Affiliation:

1Cardiovascular Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166615573, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4492-637X

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, Advanced Cardiac Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh 160012, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5433-0433

Affiliation:

3Department of Internal Medicine, Michigan State University at Hurley Medical Center, Flint, MI 48503, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5317-3357

Affiliation:

4Department of Cardiology, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital (DMCH), Ludhiana 141001, Punjab, India

Email: akashbatta02@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7606-5826

Affiliation:

1Cardiovascular Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166615573, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9577-0099

Affiliation:

4Department of Cardiology, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital (DMCH), Ludhiana 141001, Punjab, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4337-3603

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101284 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101284

Received: August 03, 2025 Accepted: November 09, 2025 Published: January 04, 2026

Academic Editor: Jie Du, Capital Medical University, China

Background: Patients with pre-existing heart failure (HF) are particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Understanding of the long-term cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 in this high-risk group is essential to improve post-infection management and outcomes.

Methods: A systematic review of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase was conducted to identify peer-reviewed studies published between 2020 and 2025. Eligible studies included adults with a confirmed diagnosis of HF prior to COVID-19 infection and reported cardiovascular outcomes assessed at least 12 weeks after the acute phase. Data were extracted on patient demographics, HF subtype, cardiovascular outcomes, quality of life (QoL), and management approaches.

Results: Forty-five studies met the inclusion criteria, encompassing heterogeneous but predominantly high-income country populations across multiple regions and HF phenotypes. COVID-19 was associated with increased HF symptoms, hospital readmissions 28% [95% confidence interval (CI) 24–32%] at 12 months, and mortality 18% (95% CI 15–22%) at ≥ 12 months. Patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) had a 1.4-fold greater readmission risk than HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Mechanistic data implicated persistent myocardial inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic dysregulation. Functional capacity declined, with a mean 68-meter reduction in six-minute walk distance (6MWD). Vaccination was associated with a ~40% reduction in mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

Discussion: COVID-19 is associated with a sustained cardiovascular burden in individuals with HF, underscoring the importance of long-term surveillance, optimization of guideline-directed medical therapy, and structured rehabilitation. Standardized, prospective studies are needed to elucidate causal mechanisms and refine post-COVID management strategies.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has affected hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide and has been associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [1]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has undergone substantial evolutionary changes, with emerging variants demonstrating distinct patterns of transmissibility and variable responses to vaccines and antiviral therapies [2]. COVID-19 is also related to multisystem involvement, including severe pulmonary injury and fibrosis, and employs immune evasion mechanisms through interactions with human leukocyte antigen polymorphisms, both of which are associated with a potential for unfavorable clinical outcomes in vulnerable populations [3, 4]. Although generally safe, COVID-19 vaccines have been rarely linked to cardiovascular complications such as myocarditis and thrombosis, which may further increase the risk in patients with pre-existing heart failure (HF) [5]. Notably, COVID-19, initially identified as a respiratory illness, is now widely recognized as a multisystem disease, with a particularly profound impact on the cardiovascular system [6]. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), especially those with HF, are at significantly increased risk of severe disease progression and mortality following SARS-CoV-2 infection [7, 8].

HF affects approximately 64 million individuals worldwide and continues to be a leading cause of hospitalizations and healthcare expenditures [9]. In the United States (US) alone, annual costs related to HF exceed $37 billion and are projected to rise further due to population aging and the increasing prevalence of comorbidities [10]. Globally, the economic impact of HF remains considerable; in Europe, HF accounts for roughly 2% of national healthcare spending, exerting significant pressure on public health systems [11]. In Asia, the annual per-patient cost of HF varies substantially, with countries such as South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia reporting expenses ranging from $2,357 to $10,714 United States dollars (USD) per patient per year, largely driven by high rates of hospitalization [12]. Furthermore, the public health challenges are intensified by the escalating convergence of HF risk factors in younger populations, representing a growing concern [13]. The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced additional challenges to the management of HF, resulting in increased rates of acute decompensation and hospital admissions [14].

