Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya

2Department of Medicine, Neurology Unit, Benghazi Medical Center, Benghazi, Libya

Email: Anwaar.benour@UOB.edu.ly

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya

3Department of Medicine, Gastroenterology Unit, Benghazi Medical Center, Benghazi, Libya

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3295-5138

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya

2Department of Medicine, Neurology Unit, Benghazi Medical Center, Benghazi, Libya

Explor Neurosci. 2025;4:1006120 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2025.1006120

Received: October 30, 2025 Accepted: December 18, 2025 Published: December 23, 2025

Academic Editor: Jinwei Zhang, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

The article belongs to the special issue Advances in Epilepsy Research

Neurogenetic disorders remain genetically uncharacterized in many populations, including Libya. We report three Libyan patients from two consanguineous families with pathogenic variants in sodium channel genes. Two adult sisters (Patients 1 & 2) presented with global developmental delay and progressive spastic paraparesis without epilepsy. Whole exome sequencing identified the same heterozygous SCN8A variant (c.142G>A; p.Asp48Asn) in both sisters, classified as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). Its occurrence in two affected siblings with a consistent phenotype and the absence of other explanatory variants provide supporting evidence for its potential pathogenicity. These cases represent the first documented instances of a suspected SCN8A-related disorder in Libya. A third, unrelated 10-year-old boy (Patient 3) with a phenotype consistent with Dravet syndrome, including refractory seizures and neurodevelopmental regression, was found to harbor a likely pathogenic heterozygous SCN1A variant (c.2113del; p.Glu705Lysfs*10). This report expands the genetic and phenotypic spectrum of neurological disorders in Libya and underscores the critical role of genetic testing, while also highlighting the need for segregation studies to achieve a definitive molecular diagnosis.

Neurogenetic disorders, caused by pathogenic variants in genes critical for neuronal function, can manifest with a wide range of symptoms, including epilepsy, neurodevelopmental delays, and movement disorders [1, 2]. Pathogenic variants in the SCN8A gene, which encodes the voltage-gated sodium channel subunit Nav1.6, are typically associated with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEE) [3–5]. However, the phenotypic spectrum has broadened to include neurodevelopmental disorders with prominent motor deficits (such as spastic paraparesis and extrapyramidal features) in the absence of epilepsy [6–9]. These non-epileptic phenotypes are often linked to specific gain-of-function missense mutations that alter channel kinetics [10]. In contrast, variants in SCN1A, which encodes the Nav1.1 channel, are a common cause of Dravet syndrome, a severe infant-onset DEE characterized by refractory seizures and developmental regression [11]. SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome typically results from haploinsufficiency due to loss-of-function mutations, impairing inhibitory interneuron function [12].

While SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome has been previously documented in Libya [13, 14], SCN8A-related disorders have not. Here, we present the first Libyan family with two siblings harboring an SCN8A variant and a separate case of SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome. This report aims to elucidate the genetic etiology of rare neurological conditions in Libya and to contribute to a national program for documenting neurogenetic disorders and improving future diagnostic and therapeutic pathways.

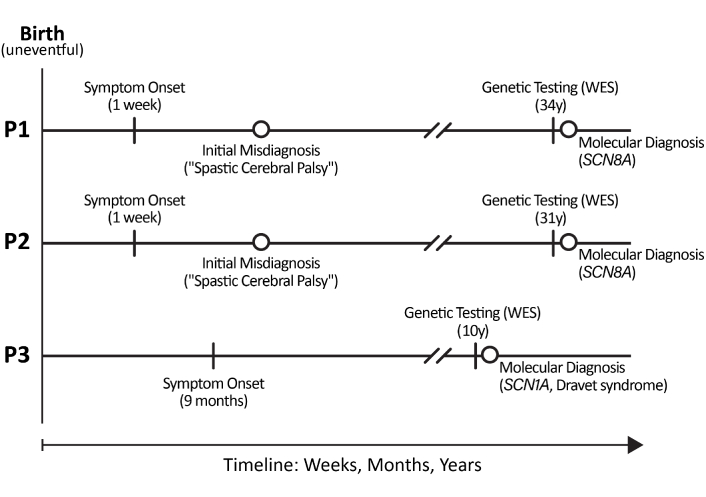

The diagnostic journey for each patient is summarized in Figure 1.

Historical and diagnostic timeline for the three patients. P1: patient 1; P2: patient 2; P3: patient 3. WES: whole exome sequencing.

Patient 1:

Birth: Uneventful.

