Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

†These authors share the first authorship.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6366-1039

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

†These authors share the first authorship.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9163-2350

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-6686-3104

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5918-4370

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1488-5041

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

Email: francesco.inchingolo@uniba.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3797-5883

Affiliation:

2Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Science, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy

3Unit of Maxillo-Facial Surgery and Dentistry, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, 20122 Milan, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7062-5143

Affiliation:

2Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Science, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy

3Unit of Maxillo-Facial Surgery and Dentistry, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, 20122 Milan, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7144-0984

Affiliation:

4Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Salento, 73100 Lecce, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3288-490X

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6916-0075

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

#These authors share the last authorship.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0104-6337

Affiliation:

1Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70121 Bari, Italy

#These authors share the last authorship.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5947-8987

Explor Med. 2026;7:1001381 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2026.1001381

Received: June 17, 2025 Accepted: October 04, 2025 Published: February 03, 2026

Academic Editor: Gabriele Cervino, Messina University, Italy

Background: Irreversible pulpitis is commonly associated with reduced success of inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) during root canal treatment, often leading to inadequate intraoperative pain control. Inflammatory mediators can decrease local anesthetic effectiveness and alter nerve response. Preoperative administration of anti-inflammatory drugs has been proposed as a strategy to improve anesthetic success. This review evaluates whether preoperative anti-inflammatory medication enhances the efficacy of IANB in patients with irreversible pulpitis.

Methods: Thirteen articles published between 2014 and 2024 were included in the qualitative analysis following a screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts. The quality of the studies was assessed using the ROBINS tool.

Results: Premedication with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids significantly improves the success of IANB in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. Success rates in treated groups generally range between 55% and 73%, compared to less than 40% in control groups. Ibuprofen, ketorolac, and dexamethasone were among the most effective agents.

Discussion: Premedication with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids, especially ibuprofen and dexamethasone, improves the efficacy of IANB in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, enhancing anesthetic success and reducing intraoperative pain.

Irreversible pulpitis (IP) is one of the most common dental emergencies, characterized by acute inflammation of the dental pulp, often leading to intense and persistent pain that is resistant to conventional analgesic therapy [1–3]. The recommended treatment is root canal therapy of the affected tooth; however, managing the associated pain remains one of the major challenges for dental professionals [4–6].

Inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) anesthesia is the technique of choice for pain control during dental procedures involving mandibular molars and premolars in cases of IP [7–9]. Despite the effectiveness of this technique, anesthesia failure can occur in a significant number of cases, particularly in the presence of infection or acute inflammation [7].

In recent years, the use of systemic anti-inflammatory therapies (SAIT), such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids, has been proposed as a potential strategy to enhance the effectiveness of nerve block anesthesia [10, 11]. These drugs, by reducing systemic inflammation and pain, may improve the response to local anesthesia, thus enhancing pain control in patients with IP [12, 13].

This review stands out for its broad and structured pharmacological analysis, examining not only NSAIDs—widely discussed in the literature—but also corticosteroids such as dexamethasone, which remain underexplored in this context. The inclusion of different classes of drugs allows for a more comprehensive comparison of the available preoperative anti-inflammatory strategies. The study incorporates the most up-to-date evidence, up to 2025, and employs the ROBINS tool (ROB 1.0) to rigorously assess the risk of bias in non-randomized studies, ensuring a high methodological standard.

However, despite growing interest in this therapeutic combination, scientific evidence on the effectiveness of anti-inflammatory therapy (AIT) in improving nerve block success in patients with IP remains limited and conflicting. Some studies reported significant benefits, while others found no substantial improvements [14, 15].

Therefore, the aim of this review was to systematically evaluate the effect of preoperative AIT on the success rate of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP [16, 17].

Acute inflammation of the dental pulp (Figure 1) is a biological response to harmful stimuli such as caries, trauma, bacterial infections, or chemical exposure. It involves the neural and vascular tissue within the pulp [18]. The dental pulp, made up of nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue, is enclosed in the pulp chamber within the tooth. When the pulp is damaged, an inflammatory process occurs, aiming to limit injury and restore homeostasis; if untreated, this can lead to permanent tissue damage and more serious complications [19].

During acute inflammation, chemical mediators such as prostaglandins, cytokines, and chemokines are released by the damaged tissues. These mediators cause various local effects, including vasodilation, increased capillary permeability, and hemoconcentration, resulting in swelling and heightened nerve sensitivity [20]. Pain is one of the main symptoms of acute pulp inflammation. It is often described as intense, throbbing, and continuous, and may persist even after the removal of the stimulus due to internal pressure within the tooth that cannot be released because of the rigidity of the dental walls [21].

