Affiliation:

Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hamidiye Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul Haseki Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Istanbul 34265, Türkiye

Email: dr.enata@yahoo.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9997-9364

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101291 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101291

Received: November 13, 2025 Accepted: January 12, 2026 Published: February 2, 2026

Academic Editor: Adriana Coppola, Clinical Institute Beato Matteo, Italy

Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm is a rare acquired cardiac abnormality that frequently occurs after myocardial infarction or a previous cardiac procedure. Blunt chest trauma accounts for this uncommon entity in sporadic cases. However, this disease does not have any specific clinical findings, so it is necessary to monitor the suspected patient closely. The standard noninvasive techniques for diagnosing left ventricular pseudoaneurysms are transthoracic echocardiography and thoracic computed tomography. Untreated ventricular pseudoaneurysms carry a considerable risk of rupture, ranging from 30% to 45%. So, an urgent surgical treatment is often required. Herein, we aimed to present a 34-year-old male who underwent emergency surgery as a result of cardiac perforation three hours after a traffic accident and developed a giant left ventricular pseudoaneurysm 19 months after discharge. The giant pseudoaneurysm was successfully repaired. This case highlights the need for long‑term surveillance after blunt cardiac trauma to detect late pseudoaneurysm formation.

Left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysms (also known as “false aneurysms”) are defined as outpouchings created when cardiac rupture is contained by overlying adherent pericardium and thrombotic material, with no myocardial tissue [1]. This clinical condition is more prone to rupture, so it often requires emergency surgery [2, 3]. According to the available data from case reports and case series, the most common etiology of LV pseudoaneurysms is myocardial infarction, accounting for 55% of the cases. One-third of pseudoaneurysms arise after a surgical procedure, most commonly mitral valve replacement. It is reported that only 7% of these diseases are caused by penetrating and blunt trauma [4, 5]. In the majority of cases, there are no specific findings of this disease; the diagnosis should generally be based on radiological imaging or clinical suspicion. Herein, we presented a patient who underwent emergency operation as a result of right ventricular (RV) perforation after a car accident, and undergone second operation due to the development of a giant posterior LV pseudoaneurysm 19 months after discharge.

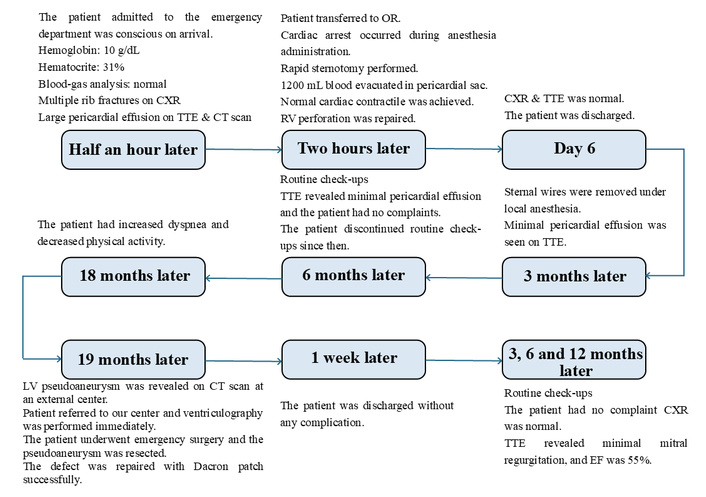

A 34-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department approximately 30 min following a high-velocity motor vehicle collision. After two hours, the patient was brought to the operating room (OR) due to cardiac injury and cardiac tamponade. The patient successfully underwent RV perforation repair surgery and was discharged on the 6th postoperative day without any complications. Three months later, three of the upper sternal wires were removed under local anesthesia. Nineteen months later, the patient was urgently admitted to our center from a rural hospital after being diagnosed with a giant LV pseudoaneurysm. The patient underwent redo emergency surgery and was discharged on the 7th postoperative day following a successful LV pseudoaneurysm repair operation (Figure 1).

Timeline events and the treatment details are in chronological order. CT: computed tomography; CXR: chest X-ray; LV: left ventricular; OR: operating room; RV: right ventricular; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography.

