Affiliation:

1Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Igdir University, 76000 Igdir, Turkey

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-7227-9182

Affiliation:

1Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Igdir University, 76000 Igdir, Turkey

2Department of Electronics and Information Technologies, Faculty of Architecture and Engineering, Nakhchivan State University, Nakhchivan AZ 7012, Azerbaijan

Email: ishakpacal@igdir.edu.tr

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6670-2169

Explor Med. 2025;6:1001377 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2025.1001377

Received: September 27, 2025 Accepted: November 01, 2025 Published: December 11, 2025

Academic Editor: Michaela Cellina, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Artificial Intelligence in Precision Imaging: Innovations Shaping the Future of Clinical Diagnostics

Aim: Early and accurate diagnosis of brain tumors is critical for treatment success, but manual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) interpretation has limitations. This study evaluates state-of-the-art Transformer-based architectures to enhance diagnostic efficiency and robustness for this task, aiming to identify models that balance high accuracy with computational feasibility.

Methods: We systematically compared the performance and computational cost of eleven models from the Vision Transformer (ViT), Data-efficient Image Transformer (DeiT), and Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows (Swin) Transformer families. A publicly available four-class MRI dataset (Glioma, Meningioma, Pituitary, No Tumor) was used for multi-class classification. The dataset was partitioned using stratified sampling and extensively augmented to improve model generalization.

Results: All evaluated models demonstrated high accuracy (> 98.8%). The Swin-Small and Swin-Large models achieved the highest accuracy of 99.37%. Remarkably, Swin-Small delivered this top-tier performance at a fraction of the computational cost of the Swin-Large model, which is nearly four times its size and with more than double the inference speed (0.54 ms vs. 1.29 ms), showcasing superior operational efficiency.

Conclusions: The largest model does not inherently guarantee the best performance. Architecturally efficient, mid-sized models like Swin-Small provide an optimal trade-off between diagnostic accuracy and practical clinical applicability. This finding highlights a key direction for developing feasible and effective AI-based diagnostic systems in neuroradiology.

Brain tumors, which are formed by the irregular and uncontained growth of cells in brain tissue, are very serious neurological disorders that put critical and cognitive functions of a patient at risk [1, 2]. No matter the benign or malignant nature of the tumor masses, the effectiveness of any treatment regimen will ultimately depend on an accurate and early diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides clinicians with a visible template of brain anatomy with high resolution, and is considered the gold standard for detecting, localizing, and measuring tumors [3, 4]. Manual interpretation of an MRI offers serious drawbacks due to features like cancerʼs intrinsic morphological heterogeneity, as well as morphological diversity, indistinct margins, and the masses often appearing with similar intensity to healthy tissue [5–7]. Therefore, the diagnostic process relies heavily on specialist ability, while its variability in subsequent diagnosis makes it difficult, unintuitive, and prone to human error [8–10]. Added to this, there has been a formal decline in the efficiency of human interpretation, especially as it relies heavily on large datasets, which further establishes the very real and increasing need for fully automated deep learning-based tumor detection and classification [11].

The integration of artificial intelligence-based approaches into medical image analysis has sparked a paradigm shift in radiological and pathological evaluation [12–15]. By autonomously learning hierarchical features from raw pixel data, these computational systems offer the potential to minimize inter-observer variability and discover quantitative biomarkers that go beyond qualitative assessments [16–19]. The clinical validity of these technologies has been demonstrated across a wide range of applications, from the segmentation of neoplastic tissues in oncologic imaging to the detection of microvascular anomalies in fundoscopic images and the analysis of histopathological slides in digital pathology [20–23]. These achievements highlight the potential of AI to evolve from merely a diagnostic support tool into a fundamental component of precision medicine [24–26].

This study is based on the premise that we can move past the inductive biases associated with traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), particularly the locality constraint of convolutional kernels [27, 28]. This study takes advantage of state-of-the-art Transformer models that can model global context and long-range pixel dependencies in large-scale image data, and have established Transformers as a viable and compelling alternative solution to CNNs in areas like radiology and pathology [29–31]. Based on the remarkable performance of Vision Transformer (ViT)-based algorithms at detecting, classifying, and segmenting lesions from mammograms, histopathology slides, and ultrasound images in breast cancer imaging, we study and systematically compare the top Transformer models, ViT, Data-efficient Image Transformer (DeiT), and Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows (Swin) Transformer, through all four architectural scales (ʻtinyʼ, ʻsmallʼ, ʻbaseʼ, and ʻlargeʼ), using the task of brain MRI classification. Our analysis investigates and compares diagnostic accuracy, performance, and overall success across different model architectures.

