Affiliation:

1Internal Medicine, Baptist Memorial Hospital North Mississippi, Oxford, MS 38655, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7553-8650

Affiliation:

2Internal Medicine, King Edward Medical University, Lahore 54000, Pakistan

Email: frajab258@gmail.com

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101285 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101285

Received: August 27, 2025 Accepted: November 27, 2025 Published: January 05, 2026

Academic Editor: Dmitry Duplyakov, Samara State Medical University, Russian Federation

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third most common cause of cardiovascular mortality and presents a significant challenge in acute care settings. EkoSonic Endovascular System (EKOS) (ultrasound assisted catheter directed thrombolysis) and suction thrombectomy have emerged as key treatment options for high and intermediate risk PE. EKOS delivers localized fibrinolytic therapy, whereas thrombectomy provides definitive clot removal using devices such as the FlowTriever System (Inari Medical). However, the optimal treatment strategy, particularly in recurrent PE, remains uncertain. We report a case requiring escalation of therapy from EKOS to suction thrombectomy due to recurrent PE and worsening hemodynamic status despite initial thrombolysis. The patient was initially treated with EKOS for a saddle PE but was rehospitalized with syncope and persistent right ventricular (RV) strain. Given the inadequate response to thrombolysis, suction thrombectomy was performed, leading to marked improvement in RV function and overall clinical status. This case underscores the importance of individualized management and timely escalation when initial therapy is insufficient. Assessment of therapeutic success should include not only symptomatic relief but also resolution of clot burden and RV recovery. A focused literature review comparing EKOS and suction thrombectomy suggests that while both modalities are viable, suction thrombectomy may offer faster hemodynamic improvement in select patients. However, available data remains limited, highlighting the need for further comparative studies. Overall, this case and review support a tailored, multidisciplinary approach to PE management, emphasizing shared decision making and early escalation in patients with clinical deterioration despite initial intervention.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening condition that occurs when a blood clot originating from another part of the body, most commonly from the deep veins of the legs, obstructs the pulmonary arteries. This leads to dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, syncope, hemodynamic instability, right ventricular (RV) failure, and, in severe cases, cardiac arrest. The presence of hemodynamic instability is crucial for classifying PE and identifying high-risk PE. Patients with systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg for more than 15 min in the absence of hypovolemia, sepsis, or arrhythmia, and those requiring inotropes or vasopressors to maintain hemodynamic stability are considered to have massive or high-risk PE with an increased likelihood of death from obstructive shock [1].

Acute PE has a higher incidence in males compared with females [2] and carries a high mortality rate, causing approximately 100,000 deaths annually in the United States [2, 3]. It is the third leading cause of cardiovascular-related death in the country [4]. Acute massive PE can result in RV failure; therefore, it is crucial for clinicians to identify impending RV strain and shock in patients with PE who develop bradycardia or a new broad complex tachycardia with right bundle branch block [2, 5].

PE can be classified into five risk categories using the PE severity index (PESI) score, which is based on 11 clinical variables that estimate 30-day mortality and guide management. According to this scoring system, patients identified as very low or low risk may be appropriate for outpatient treatment or early discharge with oral anticoagulants [6–9], whereas those at intermediate or high risk can benefit from endovascular therapies in conjunction with medical therapy [10].

In the past, patients with PE were commonly treated with systemic thrombolysis; however, this approach is associated with an increased risk of bleeding [11]. Consequently, endovascular treatment modalities are becoming increasingly popular and are broadly classified into mechanical thrombectomy and catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) [12].

One example of CDT is the EkoSonic Endovascular System (EKOS), which treats PE using small catheters placed in the pulmonary arteries through a vein. It delivers ultrasound waves that enhance the binding of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to the clot, accelerating thrombolysis. Mechanical thrombectomy devices include the FlowTriever System (Inari Medical), Indigo Thrombectomy System (Penumbra, Inc.), and AngioVac or AlphaVac (Angiodynamics, Inc.) [12].

Our case report and literature review demonstrate the value of escalating management from EKOS to thrombectomy for persistent clot burden following initial thrombolysis, supported by a brief review of published case reports on both modalities.

Timeline mentioned in Table 1.

