14.2/60.9 ± 10.5 | 26/25 | 7/10 | 4/4 | 52/52 | 51.2 (31.4)/46.3 (30.5) | 67.9 (3.7)/68.3 (3.2) |

| Tian et al. 2023 [9] | EXPLORER-CN | 75.9/63.0 | 52.4 ± 12.1/51.0 ± 11.8 | 48/24 | 4/2 | 44/18 | 10/9 | 74.6 (35.1)/73.4 (32.2) [peak resting LVOT gradient] | 77.8 (6.9)/77.0 (6.7) |

| Aficamten | |||||||||

| Maron et al. 2023 [11] | REDWOOD-HCM | 46/38 | 57 (26–33)/59 (53–64) [median (IQR)] | 21/11 | 7/2 | 17/11 | 11/2 | 53 (42–70)/71 (44–94) [median (IQR)] | 70 (65-79)/75 (69-75) [median (IQR)] |

| Maron et al. 2024 [7] | SEQUOIA-HCM | 60.6/57.9 | 59.2 ± 12.6/59.0 ± 13.3 | 86/87 | 45/36 | 108/106 | 34/33 | 54.8 (27.0)/55.3 (32.1) | 74.8 (5.5)/74.8 (6.3) |

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NYHA: New York Heart Association; IQR: inter-quartile range; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. -: data not available.

The Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool was used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. All six studies were found to have a low risk of bias (Figure S1).

Transitivity was assessed through potential effect modifiers, which showed largely comparable baseline characteristics across the included studies. Although one study, MAVERICK-HCM, had patients with non-obstructive HCM as compared to other studies with obstructive HCM, node-splitting analyses showed no inconsistency (Figures S2–4).