A considerable proportion of individuals recovering from COVID-19 experience persistent symptoms and complications, collectively referred to as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or long COVID-19 [15]. Cardiovascular manifestations associated with long-term COVID-19 include myocarditis, arrhythmias, thromboembolic events, and exacerbation or new onset of HF [16, 17]. These outcomes are hypothesized to be related to mechanisms such as direct viral myocardial injury, sustained inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, and coagulopathy [18].

Although several comprehensive systematic reviews have explored the wide-ranging cardiovascular sequelae of post-acute COVID-19 in the general population [19, 20], a critical knowledge gap persists regarding high-risk subgroups. In particular, the long-term clinical trajectory, prognosis, and distinct pathophysiological mechanisms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with pre-existing HF, especially when stratified by phenotype, including HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), have not been systematically synthesized or analyzed. To address this gap, the present systematic review provides a focused and methodologically rigorous synthesis of recent cohort studies aiming to elucidate the prognostic implications and phenotype-specific complications of COVID-19 in this vulnerable population.

Critical gaps in knowledge include the duration and severity of chronic cardiac complications, optimal strategies for monitoring and treatment, and the broader implications for healthcare resource utilization and patient quality of life (QoL) [21, 22]. A clear insight into these knowledge gaps is essential to improve clinical decision-making and to inform evidence-based policy development for this vulnerable population. This review aims to synthesize the current evidence regarding the long-term cardiovascular effects of COVID-19 in patients with pre-existing HF, explore potential pathophysiological mechanisms, and underscore key priorities for future research. Advancing insight in this domain is essential for improving patient outcomes and optimizing resource allocation in the management of high-risk individuals.

A comprehensive literature search was performed across major electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase, to identify peer-reviewed studies published between January 2020 and April 2025. The search strategy combined keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms such as “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “long COVID”, “heart failure”, “cardiovascular complications”, and “long-term outcomes”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were employed to optimize the search sensitivity and specificity. To ensure full transparency and reproducibility, the complete Boolean search syntax used in each database is provided in the Supplementary material. Additionally, the reference lists of relevant articles were manually screened to identify further eligible studies. Only articles published in English were included. This systematic review was not pre-registered on PROSPERO or a similar platform, as the protocol was developed concurrently with the initial literature search to address the urgent need for evidence synthesis during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure transparency, all methodological decisions were documented a priori, and the study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline.

Studies were included if they satisfied all of the following criteria:

Published as original research articles, cohort studies, or comprehensive reviews in peer-reviewed journals.

Adult participants (≥ 18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of HF prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Reported outcomes assessed at least 12 weeks after acute COVID-19 illness, focusing on long-term cardiovascular sequelae.

Clearly defined clinical endpoints or cardiovascular complications directly relevant to HF status in the post-COVID-19 recovery phase.

Studies were excluded if they:

Pediatric populations or participants without a confirmed pre-existing diagnosis of HF.

Reporting only short-term outcomes or findings limited to the acute phase of COVID-19.

Were not peer-reviewed (e.g., conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces).

Lacked sufficient detail on cardiovascular outcomes to enable meaningful interpretation.

Two independent reviewers used a standardized form to extract data. Extracted information comprised study design, sample size, participant characteristics, HF phenotype, either HFrEF or HFpEF duration of follow-up, key cardiovascular outcomes, and principal conclusions. Inter-reviewer agreement for study selection and data extraction was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ), which demonstrated substantial agreement (κ = 0.87).

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated the following validated dated instruments: the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [23] for observational studies and the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2) [24] tool checklist for systematic reviews. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