The increased nerve sensitization makes patients particularly reactive to stimuli such as heat, cold, or pressure—and sometimes even spontaneous pain—which is often unresponsive to common painkillers. At this stage, the only effective treatment is endodontic therapy (root canal treatment) or tooth extraction [22, 23].

Inferior alveolar nerve anesthesia is one of the most common and effective techniques for pain control during dental procedures involving lower teeth, especially in surgical or endodontic treatments [24–26]. The inferior alveolar nerve (Figure 2) provides sensory innervation to most mandibular teeth, the gingiva, and the surrounding bone. It can be anesthetized through a nerve block technique, in which a local anesthetic is injected near the nerve trunk close to the mandibular foramen.

Despite its high success rate, nerve block anesthesia can present challenges, and the techniques may vary depending on individual anatomical and clinical factors [27, 28].

The traditional IANB is the most widely used technique in dentistry. It involves injecting the anesthetic into the retromolar area near the mandibular foramen, which is the entry point of the inferior alveolar nerve into the mandible [24]. The injection is administered where the nerve is most accessible along the mandibular bone; however, its clinical efficacy can vary significantly depending on the anesthetic protocol and the inflammatory state of the pulp [1].

The advantages of this technique include its ease of execution and its effectiveness in anesthetizing the entire mandibular side, including teeth, gingiva, tongue, and floor of the mouth. However, its effect may be reduced in the presence of local infections or inflammation that alter drug responsiveness, or in cases of anatomical variations such as unusual foramen positions or fibrous tissue presence [1]. The block may also be incomplete in certain areas of the mandible, such as premolars or the incisor region.

Although the traditional technique is most commonly used, variants such as the Gow-Gates and Akinosi techniques offer valid alternatives, especially in cases of failed conventional anesthesia or anatomical difficulties [22].

The Gow-Gates technique aims to block not only the inferior alveolar nerve but also other nerves involved in mandibular treatment, such as the lingual and buccal nerves. In this method, the injection is made higher than in the traditional technique, at the neck of the mandibular condyle in the pterygomandibular region [22].

An alternative to nerve block anesthesia is the intraligamentary or intrapulpal injection technique, used in cases where the initial block fails. In these methods, the anesthetic is injected directly into the pulp chamber or periodontal space to achieve a rapid, localized block [29].

The use of anti-inflammatory drugs as premedication in cases of IP primarily aims to reduce acute inflammation of the dental pulp and improve pain control during dental procedures.

NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and diclofenac are widely used for their anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic effects. These drugs work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2), which are involved in the production of prostaglandins—chemical mediators that play a crucial role in the inflammatory process and in pain sensitization [30, 31].

By reducing prostaglandin production, NSAIDs not only alleviate the pain associated with pulpitis but also help limit vasodilation and tissue edema, thereby improving perfusion and the access of anesthetic drugs to the target site [32]. This anti-inflammatory effect can significantly enhance the effectiveness of IANB, as acute inflammation can reduce anesthetic diffusion and hinder its analgesic action [33–35].

Therefore, taking NSAIDs before the anesthetic procedure can enhance the nerve block, promoting a more prolonged and complete response to local anesthesia and reducing the risk of anesthetic failure in patients with IP [36]. This integrated approach improves patient comfort, decreases the need for high anesthetic doses, and contributes to more effective pain management during and after dental treatment [37–40].

This systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the ID: CRD420251062710.

We searched databases such as Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and PubMed using the keywords “anti-inflammatory, alveolar nerve block, and pulpitis” to find studies related to this topic. Only English-language articles were considered, and the search was limited to the past ten years (2014–2024). In addition to the main electronic databases, a supplementary search was conducted in the international clinical trial registry ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) to identify ongoing, unpublished, or registered studies that might meet the inclusion criteria of this systematic review. At the time of the search, no registered clinical trials were found that met the eligibility criteria. This step was undertaken to ensure the comprehensiveness of the review and to minimize the risk of publication bias.

Articles that met the following inclusion criteria were double-blindly selected by the reviewers: (1) studies involving human participants; (2) clinical research, case studies, or randomized controlled trials (RCTs), examining the effectiveness of AIT in combination with truncular anaesthesia of the alveolar nerve in patients with IP. Reviews and meta-analyses, animal model studies, and in vitro experiments were excluded. Studies in patients with a diagnosis other than IP, studies not examining truncular anaesthesia, studies with inappropriate methodologies, or not reporting measurable results were excluded.