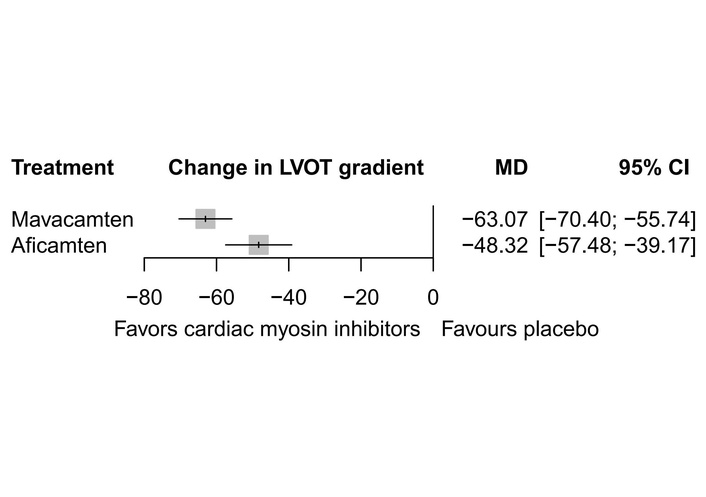

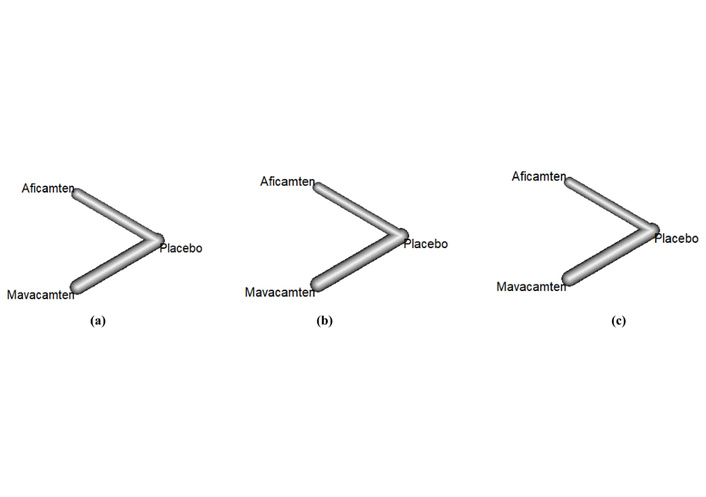

Five studies reported the data for this outcome. When compared with placebo, both mavacamten [MD = –63.07, 95% CI (–70.40; –55.74)] and aficamten [MD = –48.32, 95% CI (–57.48; –39.17)] caused a significant decrease in resting LVOT gradient. Heterogeneity across the included studies was found to be high (I2 = 90.2%) (Figure 2). The network graph is given in Figure 3. There were no RCTs comparing the effects of mavacamten with those of aficamten directly. Indirect comparison (Table 3) of aficamten versus mavacamten showed that aficamten caused a lesser decrease in LVOT gradient than that of mavacamten [MD = 14.74, 95% CI (3.02; 26.47)]. There was no inconsistency between study designs, indicating that the network meta-analysis results were reliable across the included designs. P-score ranking (Table 4) showed that mavacamten (0.9966) was higher in ranking than aficamten (0.5034) in reducing the resting LVOT gradient.

Forest plot showing change in resting LVOT gradient. LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; MD: mean difference.

Network graphs of (a) resting LVOT gradient, (b) NYHA class improvement, (c) change in LVEF; nodes represent the number of trials, and lines represent the effect sizes. LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; NYHA: New York Heart Association; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

Direct comparison of mavacamten versus placebo and aficamten versus placebo; and indirect comparison of aficamten versus mavacamten through a common comparator placebo.

| Direct evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | No. of studies | Pooled effect sizeMD [95% CI] |

| Change in resting LVOT gradient | Aficamten | Placebo | 2 | –48.32 [–57.48; –39.17] |

| Mavacamten | Placebo | 3 | –63.07 [–70.40; –55.74] | |

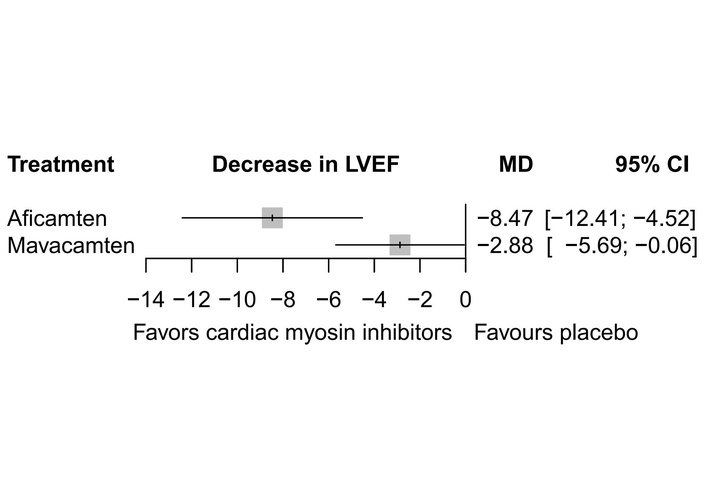

| Decrease in LVEF | Aficamten | Placebo | 2 | –8.47 [–12.41; –4.52] |

| Mavacamten | Placebo | 4 | –2.88 [–5.69; –0.06] | |

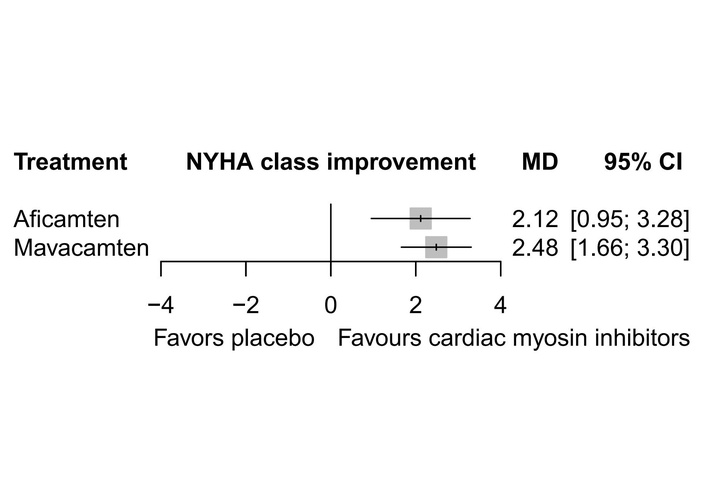

| NYHA class improvement | Aficamten | Placebo | 2 | 2.12 [0.95; 3.28] |

| Mavacamten | Placebo | 4 | 2.48 [1.66; 3.30] | |

| Indirect evidence | ||||

| Outcome | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Pooled effect size MD [95%CI] | Inconsistency tests (between designs)Q, df |

