Affiliation:

Department of Biomedical Engineering, Meybod University, Meybod 8961699557, Iran

Email: Kh.rezaee@meybod.ac.ir

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6763-6626

Affiliation:

Department of Biomedical Engineering, Meybod University, Meybod 8961699557, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-5958-4121

Affiliation:

Department of Biomedical Engineering, Meybod University, Meybod 8961699557, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9575-4313

Explor Med. 2025;6:1001376 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2025.1001376

Received: August 01, 2025 Accepted: October 30, 2025 Published: December 04, 2025

Academic Editor: Shannon L. Risacher, Indiana University School of Medicine, USA

Aim: Early screening for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) using facial images is promising but often limited by small datasets and the lack of deployable models for resource-constrained settings. To develop and evaluate a lightweight framework that combines a multi-scale vision transformer (MS-ViT) with edge optimization for ASD classification from children’s facial images.

Methods: We analyzed 2,940 RGB facial images of children obtained from a publicly available Kaggle dataset. Faces were detected, aligned, and cropped (ROI extraction), then normalized; training used standard augmentations. The backbone was an MS-ViT with multi-scale feature aggregation. We performed an 80/20 stratified split (training/testing) and used five-fold cross-validation within the training set for validation (i.e., ~64% training, ~16% validation, and 20% testing per fold). Edge deployment was enabled through post-training optimization. Performance was assessed using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC-ROC, and per-image inference time.

Results: The best configuration (MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented) achieved an accuracy of 96.85%, sensitivity of 96.09%, specificity of 97.92%, and AUC-ROC of 0.9874. On a Raspberry Pi-class device, the model reached ~181 milliseconds per image, supporting real-time screening.

Conclusions: The proposed “MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented” framework offers near-state-of-the-art accuracy with low latency on low-power hardware, making it a practical candidate for early ASD screening in clinics and schools. Limitations include dataset size and demographic diversity; prospective clinical validation on larger, multi-site cohorts is warranted.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent difficulties in social interaction, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and challenges in both verbal and nonverbal communication [1]. While genetic abnormalities during fetal brain development are primary contributors, environmental factors may exacerbate the condition [2]. Early symptoms—such as avoiding eye contact, failing to respond to one’s name, and reduced social engagement—are often subtle, which complicates timely diagnosis for both parents and clinicians [3, 4]. Longitudinal evidence indicates that infants later diagnosed with ASD can exhibit atypical brain development and distinctive behavioral patterns (e.g., differences in motor skills, sensory processing, and emotional regulation) as early as the first year of life [5]. These observations underscore the value of early detection: leveraging heightened neuroplasticity in early childhood can improve cognitive and language outcomes through targeted interventions [6].

Epidemiologically, ASD represents a substantial public-health concern. Recent surveillance by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports high prevalence among school-age children, with marked sex differences (higher in boys than girls), highlighting the need for accessible screening pathways and family support structures. Early diagnosis improves developmental outcomes and assists families in planning structured support programs [7, 8].

Conventional diagnostic pathways—predominantly questionnaire-based tools administered by trained specialists—remain the clinical gold standard but are time-consuming, costly, and dependent on expert availability [9, 10]. To mitigate these limitations, research has explored more objective modalities, including neuroimaging and physiological monitoring. Magnetic resonance imaging and brain-signal analyses reveal structural and functional differences associated with ASD [11], while physiological signals (e.g., skin conductance and heart-rate variability) help characterize affective and stress responses [12]. However, these approaches require advanced equipment and specialized expertise, limiting their scalability in routine practice [13]. This has motivated the development of innovative, data-driven tools leveraging machine learning (ML) [14].

ML methods can process large datasets and uncover subtle, diagnostic patterns. In particular, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) applied to static facial images and eye-tracking signals have achieved high precision in identifying ASD-related cues, while remaining non-invasive and inherently scalable [15, 16]. Within this trajectory, facial image analysis has emerged as a promising direction for early ASD screening. By examining craniofacial characteristics—such as eye shape, cheekbone length, and nose dimensions—facial analysis supports both early detection and longitudinal monitoring; multiple studies have reported distinctive craniofacial morphology in ASD compared with neurotypical peers [1, 3, 17]. Typical pipelines employ high-resolution facial images with preprocessing (resizing, normalization, noise reduction) to ensure data quality and robustness [18]. Feature extraction often emphasizes geometric/structural cues to capture ASD-associated craniofacial differences, and downstream classifiers range from tree-based models to deep CNNs.

Representative studies illustrate the landscape: transfer-learning on Kaggle-sourced facial images shows effective early-sign detection in young children [19]; other reports have adapted lightweight CNNs (e.g., MobileNet) for ASD classification with strong accuracy/recall [3]; decision-tree pipelines using ~2,936 facial images and automated tooling (e.g., Hyperpot) reached ~96% accuracy [20]. Beyond static images, face-based real-time assessment has been explored to quantify attentional states using support vector machines (SVMs)/CNNs [21], and static facial analysis has been extended into educational settings (e.g., AlexNet-based rapid screening) with emphasis on cost-effectiveness [22]. More recent deep learning frameworks integrate multiple pretrained backbones (VGG16/19, InceptionV3, VGGFace, MobileNet) with augmentation and explainability tools (e.g., LIME), reporting up to ~98% accuracy while improving interpretability [23]. Hybrid attention-based models combining ResNet101 and EfficientNetB3 leverage self-attention to capture subtle cues with ~96.5% accuracy, though computational demands may hinder low-resource deployment [24]. Broader evaluations that couple DenseNet/VGG/ResNet/EfficientNet with vision transformer (ViT) suggest complementary strengths of convolutional and attention-based representations (e.g., 89% with ResNet152, improving to ~91% when fused with ViT) [25]. Optimization of lightweight backbones (e.g., MobileNetV2 via refined gravitational search) has also achieved strong results (~98% accuracy; ~97.8% F1-score), positioning such models for mobile/real-time scenarios—albeit with potential sensitivity to uncontrolled imaging conditions [26]. Multi-modal and ensemble approaches show near-ceiling performance in some settings [e.g., artificial neural network (ANN)-based tabular + image boosting with high accuracy], but their complexity may challenge real-world integration [27]. ViT-based pipelines with attention mechanisms (e.g., Squeeze-and-Excitation) demonstrate promising discrimination using static facial features, offering a scalable biomarker for early screening while requiring careful curation and substantial training resources [28]. Geometry-aware methods that incorporate roll-pitch-yaw (RPY) and curvature/landmark cues can classify ASD presence and even severity [29], though reliance on precise orientation and complex geometry may limit usability in unconstrained environments.