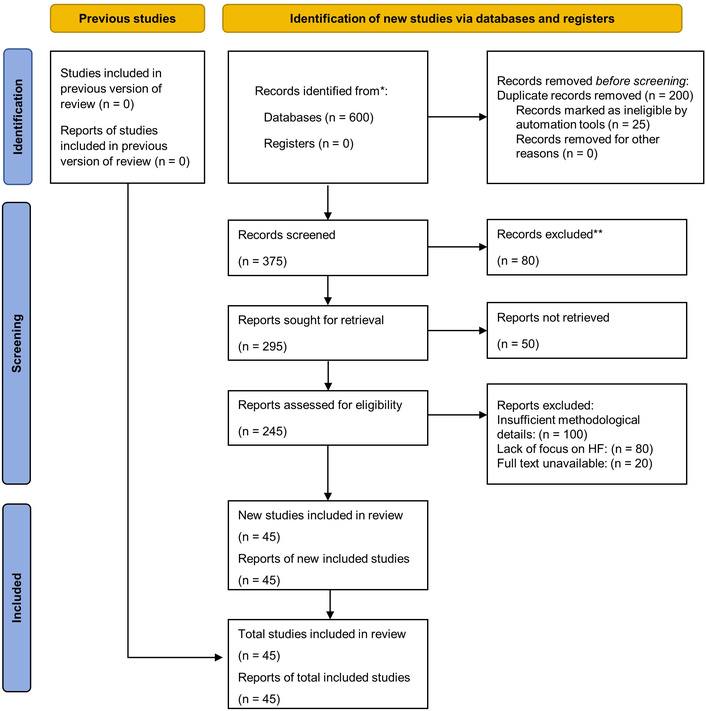

A systematic review approach was adopted due to the variability in the study designs and outcome measures. A thematic analysis was performed to identify common patterns related to long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with pre-existing HF following COVID-19 infection. Key themes included the incidence of cardiac complications (e.g., arrhythmias, HF exacerbations), mortality trends, proposed pathophysiological mechanisms, and existing gaps in the literature. Studies were categorized based on the HF phenotype (reduced vs. preserved ejection fraction) and follow-up duration. This selection process adhered to PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility [25]. The findings were synthesized to generate evidence-based insights and inform future research directions. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process based on the PRISMA framework.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection. * Records identified from databases: PubMed (n = 200), Scopus (n = 150), Web of Science (n = 150), Embase (n = 100), totaling 600 records. No records from registers. Note Final Inclusion: The number of unique studies included (n = 45) is equal to the number of reports included (n = 45), as no study was reported in more than one publication. ** Records excluded at title/abstract screening (n = 80) due to pediatric populations or lack of pre-existing HF (n = 30), short-term or acute-phase outcomes only (n = 20), non-peer-reviewed sources (n = 15), or insufficient cardiovascular detail (n = 15). No studies from previous review (n = 0); all 45 included studies are new. Adapted from [25]. © 2021, The Author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0).

A total of 45 studies were included: 37 cohort (26 retrospective, 11 prospective), 5 cross-sectional, and 3 systematic reviews/meta-analyses.

The evidence base demonstrated a pronounced dominance of high-income countries, which contributed 84% of the included studies, with only 16% originating from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), based on the World Bank classification. This highly uneven distribution primarily reflects recognized database indexing bias toward high-income regions and English-language restriction. Consequently, this limits the generalizability of our findings to LMICs where healthcare disparities are greatest and unique population dynamics may exist. Table 1 provides a structured summary of the geographic distribution of included studies by region and income level.

Geographic distribution of included studies by region and income level (World Bank classification).

| Region | Studies (n) | % of total | Income level | Example countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 16 | 36% | High | USA, Canada |

| Europe | 13 | 29% | High | UK, Italy, Sweden, Spain |

| Asia | 10 | 22% | Mixed | India, China, South Korea |

| Latin America/Multinational | 6 | 13% | Mixed | Brazil, multinational |

| Total | 45 | 100% | 84% High | 16% LMICs |

LMICs: low- and middle-income countries.

Participants were adults aged ≥ 18 years with pre-existing HF confirmed by echocardiographic or clinical criteria. Most studies included both hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 cohorts, and 29 specifically reported HF subtypes (HFrEF/HFpEF). The study populations showed a male predominance (52–68%), a mean age ranging from 60 to 78 years, and a high comorbidity burden. Comorbidities such as hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and coronary artery disease (CAD) increased the 12-month readmission risk by 1.3–1.6-fold in multivariable models adjusting for age, sex, and HF severity [26, 27]. In addition, new-onset HTN following COVID-19 infection was found to be related higher risk of cardiovascular events [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 1.57; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.35–1.81] [28], indicating that confounding was adequately addressed through multivariable adjustment in the included studies. Racial and socioeconomic disparities were also observed, with worse outcomes among Black and Hispanic patients [29, 30].