| Change in resting LVOT gradient | Aficamten | Mavacamten | 14.74 [3.02; 26.47] | 0.00 |

| Decrease in LVEF | Aficamten | Mavacamten | –5.59 [–10.43; –0.75] | 0.00 |

| NYHA class improvement | Aficamten | Mavacamten | –0.37 [–1.79; 1.06] | 0.00 |

MD: mean difference; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Treatment ranking through P-score.

| Treatment ranking (P-score) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in LVOT gradient | Decrease in LVEF | NYHA class improvement | |||

| P-score | P-score | P-score | |||

| Mavacamten | 0.9966 | Placebo | 0.9887 | Mavacamten | 0.8466 |

| Aficamten | 0.5034 | Mavacamten | 0.5053 | Aficamten | 0.6533 |

| Placebo | 0.0000 | Aficamten | 0.0059 | Placebo | 0.0001 |

LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

All six studies reported the data for the LVEF. Analysis indicated that both mavacamten [MD = –2.88, 95% CI (–5.69; –0.06)] and aficamten [MD = –8.47, 95% CI (–12.41; –4.52)] significantly decreased the LVEF. Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 96.8%) across the included studies (Figure 4). Indirect comparison through placebo (Figure 3) showed that aficamten caused a significant decrease in LVEF as compared to mavacamten [MD = –5.59, 95% CI (–10.43; –0.75)] (Table 3). Inconsistency between study designs was found to be zero. Mavacamten (0.5053) ranked superior to aficamten (0.0059), while placebo (0.9887) ranked the highest according to P-score ranking (Table 4) when a decrease in LVEF was considered as an adverse effect.

Forest plot showing change in LVEF. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MD: mean difference.

The data for NYHA class improvement were reported by all six studies. The meta-analysis showed that mavacamten [MD = 2.48, 95% CI (1.66; 3.30)] and aficamten [MD = 2.12, 95% CI (0.95; 3.28)] produced a significant change in the NYHA class improvement when compared to placebo with high heterogeneity (I2 = 87.6%) across the included studies (Figure 5). There was no statistically significant difference between the two drugs when compared indirectly (Figure 3) [MD = –0.37, 95% CI (–1.79; 1.06)] (Table 3). However, mavacamten (0.8466) ranked higher than aficamten (0.6533) through P-score ranking (Table 4). There was no evidence of inconsistency between study designs, indicating that the network meta-analysis results were reliable across the included designs.

Forest plot showing NYHA class improvement. NYHA: New York Heart Association; MD: mean difference.

This network meta-analysis compares the effectiveness and safety of two cardiac myosin inhibitors, mavacamten versus aficamten, utilizing six RCTs. Four of these trials (EXPLORER-HCM, MAVERICK-HCM, VALOR-HCM, EXPLORER-CN) compared mavacamten, and two (REDWOOD-HCM, SEQUOIA-HCM) compared aficamten to placebo. Through indirect comparison by a common comparator, i.e., placebo, this study shows that mavacamten is ranked higher than aficamten for HCM when change in resting LVOT gradient, NYHA class improvement, and change in LVEF are considered.

Left ventricle outflow obstruction is a strong predictor of progression to heart failure in HCM patients, with high resting LVOT gradient associated with increased risk of heart failure and death [21, 22]. The patients with severe obstruction may require invasive procedures like septal reduction surgery or myomectomy for relief [23]. Reduction in resting LVOT gradient can improve clinical outcomes and quality of life in patients with obstructive HCM [24]. Mavacamten and aficamten, while working on myosin cross-bridging and preventing force generation [25, 26], affect the hypertrophied myocardium on a molecular level [27]. They reduce cardiac contractility and provide relief of obstruction, holding a promising future in HCM management [28, 29].