Table 1 shows the components of the PICOS criteria (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design) as well as their use in the evaluation.

The review was conducted using the PICOS criteria.

| PICO Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | Individuals with irreversible pulpitis in mandibular molars |

| Intervention (I) | AIT with NSAIDs, corticosteroids before treatment; truncular alveolar nerve anaesthesia |

| Comparison (C) | Truncular anaesthesia of the alveolar nerve without the use of AIT compared with different types of AIT one hour before truncular anaesthesia |

| Outcome (O) | Anaesthesia enhancement, improvement of pain control, reduction of anesthesia failure, reduction of pain intensity |

AIT: anti-inflammatory therapy; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

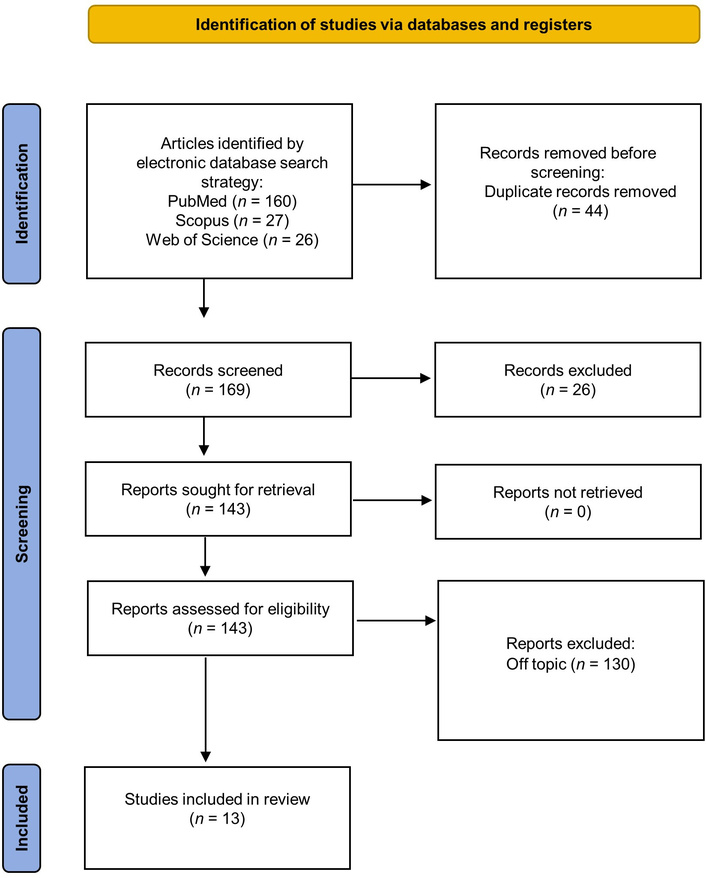

Three databases were searched, including 213 publications: PubMed (160), Web of Science (26), and Scopus (27). After 44 duplicate entries were removed, 169 records were screened for titles and abstracts, then 26 articles were removed one more. Following a full-text review, 130 papers were excluded for failing to meet the inclusion criteria. The selection process is summarized in PRISMA (Figure 3). A total of 13 publications, all of which are RCTs, were ultimately deemed suitable for qualitative analysis (Table 2).

Literature search Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram and database search indicators. Adapted from “PRISMA” (http://www.prisma-statement.org/). Accessed May 30, 2025. © 2024–2025 PRISMA Executive. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license.

Featured research in the qualitative analysis and its characteristics (all randomized controlled trials—RCTs).

| Author | Aim | Materials and methods | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singh SK, et al. 2024 [10] | To evaluate the effect of premedication on the success rate of IANB in tobacco-chewing (TC) patients with symptomatic IP. | 160 patients over 9 months were enrolled and divided into two main groups: smokers (study group) and non-smokers (control group). Each group was further split into two subgroups based on whether they received a premedication of 600 mg ibuprofen one hour prior to the procedure.All patients were administered a 2% lidocaine solution with epinephrine for the IANB. The success of pulpal anesthesia was confirmed using both electric pulp testing and cold spray application. Pain experienced during the NEI was measured on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS), with no reported pain indicating effective anesthesia. | The research demonstrated that taking ibuprofen before the procedure enhanced the effectiveness of the IANB in both TC and non-tobacco-chewing (NTC) patients. Despite this improvement being more pronounced in the NTC group, the difference in anesthetic success between the two groups was not statistically meaningful. Additionally, no definitive link could be drawn between nicotine use and the effectiveness of the premedication. |