We address a supervised, image-based screening task: given a single red-green-blue (RGB) facial image of a child, the model outputs the probability of ASD (binary classification: ASD vs. neurotypical). The intended use is preclinical screening—not definitive diagnosis—in settings where specialist access and computing are limited. We use a publicly available Kaggle repository of ~3,000 children’s facial images with ASD/neurotypical labels curated by the dataset providers. The dataset’s size and demographic balance are limited; detailed characteristics, licensing terms, and the splitting strategy are reported in Materials and methods. Facial regions of interest (ROI; eyes-nose-mouth) are detected, aligned, and cropped; pixel intensities are normalized; and training-time augmentation addresses pose/illumination variability. Rather than hand-crafted geometry, we learn multi-scale facial representations using a multi-scale ViT (MS-ViT), which aggregates features across resolutions before classification.

Moreover, we perform an 80/20 stratified split (training/testing) with five-fold cross-validation within the training portion for validation/model selection, ensuring subject-level separation to prevent identity leakage. We report accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC)-receiver operating characteristic (ROC), and we measure per-image inference time on Raspberry Pi-class hardware [~181 milliseconds (ms)/image] to establish deployability. Thus, the principal contributions of this study are as follows: (1) a deployable image-based screening framework that combines ROI-centric preprocessing, multi-scale transformer features, and edge optimization; (2) a thorough evaluation including ablations and on-device latency, emphasizing the accuracy-efficiency trade-off critical for real-world use; (3) a transparent protocol (stratified split, cross-validation, subject-level separation) that supports reproducibility and fair comparison.

Despite encouraging progress, prior work faces recurring limitations: small or demographically homogeneous datasets, limited generalizability across populations and imaging conditions, and computational complexity that impedes on-device or low-resource deployment. Some high-performing models depend on multi-modal inputs or intricate architectures, complicating clinical scalability and maintenance. In response to these gaps, this study proposes a lightweight, real-time-capable framework that combines robust preprocessing and explainable components with modern deep architectures, aiming to balance diagnostic accuracy with interpretability and deployability in clinical and resource-constrained settings. Specifically, we (1) analyze and benchmark image-based screening using accuracy as the primary criterion (with computational complexity and clinical applicability as secondary criteria) [17], (2) identify shortcomings in current datasets and reporting practices, and (3) present a practical framework that maintains strong performance while improving feasibility for real-world use.

Section Materials and methods describes the materials and methods, including preprocessing steps, architectural components, and optimization strategies. Section Results presents the experimental setup, dataset details, and performance results. Section Discussion discusses the findings relative to prior studies, highlighting strengths and limitations of the proposed model. Section Conclusion concludes and outlines directions for future research.

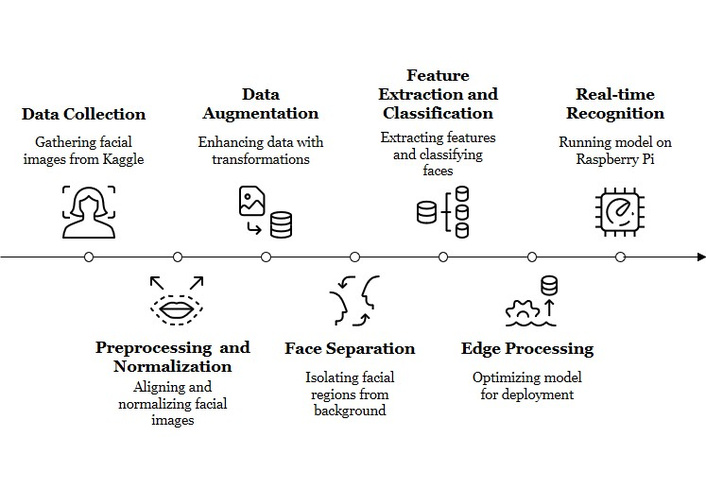

The goal of this work is an automated binary ASD screening task: given a single RGB facial image of a child, the system estimates the likelihood that the child belongs to the ASD group versus the non-ASD (neurotypical) group. The method is intended as an assistive early screening tool, not as a stand-alone clinical diagnosis. Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed pipeline.

Overview of the proposed ROI-centric, multi-scale ViT pipeline for ASD screening—covering face ROI preprocessing and normalization, train-only augmentation, multi-scale transformer feature extraction, and edge optimization for on-device inference. Original illustration created by the authors; no third-party material used. ROI: regions of interest; ViT: vision transformer; ASD: autism spectrum disorder.

The pipeline consists of three main stages:

1) Face ROI extraction and preprocessing: We first detect and crop a normalized facial ROI for each child image. This step is designed to emphasize craniofacial structure (e.g., relative geometry of the eyes, nose, and mouth) while removing background clutter and illumination artifacts. The full preprocessing procedure, including ROI extraction and data augmentation, is described in Section Preprocessing and data augmentation.

2) MS-ViT classifier: The cropped face ROI is then processed by our MS-ViT. In this work, “MS-ViT” refers to a ViT backbone that extracts features at multiple spatial scales in parallel and fuses them, so that both global craniofacial proportions and fine local cues (such as periocular shape or mouth region detail) are modeled jointly. The MS-ViT architecture, fusion mechanism, and classification head are described in Section Model.