Week 1: High-grade fever.

At 8 months: Sat independently.

At 3.5 years: Achieved independent ambulation.

Childhood-adulthood: Progressive spastic paraparesis and spinal deformity.

At 34 years: Genetic testing performed.

Patient 2:

Birth: Uneventful.

Week 1: Febrile episode.

Early childhood: Failure to achieve motor milestones.

Adulthood: Severe spastic quadriplegia with extrapyramidal features.

At 31 years: Genetic testing performed.

Patient 3:

Birth: Uneventful.

At 9 months: Seizure onset, fever.

Infancy-childhood: Refractory epilepsy with developmental regression.

At 10 years: Genetic testing performed.

Ongoing: Chronic epilepsy management.

The patients were identified through the Eastern Libyan Sub-Committee for Genetic Neuromuscular Disorders (ELSGNMD), which operates under the Libyan National Program for Neuromuscular Diseases. The ELSGNMD is one of three subcommittees established in Libya’s major health sectors (east, west, and south) and, while focused on neuromuscular diseases, has expanded to enable the diagnosis of other neurogenetic disorders.

Family 1 (patients 1 and 2): Two adult sisters from consanguineous families with no relevant past medical history. Their parents are both clinically healthy, with no personal history of neurological symptoms, including seizures, developmental delay, or movement disorders.

Family 2 (patient 3): A boy from an unrelated consanguineous family in eastern Libya with no relevant past medical history. His parents are also reported to be neurologically normal.

Patient 1: A 34-year-old female, born after an uneventful pregnancy and delivery, presented with a history of high-grade fever at one week of age. This was followed by delayed motor milestones: she sat at 8 months and walked at 3.5 years. She developed a progressive spastic paraparesis. Notably, she had no history of seizures.

Patient 2: The 31-year-old sister of patient 1 presented similarly with fever in the first week of life and profound global developmental delay. Like her sister, she had no history of seizures. She never achieved independent ambulation.

Patient 3: A 10-year-old boy presented with refractory focal and generalized tonic-clonic seizures beginning at 9 months of age, often triggered by fever. This was followed by neurodevelopmental regression and episodes of status epilepticus.

Patient 1: Neurological examination confirmed spasticity in the lower limbs with kyphoscoliosis and contractures. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated over all four limbs, with bilateral ankle clonus and extensor plantar responses. Intellectual function was normal.

Patient 2: Neurological examination revealed severe spastic quadriplegia, kyphoscoliosis, orofacial dyskinesia, and athetosis. Intellectual function was mildly impaired.

Patient 3: Has severe intellectual disability, autistic features, and generalized dystonia.

Paraclinical tests: Baseline laboratory tests and brain MRI were normal in all patients. An interictal electroencephalogram (EEG) was not performed in patients 1 and 2 due to the lack of seizures. In patient 3, the interictal EEG showed generalized spike-and-wave discharges. The assessment of developmental milestones and intellectual function was based on detailed history-taking and clinical observation. Standardized neuropsychological assessments were not available for the patients due to the long-standing nature of their condition and the retrospective nature of this study.

Genetic testing: Whole exome sequencing (WES) was pursued due to atypical and progressive course in patients 1 and 2, and to confirm a clinical diagnosis in patient 3.

Blood samples were collected from probands in EDTA tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted and sent for WES to Bioscientia International (Ingelheim, Germany). The coding exons of over 20,000 genes were enriched using Roche/KAPA capture technology and sequenced on an Illumina system (next-generation sequencing, NGS). Data analysis focused on X-linked, autosomal dominant, and recessive disorders. Variant interpretation and classification were performed according to the joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines [15]. All genomic coordinates are based on the GRCh37/hg19 human genome build.

In patients 1 and 2, WES revealed a heterozygous SCN8A variant (c.142G>A; p.Asp48Asn), classified as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). In patient 3, a heterozygous frameshift variant in SCN1A (c.2113del; p.Glu705Lysfs*10), was identified and classified as likely pathogenic, confirming the clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome.

Diagnostic challenges: Patients 1 & 2 were initially suspected to have spastic cerebral palsy. Patient 3 was clinically diagnosed with Dravet syndrome based on phenotype. Genetic testing was not performed on the parents to determine their carrier status for the identified variants.

Patients 1 & 2: Management has been supportive and symptomatic, focusing on physiotherapy for spasticity and contractures, and orthopedic care for kyphoscoliosis. No antiseizure medications were required.

