Affiliation:

1Department of Internal Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena (–2023), 41100 Modena, Italy

Email: a.lonardo@libero.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-0698

Affiliation:

2Institute of Molecular Pathobiochemistry, Experimental Gene Therapy and Clinical Chemistry (IFMPEGKC), RWTH University Hospital Aachen, D-52074 Aachen, Germany

Email: rweiskirchen@ukaachen.de

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3888-0931

Explor Med. 2025;6:1001378 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2025.1001378

Received: October 01, 2025 Accepted: December 04, 2025 Published: December 17, 2025

Academic Editor: Alessandro Granito, University of Bologna, Italy

The management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) has evolved significantly, transitioning from a lack of therapeutic options to resmetiroma and semaglutide being licensed for use in MASH. With this evolving backdrop, this perspective article aims to explore the biological and clinical activities of tirzepatide, denifanstat, semaglutide, dapagliflozin, and efruxifermin, for which robust evidence of activity has been published. Tirzepatide and semaglutide, both GLP-1 receptor agonists, have shown significant efficacy in weight loss and metabolic improvements, while dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, offers renal protection alongside metabolic benefits. Denifanstat represents a novel approach targeting inflammation in MASH, potentially addressing the underlying pathophysiology. Efruxifermin is emerging as an innovative agent with dual mechanisms aimed at liver health and metabolic regulation. As we navigate this landscape of therapeutic options, we will discuss the implications for clinical practice and the necessity for personalized treatment strategies in managing MASH effectively. The rapid development of these therapies prompts critical evaluation—are we moving towards optimal treatment paradigms or encountering the challenge of over-treatment? This article seeks to provide insights into these evolving dynamics in MASH management.

Described as a clinical-histopathological definition in 1980, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [1], now renamed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [2], has remained a neglected area for drug development for decades. Beyond hepatology, MASH is a systemic condition involving liver-related issues (such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation), metabolic complications (like type 2 diabetes), and extrahepatic consequences (including cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and extrahepatic cancers) [3–8]. Furthermore, MASH has a high global prevalence [9, 10]. The systemic nature and widespread prevalence of MASH have led to significant economic burdens, with costs reaching $222.6 billion in the USA in 2017 and up to €19.5 billion in Europe, encompassing both direct (medical care, diagnostic procedures, drugs, hospitalization) and indirect costs (loss of productivity, reduced quality of life, morbidity, and mortality) [11, 12].

In 2024, resmetirom became the first drug licensed for use in the USA and was subsequently approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA) for the same indication in Europe in August 2025. These regulatory bodies made their decisions based on published evidence showing the superiority of both the 80 mg and 100 mg doses of resmetirom over placebo in resolving NASH and improving liver fibrosis by at least one stage [13]. In August 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also approved semaglutide for the treatment of MASH with moderate or advanced fibrosis [14] based on the results of a published trial [15].

In addition to resmetirom and semaglutide, other drugs are currently being evaluated in the field of MASH, as shown in Table 1. Drugs such as tirzepatide [16], denifanstat [17], dapagliflozin [18], and efruxifermin [19] have demonstrated efficacy in placebo-controlled double-blind, randomized clinical trials. What is common among these drugs? Table 2 highlights the significant diversity in chemical structures and mechanisms of action among these drugs, with resmetirom being the only agent approved for use in MASH in both the USA and Europe, alongside other promising drugs that have shown potential benefits in improving liver histology outcomes.