Timeline.

| Hospitalization order | Day | Events |

|---|---|---|

| First hospitalization | Day 1 | Presented with shortness of breath, palpitations, and syncope. CTA showed a large saddle PE with right heart strain. Started on heparin infusion. |

| Day 2 | Underwent catheter-directed thrombolysis (EKOS). Symptoms and tachycardia improved. Transitioned to apixaban. | |

| Day 4 | Echo showed improving RV function and continued physical therapy. | |

| Day 5 | Discharged on apixaban (3 months) and home oxygen (2 L/min). | |

| Second hospitalization | Day 1 | Readmitted the very next day with recurrent syncope. CTA showed a persistent clot burden with right heart strain. Restarted on heparin. |

| Day 2 | Echo showed McConnell’s sign. Underwent INARI thrombectomy. Transferred to ICU. | |

| Day 3 | Marked improvement; tachycardia and dyspnea resolved. | |

| Day 4 | Stable; cardiology signed off. | |

| Day 5 | Discharged on apixaban and scheduled for outpatient follow-up. |

CTA: computed tomography angiography; EKOS: EkoSonic Endovascular System; PE: pulmonary embolism; RV: right ventricular; ICU: intensive care unit.

A 49-year-old female with class III obesity and a history of recent left ankle surgery three weeks prior presented with acute shortness of breath, palpitations, and a syncopal episode while ambulating. She had been non-weight-bearing in a cast and reported new-onset left lower extremity pain four days earlier, which she initially attributed to cramping from immobility. On examination, the patient was tachycardic, hypotensive, afebrile, and tachypneic. She appeared acutely ill and diaphoretic, with cool, clammy skin, weak peripheral pulses, and delayed capillary refill. Breath sounds were clear bilaterally.

Initial labs were performed. The chest X-ray was unremarkable, and the electrocardiogram (EKG) showed an S1Q3T3 pattern, raising suspicion for PE. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) confirmed a large saddle embolus with extensive bilateral clot burden and right heart strain. After EKOS therapy, a limited echocardiogram showed improved but persistent RV dilation. During her second hospitalization, labs showed pro-BNP 3,554 pg/mL and troponin 30 ng/L. Repeat CTA revealed residual thrombus with right heart strain (RV to left ventricular, RV/LV 1.15) and McConnell’s sign on echocardiography. Her PESI score was 90 points, corresponding to intermediate risk (Class III) and a 30-day mortality risk of 3.2–7.1%, guiding the decision for further intervention.

The patient was initiated on an intravenous heparin bolus followed by continuous infusion. Due to the extensive clot burden and hemodynamic instability, interventional cardiology was consulted, and she underwent CDT (EKOS). Systemic thrombolysis was deferred after shared decision-making because of increased bleeding risk. The patient’s symptoms improved markedly, and her tachycardia resolved shortly after the procedure. She transitioned to oral apixaban (Eliquis) for continued anticoagulation. Follow-up echocardiography demonstrated improved RV function, and she continued to recover with physical therapy support. She was discharged on a three-month course of apixaban and home oxygen (2 L/min) for persistent hypoxia.

During her second hospitalization, intravenous heparin was restarted after imaging confirmed residual thrombus. Following multidisciplinary discussion and informed consent, she underwent INARI mechanical thrombectomy, during which a large thrombus was successfully extracted (Figure 1). Post-procedure, she was monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU), showing rapid clinical improvement with resolution of tachycardia and dyspnea. On day five, she was discharged on apixaban for three months and arranged for outpatient cardiology follow-up.

After discharge from her second hospitalization, the patient experienced no unanticipated events or complications. She achieved full clinical recovery with complete resolution of her symptoms. On follow-up visits with her primary care physician at one week and two months, she reported no dyspnea, palpitations, or functional limitations and remained hemodynamically stable.

Initial laboratory values are summarized in Table 2. The chest X-ray was unremarkable. The EKG demonstrated an S1Q3T3 pattern, raising suspicion for PE. CTA confirmed a large saddle PE with extensive clot burden involving the bilateral lobar pulmonary arteries, accompanied by signs of right heart strain, including septal straightening and an elevated RV/LV ratio. Following treatment with CDT (EKOS), a limited echocardiogram performed on day four continued to show evidence of right heart strain but with improved RV size and function, consistent with partial recovery.