Patient 3: Managed with a combination of valproate and levetiracetam for seizure control. He also receives multidisciplinary support, including physical therapy and special education.

Patients 1 & 2: Both have a stable but non-progressive neurological deficit in adulthood. No seizure activity has been reported. The molecular finding has ended their diagnostic journey and informed genetic counseling for the family, though recurrence risk remains uncertain without segregation analysis.

Patient 3: He continues to experience refractory seizures despite dual therapy. The genetic confirmation of SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome has optimized his therapeutic strategy (avoiding sodium channel blockers) and provided a definitive etiology for the family.

Families expressed that the long diagnostic journey was a source of significant anxiety. Receiving a molecular diagnosis, even of a VUS in the case of family 1, provided a sense of closure and a biological explanation for their children’s conditions. They hope this finding might assist other families with similar presentations. For family 2, they expressed their appreciation for the confirmation of Dravet syndrome, stating that it provided clarity and helped in connecting them with appropriate support networks and clinical management pathways.

Clinical and genetic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical and genetic characteristics of the patients.

| Feature | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | One week | One week | Nine months |

| Age at genetic testing | 34 years | 31 years | 10 years |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male |

| Family history | Sister affected | Sibling of patient 1 | Negative |

| Consanguinity | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Birth history | Uneventful | Uneventful | Uneventful |

| Developmental milestones | Delayed | Delayed | Delayed |

| Intellectual function | Normal | Mildly impaired | Severely impaired |

| Seizure | No | No | Yes (intractable) |

| Anti-seizure medication | No | No | Valproate and levetiracetam |

| Major neurological features | Spastic paraparesis, contractures, kyphoscoliosis | Spastic quadriplegia, athetosis, orofacial dyskinesia, kyphoscoliosis | Dystonia, autism, global delay |

| MRI head | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Laboratory tests | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| EEG | Not performed | Not performed | Generalized spike and wave |

| Gene | SCN8A (NM_014191.4) | SCN8A (NM_014191.4) | SCN1A (NM_001165963.3) |

| Associated disorder | SCN8A-related neurodevelopmental disorder | SCN8A-related neurodevelopmental disorder | Dravet syndrome |

| Variant* | c.142G>Ap.Asp48AsnChr12:52056743 | c.142G>Ap.Asp48AsnChr12:52056743 | c.2113delp.Glu705Lysfs*10Chr2:166898864 |

| Zygosity | Heterozygous | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| ACMG classification | VUS | VUS | Likely pathogenic |

ACMG: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; VUS: variant of uncertain significance; EEG: electroencephalogram. * All genomic coordinates are based on the GRCh37/hg19 human genome build.

This report describes the first Libyan patients with SCN8A-related neurodevelopmental disorder and a confirmed case of SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome. The two sisters with the SCN8A p.Asp48Asn variant exhibited a similar non-epileptic phenotype characterized by global developmental delay and progressive spastic paraparesis with extrapyramidal features, though with significant intrafamilial variability in severity. This aligns with the expanding spectrum of SCN8A-related disorders, which includes patients with predominant pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs without epilepsy [16, 17]. The international SCN8A patient registry notes that approximately 12% of affected individuals have not experienced seizures [18]. On the other hand, the non-epileptic phenotype of SCN8A-related disorders has not been reported in Arab countries, probably due to a lack of information about rare diseases.

In our patients, the SCN8A variant (c.142G>A; p.Asp48Asn) was classified as a VUS. However, a systematic evaluation using ACMG/AMP guidelines reveals compelling evidence for its potential role in the disease [15]. The variant’s absence from large population databases (evidence code PM2) indicates it is a rare change not found in the healthy population. Furthermore, multiple computational prediction tools consistently suggest that the p.Asp48Asn change has a deleterious effect on the protein (evidence code PP3). The most significant evidence comes from its occurrence within the family, as an identical variant was identified in two affected sisters who share a highly specific and consistent neurodevelopmental phenotype (evidence code PP1_Strong). The comprehensive nature of WES and the absence of other plausible explanatory variants further strengthen the association. Despite this accumulation of evidence (PM2, PP3, PP1_Strong), we maintain scientific caution. A definitive reclassification is precluded because we lack segregation analysis to confirm the variant’s de novo status, which would provide critical evidence (PS2), or to rule out inherited mosaicism. Therefore, while the data strongly suggest pathogenicity, segregation analysis remains essential for a conclusive diagnosis.