The initial mechanism of injury involved a frontal impact with a parked vehicle, resulting in blunt chest trauma. The patient reported no significant past medical history. He was conscious, and vital signs were normal on arrival. Diminished heart sound and left-sided multiple rib friction were revealed on physical examination. Arterial blood-gas analysis was within the normal range. Hemoglobin and hematocrite was 10 g/dL and 31%. Cardiac arrest occurred while the patient was being transferred to the operating table due to cardiac tamponade. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, and rapid sternotomy was performed. After 1,200 mL of blood was evacuated from the pericardial sac, the cardiac function returned to normal. A nearly 2 cm perforation was seen on the anterior RV with continuous bleeding. This injury was repaired with 4/0 teflon reinforced polypropylene sutures when the heart was beating. No other cardiac abnormalities were detected, and the surgery was terminated. Eighteen months later, the patient began to experience a gradual worsening of dyspnea and chest pain, corresponding with a progressive decline in physical activity. The following month, the patient was diagnosed with a LV pseudoaneurysm at the hospital he visited. The patient was readmitted to our center, and after the diagnosis was confirmed, an emergency surgery was scheduled. Given the high risk of catastrophic rupture and to mitigate the risk of re-entry injury, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was prudently instituted via peripheral cannulation prior to performing the median sternotomy. The operation commenced with careful dissection of dense pericardial adhesions. Upon incision of the aneurysm sac, no organized thrombus was found within the cavity. The pseudoaneurysm neck, estimated at 2.5 cm in diameter, was identified and closed using a 5 × 5 cm circular Dacron patch. The repair was then reinforced by suturing the overlying native pericardial tissue onto the Dacron patch. Aortic cross clamp and CPB time were 27 min and 45 min, respectively.

Cardiac enlargement and fractured left 2nd, 3rd, and 5th ribs were the important findings of chest X-ray (CXR) at first admission (Figure 2). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and thoracic computed tomography (CT) confirmed a massive pericardial effusion (Figure 3). Cardiac valvular functions were normal. All of this indicated significant cardiac injury and ongoing cardiac tamponade. The diagnosis was confirmed once the pericardial cavity was accessed.

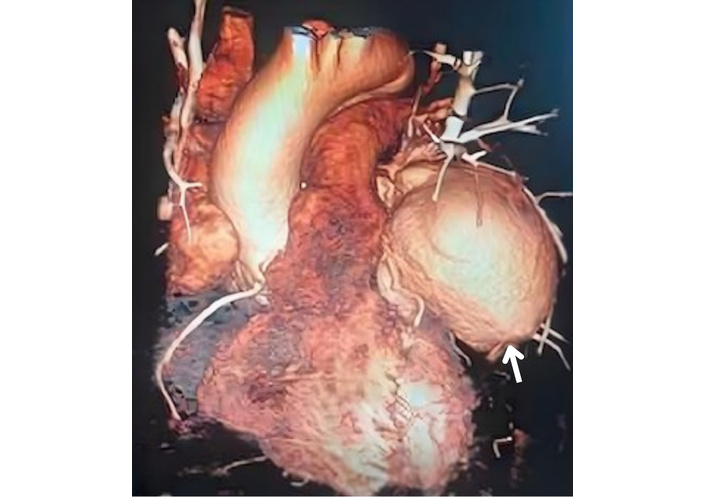

A TTE evaluation performed three months later did not report the mass seen on CXR as a possible pseudoaneurysm (Figure 4). The mass on the left side became more prominent on CXR (Figure 5), nineteen months later. A thoracic CT scan revealed a giant pseudoaneurysm on the posterior wall of LV which was 10 cm × 7 cm in size (Figure 6). The patient was urgently transferred to our center for definitive management, where a coronary angiography (CA) was performed. CA showed normal coronary anatomy (Figures 7 and 8), but left ventriculography confirmed the diagnosis: leakage of contrast medium into the pseudoaneurysm sac was clearly observed (Figures 9 and 10).

Thoracic CT imaging shows a left ventricular pseudoaneurysm (arrow). CT: computed tomography.

The patient’s recovery was uncomplicated, leading to discharge on the 7th postoperative day. The patient underwent serial TTE evaluations at 3, 6, and 12 months post-discharge. The TTE data confirmed preserved cardiac contractility (LV ejection fraction [LVEF] of 55%) and a complete absence of effusion or significant valvular dysfunction throughout the first year of surveillance.