Laboratory values at admission.

| Laboratory parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Lactic acid | 2.6 mmol/L |

| Anion gap | 14 mEq/L |

| White blood cells | 10.1 × 103/μL |

| Troponin | 159–221 ng/L |

| Pro-BNP | 438 pg/mL |

| pH | 7.44 |

| pCO2 | 34 mmHg |

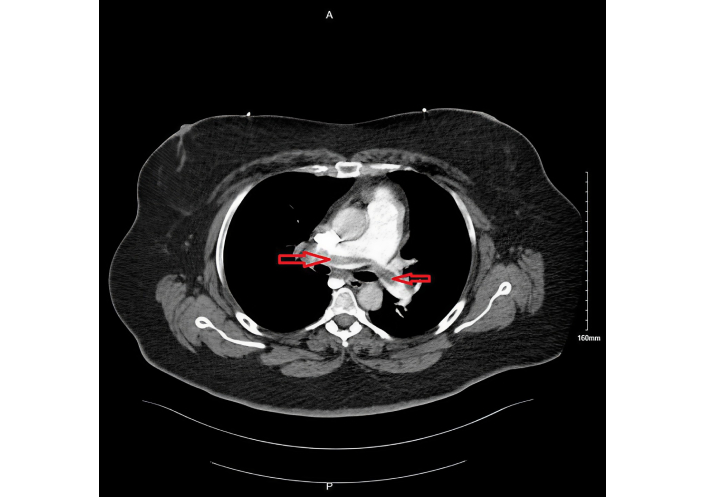

During her second hospitalization, pertinent laboratory findings included a pro-BNP of 3,554 pg/mL and troponin of 30 ng/L. Repeat CTA (Figure 2) again revealed persistent thrombus within the segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries, with right heart strain evidenced by right atrial and ventricular enlargement and an RV/LV ratio of 1.15. A limited echocardiogram demonstrated McConnell’s sign with dilated right-sided chambers, confirming ongoing right heart strain. Her PESI score was 90 points, corresponding to intermediate risk (Class III) with an estimated 30-day mortality risk of 3.2–7.1%, which guided the decision for further intervention.

Persistent pulmonary embolism during 2nd hospitalization, seen on computed tomography angiogram as filling defect (shown by red arrows).

The patient expressed satisfaction with her care and overall outcome, noting significant improvement in her symptoms.

We present 17 case reports on EKOS and 16 case reports on INARI thrombectomy for the removal of clot burden in patients with PE, as part of a comprehensive literature review. This compilation allows for a clearer understanding of the applications of these interventions. By systematically listing indications and outcomes, this review aims to identify patterns in patient selection, efficacy, and safety, thereby assisting in refining clinical decision-making in the management of PE.

In patients who were treated with EKOS, the age ranged from 38 to 86 years, as shown in Table 3. This review highlights the efficacy of EKOS as a treatment modality. The majority of studies demonstrated a decrease or resolution of clot burden, a reduction in RV pressure with improvement in the RV/LV ratio, and subsequent recovery of RV function [13–22]. Das Gupta et al. [17] describe a case series in which EKOS was discontinued in all patients within 24 to 30 hours, and the patients were discharged within 24 hours after undergoing the procedure.

Summary of case reports and studies where EKOS was used to treat pulmonary embolism.

| Study | Patient characteristics | Parameters of right heart strain | Unique features of the case | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stambo and Montague [13] | 63/M | Echo revealed RVH with an RVP of 46 mmHg | IV tPA was administered before EKOS/tPA combination | Complete resolution of clot burden with EKOS/tPA combination |

| Bethea et al. [14] | 76/F | RVP 64/8 mmHg | Patient developed HIT after initially coagulation. Later, as she became dyspneic, CTA was repeated, which showed increased clot size and RV dilation. Then EKOS/tPA was done | Pulmonary artery pressure improved to 38/17 mmHg from 58/19 mmHg |

| Khan and Besis [23] | 74/M | RV/LV ratio 1.5/1 | JAK2 kinase +ve in patient | Patient went from requiring 15 L supplemental O2 to maintaining his sats > 90s on room air |