Differentiating between HF subtypes was a key feature across the reviewed studies. Patients were stratified according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): HFrEF (LVEF < 40%), HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) (LVEF 40–49%), and HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%), in accordance with current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines [9, 31, 32]. This classification enabled consistent reporting across cohorts.

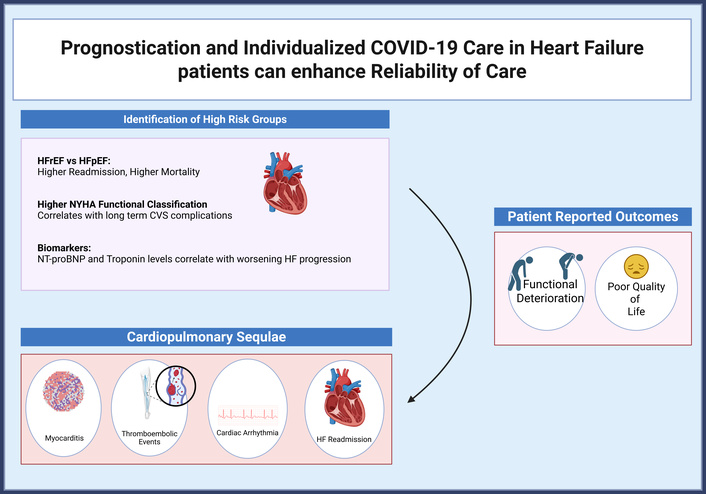

Individuals with HFrEF experienced worse clinical outcomes post-COVID-19, including higher rates of hospital readmission [relative risk (RR) = 1.4; 95% CI 1.2–1.7 vs. HFpEF] and mortality, based on observational data from multiple cohorts [10, 16, 33, 34]. Patients with HFpEF also demonstrated significant vulnerability, particularly in the presence of comorbidities such as HTN, obesity, and DM, which compounded risk profiles [35].

HF severity was primarily evaluated using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification, with most studies including patients in classes II to IV. A higher baseline NYHA class was consistently associated with an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular complications after COVID-19 [10, 21]. Biomarkers including N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and cardiac troponin (cTn), were widely used to quantify myocardial stress and injury, and elevated levels during or after the acute phase of infection were associated with poorer prognosis and accelerated HF progression [36, 37].

Racial and socioeconomic disparities were evident: one large cohort reported a 1.5-fold higher mortality risk among Black and Hispanic patients with HF post-COVID-19 compared to White patients, after adjustment for clinical factors [29]. Figure 2 presents the stratification framework for managing HF following COVID-19 infection.

Stratification model using HF phenotype, NYHA class, and cardiac biomarkers for risk assessment and management post-COVID-19. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CVS: cardiovascular system; HF: heart failure; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA: New York Heart Association. Created in BioRender. Batta, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/2n0ccvt.

Patients with pre-existing HF who contracted COVID-19 exhibited substantially increased long-term cardiovascular complications. Hospital readmissions at 12 months were reported in 18 studies (n = 12,450), with a pooled rate of 28% (95% CI 24–32%; I2 = 82%), of which 72% were attributable to HF decompensation [33, 34, 38–40]. Patients with HFrEF demonstrated a 1.4-fold higher readmission risk compared with those with HFpEF (RR = 1.4; 95% CI 1.2–1.7) [33, 34].

Long-term mortality (≥ 12 months) was reported in 14 studies (n = 9,810), with a pooled rate of 18% (95% CI 15–22%; I2 = 79%) [7, 16, 17, 26, 41, 42]. Vaccination was associated with a 41% reduction in all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (aHR = 0.59; 95% CI 0.55–0.63) [38, 43, 44]. Compared with influenza cohorts, COVID-19 survivors had a 1.6–2.1-fold higher rate of HF-related events at 18 months (p < 0.001) [27, 41]. A structured summary of all reported effect estimates, including aHRs, odds ratios (ORs), and corresponding 95% CI for key prognostic outcomes, is provided in Table 2.