3) Edge artificial intelligence (AI) optimization/on-device deployment: After training, we apply an edge optimization stage that performs post-training quantization (PTQ) (INT8) and structured pruning to reduce the model’s memory footprint and inference latency. This “Edge AI Optimizer” stage enables the model to run on resource-constrained hardware (e.g., embedded boards) with sub-second latency per image while keeping the data local on the device. The deployment flow and latency measurements are reported in Section Edge computing.

This modular design directly addresses practical constraints such as compute cost, privacy, and responsiveness. Local (on-device) inference reduces the need to upload children’s facial images to the cloud, which is desirable from an ethical and privacy standpoint. In addition, each block in Figure 1 corresponds to an ablation factor we evaluate later (ROI cropping, augmentation, multi-scale fusion, and edge quantization/pruning), allowing us to quantify the contribution of each component to accuracy and latency.

The dataset used in this study consists of 2,940 facial images of children, collected from a publicly available Kaggle repository [30]. This corpus contains facial photographs of children with and without autism and is distributed for research use under the terms defined on its Kaggle page; we used the data accordingly and did not collect new images. The supervised task is binary screening (ASD vs. neurotypical) from a single RGB facial image. Sample images from this dataset, including both neurotypical and ASD-labeled cases, are illustrated in Figure 2 to provide visual context for the model’s input data. Class labels are provided by the dataset curators; no independent clinical re-verification was performed by the authors. This dataset is not a prospectively collected clinical cohort; labels typically come from the original public sources (e.g., caregiver/self-report) and therefore should be interpreted as screening-level, not as a confirmed medical diagnosis.

Several examples of images of healthy (neurotypical) children and those with autism spectrum disorder [30]. Images are shown solely to illustrate input characteristics; identities are not disclosed, and presentation follows journal policies.

Prior studies using this Kaggle dataset report children approximately 2–14 years old (most cases in the 2–8 range), with images predominantly from Europe and the United States; therefore, the dataset is not demographically representative of global populations [31–33]. Exact age is not available for every child, and race/ethnicity metadata is generally missing, so age-stratified or fairness-by-ethnicity analysis is not possible.

Published reports note that many images were downloaded from autism-related websites and Facebook pages; labels are provided as binary ASD vs. non-ASD by the dataset curators [32]. We did not assign or modify these labels, and we did not collect any new images. In line with prior reports, the corpus comprises ~2,936 2D RGB images, and studies describe a near 1:1 class balance (autistic vs. non-autistic) [31, 32]. All images are standard RGB photographs; no infrared, depth, or multispectral imaging is available. The “multi-scale” term later in the paper refers to multi-scale feature extraction in the model, not to multispectral sensors. Because images originate from heterogeneous public web sources, the dataset exhibits uncontrolled pose, illumination, background clutter, occlusions/accessories (e.g., glasses, hats), and expression differences. This variability motivates our ROI-centric preprocessing, augmentation policy, and multi-scale modeling [32].

We performed an 80/20 stratified split (training/testing), preserving the ASD:non-ASD ratio and retaining an independent hold-out test set. Within the 80% training portion, we used five-fold cross-validation for validation/model selection (~64% train, ~16% validation, 20% test per fold). To prevent identity leakage, splits were performed at the subject level wherever multiple images per child were present. Augmentations were applied to training folds only; validation/test were never augmented.

We used a public, de-identified dataset and did not collect new data. For deployment, we advocate on-device inference, minimal data retention, and optional de-identification (e.g., landmark-only or blur-based strategies) to mitigate re-identification risks. Any eventual clinical or school use would require explicit guardian consent and formal approval by medical/ethical boards; this work does not claim clinical certification.

Prior work has shown that both facial data and other medical imaging data can expose sensitive identity information, and that de-identification strategies are needed to suppress identifiable cues while preserving clinically relevant content [34–37]. Our focus on local/on-device inference and ROI-level processing is aligned with this direction, because it avoids unnecessary external transmission and storage of full-face images.

Notably, the dataset used in this work consists of publicly available facial images of children that have been released for research use under the terms specified by the source repository. All analyses in this study were conducted on that existing dataset; no new images were collected. Because facial images of minors are highly sensitive, our framework is explicitly designed to minimize external exposure of the data: Inference is performed locally on the device after edge optimization, without uploading images to external servers. The model operates only on the cropped facial ROI, and we consider optional de-identification strategies such as facial landmark-based representations or controlled blurring for future deployment scenarios. We also note that any real-world screening application would require appropriate parental/guardian permission, explicit communication of purpose and data handling, and compliance with institutional and regulatory standards for working with minors.

The data preparation process consists of three key steps: normalization, data augmentation, and ROI extraction. These steps enhance both the quality and diversity of the input data, contributing to improved model accuracy and efficiency. For each image, we first detect and crop a consistent facial ROI that centers on the child’s face and excludes most of the background. The ROI is aligned to include key facial structures such as the eyes, nose, mouth, and overall facial contour. This improves robustness to clutter, pose changes, and lighting variation in the original, in-the-wild images, and ensures that the classifier focuses on the child’s face rather than unrelated context.

In this work, when we refer to “craniofacial features”, we mean the overall geometric relationships and proportions of visible facial regions (for example, relative eye spacing, facial width-to-height ratio, nose-mouth distance, and periocular shape). These patterns have been discussed in prior autism-related facial studies as potentially discriminative cues. Here, we do not hand-engineer explicit measurements; instead, we provide the normalized face ROI to the model so that the MS-ViT can learn such cues directly from the image.

Normalization, a fundamental preprocessing step, standardizes pixel values to a consistent range (typically between 0 and 1), ensuring uniformity and precision in analysis. This process mitigates variations caused by lighting, contrast, and image quality, thereby enhancing the model’s feature extraction capabilities.