LV pseudoaneurysms are uncommon cardiac pathologies that typically require surgical repair. Most cases of LV pseudoaneurysm may have a previous myocardial infarction and/or cardiac surgery [5, 6]. Less commonly, cardiac pseudoaneurysms occur after other clinical conditions, such as penetrating or blunt chest trauma and infections, as reported in a comprehensive systematic review [4]. Congestive heart failure, non-specific symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea were the most frequent findings [5]. However, most of these signs are not useful in early diagnosis, as they can be seen in the advanced stages of the disease. Although radiographic findings are usually nonspecific, the appearance of a mass is present in more than half of patients [1]. In this case, we believe that the delayed posterior LV pseudoaneurysm resulted from posterior endomyocardial damage caused by initial severe blunt trauma. Although the entire heart was carefully examined after the RV injury was repaired, the posterior location and contained nature of the LV injury likely rendered it visually inapparent and subsequently clinically silent.

In a retrospective analysis of this case, the mass on the left side, seen on a CXR taken three months later, was not detected by TTE (Figure 4). Although TTEs are often the first test performed due to their widespread availability and routine use in the initial evaluation of patients, they have low sensitivity in detecting pseudoaneurysms. It is a fact that the more posterior the aneurysm, the more difficult its detection by TTE [7]. In this case, the absence of symptoms and the lack of a prior myocardial infarction were also significant factors in not raising sufficient suspicion for diagnosis. We believe that the severe pericardial adhesions associated with the initial surgery prevented the rapid progression and rupture of the pseudoaneurysm.

Ventricular angiography has been traditionally considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms. Currently, this diagnostic technique is only applied in a limited number of cases due to its time-consuming nature and the risk of pseudoaneurysm rupture [8]. In this case, besides showing normal coronary anatomy, it also allowed us to clearly measure the pseudoaneurysm size and provided information about the complete filling of the sac and the absence of thrombi. Cardiac CT or magnetic resonance image (MRI) is also the most definitive test, and the information they provide is essential for early diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning [9, 10].

There are a few reports in the literature regarding pseudoaneurysms due to blunt trauma, and a definitive treatment guideline has not yet been established. The first successful surgical repair of a ventricular pseudoaneurysm was performed by Smith et al. [11] in 1957. Since then, surgical repair has been the preferred treatment for LV pseudoaneurysms. Moreno et al. [12] reported a cumulative survival of 74.1% at 4 years for chronic pseudoaneurysms treated medically. However, surgery has been associated with a lower in-hospital mortality compared to conservative treatment. Percutaneous closure techniques with the septal occluder device and coils in high surgical risk patients have been successful in different centers since the early 2000s [13, 14]. Nevertheless, these methods have technical challenges, and their long-term outcomes are uncertain.

Recent advances in cardiac reoperation techniques have appeared to further decrease the perioperative mortality to less than 10% [15]. We preferred peripheral cannulation in the surgical approach of this case for two reasons: firstly, challenging central access and avoiding re-entry injury; secondly, avoiding sudden rupture of the pseudoaneurysm at the time of sternotomy. We initiated CPB rapidly via the femoral vessels and decompressed the heart prior to the sternotomy. This allowed us to commence the operation uneventfully. Following resection of the pseudoaneurysm sac, the resulting defect was repaired using a tailored Dacron patch. The entire operation and post-operative follow-up were completed without any complications.

Blunt cardiac trauma requires long‑term surveillance. Due to limitations in detecting posterior pseudoaneurysms, TTE may not be a reliable tool for possible diagnosis. Therefore, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI should be considered for definitive diagnosis. Left ventriculography can be extremely useful in both diagnosis and surgical planning.

CA: coronary angiography

CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass

CT: computed tomography

CXR: chest X-ray

LV: left ventricular

MRI: magnetic resonance image

RV: right ventricular

TTE: transthoracic echocardiography

ECA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Validation. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was waived because, according to the local ethics committee, ethical review for the investigation carried out before the year 2020 was not required.

An informed consent form was signed by the participant.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from the participant.

All the information about the patient is available from the electronic medical record system. The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 264

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0