| Cetingok et al. [15] | 49/M | RV/LV ratio 1.1 | Post COVID hypercoagulability | Pulmonary angiography showed complete resolution of the clot burden 18 h after the procedure |

| Rahman et al. [16] | 41/M | RV/LV ratio 1.5 | Patient had Prader-Willi syndrome | Recovery from all symptoms after EKOS/tPA combination |

| Das Gupta et al. [17] | 52/M | RV/LV ratio 1.8 | Post procedural RV/LV ratio 0.87 and RV function was normal | |

| Das Gupta et al. [17] | 62/F | RV/LV ratio 1.6 | Post procedural RV/LV ratio 0.75 and RV function was normal | |

| Das Gupta et al. [17] | 38/F | RV/LV ratio 1.5 | Post procedural RV/LV ratio 0.91 and RV function was normal | |

| Das Gupta et al. [17] | 47/M | RV/LV ratio 1.5 | Post procedural RV/LV ratio of 1 and RV function was normal | |

| Das Gupta et al. [17] | 54/M | RV/LV ratio 1.4 | Post procedural RV/LV ratio of 1 and RV function was mildly reduced | |

| Tirthani et al. [24] | 71/M | The echo showed RV hypokinesis and a flattened interventricular septum | This case demonstrates EKOS’s failure to resolve the clot burden, leading to the use of systemic thrombolysis as a rescue therapy | The patient’s FiO2 showed modest improvement post EKOS and repeated CTA showed persistent right heart strain with minimal improvement in clot burden |

| Ganatra et al. [25] | 86/F | McConnell’s sign of echo | Intracranial hemorrhage after getting treated with EKOS-directed thrombolysis | Left parietal hemorrhage occurred 10 h later, leading to the cessation of tPA and heparin infusion and ultimately death 2 days later |

| Lochan and Raya [18] | 40/M | Enlarged right ventricle on echo | Pulmonary artery pressure decreased from 96/32 mmHg to 47/27mmHg | |

| James et al. [19] | 69/F | McConnell’s sign on echo | Repeat echo post procedure showed a decrease in RV size and improved function | |

| Lauren Lindsey et al. [20] | 38/M | Severely reduced RV systolic function on echo | Severe coagulopathy and development of hemorrhagic intracranial infarcts and hemothoraxUse of VA and VV ECMO | Repeat TTE showed significant improvement in both LV and RV functions |

| Ozturk and Dumantepe [21] | 81/F | Enlarged right ventricle on Echo | PA pressure decreased from 45 mmHg to 30 mmHg | |

| Shammas et al. [22] | 69/F | RV size 3.6 cm | A repeat CTA indicated a reduction in clot burden in the pulmonary artery. Repeat echo showed RV size of 3.1 cm and PA pressure of 44 mmHg (compared to initial 48 mmHg) |

CTA: computed tomography angiography; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EKOS: EkoSonic Endovascular System; RV: right ventricular; LV: left ventricular; RV/LV: RV to LV; tPA: tissue plasminogen activator.

The most common complication of EKOS was bleeding, as seen in case reports published by Ganatra et al. [25] and Lauren Lindsey et al. [20]. EKOS failure was observed in a case report by Tirthani et al. [24], where the patient was subsequently treated with systemic thrombolysis. Lauren Lindsey et al. [20] and Patel et al. [26] shed light on the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) via extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for stabilizing and supporting patients hemodynamically.

This review also provides insight into less common causes of PE successfully treated with EKOS. The patient described by Cetingok et al. [15] had a prior COVID infection and subsequently developed PE and superior mesenteric artery thrombosis about two months later, highlighting a post COVID thrombotic state as the likely culprit. Khan and Besis [23] documented a case of PE treated with EKOS in a patient with JAK2 kinase positivity, while Rahman et al. [16] reported a case involving a patient with Prader-Willi syndrome. According to the latter, there is a higher prevalence of PE in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome.

The patients treated with INARI had an age range from 32 to 88 years, as shown in Table 4. The majority of cases demonstrated a reduction in pulmonary arterial pressure, improvement in RV function, and resolution of clot burden following the procedure, highlighting the efficacy of INARI as a treatment modality [26–38]. None of the studies reported procedural failure.