| de Oliveira JP, et al. 2024 [39] | To investigate how preoperative use of ibuprofen and ibuprofen-arginine affects the success of IANB anesthesia in patients suffering from IP. It also examines how patients’ pain and anxiety levels before the procedure impact the effectiveness of the IANB. | 150 individuals with IP were randomly divided into three groups, each receiving a different treatment 30 minutes prior to the administration of IANB: 600 mg ibuprofen, 1,155 mg ibuprofen-arginine, or a placebo.Anxiety levels before the procedure were evaluated using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, and pain intensity was recorded using the Heft-Parker visual analog scale (HP VAS). | Patients who received ibuprofen showed a 62% success rate with the IANB, while those given ibuprofen-arginine had a higher rate of 78%. In contrast, only 34% of patients in the placebo group achieved successful anesthesia. Moreover, lower pre-treatment pain and anxiety were linked to improved anesthetic outcomes. |

| Bidar M, et al. 2017 [41] | To evaluate the effect of preoperative oral administration of ibuprofen or dexamethasone on the success rate of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. | 78 patients diagnosed with IP were randomly assigned to three groups (26 patients each): placebo, ibuprofen (400 mg), dexamethasone (4 mg).Medications were administered orally one hour prior to performing local anesthesia. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during the endodontic procedure. | The success rates of IANB were: placebo: 38.5%, ibuprofen: 73.1%, dexamethasone: 80.8%Both ibuprofen and dexamethasone significantly improved anesthetic success compared to placebo; however, no significant difference was observed between the two medications. |

| Riaz M, et al. 2023 [19] | To assess whether preoperative oral administration of analgesics (diclofenac sodium, piroxicam, or tramadol) enhances the efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars. | 120 patients with IP were randomly assigned to four groups:

Medications were administered orally one hour prior to IANB using 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Pain levels were measured using the HP VAS before and after anesthesia. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during the root canal procedure. | All analgesic groups demonstrated significantly higher IANB success rates compared to the control group (p < 0.05).Success rates were: piroxicam 93.3%, tramadol 86.6%, diclofenac sodium 66.6%, and control 30%.No significant difference was found among the three analgesic groups (p > 0.05).These findings suggest that preoperative administration of analgesics, particularly piroxicam, can enhance the efficacy of IANB in patients with IP. |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [36] | To compare the effects of preoperative administration of tramadol (50 mg and 100 mg), ibuprofen (600 mg), and a combination of ibuprofen (600 mg) with acetaminophen (1,000 mg) on the anesthetic efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. | Patients diagnosed with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars were randomly assigned to receive one of the following oral premedications:

Medications were administered one hour prior to performing the IANB using 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during endodontic access, assessed using the HP VAS. | Premedication with tramadol 100 mg significantly increased the success rate of IANB to 62% compared to the other groups (p < 0.05).The success rates for ibuprofen, ibuprofen/acetaminophen, and tramadol 50 mg groups were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.05).These findings suggest that a higher dose of tramadol (100 mg) as premedication can enhance the anesthetic efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. |

| Rodrigues GA, et al. 2024 [18] | To evaluate the impact of preemptive administration of dexamethasone (corticosteroid) and diclofenac potassium (NSAID) on the success rate of IANB anesthesia and on postoperative pain levels in patients undergoing endodontic treatment for mandibular molars with symptomatic IP. | 84 patients with symptomatic IP were randomly assigned to receive one of the following oral medications 60 minutes before IANB with 4% articaine (1:200,000 epinephrine):

Anesthetic success was assessed 15 minutes post-injection using a cold thermal test. Postoperative pain was evaluated at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours using a modified Numerical Rating Scale (mNRS). | Anesthetic success rates were significantly higher in the dexamethasone (39.3%) and diclofenac (21.4%) groups compared to the placebo group (3.6%) (p < 0.001).At 6 hours post-treatment, dexamethasone significantly reduced pain compared to placebo (p < 0.001), while diclofenac showed intermediate results without a significant difference from either dexamethasone or placebo.At 24, 48, and 72 hours, both dexamethasone and diclofenac groups experienced significantly lower pain levels compared to the placebo group (p < 0.001). |

| Fullmer S, et al. 2014 [33] | To evaluate whether preoperative administration of a combination of acetaminophen and hydrocodone enhances the anesthetic efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular posterior teeth. | 100 patients with symptomatic IP in a mandibular posterior tooth were randomly assigned to receive either:

Medications were administered orally 60 minutes prior to the administration of a conventional IANB. Endodontic access was initiated 15 minutes after the block. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during pulpal access or instrumentation, assessed using a VAS. | The success rate for the IANB was 32% in the acetaminophen/hydrocodone group and 28% in the placebo group.The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.662). These findings suggest that preoperative administration of 1,000 mg acetaminophen combined with 10 mg hydrocodone does not significantly improve the anesthetic efficacy of the IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. |

| Kumar U, et al. 2021 [42] | To evaluate whether preoperative administration of paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ketorolac enhances the anesthetic success of the IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. | 134 patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

Medications were administered orally one hour prior to performing the IANB using 2% lidocaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during access cavity preparation and canal instrumentation, assessed using the HP VAS. | The success rates of IANB were:Placebo: 29%Paracetamol: 33%Ketorolac: 43%No statistically significant difference was found among the three groups (p > 0.05).These findings suggest that preoperative administration of paracetamol or ketorolac does not significantly improve the anesthetic efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. |

| Hegde V, et al. 2023 [30] | To compare the anesthetic success of IANBs using 2% lidocaine in mandibular molars with symptomatic IP following preoperative oral administration of prednisolone, dexamethasone, ketorolac, or placebo. | 184 patients diagnosed with IP in mandibular molars were randomly assigned to receive one of the following oral medications 60 minutes before IANB:

The success of anesthesia was clinically confirmed when pain was absent during endodontic access or instrumentation. | The success rates of IANB were:

All three medications significantly increased anesthetic success compared to placebo (p < 0.05), with no significant differences among the active treatment groups. |

| Saha SG, et al. 2016 [16] | To evaluate the impact of preoperative oral administration of ketorolac (10 mg), diclofenac potassium (50 mg), or placebo on the anesthetic efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. | 150 adult patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis in mandibular molars. Participants were randomly assigned to three groups receiving, one hour before inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) with 2% lidocaine and epinephrine:

Pain during cavity preparation and canal instrumentation was assessed using the modified Heft-Parker visual analog scale (VAS), with anesthetic success defined as no pain or only mild pain. | All patients showed a significant reduction in pain after the IANB. However, anesthetic success was highest in the Ketorolac group, followed by the Diclofenac group, with the placebo group showing the lowest success. The study concluded that oral premedication with 10 mg Ketorolac significantly increases the likelihood of achieving effective anesthesia in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [43] | To evaluate the impact of preoperative oral administration of meloxicam, ketorolac, dexamethasone, or ibuprofen on the anesthetic success of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars. | 250 emergency patients with symptomatic IP in a mandibular first or second molar were randomly assigned to receive one of the following oral medications 60 minutes before IANB:

Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during access cavity preparation and root canal instrumentation, measured using the HP VAS. | The success rates for IANB were:

All active premedications significantly improved anesthetic success compared to placebo (p < 0.05), with no significant differences among the active treatment groups (p > 0.05). These findings suggest that preoperative administration of meloxicam, ketorolac, dexamethasone, or ibuprofen enhances the efficacy of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. |

| Nivedha V, et al. 2020 [45] | To assess the effectiveness of preoperative oral ketorolac tromethamine in managing intraoperative and postoperative pain during single-visit root canal treatment of mandibular molars with acute IP. | 126 patients with acute IP received 10 mg of oral ketorolac tromethamine prior to local anesthesia. Two local anesthetics were used: 2% lignocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline and 4% articaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline. Three irrigation solutions were employed: saline, 3% sodium hypochlorite, and dexamethasone. Intraoperative pain was measured using VAS, and postoperative pain incidence was recorded. | Mean intraoperative pain scores were similar between the lignocaine (4.33 ± 2.58) and articaine (4.22 ± 2.88) groups.Postoperative pain incidence was significantly lower in the lignocaine group (16.7%) compared to the articaine group (49.2%) (p = 0.000).Preoperative ketorolac did not significantly reduce intraoperative pain but was effective in controlling postoperative pain when used with lignocaine anesthesia.These findings suggest that while preoperative ketorolac may not impact intraoperative pain levels, it can effectively reduce postoperative pain, particularly when combined with lignocaine as the local anesthetic. |

| Aggarwal V, et al. 2021 [44] | To evaluate the effect of preoperative intraligamentary injections of dexamethasone or diclofenac sodium on the anesthetic efficacy of 2% lidocaine administered via IANB in patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars. | 117 patients with symptomatic IP in mandibular molars were randomly assigned to receive an intraligamentary injection of one of the following solutions:

Thirty minutes after the intraligamentary injection, all patients received an IANB using 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine. Anesthetic success was defined as no or mild pain during root canal access preparation and instrumentation, assessed using the HP VAS. | The anesthetic success rates were:

The dexamethasone group demonstrated a significantly higher success rate compared to both the diclofenac sodium and control groups (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the diclofenac sodium and control groups. These findings suggest that preoperative intraligamentary injection of dexamethasone can significantly enhance the anesthetic success of IANB with 2% lidocaine. |

TC: tobacco-chewing; NTC: non-tobacco-chewing; IANB: inferior alveolar nerve block; NEI: needle electrode insertion; IP: Irreversible pulpitis; VAS: visual analog scale; HP VAS: Heft-Parker visual analog scale; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

As part of the screening process, which involved reviewing the titles and abstracts of the articles selected in the previous identification step, the full texts of the included publications were examined after excluding those that did not address the topics under investigation.

Using ROBINS, a tool designed to assess the risk of bias in the results of non-randomized studies comparing the health effects of two or more interventions, three reviewers—AS, LPZ, FED—evaluated the quality of the included publications. Each of the seven assessed criteria was assigned a level of bias (Table 3). In addition, for all RCTs, the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (ROB 2.0) tool to ensure a comprehensive and appropriate evaluation of study quality based on study design (Table 4).

Bias Assessment by the ROB 1.0 tool.

| Author | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singh SK, et al. 2024 [10] | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + |

| de Oliveira JP, et al. 2024 [39] | × | + | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| Bidar M, et al. 2017 [41] | - | + | × | + | - | × | - | - |

| Riaz M, et al. 2023 [19] | - | + | - | + | × | - | + | - |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [36] | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | - |

| Rodrigues GA, et al. 2024 [18] | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| Fullmer S, et al. 2014 [33] | × | - | × | - | × | + | - | - |

| Kumar U, et al. 2021 [42] | × | - | - | - | + | + | + | × |

| Hegde V, et al. 2023 [30] | + | - | + | + | × | + | - | - |

| Saha SG, et al. 2016 [16] | - | × | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [43] | + | + | + | - | + | × | + | + |

| Nivedha V, et al. 2020 [45] | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + |

| Aggarwal V, et al. 2021 [44] | - | + | × | - | - | + | + | - |

D1: bias due to confounding; D2: bias arising from measurement of the exposure; D3: bias in selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis); D4: bias due to post-exposure interventions; D5: bias due to missing data; D6: bias arising from measurement of the outcome; D7: bias in selection of the report result. Red ×: high; yellow -: some concerns; green +: low.

Risk of bias (ROB 2.0).

| Study | D1Randomization | D2Deviations | D3Missing data | D4Outcome measurement | D5Selective reporting | Overall judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singh SK, et al, 2024 [10] | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| de Oliveira JP, et al. 2024 [39] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bidar M, et al. 2017 [41] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Riaz M, et al. 2023 [19] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [36] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rodrigues GA, et al. 2024 [18] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fullmer S, et al. 2014 [33] | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Kumar U, et al. 2021 [42] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hegde V, et al. 2023 [30] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Saha SG, et al. 2016 [16] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Elnaghy AM, et al. 2023 [43] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nivedha V, et al. 2020 [45] | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Aggarwal V, et al. 2021 [44] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Yellow -: some concerns; green +: low.

A GRADE assessment was conducted to evaluate the overall certainty of the evidence for the main outcomes analyzed in this review. The outcome “success rate of IANB” following preoperative administration of NSAIDs or corticosteroids was supported by RCTs with mostly low to moderate risk of bias. However, inconsistency across drug types, dosages, and outcome definitions introduced some imprecision. Based on these factors, the certainty of evidence for this outcome was rated as moderate. Similarly, evidence for the reduction in postoperative pain after premedication with anti-inflammatory drugs was also judged to have moderate to high certainty. These ratings suggest that current findings are likely to reflect true effects, although further high-quality trials may impact future estimates.

Full details of the GRADE evaluation are presented in Table 5.

GRADE summary table—certainty of evidence.

| Outcome | No. of studies (RCTs) | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IANB success rate (NSAIDs vs. Placebo) | 13 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| IANB success rate (Corticosteroids vs. Placebo) | 6 | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| IANB success (NSAIDs vs. Corticosteroids) | 4 | + | × | + | × | - | + |

| Postoperative pain reduction | 5 | + | + | + | - | + | - |

Red ×: high; yellow -: some concerns; green +: low. RCTs: randomized controlled trials; IANB: inferior alveolar nerve block; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