With the exception of MAVERICK-HCM, which included patients with non-obstructive disease, all of the studies demonstrated improvement in resting LVOT gradient by both medications. However, mavacamten showed a stronger impact in improving the resting LVOT obstruction as shown by a higher P-score ranking of mavacamten (0.9966) as compared to that of aficamten (0.5034) achieved via indirect comparison of five of the six RCTs. There was no inconsistency between the study designs; however, the heterogeneity was high for direct comparisons, indicating differences in effect sizes that could be due to different study durations, populations, or drug dosages. The statistical significance of the decrease in LVOT gradient in HCM does not always translate into clinically significant effects; it varies according to the severity of symptoms. It holds significance in cases of mild symptoms but becomes less meaningful in cases of severe symptoms [30]. Hence, although the 14.7 mmHg greater reduction with mavacamten is statistically significant and directionally favorable, it is quite modest with respect to the major decision-making criteria that define the severity of obstruction. Even though it may contribute to gradual hemodynamic improvement, this difference may not consistently translate into a clinically noticeable benefit in every patient.

LVEF decreased in all six clinical trials that were analyzed. This is in line with findings of previous studies, which reported a transient decrease in LVEF [31]. Decrease in LVEF indicates a decline in systolic function, which can lead to serious complications of heart failure and is associated with higher mortality rates [32, 33]. It could be due to inhibition of contractile mechanics of sarcomere by these drugs [34]. In MAVERICK-HCM, five mavacamten subjects saw a reversible decrease in LVEF of less than 45%. However, VALOR-HCM revealed that changes in baseline systolic function linked to mavacamten were minimal, in contrast to the steep drop in LVOT gradients. The average decrease in LVEF was –3.9%, while the placebo caused a –0.01% decrease. In EXPLORER-HCM, seven patients on mavacamten (four patients at the end of treatment) developed an LVEF of less than 50%, indicating only slight decreases in mean global LV systolic function. Real-world data from the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program for mavacamten demonstrated that only 4.6% of the 5,573 patients experienced LVEF < 50% during a 22-month evaluation [35]. In the MAVA-LTE study, an EXPLORER extension cohort, 12 (5.2%) of 231 enrolled patients experienced a transient reduction in LVEF < 50% with mavacamten. However, these were reversible and treatment was resumed [36]. The LVEF of the aficamten group was marginally lower than that of the placebo group, per both aficamten trials, which could require monitoring. However, the FOREST-HCM study, a 36-week extension study of the REDWOOD cohort, demonstrated that most of the patients being treated with aficamten were able to maintain normal LVEF. Only 2 of the 34 non-obstructive HCM patients experienced LVEF < 50% for which they had to undergo dose adjustment, but the small sample size is the studyʼs limitation [37]. The reductions in LVEF were reversible with the changes in dose [38] and led to discontinuation rates ranging from 1.3% to 8% across studies [39]. Our investigation showed that mavacamten could be a better choice than aficamten since aficamten demonstrated a greater degree of reduction in LVEF, which is undesirable, as indicated by the P-score ranking of mavacamten (0.5053) and aficamten (0.0059).

Myosin inhibitors led to a considerable improvement in the NYHA class, a quality-of-life predictor in HCM patients [40]. Aficamten showed better early results at week 10 than mavacamten did at week 16, and all clinical studies revealed a reduction of at least one NYHA functional class in greater numbers when compared to placebo. Mavacamten demonstrated the greatest improvement of 37% in the EXPLORER-HCM cohort, whereas aficamten demonstrated this improvement in over 50% of the cohort in REDWOOD-HCM. However, no statistical difference was observed when they were compared to each other indirectly, yet P-score ranking showed that mavacamten was more effective. NYHA class improvement could predict the risk of hospitalizations and mortality [41, 42]. The high heterogeneity observed in the direct comparisons could be due to differences in dosage and follow-up durations. The research populations varied among trials based on HCM phenotype (obstructive vs. non-obstructive), baseline LVOT gradients, and background medical therapy, with MAVERICK-HCM enrolling only non-obstructive HCM and all other studies enrolling only obstructive illness. Drug exposure varied significantly, with mavacamten utilizing fixed or titrated low-dose regimens or target serum concentrations, and aficamten adopting broader, higher dose ranges over shorter titration intervals. The follow-up period spanned from 10 to 30 weeks, and outcome evaluation differed in terms of LVOT gradient reporting (mean vs. median; resting vs. peak), NYHA class distributions, and LVEF measurements, all of which contributed to heterogeneity. Also, these possible causes of heterogeneity were not systematically investigated via subgroup analyses or meta-regression owing to the limited number of included studies. As a result, these explanations continue to be hypothesis-generating, and the degree to which certain patient or therapy features alter treatment results remains yet to be assessed.