Summary of case reports and studies where the INARI technique was used to treat PE.

| Study | Patient characteristics | Parameters of right heart strain | Unique features of the case | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [26] | 63/M | RV/LV 2.7 | Systemic thrombolysis was contraindicated and the patient was stabilized with VA ECMO | Restoration of pulmonary artery segmental and subsegmental flow post procedure. A retrievable IVC filter was inserted |

| Bayona Molano et al. [27] | 53/M | NT-proBNP levels were 832 pg/mLPA pressure was 38 mmHg | Systemic thrombolysis was contraindicated due to recent brain surgeryPE was a thrombus in transit involving RA and PA | Decreased clot burden in the RA and PA with no evidence of right heart strain. PA pressure on post procedure echo was 14 mmHg |

| Patel et al. [28] | 59/M | Straightening of the interventricular septum and clockwise rotation of the cardiac apex are seen on CTATroponins 89.9 pg/mL | Thrombus in transit with thrombus migration from right ventricle to pulmonary arteries | Significantly reduced clot burden post procedure |

| Garza et al. [29] | 57/M | Troponin 509 pg/mL and right ventricle dilation on echo. Pulmonary artery pressure was 38 mmHg | Pulmonary artery pressure reduced to 29 mmHg post procedure | |

| Jones et al. [30] | 76/M | RV systolic pressure was 80–85 mmHg | Fibroelastoma mass disguised as a clot | RV systolic pressure was reduced to 40–45 mmHg post procedure |

| Agarwal et al. [31] | 51/F | Troponins 58 pg/mL. RV/LV 1.33. Right ventricle systolic pressure 45 mmHg | INARI and Impella were done in a single session as signs of RV failure led to the placement of Impella RP | Significant improvement in hemodynamic parameters in a week |

| Nezami et al. [32] | 88/F | Troponin 91 pg/mL | Large clot burden in RA, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery | Pulmonary artery pressure decreased from 46/13 mmHg to 28/9 mmHg |

| Saricilar et al. [33] | 82/F | Right ventricle systolic pressure 45 mmHg | Fat embolism in transit | Post op right ventricle pressure was 31 mmHg |

| Stadler et al. [34] | 55/F | End diastolic mid diameter of the right ventricle was 53 mmRV dilation on TTE | First case of PE with acute right heart failure, treated with thrombectomy outside the USAVA ECMO was also implanted | The end diastolic mid diameter of the RV was 36 mm post procedure |

| Mathbout et al. [35] | 37/M | RA pressure 12 mmHgElevated troponin | The second episode is most likely due to immobilization during long periods of driving | Post procedural CTA showed no clot burden and near restoration of pulmonary artery blood flowPulmonary artery pressure decreased from 80/40 mmHg to 55/18 mmHg |

| Mathbout et al. [35] | 79/M | The interventricular septum flattened and bent to the left, with an RV/LV ratio of about 1.68:1RV pressure 60/10 mmHg | The PA pressure improved to 50/10 mmHg from 60/20 mmHg with full recovery of blood flow to both sides of the lungs | |

| Mathbout et al. [35] | 48/F | RV pressure 50/6 mmHg | Recent prior hospitalization secondary to COVID-19 | Post procedure, PA pressure 30/12 mmHg from 50/24 mmHg |

| Pham et al. [36] | 62/F | Chest CT showed right heart strain | Thrombus in transit, extending from the RA to the RV outflow tractAn initial moderate clot was removed, but the remaining clot was pushed into the RV outflow tract and could not be extracted from the PA despite repeated suction attempts | PA pressure decreased from 48/18 mmHg to 40/10 mmHg |

| Pham et al. [36] | 78/F | Right heart strain seen on chest CT | Pulmonary artery pressure decreased from 41/21 mmHg to 32/20 mmHg | |

| Capanegro et al. [37] | 75/M | Right heart strain evident on chest CT and echo | Mean pulmonary artery pressure decreased from 18 mmHg to 12 mmHg | |

| Mahmudlu et al. [38] | 32/F | McConnell’s sign is present | VA ECMO assist was taken | Pulmonary artery pressure decreased from 72 mmHg to 30 mmHg |

CTA: computed tomography angiography; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PE: pulmonary embolism; RV: right ventricular; RV/LV: RV to left ventricular; RA: right atrium.