The p.Asp48 residue is located in the N-terminal domain of the Nav1.6 channel, a region involved in channel regulation and protein-protein interactions. While functional studies are needed, mutations in this domain have been linked to altered channel function, leading to neurodevelopmental disorders [17]. The motor-predominant, non-epileptic phenotype in our patients may reflect a specific gain-of-function mechanism that disrupts neuronal excitability in motor pathways without triggering overt seizures, a hypothesis consistent with other reported SCN8A cases [5, 7].

In contrast, patient 3 with the SCN1A frameshift variant (c.2113del) presented a classic Dravet syndrome phenotype. This loss-of-function mutation is expected to cause haploinsufficiency. In mouse models, SCN1A loss primarily affects GABAergic interneurons, leading to disinhibition of neuronal circuits, hyperexcitability, and the severe epilepsy and cognitive deficits characteristic of Dravet syndrome [19]. This pathophysiological understanding underscores why sodium channel blockers are often avoided in Dravet syndrome, while they may be beneficial in some gain-of-function SCN8A-related disorders.

The high rate of consanguinity in Libya, reported to be over 36% in some areas [20], is a significant public health challenge. Furthermore, the context of consanguinity in both families introduces a unique challenge for variant interpretation. While this primarily increases the risk for recessive disorders, our cases illustrate that it can also complicate the diagnosis of de novo dominant conditions, as clinicians may have a lower index of suspicion for them in consanguineous families.

This study has several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The most significant limitation is the lack of segregation analysis for the identified variants. For the SCN8A variant in patients 1 and 2, we were unable to determine its inheritance pattern. Confirming its de novo status would provide key evidence (ACMG code PS2) to upgrade its classification from VUS to likely pathogenic. Without this, we cannot definitively rule out other possibilities, such as inheritance from a parent with somatic mosaicism, which would have implications for recurrence risk counseling. Similarly, parental testing was not available for the SCN1A variant in patient 3 to confirm that it occurred de novo.

Second, the absence of functional studies for the SCN8A p.Asp48Asn variant means we can only infer its potential pathogenicity based on clinical and bioinformatic evidence. Electrophysiological assays will be required to characterize the functional impact of this variant on Nav1.6 channel properties and to confirm whether it results in a gain-of-function, as hypothesized.

Finally, while the detailed clinical characterization is a strength, the small cohort size of this case report, while reflective of the challenge in identifying rare disorders in underrepresented populations, limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies aggregating data from national or regional registries will be essential to define the full spectrum of neurogenetic disorders in Libya.

This report expands the genetic landscape of neurogenetic disorders in the Libyan population. We present the first cases of a suspected SCN8A-related neurodevelopmental disorder, characterized by a non-epileptic, motor-predominant phenotype, and a confirmed case of SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome. Our findings underscore two critical points for clinical practice in regions with high consanguinity: first, the phenotypic spectrum of known genes like SCN8A is broad and can present without classic features such as epilepsy. Second, de novo dominant disorders can and do occur within consanguineous families, necessitating a comprehensive diagnostic approach. This report highlights the indispensable role of WES in ending the diagnostic process for complex neurological presentations. The report also emphasizes that while genetic testing is a powerful tool, its full potential is realized only when coupled with clinical correlation and, where possible, segregation studies to achieve a definitive molecular diagnosis. These efforts are fundamental for improving patient management, providing accurate genetic counseling, and informing the development of national healthcare strategies for rare diseases.

AMP: Association for Molecular Pathology

ACMG: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

DEE: developmental and epileptic encephalopathies

EEG: electroencephalogram

VUS: variant of uncertain significance

WES: whole exome sequencing

The authors are deeply grateful to the patients and their families for their consent and participation in this study. We acknowledge the clinical and administrative staff of the ELSGNMD at Benghazi Medical Center for their support. We also thank the laboratory team at Bioscientia International for their genetic analysis services. During the preparation of this work, the authors used DeepSeek to improve the language and readability of the manuscript. After using DeepSeek, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed, and they take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

AMB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AMR: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. HAEZ: Validation, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Benghazi Medical Center (Approval Number: NBC: 005. H. 25.14) and was conducted in compliance with the 2024 principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the patients and their guardians.

Not applicable.

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 565

Download: 16

Times Cited: 0

Hoong Wei Gan ... William P. Whitehouse

Jerónimo Auzmendi, Alberto Lazarowski

Toshimitsu Suzuki ... Kazuhiro Yamakawa

Rodolfo Cesar Callejas-Rojas ... Ildefonso Rodriguez-Leyva