Figure 3 illustrates various data augmentation techniques applied to children’s facial images, each designed to enhance the diversity and robustness of the training dataset. These transformations—including rotation, horizontal flipping, cropping, brightness enhancement, contrast adjustment, noise injection, and blurring—simulate real-world variability in image acquisition, such as differences in lighting, orientation, and facial pose. By exposing the model to such diverse visual patterns, these augmentations help mitigate overfitting and significantly improve the model’s ability to generalize across unseen data. Augmentations are applied only to the training split; validation and test images are not augmented.

Various data augmentation methods are applied to a facial image, including rotation, flipping, cropping, brightness and contrast adjustments, noise addition, and blurring. These steps improve dataset diversity and help the model generalize more effectively to real-world conditions.

Such preprocessing and augmentation steps are critical in real-time screening scenarios, where image quality and consistency cannot always be guaranteed. In the proposed MS-ViT and Edge AI hybrid framework, these techniques contribute directly to the accurate extraction of relevant facial cues associated with ASD risk from RGB images. By enriching the input space and stabilizing the facial ROI, the system becomes more resilient to pose, lighting, and occlusion. Any future use in clinical or educational settings would still require formal expert validation and appropriate ethical approval.

The core of the proposed framework is MS-ViT, a multi-scale vision transformer. In our design, the same cropped facial ROI—an aligned RGB face crop of the child—is processed in parallel at multiple spatial resolutions (“scales”). Each scale-specific branch produces its own feature representation, and these representations are fused through a learnable weighted combination:

Here, X is the cropped RGB facial ROI; MS-ViTi(X) is the feature map produced by the MS-ViT branch operating at spatial scale i; wi is a learnable scalar weight controlling the contribution of scale i; n is the number of spatial scales (i.e., the number of parallel branches); and Ffinal is the fused multi-scale feature representation used for classification. The weights wi are trained jointly with the rest of the network so that the model can automatically emphasize whichever spatial resolution is most informative. All inputs in this work are standard RGB face crops; no multispectral or infrared modalities are used.

To support low latency, on-device inference on resource-constrained hardware (e.g., Raspberry Pi-class devices), we apply a post-training edge optimization stage. This “edge optimization” step performs uniform quantization and structured channel pruning on the trained MS-ViT model. The goal is to reduce memory footprint and inference time without retraining the model from scratch or changing the task (binary ASD vs. neurotypical classification). Uniform b-bit linear quantization of a weight tensor W is defined as:

where Wq is the quantized integer tensor (values in [0, 2b – 1]), W is the original full-precision weight tensor, b is the bit width (e.g., b = 8 for INT8), and min(W) and max(W) are the minimum and maximum values of W.

We further apply structured channel pruning to remove low-importance channels and reduce multiply-accumulate cost. Pruning can be expressed as an element-wise masking operation:

where Wp is the pruned weight tensor, M is a binary mask of the same shape (1 = keep, 0 = prune), and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. We use structured (channel-level) pruning so that the resulting tensors remain efficient for integer execution on embedded CPUs. After pruning, the quantized/pruned model is exported in INT8 form and run locally on the device, avoiding the need to transmit children’s facial images to an external server.

All images in this work are standard RGB facial photographs of children. The term “multi-scale” refers to multiple spatial resolutions within the MS-ViT, not to multispectral sensing. After fusion, the final representation Ffinal is passed through fully connected layers for binary classification.

In the final decision-making phase, the extracted and fused features from multiple levels are processed through fully connected layers to perform the final classification. The supervised task is binary ASD screening: given a single face ROI (a child’s RGB facial image), the model outputs ASD vs. neurotypical. The learnable fusion weights allow the model to combine low-level cues (texture, local symmetry, contour sharpness) with higher-level craniofacial layout (relative positioning of eyes, nose, and mouth). This structure leverages multi-scale feature extraction as well as edge optimization to enable accurate predictions with low latency on resource-limited hardware.

This combination suggests technical feasibility for rapid, on-device ASD risk screening in settings such as schools or primary care clinics where computational resources and specialist access may be limited. Any real clinical or educational deployment, however, would require formal validation by medical experts, regulatory approval, and explicit guardian consent. Unlike a plain single-scale ViT, the proposed MS-ViT is co-designed with its edge optimization stage: it performs multi-scale facial feature fusion while also being compressible via quantization and pruning for local, privacy-preserving inference.

The system is trained for supervised binary classification (ASD vs. neurotypical) from a single 224 × 224 RGB face ROI. We optimize a standard binary cross-entropy loss with L2 regularization:

Here, yi ∈ {0, 1} is the ground-truth label for sample i (1 = ASD, 0 = neurotypical); pi is the predicted ASD probability for that sample; N is the minibatch size; θ denotes all trainable model parameters; and

Hyperparameters (learning rate, weight decay, batch size, regularization/dropout, and augmentation magnitudes) are tuned via a compact iterative search over reasonable ranges, guided by validation AUC-ROC and training stability. We report threshold-agnostic metrics (AUC-ROC) directly. For thresholded metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity), a single operating point τ* is fixed from validation by maximizing Youden’s J :

and the same τ* is used on the test set to avoid optimistic bias. All random seeds for splitting, augmentation, and optimization are fixed to support reproducibility. Calibration samples used later for PTQ are drawn exclusively from the training split and are described in the Edge-optimization subsection; the test set is never used for tuning, calibration, or threshold selection.

We performed a focused hyperparameter search to select the final training configuration. The parameters we tuned were the initial learning rate, weight decay, batch size, dropout strength, and augmentation strength (rotation, crop, brightness/contrast jitter). The learning rate was explored in the range 1 × 10–5 to 1 × 10–3; weight decay was varied between 1 × 10–6 and 1 × 10–3; batch size was varied between 16 and 64; and dropout probabilities were tested in the range 0.1–0.5. Data augmentation settings were varied within mild to moderate ranges, for example, in-plane rotation up to ± 15°, random cropping up to 10%, and brightness/contrast jitter up to ± 20%. For each candidate setting, we trained the model with the same supervised objective (binary cross-entropy with L2 regularization) and measured mean validation AUC-ROC across the five-fold cross-validation splits, using subject-level separation. Fewer than 30 unique configurations were evaluated. The best-performing configuration under this criterion was then retrained on the full 80% training portion and evaluated once on the held-out 20% test split, with the decision threshold τ* fixed from validation as described in Equation (5).