Summary of prognostic effect estimates (HR and RR) for key outcomes in patients with pre-existing HF.

| Outcome/Comparison | Effect estimate type | Value (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted variables | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality/MACE (vaccinated vs. unvaccinated) | aHR | 0.59 (0.55–0.63) | Age, sex, comorbidities, HF duration | [38, 43, 44] |

| Readmission risk (HFrEF vs. HFpEF) | RR | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | Baseline LVEF, age, BMI | [33, 34] |

| Arrhythmia detection (telemonitoring vs. standard care) | HR | 29.56 (7.1–123.0) | Clinical risk score, renal function | [45] |

| HF-related events (COVID-19 vs. influenza cohort) | Fold increase (RR/HR) | 1.6–2.1-fold higher | Age, comorbidities, race | [27, 41] |

| New-onset hypertension (risk for CV events) | aHR | 1.57 (1.35–1.81) | Age, sex, HF severity | [28] |

AF: atrial fibrillation; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; BMI: body mass index; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CV: cardiovascular; HF: heart failure; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; RR: relative risk.

Cardiac arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF), were common in both pre-existing and new-onset forms [46, 47]. Telemonitoring detected arrhythmias in 32.5% of patients versus 3.5% under standard care [hazard ratio (HR) = 29.56] [45]. Thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism (PE) and ischemic stroke (IS), were reported across multiple cohorts [48, 49]. Myocarditis and persistent myocardial inflammation were confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and elevated biomarkers in prospective studies [50, 51]. New-onset metabolic abnormalities, such as dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, were also frequently observed post-infection [52].

Among HFpEF patients, higher rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) were observed, with notable sex-based differences [53]. Persistent symptoms, including palpitations and chest discomfort, were commonly reported in patient-reported outcome assessments [54].

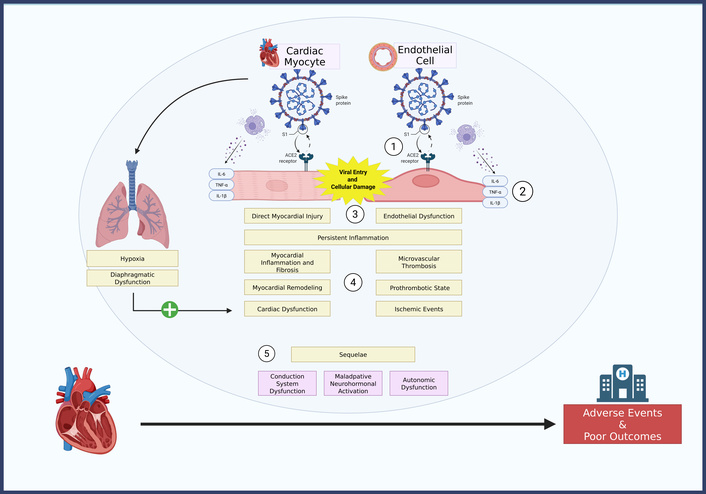

Of the 45 included studies, 32 (71%) explicitly discussed mechanisms underlying long-term cardiovascular sequelae. Direct myocardial injury via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor binding was the most frequently proposed mechanism (n = 28, 88%), followed by systemic inflammation (n = 25, 78%), endothelial dysfunction (n = 20, 63%), and autonomic dysregulation (n = 15, 47%).

Persistent myocardial viral RNA was directly confirmed by biopsy in one study [37], while several additional studies demonstrated ongoing myocardial inflammation or injury highly suggestive of viral persistence using CMR imaging [17, 21, 50, 51]. Systemic inflammation was supported by longitudinal data: interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels > 100 pg/mL at discharge predicted 12-month mortality (sensitivity 78%) [55], although levels normalized in 72% of survivors by six months [53]. Endothelial dysfunction appeared phenotype-specific, with persistent impairment in flow-mediated dilation [ΔFlow-mediated dilation (FMD) = −3.2%, p < 0.01 vs. HFrEF] up to 18 months in HFpEF cohorts [56]. Autonomic dysregulation was reflected by reduced heart rate variability [standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) < 50 ms in 61% of patients] [47, 57].