This review also highlights the use of different types of MCS with INARI. MCS support with ECMO was utilized in the case reports provided by Patel et al. [26], Stadler et al. [34], Pham et al. [36], and Mahmudlu et al. [38], whereas Agarwal et al. [31] described a case in which MCS was established using the Impella device.

Several rare and unique cases were also reported. Jones et al. [30] described a distinctive case where a suspected clot within the pulmonary vasculature was later identified as a fibroelastoma. Saricilar et al. [33] reported a patient who developed fat embolism during right hip arthroplasty, in whom CT pulmonary angiography demonstrated multiple fat attenuation filling defects. Pham et al. [36] described a case in which tPA was injected into the right pulmonary artery because the clot size was too large to be aspirated. Stadler et al. [34] described the first reported case of PE with acute heart failure treated with INARI outside the United States.

Several studies have compared the two treatment modalities. A meta-analysis that examined 55 studies by Choksi et al. [39] (2025) concluded that both procedures achieved comparable clinical outcomes, with a greater improvement in the Miller index, RV/LV ratio, and pulmonary artery pressure among patients treated with ultrasound accelerated thrombolysis. In contrast, lower mean blood loss and shorter ICU and hospital stays favored mechanical thrombectomy [39]. However, thrombectomy was associated with longer procedural times compared with ultrasound assisted thrombolysis (USAT) [39, 40].

Multiple studies have reported similar safety outcomes, with no statistically significant differences in mortality rates between the two groups [40–42]. In contrast, Graif et al. [43] (2020) reported higher mortality rates in patients who underwent thrombectomy. A randomized controlled trial conducted in 2024, known as the PEERLESS trial [44], found large bore mechanical thrombectomy to be more effective than catheter directed thrombolysis (for example, EKOS) in acute intermediate risk PE. Thrombectomy was associated with fewer clinical deteriorations, reduced ICU utilization, improved respiratory and RV function, shorter hospital stays, and fewer readmissions. Mortality and bleeding rates, however, were similar between the two treatment strategies. Nevertheless, the available data remain insufficient to definitively determine the superiority of one procedure over the other.

Our case demonstrated the use of both treatment modalities in a sequential manner. EKOS resulted in improvement of RV function, consistent with the majority of previously published studies; however, it failed to achieve complete resolution of the clot burden in this patient. This resulted in clinical deterioration due to recurrent PE, for which mechanical thrombectomy was subsequently performed. These findings suggest that, in addition to improvements in RV function and symptoms, assessment of clot burden resolution is essential in high-risk cases such as saddle PE. Residual thrombus may predispose to recurrence of PE, particularly in patients who may perceive themselves as treated and disregard subsequent symptoms. This could lead to right heart failure or even a fatal event, underscoring the importance of close follow-up and vigilant monitoring in these patients.

Furthermore, this case highlights the potential benefit of employing dual treatment modalities or escalating therapy when one approach does not achieve adequate clot resolution. The findings suggest a possible role for INARI aspiration thrombectomy in cases where EKOS has not fully resolved the clot burden or adequately managed the condition, offering an additional therapeutic strategy to improve patient outcomes.

This case highlights the importance of individualized escalation in PE management when initial thrombolysis fails. Suction thrombectomy can provide rapid hemodynamic improvement and RV recovery. Equally crucial is post-procedure imaging to confirm clot resolution, assess RV function, and guide anticoagulation and follow-up strategies for optimal long-term outcomes.

CDT: catheter-directed thrombolysis

CTA: computed tomography angiography

ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

EKG: electrocardiogram

EKOS: EkoSonic Endovascular System

ICU: intensive care unit

MCS: mechanical circulatory support

PE: pulmonary embolism

PESI: pulmonary embolism severity index

RA: right atrium

RV/LV: right ventricular to left ventricular

RV: right ventricular

tPA: tissue plasminogen activator

USAT: ultrasound assisted thrombolysis

AJ: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. FR: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AI: Writing—review & editing. EM: Writing—review & editing. AM: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AR: Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The study was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional ethics committee of Baptist Memorial Hospital confirmed that formal approval was not required for this retrospective case report.

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the patient.

Informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

The data supporting this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (frajab258@gmail.com).

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1008

Download: 66

Times Cited: 0