To support real-time screening on embedded hardware without altering the trained decision function, we add a post-training edge optimization stage consisting of 8-bit quantization (INT8) and structured channel pruning. This stage is applied after full-precision training; validation and test partitions remain untouched and subject-level separation is preserved. The goal is to reduce latency, memory, and compute while keeping the model’s behavior aligned with the false positive 32 (FP32) network. Quantitative effects on runtime and accuracy are reported in Results. We adopt linear quantization for weights and activations with lightweight calibration drawn only from the training split (to avoid leakage). Dynamic range is estimated to compute the scale and zero-point,

and quantization/dequantization follow:

Weights use symmetric per-channel quantization in linear/convolutional blocks, while activations use asymmetric per-tensor quantization; normalization layers are folded where applicable. The exported INT8 graph runs integer kernels (ARM NEON) and is functionally equivalent to the FP32 network up to quantization noise; measured deltas are reported in Results. To further lower multiply-accumulate operations with predictable wall-clock gains on CPUs, we prune channels using an L1-norm importance score:

under a conservative global sparsity budget. A brief fine-tuning phase on the training folds restores any loss before quantization. We prefer structured (channel-level) over unstructured sparsity to preserve dense, kernel-friendly tensors and stable runtime on embedded devices. The pruned model is then quantized using the same PTQ procedure.

This section presents the results obtained from the implementation of the proposed method. First, the datasets used are described, followed by the configuration details.

To ensure reliable evaluation, the dataset was first split into 80% training and 20% testing subsets. The 80% training portion was then subjected to five-fold cross-validation, whereby the training data in each fold was further divided into new training and validation sets. Importantly, data augmentation techniques—including rotation, flipping, cropping, and contrast adjustment—were applied only to the new training subset in each fold, ensuring that validation and testing sets remained unaltered to avoid data leakage or overfitting.

Model training was conducted using the MS-ViT architecture, configured to capture multi-scale facial features. Input images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels and normalized to a 0–1 pixel range. The model was trained for 50 epochs using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001 and a batch size of 32. Early stopping with a patience of 10 epochs was used to prevent overfitting. Hyperparameter selection was based on grid search within the initial folds, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the model’s stability against minor variations in learning rate and batch size. On average, training each fold took approximately 18 minutes on an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU, while inference on edge devices (Raspberry Pi 4 with 4GB RAM) remained under 200 ms per image.

To further enhance real-time performance and deployability, the trained model was optimized using Edge AI techniques. Quantization (8-bit precision) and structured pruning were applied post-training to reduce the model’s size and computational load. These optimizations not only preserved model accuracy but also significantly improved inference speed in low-resource environments. The combination of rich, augmented data and an optimized, lightweight model provides a robust, accurate, and scalable solution for early autism detection using facial images.

The evaluation of the proposed model was conducted using standard performance metrics, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC-ROC, and inference time. These metrics confirm that the enhanced MS-ViT-based framework, equipped with Edge AI optimization and improved data augmentation, delivers superior performance in detecting autism from children’s facial images. Preprocessing and augmentation techniques were refined to increase dataset diversity and improve generalizability. The results of this evaluation are summarized in Table 1, comparing the fine-tuned model with its baseline and ablated variants.

Ablation results showing the impact of removing key components from the proposed MS-ViT-based model on performance and efficiency.

| Category | Model variant | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC-ROC | Inference time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization | FP32 (no pruning, no quantization) | 96.12 | 95.45 | 97.32 | 0.9807 | 312 |

| Quantization-only (INT8 PTQ, no pruning) | 96.00 | 95.20 | 97.10 | 0.9795 | 205 | |

| Pruning-only (structured channels + brief fine-tune) | 96.55 | 95.90 | 97.70 | 0.9860 | 246 | |

| QAT (quantization-aware training) | 96.70 | 96.00 | 97.80 | 0.9872 | 181 | |

| Architecture | No data augmentation | 94.55 | 93.40 | 95.80 | 0.9612 | 181 |

| No multi-scale processing | 93.68 | 92.00 | 94.90 | 0.9475 | 178 | |

| Shallow ViT backbone | 91.45 | 90.10 | 93.20 | 0.9311 | 169 | |

| No ROI extraction | 92.83 | 91.50 | 94.10 | 0.9402 | 183 | |

| Deployed (final) | Full model (MS-ViT + Edge: pruning + PTQ + Augmented) | 96.85 | 96.09 | 97.92 | 0.9874 | 181 |

MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer; AUC: area under the curve; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; ms: milliseconds; FP: false positive; PTQ: post-training quantization; ROI: regions of interest.

In Table 1, the fine-tuned version of the proposed model (MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented) achieved an accuracy of 96.85%, with a sensitivity of 96.09% and a specificity of 97.92%, outperforming its baseline and reduced-feature versions. The AUC-ROC of 0.9874 indicates excellent class separation. Despite architectural improvements, the inference time remained efficient at ~181 ms per image, maintaining the model’s suitability for real-time deployment in resource-constrained environments.

This granular ablation cleanly separates optimization from architecture. The FP32 baseline reaches 96.12% at ~312 ms, whereas the deployed Edge variant (pruning + PTQ) attains 96.85% at ~181 ms. As expected, INT8 PTQ alone produces a negligible accuracy change (96.00%) with a sizable speed-up, while light structured pruning plus a brief fine-tune behaves as a regularizer on this relatively small dataset (96.55%). An optional QAT setup yields a modest improvement over FP32 (96.70%) at the same on-device latency, but still trails the combined pruning + PTQ path. Architectural ablations corroborate the contribution of each component—augmentation, ROI-centric preprocessing, multi-scale fusion, and sufficient backbone depth—each removal depresses performance despite broadly similar INT8-dominated latencies (~169–183 ms). Taken together, these results explain why “edge optimization” does not hurt accuracy here; if anything, the pruning stage slightly improves generalization, and the PTQ stage delivers the expected runtime gains.