The distinct pharmacological profiles of mavacamten and aficamten should be taken into consideration while assessing the differences in their hemodynamic efficacy and reduction in LVEF. The extended half-life and prolonged exposure of mavacamten may result in notable and sustained decreases in LVOT gradients, but it also requires thorough dose titration and monitoring. Aficamten, on the other hand, has a shorter half-life and a quicker pharmacokinetic offset, which might allow for a wider dosage range as well as a quicker recovery of systolic function after dose modification or interruption.

These pharmacologic differences imply that future therapy choices could be tailored according to patient factors, such as comorbidities, relative sensitivity to negative inotropy, baseline LVOT obstruction, and the practicality of regular echocardiographic monitoring. Aficamten may eventually be taken into consideration in cases when quick titratability and reversibility are important, even though mavacamten may be preferred in patients needing prolonged gradient lowering. However, after regulatory approval, direct comparative trials and actual safety data would be necessary for drawing firm conclusions.

There are numerous strengths of this network meta-analysis. First, this study is the first to compare mavacamten with aficamten; no trial has yet compared these two drugs with each other. Second, the use of only RCTs enhances the strength of the evidence. Third, there was no inconsistency across the employed study designs, which adds to the credibility of the findings.

Notwithstanding its novelty, our research has a number of limitations. Inclusion of only six RCTs limits the data, excludes populations with distinct traits that could cause unpredictability, and makes it impossible to extrapolate our findings without additional proof from direct trials. These two medications are not compared directly in any of the included studies, which is a source of bias. Although the MAVERICK-HCM study differed in having patients with non-obstructive HCM compared to other studies with obstructive HCM patients, sensitivity analysis excluding this study was not performed. Compared to aficamten, mavacamten has an unfair advantage because of the increased number of clinical trials. Aficamten has a favorable profile and is promising as an alternative, but mavacamten has a greater body of clinical evidence proving its efficacy and safety, giving it a distinct edge in terms of dependability and clinical expertise; thus, it seems to have the advantage for the time being. Despite promising results, long-term safety and efficacy data are still needed, and further research is required to explore the potential of myosin inhibitors in modifying disease progression and their application in non-obstructive cardiomyopathy. Regulatory approval and additional clinical testing could make aficamten a viable choice for patients, and in the future, it may even outperform mavacamten due to its higher potency and longer half-life [43].

This network meta-analysis showed that mavacamten demonstrated greater efficacy than aficamten in indirect comparison, thus it ranked superior between the two myosin inhibitors to be used. However, this ranking is based not on the absolute clinical benefit but on the point estimates. Therefore, additional head-to-head trials comparing the two medications directly would be necessary to provide conclusive evidence that one is superior to the other. The final choice will probably rely on the patient, the severity of HCM, and the response to treatment, as both of these medications are valuable additions to the cardiology toolbox.

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

LV: left ventricular

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract

MD: mean difference

NYHA: New York Heart Association

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

RCT: randomized controlled trial

RR: risk ratio

SE: standard error

The supplementary tables and figures for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/101289_sup_1.pdf.

Pre-print: the pre-print is posted on SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5183557. Conference: the abstract of this manuscript was presented to the conference at the APPNA Spring Meeting 2025 and is published in the conference proceedings in Pakistan Heart Journal under the doi: https://pakheartjournal.com/index.php/pk/article/view/3065.

Ayesha A: Writing—original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. BA: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Arfa A: Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Software, Writing—original draft. MM: Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft. ET: Visualization, Software, Methodology, Writing—original draft. AH: Formal analysis, Software, Writing—review & editing. MZB: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. Aleena A: Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Visualization. SA: Writing—original draft, Software, Visualization. MWZK: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of this manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

All the data utilized in this study are available in the relevant figures and Tables S3–5.

This research did not receive any specific grant or funding from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1223

Download: 44

Times Cited: 0