While the aforementioned studies have individually advanced the application of Transformers in neuro-oncology, our work provides a distinct contribution by conducting a comprehensive, head-to-head comparative analysis. This study distinguishes itself from the existing literature in three key aspects:

Unlike studies that focus on a single novel architecture or hybrid model, we systematically evaluate eleven models from three foundational Transformer families (ViT, DeiT, and Swin) across four distinct architectural scales (ʻtinyʼ, ʻsmallʼ, ʻbaseʼ, and ʻlargeʼ). This broad-spectrum analysis offers a panoramic view of the current landscape, allowing for direct and standardized comparisons of their capabilities on a unified task.

While prior works have primarily targeted incremental improvements in accuracy, a central aim of our investigation is to elucidate the critical trade-off between diagnostic performance and computational efficiency [parameters and giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs)]. By demonstrating that a mid-sized model like Swin-Small can match the accuracy of a model nearly four times its size, we highlight a crucial consideration for practical clinical deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Our study moves beyond reporting performance metrics by integrating a qualitative analysis using Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) for both high- and low-performing models. This dual approach provides a deeper understanding of why certain models perform better, linking quantitative success to the qualitative ability of the model to learn and focus on clinically salient features, thereby strengthening the argument for its trustworthiness as a diagnostic aid.

Recent advancements in medical image analysis have increasingly highlighted the limitations of traditional CNNs in modeling long-range dependencies, paving the way for the adoption of Transformer-based architectures. Within the domain of brain tumor classification, a variety of studies have explored this paradigm shift by introducing innovative hybrid models and optimization strategies. Goceri [32] developed a CNN-Transformer hybrid framework that effectively balances local texture extraction with global contextual modeling, achieving strong performance in both glioma grading and multi-class tumor recognition. In a similar vein, Tanone et al. [33] investigated feature optimization pipelines grounded in ViTs. Tanoneʼs ViT-CB framework employed principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, subsequently utilizing a CatBoost classifier and SHAP-based explainability to strengthen interpretability. Complementing these efforts, Wang et al. [34] introduced RanMerFormer, which incorporates a pre-trained ViT backbone but applies token merging to eliminate redundant feature vectors, substantially improving computational efficiency while preserving robust representational capabilities. Collectively, these approaches reflect a growing consensus that classification accuracy and interpretability can be advanced not only through architectural novelty but also through carefully designed feature selection and dimensionality reduction strategies.

In parallel, the task of brain tumor segmentation has witnessed rapid innovation through the integration of Transformers into U-shaped architectures, as researchers aim to combine the hierarchical feature extraction power of CNN encoders with the global dependency modeling of Transformers. Zhang et al. [35] proposed AugTransU-Net, which enriches bottleneck representations through Augmented Transformer modules with circulant projections, thereby enhancing feature diversity at deeper layers. Extending this concept further, Zhang et al. [36] introduced ETUnet, an enhanced U-Net that fuses CNN-Transformer hybrids in the encoder, incorporates spatial-channel attention in the bottleneck to optimize global interactions, and integrates cross-attention mechanisms into skip connections to refine boundary localization. Meanwhile, Pan et al. [37] targeted volumetric segmentation challenges with VcaNet, which supplements a U-Net structure with 3D convolutional encoders, a ViT bottleneck to capture global volumetric dependencies, and a convolutional block attention module (CBAM)-based decoding to improve feature fusion. Together, these works demonstrate a decisive trajectory toward hybrid models that leverage the complementary strengths of CNNs and Transformers, yielding state-of-the-art outcomes in the complex and clinically significant task of brain tumor segmentation.