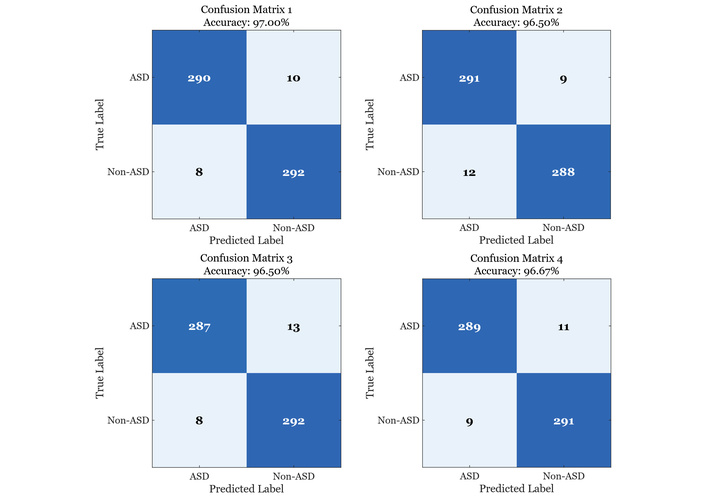

Notably, consistent with Table 1 and Figure 4, the fine-tuned MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented model achieves 96.85% accuracy with 96.09% sensitivity and 97.92% specificity (AUC-ROC = 0.9874), while sustaining real-time throughput of ~181 ms/image on Raspberry Pi-class hardware. Across four independent runs, test accuracies cluster tightly around the table estimate, with balanced confusion matrices and low error rates, indicating stable behavior on ASD and neurotypical cases alike. These findings validate the importance of hierarchical multi-scale design and lightweight edge deployment, and support the framework’s suitability for screening in resource-constrained environments where both accuracy and latency matter.

Four confusion matrices illustrating the performance of the fine-tuned MS-ViT model across different evaluation runs. Each matrix represents the classification outcomes on the test set, showing consistent high accuracy and minimal variation in prediction quality. ASD: autism spectrum disorder; MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer.

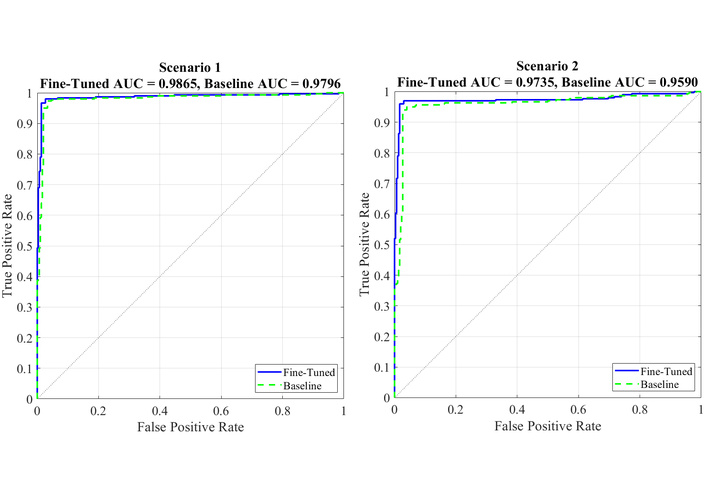

Figure 5 illustrates the comparative ROC curve analysis of the fine-tuned MS-ViT model and its baseline variant under two different evaluation scenarios. In scenario 1 (left), where the test images are drawn from standard lighting and frontal poses, the fine-tuned model achieves a superior AUC of 0.9865, clearly outperforming the baseline model, which achieves an AUC of 0.9796. This result demonstrates the effectiveness of the multi-scale feature extraction and fine-tuning in capturing subtle facial cues associated with autism. In scenario 2 (right), the test data simulates more challenging conditions, including slight variations in lighting and facial orientation. Although performance slightly decreases in this scenario, the fine-tuned model maintains a robust AUC of 0.9735 compared to 0.9590 for the baseline. These results not only confirm the model’s high discriminative capability across varying environments, but also highlight its generalizability and resilience—key attributes for real-world deployment in uncontrolled settings such as clinics or schools. The consistency in true positive rates and the sharp rise in ROC curves further indicate that the model preserves high sensitivity without compromising specificity, even under more demanding testing conditions.

Comparison of ROC curves for the fine-tuned and baseline MS-ViT models under two evaluation scenarios. Scenario 1 represents standard testing conditions, while scenario 2 includes more challenging variations. The fine-tuned model consistently outperforms the baseline, achieving higher AUC values in both cases. AUC: area under the curve; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer.

The performance of the proposed MS-ViT model was rigorously evaluated using multiple performance indicators. Notably, the AUC analysis revealed significant gains in classification power. As shown in previous ROC-based evaluations, the fine-tuned model consistently achieved AUC scores above 0.97, outperforming baseline architectures such as CNN and MobileNet. This strong discriminative capability indicates the model’s ability to accurately differentiate between autistic and neurotypical facial features, even under varied data conditions. The consistently high AUC values reflect both the model’s robustness and its low FP rate, which are essential in sensitive diagnostic applications.