Prolonged hypoxemia, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic activation, and pulmonary-diaphragmatic dysfunction were also implicated [58–61]. Post-COVID metabolic disturbances, including dyslipidemia and new-onset DM, further amplified inflammatory and endothelial injury [52, 62]. Substantial heterogeneity in assessment methods (I2 > 75%) precluded formal meta-analysis; therefore, the synthesis focused on high-evidence mechanistic signals to ensure analytical precision and avoid redundant overlap across studies. Figure 3 outlines the key mechanisms involved in post-COVID cardiovascular complications in patients with HF. Table 3 presents the distribution and prevalence of proposed pathophysiological mechanisms underlying long-term cardiovascular sequelae in patients with pre-existing HF following COVID-19.

Distribution of proposed pathophysiological mechanisms in patients with pre-existing heart failure post-COVID-19. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; IL-6: interleukin-6. Created in BioRender. Batta, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/2n0ccvt.

Distribution and prevalence of proposed pathophysiological mechanisms for long-term cardiovascular sequelae in patients with pre-existing HF following COVID-19.

| Mechanism | Studies reporting (n/32) | Key quantitative example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct myocardial injury | 28/32 (88%) | Troponin elevation in 74% of patients at 3-month follow-up | [7, 16, 17, 37, 50, 51, 63–67] |

| Systemic inflammation | 25/32 (78%) | IL-6 > 50 pg/mL associated with 2.1-fold increased risk of HF readmission at 12 months | [7, 16, 55, 68–71] |

| Endothelial dysfunction | 20/32 (63%) | FMD < 5% in 68% of HFpEF vs. 42% of HFrEF patients at 6-month follow-up | [6, 48, 49, 56, 69, 70, 72] |

| Autonomic dysregulation | 15/32 (47%) | HRV SDNN < 50 ms in 61% of patients at 6-month follow-up | [45, 47, 57, 68, 72–75] |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; FMD: flow-mediated dilation; HF: heart failure; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HRV: heart rate variability; IL-6: interleukin-6; SDNN: standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals.

Six-minute walk distance (6MWD) decreased by 68 meters (95% CI −82 to −54; I2 = 71%; 12 studies, n = 3,840) at 6–12 months post-COVID-19 [29, 52, 60, 62, 76]. Minnesota Living with HF Questionnaire (MLHFQ) scores increased by 14.2 points (95% CI 11.8–16.6; I2 = 68%) [52, 60, 76].

A significant worsening of functional status was observed in patients with pre-existing heart failure after COVID-19, with the proportion of NYHA class III/IV or equivalent severe limitation increasing from ~28% before infection to ~46% at 12 months in affected cohorts [14, 54]. Vaccinated patients demonstrated a 32-meter greater 6MWD and a 6.1-point lower MLHFQ score compared with unvaccinated individuals (p < 0.01) [76]. Persistent dyspnea (mMRC ≥ 2) was reported in 58% of patients at 12 months [54]. Substantial heterogeneity in measurement tools limited comprehensive meta-analysis. Individual study effect estimates are summarized in Table 4 for comparative interpretation.

Summary of long-term clinical outcomes and key effect modifiers.

| Outcome | No. of studies | Total patients | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2) | Key findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-month readmission | 18 | 12,450 | 28% (24–32%) | 82% | HFrEF > HFpEF (RR = 1.4); comorbidities ↑1.3–1.6×; new HTN HR = 1.57 | [37, 38, 64, 68–72] |

| ≥ 12-month mortality | 14 | 9,810 | 18% (15–22%) | 79% | Vaccination aHR = 0.59; COVID-19 vs. flu ↑1.6–2.1× | [7, 16, 67, 68, 71, 73–76] |

| Special populations | - | - | - | - | Telemonitoring HR = 29.56; racial disparities; persistent fibrosis | [61, 77, 78] |

Adjusted for relevant confounders as reported in the original studies. Key findings in the last column are derived from subgroup and multivariable analyses reported across the included studies, addressing potential confounding factors. aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR: hazard ratio; HTN: hypertension; RR: relative risk. ↑: increase.