The data infrastructure for this research is referred to as the “Brain Tumor MRI Dataset”, which consists of a dataset created by Ahmed Sorour that is publicly available on Kaggle [38]. This dataset is a source of reference material for brain tumor classification and includes three common tumor classes: Glioma, Meningioma, and Pituitary. There is also a control group consisting of healthy brain MRIs with no tumor. There is a total of 5,249 T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced MRI slices that are noted as to their pathological state or normal. Figure 1 includes samples of the classes to illustrate the types of data included in the dataset.

To facilitate objective model training, validation, and performance testing, the dataset was partitioned into three subsets using a stratified sampling method. This technique minimizes potential model bias by ensuring that the proportional representation of each class in the subsets mirrors that of the original dataset. Accordingly, 70% of the data (3,673 images) were allocated for training, 15% (786 images) for validation, and the remaining 15% (790 images) for testing. While the training set was used to optimize model parameters, the validation set played a critical role in monitoring the modelʼs generalization ability, tuning hyperparameters, and preventing overfitting to select the best-performing model during the training process. The test set, kept entirely separate from the training and validation phases, was reserved for the final, unbiased evaluation of the modelsʼ performance on previously unseen data. A detailed breakdown of the datasetʼs distribution by class and subset is presented in Table 1.

Distribution of dataset by classes and sections.

| Classes | Training | Validation | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma | 902 | 193 | 194 | 1,289 |

| Meningioma | 1,112 | 238 | 239 | 1,589 |

| No tumor | 567 | 121 | 123 | 811 |

| Pituitary | 1,092 | 234 | 234 | 1,560 |

| Total | 3,673 | 786 | 790 | 5,249 |

To effectively train the Transformer architectures for an image classification task, the original dataset required a meticulous preprocessing and restructuring workflow. Initially, the dataset was provided in an object detection format, accompanied by text files (*.txt) containing bounding box coordinates for each image in compliance with the You Only Look Once (YOLO) format. As this structure was incompatible with the studyʼs semantic classification objective, these coordinate files were systematically discarded. Following this step, the existing train and validation directories were consolidated. The resulting data pool was then re-partitioned into three independent subsets: training, validation, and test using stratified sampling, adhering to the distribution detailed in Table 1.

An exhaustive data augmentation approach was applied solely to the training set to assist the modelʼs generalization ability and reduce overfitting risk [39, 40]. The augmentation approach was deliberately designed to have the model learn robust features that would remain invariant to morphology, position, and intensity, all of which can be noted through clinical application. Therefore, each training image underwent random resized cropping, meaning a portion (between 8–100%) of the original image could be sampled, and rescaled to the target size of 224 × 224 pixels to ensure the model was invariant to scale and position. A random horizontal flip was applied with a 50% probability to further improve the modelʼs insensitivity to orientational symmetry. Each training image was also additionally perturbed by photometric methods using colour jitter [28] of magnitude 0.4, to develop the modelʼs insensitivity to lighting and contrast variation due to differences in MRI acquisition conditions. In addition to the data level augmentation, a model level regularization, label smoothing [30], and a smoothing factor of 0.1 were applied to avoid overconfidence when predicting and to better calibrate the model. In order to be rigorous, these augmentation and regularization procedures were not applied to the validation or test datasets when evaluating performance.

The field of computer vision has been fundamentally reshaped by the integration of Transformer architecture, a paradigm initially developed for natural language processing. A vanguard of this movement is the ViT [41], which proposes a radical departure from conventional image analysis. Instead of leveraging the spatially localized inductive biases of convolutional filters, ViT re-conceptualizes an image as a sequence of flattened, non-overlapping patches, or tokens. This reformulation allows for the application of a global self-attention mechanism, granting the model an unparalleled capacity to capture long-range spatial dependencies across the entire image canvas and thereby develop a holistic representation. However, this architectural freedom comes at a steep price: the unconstrained nature of global attention incurs a computational complexity that scales quadratically with the number of image patches, presenting substantial hurdles for model scalability and rendering it notoriously data-hungry, especially when trained on datasets of limited scale.