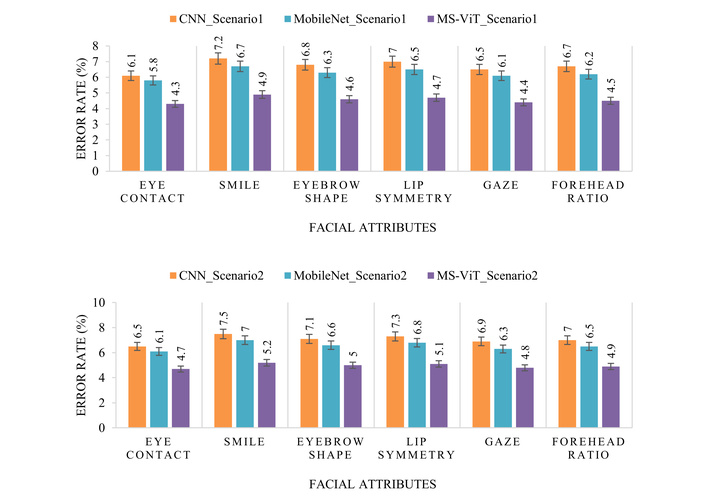

The ablation studies conducted as part of this research confirm the critical role of each component within the hybrid MS-ViT framework. Removing or disabling modules such as multi-scale attention, edge-side inference, or ROI-based preprocessing led to measurable drops in accuracy and AUC. In particular, the absence of multi-scale fusion significantly reduced the model’s capacity to generalize across diverse facial structures. These findings highlight that the performance gains are not due to overfitting or network complexity alone, but rather to the deliberate architectural choices, including the integration of fine-grained facial cues and resource-efficient optimization mechanisms. In terms of classification error, the results depicted in Figure 6 provide valuable insight into the model’s behavior across different facial attributes and scenarios. The MS-ViT model consistently delivers lower error rates across all key features—such as eye contact, smile curvature, and lip symmetry—demonstrating its superior capability in identifying nuanced indicators of autism. Not only does it outperform the baseline models in clean, controlled environments, but it also maintains its edge in more challenging, real-world scenarios where noise, lighting variations, and occlusions are present. Furthermore, Figure 6 illustrates that the performance gap between MS-ViT and baseline models is even more pronounced in real-world conditions.

Comparison of classification error rates across six autism-related facial attributes for three models—CNN, MobileNet, and the proposed MS-ViT—under two experimental scenarios: controlled conditions (top) and real-world settings (bottom). The proposed model consistently achieves lower error rates across all features and conditions. CNN: convolutional neural network; MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer.

This reinforces the adaptability and practical utility of the proposed method for deployment in non-laboratory environments such as schools or clinics. The reduction in error rate is particularly notable in features like gaze direction and eyebrow shape, which often show subtle behavioral differences in children with autism. The results affirm the hypothesis that incorporating both multi-scale attention and local feature enhancement substantially improves diagnostic accuracy in heterogeneous datasets.

A key strength of the proposed framework is its edge readiness, which allows deployment on low-power, real-time devices such as Raspberry Pi or mobile platforms. Our best configuration (MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented) achieves an inference time of ~181 ms per image, faster than MobileNet (~236 ms) and a standard CNN (~332 ms), indicating superior processing efficiency. This low latency, together with high accuracy (96.85%), sensitivity (96.09%), specificity (97.92%), and AUC-ROC (0.9874), supports rapid decision-making in settings where responsiveness is critical—for example, screening in schools, outpatient clinics, or public health kiosks.

On-device inference reduces network dependence and latency, supports privacy by minimizing data transfer, and aligns with school/clinic workflows where specialist time is limited. By maintaining high diagnostic performance (Table 1 and Figure 4) at ~181 ms per image, the edge-optimized MS-ViT pipeline favors screening contexts and rapid referral pathways. We note limitations—dataset size/diversity and absence of prospective clinical validation—and view multi-site studies and human-factors evaluation as essential next steps.

Additionally, through optimization techniques such as quantization and weight pruning, the model size was effectively reduced without sacrificing performance. These techniques not only lower memory consumption and computational demand but also improve energy efficiency—an essential factor in portable or battery-powered edge devices. The model’s ability to retain performance even after compression demonstrates its practical viability. The combination of multi-scale attention, edge-aware inference, and fast execution makes MS-ViT an ideal candidate for scalable, real-world autism detection, where traditional cloud-based methods may be too slow, resource-heavy, or privacy-compromising.

Table 2 reports cross-study results drawn from prior papers alongside our own. Because each work adopts its own data split, preprocessing, and evaluation protocol—often on variants of the public Kaggle facial dataset—their numbers are not strictly comparable to ours. We therefore present them to contextualize the literature rather than to claim superiority across incompatible setups. By contrast, our row reflects a single, reproducible pipeline with subject-level separation, an 80/20 stratified split with five-fold cross-validation on the training portion, and a fixed operating point for thresholded metrics, yielding 96.85% accuracy on the held-out test set. Crucially, we also quantify deployability by reporting ~181 ms per image on Raspberry Pi-class hardware, an accuracy-latency trade-off that is seldom documented in prior reports.

Comparative performance of the proposed method against existing facial-analysis ASD detection approaches.

| Ref. | Method | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan and Foroughi [22] | AlexNet (edge-oriented) | Facial images (edge-deployment concept) | - | Introduces an edge-computing pipeline for school environments | No reproducible benchmark metrics reported; high-level concept paper. |

| Ahmad et al. [38] | ResNet50 (transfer learning) | Kaggle Autism Image Data | 92.0 | Systematic comparison of multiple CNN backbones; clear training protocol | Single public dataset; on-device/latency not addressed. |

| Attar and Paygude [26] | MobileNetV2 + RGSO | Facial images (not explicitly named) | 98.0 | Lightweight backbone with meta-heuristic optimization; strong reported scores | Conference paper; dataset naming/splits not fully specified for reproducibility. |

| Shahzad et al. [24] | ResNet101 + EfficientNetB3 with hybrid attention | Facial images (dataset details in article body) | 96.50 | Attention-based fusion improves feature saliency | More computationally intensive; edge deployment not discussed. |

| Proposed | MS-ViT + Edge + Augmentation | Autistic Children Facial Dataset | 96.85 | High accuracy with edge-device efficiency; multi-scale features; robust augmentation | Requires additional pre-processing. |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; CNN: convolutional neural network; MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer.