Recent randomized controlled clinical trials with new drugs in the MASH arena.

| Drug | Method | Findings | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide | A Phase 2 dose-finding, multicenter, double-blind RCT with 157 participants who had biopsy-proven MASH and stage F2 or F3 fibrosis. They were randomly assigned to receive either ow sc tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg) or a placebo for 52 weeks. | The proportion of participants who met the criteria for resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis was 10% in the placebo group, 44% in the 5 mg tirzepatide group (∆ vs. placebo, 34% points; 95% CI, 17 to 50), 56% in the 10 mg tirzepatide group (∆ 46% points; 95% CI, 29 to 62), and 62% in the 15 mg tirzepatide group (∆ 53% points; 95% CI, 37 to 69) (p < 0.001 for all three comparisons).The proportion of participants who exhibited improvement of ≥ 1 fibrosis stage without worsening of MASH was 30% in the placebo group, 55% in the 5 mg tirzepatide group (∆ vs. placebo, 25% points; 95% CI, 5 to 46), 51% in the 10 mg tirzepatide group (∆, 22% points; 95% CI, 1 to 42), and 51% in the 15 mg tirzepatide group (∆, 21% points; 95% CI, 1 to 42). The most common adverse events in the tirzepatide groups were mostly mild or moderate GI events. | Tirzepatide administration for 52 weeks to participants with MASH and moderate or severe fibrosis was more effective than placebo in inducing MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis. | Loomba et al., 2024 [16] |

| Denifanstat | A Phase 2b multi-center, double-blind RCT including 168 participants who were randomized to receive either 50 mg denifanstat od (n = 112) or placebo (n = 56). | 38% of participants in the denifanstat group had a ≥ 2-point improvement in NAS without worsening of fibrosis versus nine (16%) of 56 participants in the placebo group (p = 0.0035). 26% of participants in the denifanstat group showed MASH resolution with a ≥ 2-point improved NAS without fibrosis worsening vs. 11% of participants in the placebo group (p = 0.0173). The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were COVID-19 (17% of those receiving denifanstat vs. 11% in the placebo group), ocular dryness, and hair loss. | Denifanstat induced a significant improvement in NAS, MASH resolution, and fibrosis. | Loomba et al., 2024 [17] |

| Semaglutide | Ongoing Phase 3 multicenter, double-blind RCT involving 1,197 subjects with biopsy-proven MASH and stage 2–3 fibrosis. They were assigned to receive either ow sc 2.4 mg semaglutide or a placebo for 240 weeks. | MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis was observed in 62.9% of those receiving semaglutide vs. 34.3% of those in the placebo group (p < 0.001). Reduced liver fibrosis without MASH worsening was found in 36.8% of those assigned to semaglutide vs. 22.4% of those receiving placebo (p < 0.001). | Ow 2.4 mg semaglutide improved liver histology findings at week 72 among individuals with MASH and moderate or advanced liver fibrosis. | Sanyal et al., 2025 [15] |

| Dapagliflozin | 54 adults with biopsy-proven MASH, with or without T2D, were randomly assigned to receive 10 mg of dapagliflozin orally or a matching placebo od for 48 weeks. | MASH improvement without worsening of fibrosis was reported in 53% of those assigned to dapagliflozin vs. 30% receiving placebo (p = 0.006). The mean difference in NAS was also significant (p < 0.001). MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis occurred in 23% of participants receiving dapagliflozin vs. 8% in the placebo group (p = 0.01). Fibrosis improvement without worsening of MASH was reported in 45% of participants treated with dapagliflozin vs. 20% of those receiving placebo (p = 0.001). The proportion of those who had adverse events leading to discontinued treatment was 1% with dapagliflozin vs. 3% with placebo. | Compared to placebo, dapagliflozin administration for 48 weeks led to a higher percentage of individuals with MASH improvement without worsening fibrosis, as well as MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis and fibrosis improvement without worsening of MASH. | Lin et al., 2025 [18] |

| Efruxifermin | Phase 2b multicenter, double-blind, RCT including 126 participants who were assigned to receive sc efruxifermin (28 or 50 mg) once per week or a placebo. | Of 88 participants with week-96 biopsies, ≥ 1-stage fibrosis improvement without MASH worsening was observed in 24% of 34 participants randomized to the placebo group, 46% of those receiving 28 mg (p = 0.070), and 75% of those in the 50 mg group (p < 0.0001). Mild-to-moderate GI adverse events were more common with efruxifermin than with placebo. | After 96 weeks, treatment with efruxifermin resulted in greater improvements in fibrosis than placebo. | Noureddin et al., 2025 [19] |

CI: confidence interval; ∆: difference; GI: gastrointestinal; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; NAS: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score; od: once daily; ow: once-weekly; RCT: randomized, placebo-controlled trial; sc: subcutaneous; T2D: type 2 diabetes.