To surmount the challenge of data-intensive training inherent in the foundational ViT model, the DeiT [42] was introduced. DeiT leverages a sophisticated knowledge distillation framework wherein a more compact “student” Transformer is trained to emulate the inferential behavior of a pre-trained, higher-capacity “teacher” model, which may be either a state-of-the-art CNN or a larger Transformer. This is operationalized through the introduction of a dedicated distillation token, which is processed in parallel with the standard class token. The optimization objective is a composite loss function, combining a standard cross-entropy loss for classification with a distillation-specific loss that penalizes divergence between the studentʼs distillation token output and the teacherʼs predictions. This teacher-guided regularization strategy proves remarkably effective, enabling DeiT to attain performance metrics on par with or even exceeding ViT, while notably obviating the necessity for pre-training on massive, proprietary image corpora.

Concurrently, the Swin Transformer [43] emerged to specifically tackle the computational and scalability impediments of ViTʼs global attention. Its principal innovation is a hierarchical architecture that constrains the self-attention computation to local, non-overlapping windows, thereby achieving a computational complexity that scales linearly with the input image size. To facilitate cross-window information exchange and progressively construct a global receptive field, the Swin Transformer integrates a shifted window mechanism across successive layers. This synergistic operation of local attention and window shifting culminates in the generation of multi-scale, hierarchical feature representations, analogous to the feature pyramids integral to modern CNN architectures. This design renders the Swin Transformer exceptionally proficient for dense prediction tasks, including object detection and semantic segmentation. Collectively, these pioneering architectures do not merely offer incremental improvements; they signify a decisive pivot from convolution-dominated paradigms, charting a new and influential trajectory for the future of advanced visual recognition.

The entire suite of model training and evaluation protocols was executed on a high-performance computing workstation operating under the Ubuntu 24.04 environment. The systemʼs hardware architecture comprised an Intel Core i9-14900K central processing unit, complemented by 64 GB of DDR5 random-access memory to facilitate efficient data manipulation and preprocessing. To address the computationally demanding nature of deep learning tasks, the workstation was outfitted with a high-performance NVIDIA RTX 5090 graphics processing unit, capitalizing on its 24 GB of GDDR6X memory to substantially accelerate both the training and inference phases. The software framework was established upon Python 3.13 and PyTorch 2.9, while leveraging the NVIDIA CUDA Toolkit 13.1 and associated cuDNN libraries to ensure optimized GPU performance within contemporary deep learning paradigms.

For a quantitative evaluation of the diagnostic efficacy of the classification models, a conventional set of performance metrics was utilized to conduct a thorough analysis of their predictive accuracy and generalization capabilities. The sensitivity, also referred to as recall, assesses the modelʼs proficiency in accurately identifying the complete set of true positive instances. In contrast, precision evaluates the fidelity of a positive prediction by determining the fraction of positive classifications that were verifiably correct. To provide a balanced measure, the F1-score is computed as the harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity, which is an especially critical indicator when dealing with the class imbalances frequently encountered in medical imaging datasets. Finally, accuracy furnishes a holistic view of the modelʼs performance by representing the proportion of all correctly identified instances relative to the entire dataset. As detailed in Equations 1–4, the mathematical formulations for these metrics are predicated on the quantities of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN).

All models were trained for 300 epochs using the AdamW optimizer with a weight decay of 0.05. A cosine annealing schedule was employed to dynamically adjust the learning rate, starting from an initial value of 1e-4 and progressively decreasing to 1e-6. This strategy facilitates efficient convergence during the initial training phases while allowing for fine-tuning as the models approach optimal performance. A consistent batch size of 16 was utilized across all experiments to ensure stable and comparable training dynamics. The training process was expedited by leveraging mixed-precision capabilities, which reduces the memory footprint and computational overhead without compromising model efficacy. To ensure the selection of the most generalizable model, the weights corresponding to the epoch with the highest validation accuracy were saved for subsequent evaluation on the independent test set.

The comparative analysis of eleven Transformer-based models revealed a consistently high level of performance across all architectures for the multi-class brain tumor classification task. As detailed in Table 2, every model achieved a test accuracy exceeding 98.8%, underscoring the profound capability of Transformer architectures to learn discriminative pathological features from brain MRI scans.