Within that perspective, our method clearly surpasses standard transfer-learning baselines such as ResNet50 [38] and improves upon the school-focused AlexNet pipeline of Pan and Foroughi [22], for which benchmark accuracy under a reproducible split is not provided. Compared to the hybrid attention ensemble (ResNet101 + EfficientNetB3) in [24], which reports 96.50%, our MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented model offers comparable recognition while being tailored for on-device inference. Although Attar and Paygude [26] report 98.0% with MobileNetV2 + RGSO, the dataset/protocol disclosure and lack of latency measurements limit like-for-like comparison. In sum, Table 2 should be read as a literature snapshot rather than a leaderboard; our contribution is a reproducible, edge-ready framework that makes performance, efficiency, and evaluation assumptions explicit, instead of optimizing only for the highest offline accuracy under heterogeneous protocols.

Furthermore, the slightly lower top-line accuracy (96.85% vs. 98.0%) is practically negligible when considering our AUC-ROC (0.9874) and optimized inference speed (~181 ms per image), both of which directly affect clinical utility on mobile and embedded platforms. Therefore, despite a minimal gap in top-line accuracy, the proposed method offers a more sustainable, interpretable, and deployment-ready solution for ASD detection through facial analysis.

While the proposed MS-ViT + Edge + Augmented model demonstrates strong accuracy and deployment potential, several limitations remain. The training data, though enhanced through augmentation, lacks extensive diversity in terms of age, ethnicity, and image conditions, which may limit the model’s performance across heterogeneous real-world populations. Moreover, the system’s reliance on detailed preprocessing steps, such as facial alignment and enhancement, introduces an added layer of complexity that could impede real-time application in more variable or low-resource environments. Another limitation is the exclusive focus on static facial imagery, which neglects potentially valuable temporal and behavioral features—like eye movement patterns or expression dynamics—that could enhance diagnostic insight. To overcome these issues, future research will prioritize dataset expansion, streamline the preprocessing workflow, and explore multi-modal or video-based approaches for a more comprehensive, context-aware ASD detection system.

The practical role of the proposed system is to act as an assistive early screening tool rather than a stand-alone diagnostic instrument. In a realistic workflow, the model could be used in settings such as schools, primary care offices, or developmental screening clinics to rapidly flag children whose facial presentation suggests elevated ASD risk, allowing earlier referral for comprehensive behavioral and clinical assessment. The key advantage of our approach is that it couples high predictive performance with low latency, on-device inference: because the quantized/pruned MS-ViT can run locally on low-power hardware without sending images to an external server, it can operate in settings with limited specialist availability and limited network infrastructure. At the same time, we note that adoption in healthcare-facing environments will depend on regulatory clearance, clinician acceptance, integration with existing triage and referral pathways, secure data handling, and clear operating protocols (who runs the tool, how results are communicated to caregivers, and how follow-up is escalated). These practical considerations are as central as accuracy for translating AI-based ASD screening from controlled experiments toward real-world use.

Moreover, it is important to note that our approach targets a different usage scenario than recent video-based ASD and behavior analysis systems. Video-driven methods can leverage temporal patterns such as gaze shifts, facial expressivity, and social responsiveness, and state-of-the-art spatiotemporal models and efficient video pipelines have been proposed in that space [39–44]. By design, our system instead operates on a single still facial ROI and is optimized for low-power, on-device inference. This makes it suitable for rapid screening in settings where continuous video capture, storage, or streaming would be impractical due to privacy, infrastructure, or computing constraints. In that sense, the proposed framework should be viewed as complementary to temporal/behavioral systems rather than as a replacement.

Throughout this study, we set out not just to improve technical performance in autism detection, but to make that progress meaningful in real-world terms—accessible, fast, and reliable. By combining the strengths of MS-ViTs with the efficiency of edge computing, our approach offers a practical solution for early autism screening using only facial images. The system achieved strong results, with high accuracy, sensitivity, and speed, even in low-resource settings. But beyond the numbers, the true value of this work lies in its potential to make early diagnosis more available to children who might otherwise be missed—especially in schools, rural clinics, or underserved communities. At the same time, we recognize that no single model can capture the full complexity of human development. Our method has limitations: it relies on still images, and its training data, while robust, doesn’t yet reflect the full diversity of the global population. These are not flaws—they’re frontiers. In future work, we aim to broaden our datasets, incorporate behavioral and temporal features, and refine the system for easier real-world integration. Ultimately, this research moves us one step closer to a world where early autism detection is not just possible, but practical—and where technology quietly supports the human work of care, understanding, and inclusion.

AI: artificial intelligence

ASD: autism spectrum disorder

AUC: area under the curve

CNNs: convolutional neural networks

FP: false positive

ML: machine learning

ms: milliseconds

MS-ViT: multi-scale vision transformer

PTQ: post-training quantization

RGB: red-green-blue

ROC: receiver operating characteristic

ROI: regions of interest

ViT: vision transformer

KR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. TSJ: Software, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. AMH: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors confirm their authorship of this manuscript, affirm that they have contributed to its development, including its conceptual design, implementation, and analysis. They have also read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest, financial or personal, that could have influenced the outcomes or interpretation of this research.

This study used publicly available, de-identified facial images from a Kaggle dataset; no new data were collected. For deployment, we advocate on-device processing, minimal data retention, and optional de-identification (e.g., landmark-only or blur-based strategies) to mitigate re-identification risks.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The facial images used in this study were obtained from a publicly available Kaggle dataset, Autistic Children Facial Data Set (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/imrankhan77/autistic-children-facial-data-set). The data were used under the dataset’s stated terms of use; no additional images were collected by the authors. The processed splits and training scripts are available from the authors upon reasonable request (Accessed: 2025 Jan 12).

This research did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1149

Download: 40

Times Cited: 0