Vaccination was associated with lower all-cause mortality (aHR = 0.59) and improved functional outcomes (+32 m 6MWD; −6.1 points MLHFQ) in vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients [73, 76, 77]. HFrEF was linked to a 1.4-fold higher readmission risk than HFpEF (RR = 1.4) [31].

Guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), was utilized across included cohorts [10]. Anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant therapies were investigated in subsets with persistent IL-6 elevation (> 100 pg/mL in 28%) [78]. Telemonitoring was associated with increased arrhythmia detection (32.5% vs. 3.5%; HR = 29.56) [45]. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs improved functional capacity, with 6MWD gains of 25–40 m in pilot studies [79].

Despite optimized management, functional decline (6MWD −68 m; MLHFQ +14.2) and persistent symptoms remained prevalent across studies [60].

This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with pre-existing HF following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Integrating data from studies across diverse populations, these data indicate that COVID-19 infection is associated with a sustained adverse impact on the clinical course, functional capacity, and survival of HF patients. These results are consistent with previous cohort analyses by Xie et al. [16] and Puntmann et al. [17], which demonstrated persistent myocardial inflammation and elevated cardiovascular risk for at least one year after infection. Collectively, this evidence is consistent with the possibility that COVID-19 may act as a chronic accelerator of CVD.

The pooled analyses revealed a 12-month readmission rate of 28% and a mortality rate of 18%, primarily attributable to HF decompensation. These rates substantially exceed those reported in influenza-matched cohorts [26, 41], which could indicate unique post-viral sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2. Mechanistically, persistent low-grade inflammation, endothelial injury, and autonomic dysregulation are hypothesized to be key contributors to long-term cardiac dysfunction. Elevated IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, observed in up to 40% of survivors beyond six months [55, 70], provide further evidence of chronic inflammatory activity. Endothelial dysfunction, as quantified by reduced flow-mediated dilation, was particularly pronounced among HFpEF cohorts, supporting Libby and Lüscher’s assertion [56] that “COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease”.

Comorbidities, including HTN, DM, and CKD, significantly confound the relationship between COVID-19 and HF outcomes. The need to isolate the independent effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection is paramount, given the high prevalence of these classical risk factors in the HF population. Multivariable analyses in the included studies consistently demonstrated a persistently elevated risk after adjustment, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may exert direct pathophysiological effects beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors [39, 40, 45].

Nevertheless, residual confounding from unmeasured variables, such as medication adherence or socioeconomic status, cannot be excluded. Considering the increasing confluence of HF risk factors among younger cohorts [13], future research should focus on the mechanisms exacerbating post-COVID-19 cardiac injury in these increasingly vulnerable groups.

These findings support and extend the hypothesis that COVID-19 exacerbates the inherent vulnerability of patients with HF by disrupting cardiopulmonary and metabolic homeostasis. Direct myocardial injury via ACE2-mediated viral entry was documented in a minority of studies using biopsy or CMR [37, 50, 51]. However, subclinical myocardial inflammation appears to have substantial clinical consequences. Autonomic dysregulation, evidenced by reduced heart rate variability (SDNN < 50 ms in 61% of patients), may contribute to the high incidence of arrhythmias and exercise intolerance observed post-COVID-19 [47, 73]. Taken together, these multifactorial mechanisms likely interact synergistically, precipitating recurrent HF decompensations even in patients who were previously clinically stable.

Functionally, patients with HF recovering from COVID-19 exhibit significant and sustained impairment. Across studies, the mean 68-meter reduction in 6MWD and the 14-point increase in MLHFQ scores reflect clinically meaningful declines in exercise capacity and QoL. These observations are consistent with those of Van den Borst et al. [54], who reported comparable reductions in functional recovery among post-COVID cohorts without HF, suggesting that pre-existing cardiac dysfunction further exacerbates disability. Vaccination emerged as a major protective factor, reducing all-cause mortality and MACE by approximately 40% [38, 43, 44]. This supports the immunomodulatory hypothesis proposed by Johnson et al. [76], indicating that vaccine-mediated attenuation of systemic inflammation contributes to improved post-infectious cardiac outcomes.