Performance metrics and computational costs of the models on the test dataset (GPU: RTX 5090, Batch-size 16).

| Models | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs | Inference time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swin-Tiny | 98.86 | 98.93 | 98.73 | 98.83 | 27.52 | 8.7422 | 0.32 |

| Swin-Small | 99.37 | 99.47 | 99.35 | 99.41 | 48.84 | 17.0885 | 0.54 |

| Swin-Base | 98.86 | 99.03 | 98.66 | 98.84 | 86.75 | 30.3375 | 0.81 |

| Swin-Large | 99.37 | 99.45 | 99.28 | 99.36 | 195.0 | 68.1649 | 1.29 |

| ViT-Tiny | 98.99 | 99.01 | 98.96 | 98.99 | 5.52 | 2.1569 | 0.12 |

| ViT-Small | 98.86 | 98.93 | 98.76 | 98.84 | 21.67 | 8.4968 | 0.23 |

| ViT-Base | 98.86 | 98.90 | 98.74 | 98.82 | 85.8 | 33.7257 | 0.56 |

| ViT-Large | 99.24 | 99.32 | 99.17 | 99.24 | 303.3 | 119.3714 | 1.76 |

| DeiT-Tiny | 98.99 | 99.01 | 98.96 | 98.98 | 5.52 | 2.1569 | 0.12 |

| DeiT-Small | 99.11 | 99.14 | 99.07 | 99.10 | 21.67 | 8.4968 | 0.23 |

| DeiT-Base | 98.99 | 99.01 | 98.86 | 98.93 | 85.8 | 33.7257 | 0.56 |

GFLOPs: giga floating-point operations per second.

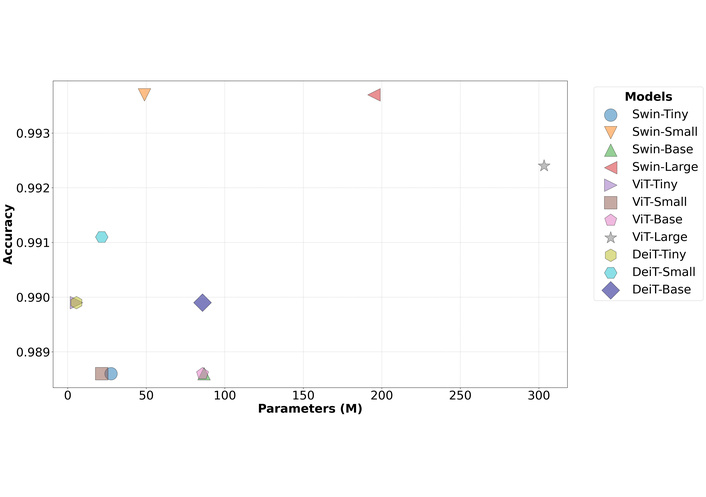

The pinnacle of classification accuracy was achieved by the Swin-Small and Swin-Large models, both attaining an accuracy of 99.37%. These were closely followed by ViT-Large with 99.24% and DeiT-Small with 99.11% accuracy. A critical finding emerged from the performance-efficiency trade-off analysis. While Swin-Large and Swin-Small demonstrated identical accuracy, the Swin-Large model required nearly four times the parameters (195.0M vs. 48.84M), four times the computational expenditure (68.16 GFLOPs vs. 17.09 GFLOPs), and exhibited more than double the inference latency (1.29 ms vs. 0.54 ms) to achieve this result. This suggests diminishing returns on performance with increased model scaling for this specific task. The Swin-Small architecture is therefore highlighted as a particularly noteworthy model, delivering peak performance at a substantially lower computational cost. This critical trade-off between model size and diagnostic performance, which underscores the exceptional efficiency of the Swin-Small architecture, is visually represented in Figure 2.

Comparison of model test accuracy versus the number of parameters (M). Swin: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows; ViT: Vision Transformer; DeiT: Data-efficient Image Transformer.