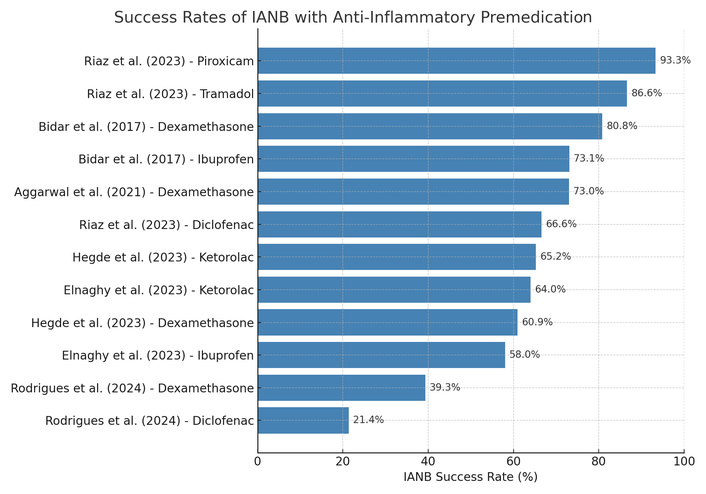

To facilitate visual comparison across studies, a summary chart was developed illustrating the reported IANB success rates for each pharmacological agent. Figure 4 displays the relative effectiveness of NSAIDs and corticosteroids as preoperative medications compared to placebo. Although a meta-analysis was not feasible due to methodological heterogeneity, this visual summary highlights consistent improvements in anesthetic success with anti-inflammatory premedication.

Comparative success rates (%) of IANB following premedication with different anti-inflammatory agents across the included randomized controlled trials. The chart illustrates a consistent advantage of NSAIDs and corticosteroids over placebo. IANB: inferior alveolar nerve block; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In recent years, the management of anesthesia in patients with symptomatic IP has become one of the most complex clinical challenges in endodontics. In particular, the IANB, although the anesthetic technique of choice for mandibular molars, shows high failure rates in patients with IP. In this context, numerous studies have evaluated the effectiveness of pharmacologic premedication as a strategy to increase anesthetic success.

The most studied drug is undoubtedly ibuprofen. In several studies, including those by de Oliveira et al. [39], Bidar et al. [41], and Riaz et al. [19], preoperative administration of ibuprofen significantly improved the success of IANB. De Oliveira compared 600 mg ibuprofen, an ibuprofen-arginine formulation, and a placebo, reporting anesthetic success rates of 78% in the ibuprofen-arginine group, 62% with pure ibuprofen, and only 34% in the control group. Another study by Saha et al. [16] concluded that oral premedication with 10 mg Ketorolac significantly increases the likelihood of achieving effective anesthesia in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis.

Ibuprofen combined with other analgesics has also shown promising results. Elnaghy et al. [36] compared tramadol, ibuprofen, and a combination of ibuprofen/acetaminophen, finding a success rate of 62% in patients premedicated with 100 mg of tramadol, indicating a significant improvement in anesthetic efficacy. Conversely, no statistically significant differences were observed among the other groups. These data suggest that the ibuprofen/acetaminophen combination may offer slightly greater efficacy, possibly due to the complementary mechanisms of action. Other studies have evaluated alternative NSAIDs. Kumar et al. [42] compared 650 mg paracetamol and 10 mg ketorolac, reporting success rates of 43% for ketorolac and 33% for paracetamol, versus 29% in the control group. Elnaghy et al. [43] also included meloxicam (7.5 mg), ketorolac (10 mg), ibuprofen (600 mg), and dexamethasone (0.5 mg) in a direct comparison. In this study, all treatment groups achieved higher results than the control, with anesthetic success ranging from 52% to 64%, while the placebo group showed only 32%.

The use of corticosteroids as premedication is receiving increasing attention. Rodrigues et al. [18] compared dexamethasone (4 mg), diclofenac potassium (50 mg), and placebo. The dexamethasone group achieved a success rate of 39.3%, higher than both the diclofenac group (21.4%) and the control group (3.6%). Similarly, Hegde et al. [30] compared dexamethasone with prednisolone and placebo, reporting success rates of 60.86% and 56.52% in the treated groups, versus 21.73% in the control group. Aggarwal et al. [44] also showed that a single intraligamentary injection of 4 mg/mL dexamethasone significantly improved the effectiveness of lidocaine anesthesia, with a success rate of 73% compared to 32% in the placebo group. These results support the idea that corticosteroids, due to their potent anti-inflammatory action, may be useful in cases of acute pain and deep inflammation, such as IP.