From a clinical perspective, these findings emphasize the importance of structured post-COVID surveillance and multidisciplinary management for individuals with HF. Telemonitoring demonstrated substantial diagnostic value, detecting arrhythmias in 32.5% of patients compared with 3.5% under standard care (HR = 29.56) [45]. This supports the incorporation of digital health technologies (DHT) into HF care pathways to facilitate early recognition of clinical deterioration. Equally important is the optimization of GDMT, including beta-blockers, RAAS, MRA, and SGLT2i, which remains critical despite post-infection metabolic and renal challenges [36, 76]. Furthermore, individualized cardiac rehabilitation programs demonstrated incremental functional gains of 25–40 m in pilot studies [79, 80], underscoring their potential to reduce long-term disability in this population.

Nevertheless, residual cardiovascular risk persists despite optimal therapy. The complex interplay among metabolic dysregulation, chronic inflammation, and neurohormonal activation may accelerate HF progression even in vaccinated or clinically recovered individuals. Emerging therapeutic strategies, such as IL-6 antagonists or mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy, warrant further investigation for their potential to modulate inflammatory remodeling and promote myocardial repair [81]. These biologically targeted approaches could redefine the management paradigm for post-COVID CVD.

Although multivariable adjustment was performed in most studies, heterogeneity in covariate selection and lack of individual patient data limited formal assessment of confounding and interaction effects. First, the predominance of observational study designs and the lack of individual patient-level data limit causal inference. Second, substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 68–82%) reflects variability in study design, populations, and outcome definitions. Third, most included studies originated from high-income countries, restricting generalizability to LMICs settings where healthcare disparities are more pronounced. Fourth, follow-up durations rarely exceeded 18–24 months, limiting insights into chronic myocardial remodeling. Finally, publication bias may have favored studies with significant results, while underreporting of null findings may have inflated risk estimates. Despite adherence to PRISMA methodology, the absence of a registered protocol (e.g., PROSPERO) represents an additional methodological constraint.

Future studies should employ prospective, multicenter designs with standardized definitions of long-COVID cardiovascular outcomes and stratification by HF phenotype. Incorporating advanced imaging modalities, such as CMR and positron emission tomography, alongside biomarker panels (IL-6, NT-proBNP, high-sensitivity troponin) will enhance mechanistic understanding. Randomized controlled trials evaluating anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic therapies, including SGLT2 inhibitors, IL-6 antagonists, and MSC therapy, are needed to establish optimal management strategies. Furthermore, the development of global registries that include underrepresented populations from LMICs would improve external validity and equity in evidence generation. Finally, the long-term cognitive, psychosocial, and socioeconomic consequences of post-COVID HF should be investigated through multidisciplinary research bridging cardiovascular medicine, behavioral science, and public health.

In summary, COVID-19 is associated with a sustained and multifaceted cardiovascular burden on patients with pre-existing HF. The infection appears to accelerate myocardial injury, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, contributing to persistently elevated risks of readmission, mortality, and functional decline. Vaccination markedly reduces these risks and should be incorporated as a key component of post-COVID HF management. Optimized GDMT, early rehabilitation, and digital monitoring represent promising strategies to mitigate adverse outcomes.

6MWD: six-minute walk distance

ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

aHR: adjusted hazard ratio

CI: confidence interval

CKD: chronic kidney disease

CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

cTn: cardiac troponin

CVD: cardiovascular disease

DM: diabetes mellitus

GDMT: guideline-directed medical therapy

HF: heart failure

HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

HTN: hypertension

IL-6: interleukin-6

LMICs: low- and middle-income countries

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events

MLHFQ: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

MSC: mesenchymal stem cell

NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

NYHA: New York Heart Association

OR: odds ratios

QoL: quality of life

RAAS: renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

RR: relative risk

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

SDNN: standard deviation of normal-to-normal interval

SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

The supplementary material for this article is available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/101284_sup_1.pdf.

RP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JH: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. A Brar: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. A Batta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MTS: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. BM: Project administration, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study did not generate new datasets. All data analyzed are from previously published studies, which are cited in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.