Heterogeneity of drugs in MASH treatment.

| Drug name and chemical structure | Drug class | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

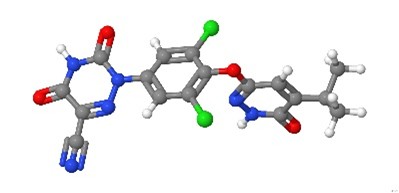

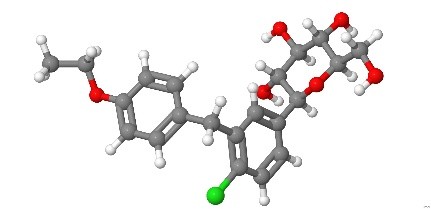

Resmetirom Resmetirom | Liver-selective THR agonist | Counteracts intrahepatic hypothyroidism in MASH by reducing LFC, liver enzymes, hepatic fibrogenesis, and LDL-Chol. | Lonardo, 2024 [20] |

Semaglutide Semaglutide | GLP-1 RA | Reduces IR by lowering total body weight and visceral adiposity, blood pressure, CRP levels, and improving lipid profiles. | Weiskirchen and Lonardo, 2025 [21] |

Tirzepatide Tirzepatide | Dual GIP/GLP-1 RA | Improves glycemic homeostasis and promotes weight loss. | Lonardo and Weiskirchen, 2025 [22] |

Denifanstat Denifanstat | FASN inhibitor | Blocks DNL, a key step in MASH pathogenesis. | Loomba et al., 2024 [17] |

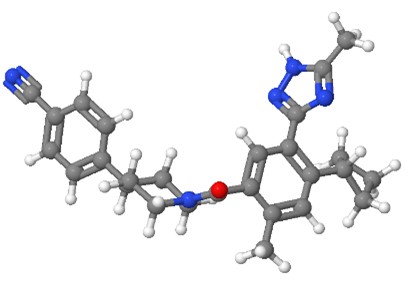

Dapagliflozin Dapagliflozin | SGLT2 inhibitor | Modulates energy homeostasis, reduces IR, and exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-fibrotic effects. | Lin et al., 2025 [18] |

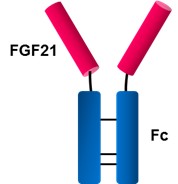

Efruxifermin Efruxifermin | FGF21 analogue | Exerts antifibrotic activity, reduces liver steatosis, IR, and dyslipidemia. | Harrison et al., 2024 [23] |

CRP: C-reactive protein; DNL: de novo lipogenesis; FASN: fatty acid synthase; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; GIP: gastrointestinal peptide; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; IR: insulin resistance; LDL-Chol: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LFC: liver fat content; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; RA: receptor agonist; SGLT2: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; THR: thyroid hormone.