In addition to NSAIDs and corticosteroids, some studies have evaluated combinations with opioids or centrally acting analgesics. Fullmer et al. [33] tested the effect of acetaminophen/hydrocodone (1,000 mg/10 mg), reporting a success rate of 32% compared with 28% in the placebo group, with the difference between the two groups not being statistically significant.

Nivedha et al. [45] studied the effectiveness of 10 mg ketorolac combined with different local anesthetics and irrigants. Although the benefit was more evident in postoperative pain control than in the intraoperative phase, IANB effectiveness also improved, particularly when ketorolac was combined with lidocaine and epinephrine.

One of the most interesting aspects concerns the study by Singh et al. [10], which evaluated the effectiveness of ibuprofen premedication in patients who chew tobacco. Although the drug was effective in both groups, the success rate was slightly lower in chewing tobacco users, suggesting a potential influence of chronic nicotine consumption on anesthetic response. However, the difference was not statistically significant, but it opens avenues for future research.

Despite encouraging results, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the included studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity in terms of drug types, dosages, and timing of administration, which limited the possibility of conducting a quantitative synthesis and affected the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the definitions of anesthetic success varied across studies (e.g., different pain assessment scales, success thresholds, and procedural endpoints), introducing a risk of indirectness in the comparison of outcomes.

Second, some studies did not report essential statistical measures such as standard deviations or confidence intervals, or error margins for their outcomes, reducing the ability to assess internal consistency and reliability of the findings, and limiting the feasibility of conducting a meta-analysis. Only a few trials, such as that by Nivedha et al. [45], included standard deviations alongside mean pain scores; most studies did not.

Additionally, the potential for publication bias cannot be excluded, especially considering that no eligible unpublished or ongoing studies were found during the search of trial registries. Some trials lacked information on blinding or allocation concealment, potentially introducing performance or detection bias.

Lastly, the quality assessment using tools such as ROBINS revealed a variable risk of bias, underscoring the need for careful interpretation of the results.

Future high-quality RCTs with standardized methodologies and transparent statistical reporting are necessary to confirm and refine the current evidence.

Overall, the data clearly indicate that premedication with NSAIDs or corticosteroids (particularly NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, ketorolac, diclofenac, and piroxicam, as well as corticosteroids like dexamethasone and prednisolone) significantly improves the success of IANB in patients with symptomatic IP. Success rates in treated groups generally range between 55% and 73%, while control groups rarely exceed 40%. The choice of drug, dosage, route of administration, and the patient’s clinical condition (including behavioral factors) can influence the outcome, but the benefit of premedication is now well documented. The growing body of evidence suggests that the use of pharmacological premedication should be considered to improve intraoperative comfort and reduce the need for supplemental anesthesia.

The management of anesthesia in patients with symptomatic IP represents a significant challenge in endodontic practice, particularly due to the low efficacy of the IANB in cases of acute pulpal inflammation [39, 40, 46–48]. The reviewed data consistently demonstrate that pharmacological premedication, whether with NSAIDs or corticosteroids, can significantly improve the anesthetic success rate of the IANB in patients with symptomatic IP, reducing intraoperative pain and the need for supplemental anesthesia. Among NSAIDs, ibuprofen—especially when combined with other analgesics like acetaminophen—has proven to be one of the most effective options, showing success rates markedly higher than placebo. Other NSAIDs, such as ketorolac and meloxicam, have also shown promising results. Corticosteroids, particularly dexamethasone, have shown comparable or even superior efficacy to NSAIDs, likely due to their potent anti-inflammatory properties [44]. Although some individual factors, such as nicotine use, may slightly influence the response to premedication, the overall effect remains positive. These findings support the systematic integration of pharmacological premedication into endodontic protocols for patients with symptomatic IP, with the aim of optimizing anesthetic effectiveness and improving the patient’s clinical experience.

Further RCTs with consistent reporting of outcome variability (e.g., standard deviations and confidence intervals) are needed to enable stronger quantitative comparisons.

AIT: anti-inflammatory therapy

HP VAS: Heft Parker Visual Analog Scale

IANB: inferior alveolar nerve block

IP: irreversible pulpitis

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NTC: no tobacco chewing

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

TC: tobacco chewing

VAS: visual analog scale

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used the Adobe Firefly tool to create Figures 1 and 2. After using the tool, authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

ADI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. GM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. LPZ: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Supervision. AS: Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. FED: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. FI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. GMT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. MDF: Methodology, Data curation, Supervision. AP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. DDV: Validation, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Project administration. AMI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. GD: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The primary data for this systematic review were sourced online from databases listed in the methods. Referenced articles are accessible on Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed. Additional supporting data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 602

Download: 21

Times Cited: 0