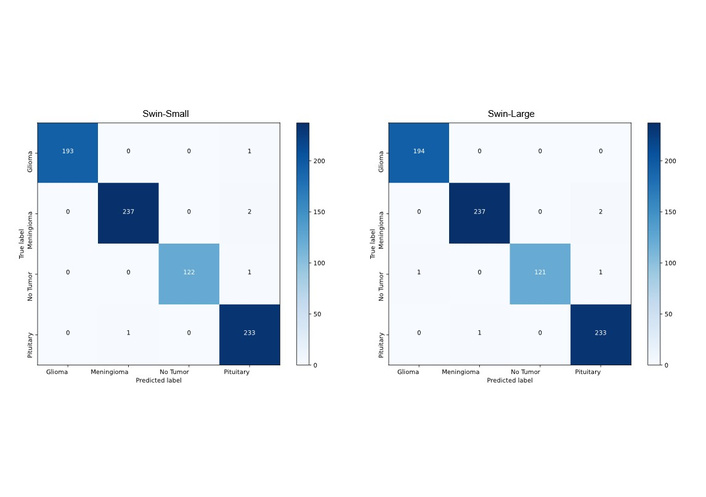

Similarly, the DeiT-Small model demonstrated exceptional efficiency, achieving a higher F1-score (99.10) than the much larger ViT-Base and Swin-Base models with only a fraction of the parameters (21.67M). The confusion matrices for the top-performing Swin-Small and Swin-Large models (Figure 3) further confirm their robustness, showing minimal misclassifications across all four categories.

Confusion matrices of Swin-Small (left) and Swin-Large (right) architectures. Swin: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows.

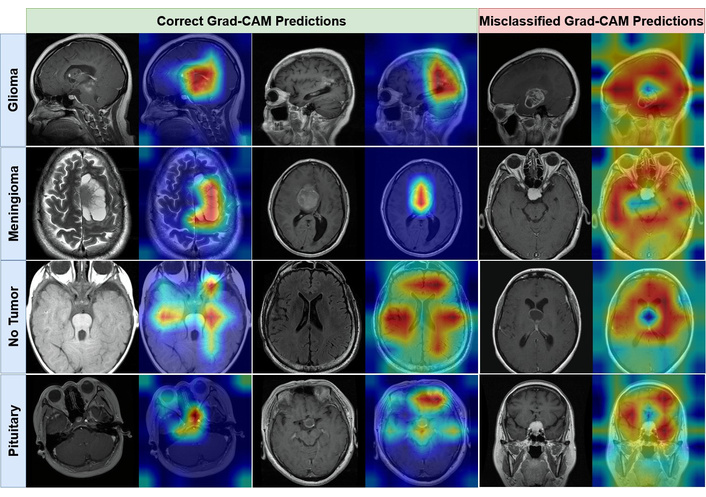

To move beyond quantitative metrics and gain insight into the models' decision-making processes, we employed Grad-CAM for visual explanation. The analysis was focused on our most efficient, top-performing model, Swin-Small. The generated heatmaps visualize the pixel regions that the model deemed most salient for its predictions.

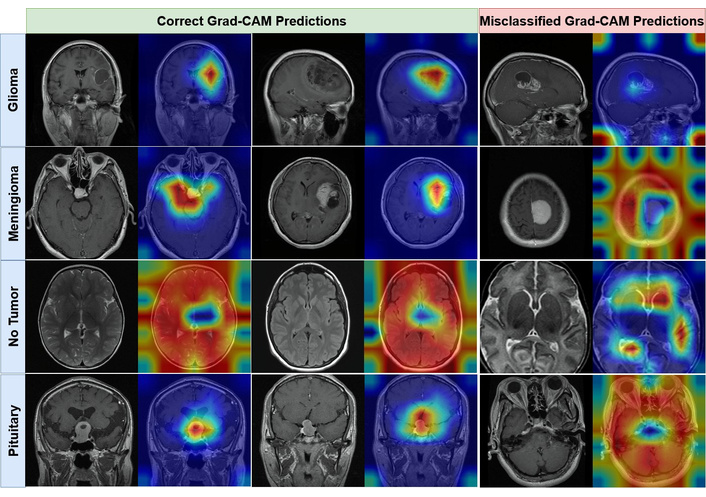

As illustrated in Figure 4, the Grad-CAM visualizations demonstrate that the Swin-Small model consistently focuses its attention on pathologically relevant areas. For all three tumor classes, the activation maps are precisely localized over the tumorous masses, largely ignoring surrounding healthy tissue. Conversely, for the ʻNo Tumorʼ class, the model's attention is more diffusely distributed across various brain structures, indicating that its prediction is based on the absence of localized anomalous features. This qualitative evidence strongly suggests that the model is not relying on spurious artifacts but has learned to identify genuine, clinically relevant biomarkers for each class. In contrast, the Grad-CAM visualizations of the lower-performing Swin-Tiny model are presented in Figure 5.