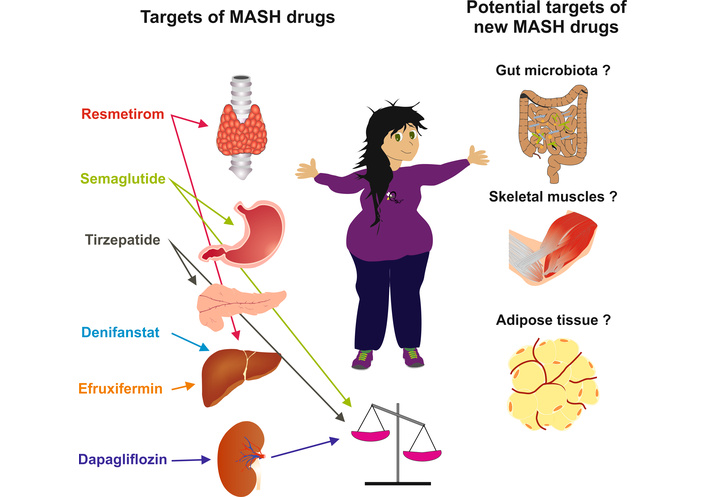

Taken collectively, recent studies summarized in Table 1, along with the heterogeneous mechanisms of action of these drugs illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 1, clearly document the notion that the pathogenesis of MASH involves both hepatic.

Targets and potential targets of MASH drugs. Graphical illustration of the variety of organ targets underlying the various mechanisms of action of resmetirom, semaglutide, tirzepatide, denifanstat, efruxifermin, and dapagliflozin. Major determinants of MASH pathogenesis, including gut microbiota, skeletal muscle, and visceral adipose tissue, are potential targets of innovative drugs in this field. MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

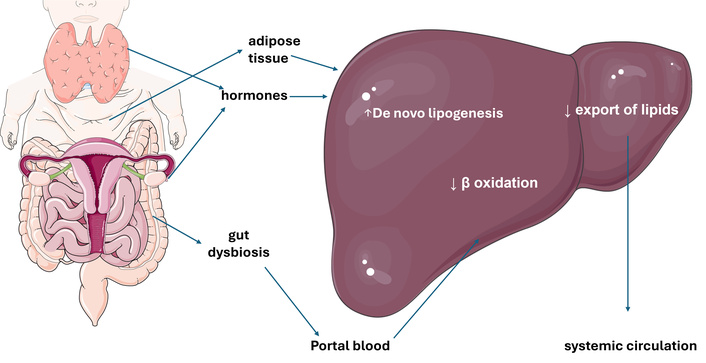

Additionally, MASH pathomechanisms exhibit substantial inter-individual variability [24, 25], paving the way for precision medicine approaches aiming to offer the right drug to the right person at the right moment (Figure 2) [26, 27].

Principal pathomechanisms involved in MASLD. Schematic representation of extrahepatic and hepatic determinants of MASLD. Increased lipogenesis from expanded and inflamed adipose tissue results in an overflow of fatty acids inundating the liver. This increased substrate supply, along with reduced β oxidation of triglycerides and decreased capacity to export lipids into the bloodstream, leads to increased lipogenesis, facilitated by insulin resistance. Concurrently, gut dysbiosis induces a leaky gut condition, allowing bacterial antigens to enter the portal system, contributing to maintaining a proinflammatory state within the hepatic tissue. Finally, various gene variants and hormonal changes facilitate the development and progression of MASLD. MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. The original illustration, based on current pathogenic views [3], was created using Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com) and licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The lesson from MASH drug trials is that there seem to be numerous different therapeutic targets. This concept opens the door to investigating other yet unexplored pathways involved in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) development. Future research should be developed along different trajectories. First, we need to identify and validate robust disease biomarkers that characterize distinct and homogeneous patient populations. MASH drugs should be utilized based on patient-specific pathogenesis. For example, patients need to be characterized along macro domains such as sex. Data indicating that sex may influence MASH continue to accumulate [28], and these sex discrepancies lay the foundation for sex- and reproductive-status specific analysis of trials [29, 30]. Moreover, specific gene variants may also require distinct drug approaches [31–33]. Additionally, it will be important to study in increasing detail how novel MASH drugs impact not only the molecular pathways involved but also the cellular bases of MASH [34]. Finally, while available drugs address certain molecular targets and pathways, innovative MASH drugs modifying different pathways and targets remain to be investigated (Figure 1).

These comprise the prospect of MASH treatment regarding i) the gut microbiota, ii) skeletal muscle, and iii) visceral adipose tissue.