Visual interpretability of the Swin-Small model using Grad-CAM. The figure contrasts activation heatmaps for correctly classified examples (left panel) with those from misclassified examples (right panel) for Glioma, Meningioma, No Tumor, and Pituitary. Grad-CAM: Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping.

Visual interpretability of the Swin-Tiny, one of the lower-performing models, using Grad-CAM. The figure contrasts activation heatmaps for correctly classified examples (left panel) with those from misclassified examples (right panel) for Glioma, Meningioma, No Tumor, and Pituitary. Grad-CAM: Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping.

The Grad-CAM visualizations for the Swin-Small model, presented in Figure 4, demonstrate a remarkably high degree of alignment with clinical reality. For correctly classified instances of Glioma, Meningioma, and Pituitary tumors, the modelʼs attention is precisely localized on the neoplastic tissues, generating clean, high-intensity activation maps that are tightly constrained to the pathological regions of interest. This indicates that the model has successfully learned to identify genuine biomarkers and is not reliant on spurious or confounding artifacts in the surrounding anatomy. In the case of the ʻNo Tumorʼ class, the model exhibits a more diffuse attention pattern across various brain structures, which is an expected and logical outcome; its decision is correctly predicated on the absence of localized, anomalous features rather than the presence of a specific characteristic. This interpretability provides strong evidence that the Swin-Small architecture develops a nuanced and clinically relevant understanding of the input data.

In contrast, the activation heatmaps for the Swin-Tiny model, shown in Figure 5, expose the limitations of its reduced representational capacity. While the model often correctly classifies images, its attention is demonstrably less precise and more diffuse than its larger counterpart. For correctly classified tumor examples, the heatmaps frequently “bleed” into adjacent healthy tissue, and the focal intensity is scattered rather than concentrated. This suggests a more superficial level of feature extraction, where the model identifies the general vicinity of a tumor but struggles to delineate its precise boundaries. This deficiency becomes particularly apparent in its misclassified predictions. The visualizations show that the modelʼs attention is often misplaced on non-pathological structures or distributed nonsensically across the image, providing a clear visual rationale for its predictive errors. The modelʼs inability to consistently focus on clinically salient features corroborates its lower quantitative performance and suggests an incomplete or noisy learned representation of the target classes.

This study conducted a systematic comparison of Transformer-based architectures for brain tumor classification, yielding two principal findings. First, modern Transformer models exhibit outstanding diagnostic accuracy for this task, with all evaluated models surpassing 98.8% accuracy. Second, and more critically, our results demonstrate that maximal accuracy does not necessitate maximal model size. Architecturally efficient, mid-sized models like Swin-Small represent an optimal balance of high performance and computational feasibility, achieving peak accuracy of 99.37% while being nearly four times smaller and exhibiting more than twice the inference speed of the equally accurate Swin-Large model.

The superior performance-to-cost ratio of the Swin Transformer family, particularly Swin-Small, can be attributed to its architectural innovations. Unlike ViT, which applies a computationally intensive global self-attention mechanism, the Swin Transformerʼs use of local attention within shifted windows creates a hierarchical feature representation. This approach is conceptually analogous to the feature pyramids in CNNs and appears particularly well-suited for medical imaging, where pathological features are often localized and hierarchically structured. This inherent inductive bias allows the model to capture both fine-grained local details and broader contextual information more efficiently than a standard ViT.

A crucial aspect of translating such models into clinical practice is overcoming the “black box” problem to foster trust among clinicians. The inclusion of Grad-CAM analysis provides this vital layer of interpretability. Our visualizations confirm that the Swin-Small modelʼs predictions are based on clinically relevant regions, with attention maps precisely corresponding to tumor locations (Figure 4). By demonstrating that the modelʼs reasoning aligns with that of a human radiologist, we increase confidence in its diagnostic capabilities. This explainability is essential for any application where the model serves as a decision support tool, helping to guide a clinicianʼs attention or provide a rapid, verifiable second opinion.