The gut-liver axis plays a key role in MASLD, with reduced alpha diversity and certain microbial profiles being associated with worse outcomes [35]. Microbiome-targeted therapies, such as fecal microbiota transplantation, antibiotics, bile acid modulators, and probiotics, demonstrate potential in combating intestinal dysbiosis, reducing bacterial populations responsible for endotoxin production, decreasing gut barrier permeability, restoring normal bile acid metabolism, improving liver chemistries, and eventually mitigating disease progression [36]. However, further research is required to elucidate their mechanisms of action and optimize therapeutic efficacy.

Currently, there are no approved medications for sarcopenia. In addition to lifestyle changes (i.e., diet and exercise) that may help reverse sarcopenia and lower insulin resistance, several investigational drugs target skeletal muscle to improve metabolic and physical function [37, 38].

Testosterone supplementation and vitamin D replacement, unless otherwise contraindicated, may be considered in individuals with documented deficiencies [38]. Investigational approaches against sarcopenia with beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, bimagrumab, myostatin inhibition alongside glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) therapy, and BIO101 are detailed elsewhere [38].

The pathomechanisms of obesity-associated MASLD include lipotoxicity, inflammation, fibrogenesis, and carcinogenic risk [39], suggesting that combating obesity is a major objective in treating MASLD. Various strategies are available to this end. These comprise lifestyle changes, which are hard to sustain over the long term, various drugs including semaglutide and terzepatide, endoscopic techniques, and bariatric surgery [21, 22, 39–41].

Collaboration among clinicians, researchers, and public health authorities is essential to create an effective precision medicine strategy for tackling global obesity-related chronic liver disease (CLD) [39].

The abundance of different drug options in the MASH arena, rather than a limitation, potentially offers additional advantages in the context of combination therapy. Drugs with different mechanisms of action may be rationally utilized with the aim of reducing doses and side effects of each drug class while maximizing the therapeutic benefit [42]. In this regard, areas in need of further investigation include the combined utilization of GLP-1 RA with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) analogues or antifibrotic agents [43]. Additionally, although the regulatory approval of combination therapy remains challenging [43], the association of currently available drugs that restore normal metabolic function (e.g., traditional antidiabetic, lipid-lowering drugs, anti-hypertensives, and antioxidants), with MASH-specific drugs represents an arena of potentially great significance. Approaches addressing the specific pathomechanisms involved in the individual patient promise to correct the underlying driving force of MASH [44].

A final consideration regards the financial and ethical sustainability of increasingly expensive drug approaches that some areas of the world have to utilize to combat the deleterious effects of unhealthy lifestyle habits on liver health [21, 45, 46], while other countries still struggle against famine and intermittent access to food [47].

The landscape of drug treatment for MASH is rapidly evolving, with two licensed drugs, resmetirom and semaglutide, and a growing array of additional therapeutic options demonstrating promising efficacy. The diverse mechanisms of action among agents such as tirzepatide, denifanstat, semaglutide, dapagliflozin, and efruxifermin highlight the complexity of MASH pathogenesis and the need for tailored treatment approaches. As we advance our understanding of these therapies and their clinical implications, it is crucial to balance the potential benefits with the risks of over-treatment. Ideally, all stakeholders should be involved in future studies, namely, investigators, patients, regulatory agencies, and industry [48]. Future research should focus on identifying patient-specific biomarkers, measuring portal pressure when clinically indicated, and optimizing combination therapies to enhance outcomes while minimizing adverse effects. Ultimately, a precision medicine approach will be essential in navigating this multifaceted condition and improving patient care in MASH management.

GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

The authors thank Sabine Weiskirchen (IFMPEGKC) for her help in drawing the figures for this manuscript.

AL and RW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Amedeo Lonardo, who is the Associate Editor of Exploration of Medicine, and Ralf Weiskirchen, who is the Editorial Board Member of Exploration of Medicine, both had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1821

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0