The implications of these findings are significant for the practical deployment of AI-driven diagnostic systems, especially in resource-constrained scenarios. The high computational requirements and the confirmed increase in inference latency, as detailed in Table 2, associated with large models like ViT-Large or Swin-Large can be a prohibitive barrier, requiring specialized and expensive hardware not always available in clinical settings. In contrast, the efficiency of Swin-Small makes it a viable candidate for integration into existing clinical workflows and picture archiving and communication system (PACS) software, with the potential to run on standard hospital servers. This computational frugality democratizes access to state-of-the-art diagnostic tools, extending their benefits beyond large, well-resourced research centers and addressing a key challenge for real-world clinical applicability.

This study provides important information about the use of state-of-the-art Transformer architectures for brain tumor MRI classification through a comparative analysis of the models' performance and efficiency. Despite the findings validating the high potential diagnostic accuracy of all reviewed models, the analysis provides a richer finding: the highest performance does not always require the largest model. This research shows that moderately-sized architectures can achieve comparable success, with better efficiency, particularly the Swin-Small, compared to their larger alternatives, which can be computationally expensive. This finding is incredibly important when considering hardware and financial limitations of integrating AI-based diagnostic systems into clinical practice. The study implies that through the Swin Transformerʼs hierarchical design and DeiT modelʼs efficient training procedures, the architectural design can be more important than the actual size of the model. Therefore, this study provides a strong argument for a shift in thinking about medical imaging with deep learning systems away from increasing model size and towards better architectural design and computational efficiency. This shift enables the development of more practical and sustainable solutions, facilitating the integration of future diagnostic AI tools into clinical workflows.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that provide clear avenues for future research. First, our analysis was conducted on a single, albeit well-curated, public dataset. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of our findings, future work must validate these models on external, multi-institutional datasets. This would test their performance against variations in scanner hardware, imaging protocols, and patient demographics, which is a critical step for clinical translation.

Second, the present study was constrained to the analysis of 2D image slices. While computationally efficient, this approach does not fully exploit the rich, three-dimensional contextual information inherent in volumetric MRI data. A transition from 2D pixels to 3D voxels, however, presents a significant computational challenge. Such a shift would lead to a cubic increase in data input per patient, substantially elevating the memory and processing burden. Future work should therefore focus on extending these Transformer-based architectures to 3D, which may require novel model adaptations or training strategies to manage the increased computational complexity while potentially improving diagnostic accuracy by providing a more comprehensive understanding of tumor morphology.

Finally, future research should explore two additional dimensions to enhance diagnostic capabilities. One promising direction is multi-modal data fusion, which involves integrating other imaging sequences (e.g., T2-weighted, FLAIR) or non-imaging clinical data alongside the T1-weighted MRIs to provide complementary information and enhance predictive power. Another avenue is the advancement of model explainability. While Grad-CAM offers valuable insights, employing more advanced explainability (XAI) techniques could further demystify the models' decision-making processes, fostering greater clinical trust and accelerating the responsible integration of these powerful tools into routine neuroradiology workflows.

CNNs: convolutional neural networks

DeiT: Data-efficient Image Transformer

FN: false negatives

FP: false positives

GFLOPs: giga floating-point operations per second

Grad-CAM: Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

Swin: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows

TN: true negatives

TP: true positives

ViT: Vision Transformer

During the preparation of this work, the authors utilized artificial intelligence (AI) tools and large language models (LLMs) solely for the purpose of improving language and readability (e.g., grammar, spelling, and phrasing corrections). These tools were not used to generate, create, or alter the scientific content, data analysis, figures, or the core conclusions presented in this paper. All scientific content and intellectual contributions are entirely the work of the authors. The authors gratefully acknowledge the scientific support from the Health Institutes of Türkiye (TÜSEB). The Health Institutes of Türkiye (TÜSEB) provided the necessary artificial intelligence (AI) infrastructure and laboratory resources, which were essential for conducting the computational experiments and data analysis for this study. The computational resources for this research, including the high-performance computing units, were provided by the Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Application and Research Center at Igdir University.

YC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft. IP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Both authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

This study utilized a publicly available and anonymized dataset obtained from the Kaggle platform [38]. Therefore, institutional ethical approval was not required for this research.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The dataset used in this study is publicly available on Kaggle at [38].

Financial support is received from the Health Institutes of Türkiye (TÜSEB) under the “2023-C1-YZ” call, project number [33934]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.