Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, Kingston 07, Jamaica

Affiliation:

2Bodles Agricultural Research Station, A2, Old Harbour 18, Jamaica

3Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, Kingston 07, Jamaica

Affiliation:

3Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, Kingston 07, Jamaica

4Caribbean Centre for Research in Bioscience, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, Kingston 07, Jamaica

Email: noureddine.benkeblia@uwimona.edu.jm

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7477-2092

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2026;4:1010109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2026.1010109

Received: June 19, 2025 Accepted: December 03, 2025 Published: January 22, 2026

Academic Editor: Miguel Herrero, Institute of Food Science Research (CIAL-CSIC), Spain

Aim: Because sweet potato is an important staple food crop worldwide, particularly in developing countries, the cultivar has a great influence on the nutritional quality and storage capability of the roots. The aim of this study was to characterize and segregate the sweet potato diversity of 18 selected cultivars grown in Jamaica.

Methods: Quality attributes were estimated by determining carotenoids, anthocyanins, dry matter, and ash, parameters used to characterize eighteen (18) different cultivars of sweet potato phenotypically. ANOVA and LSD analyses were used to analyse data. Furthermore, PCA and HCA analyses were used to compare and segregate the studied cultivars.

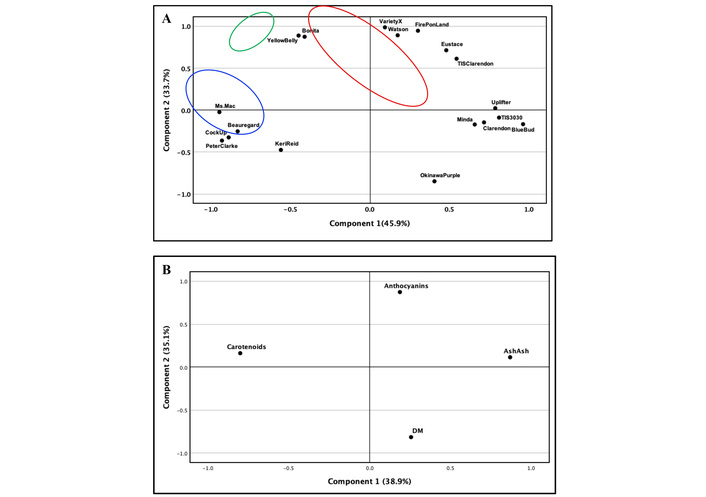

Results: Results showed that four cultivars contained more than 10 μg/g fresh weight of carotenoids, and in nine cultivars, anthocyanin content was higher than 500 μg/g fresh weight. Dry matter varied from 21.96% to 46.46%, and ash content ranged from 0.09 to 1.2%. The segregation of the cultivars revealed two principal components, with PC1 explaining 45.9% and PC2 explaining 33.7%. The classification based on their nutritional contents showed PC1 explaining 38.9% and PC2 explaining 35.1% of the total variance. On the other hand, HCA and heatmapping evidenced the presence of three main groups, namely anthocyanins, carotenoids, and ash.

Conclusions: The findings of this study advanced our existing knowledge on the numerous cultivars of sweet potato grown in Jamaica and validated the diversity of their nutritional profile. From these data, we can recommend that some cultivars of sweet potato are suitable for processing and could also contribute significantly to improving local human nutrition.

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) is the most consumed root crop in the world. It is thought to have originated from Latin America, and one of the oldest crops known to the region. Two types of sweet potato are known: (i) the “dry-fleshed” type with a yellow, ivory, white, or purple flesh and which is very popular in the Caribbean, and (ii) the “moist-fleshed” type with a red-skinned and dark-orange flesh. Among these two types of sweet potato, more than four hundred cultivars are known worldwide, differing in skin colour and flesh.

Sweet potato, as a starchy tuber crop, possesses the highest energy value after cassava compared to other root and tuber staples. The most interesting nutritional quality of sweet potato is its content of β-carotene (provitamin A) and anthocyanins in some purple and dark varieties and cultivars. In previous studies, the content of sweet potato in carotenoids has been reported to vary from low, medium, and high carotenoid cultivars, ranging from 50 to 260 µg/g fresh weight (FW), with an average of circa 130 µg/g FW. Most of these high carotenoid values have been reported in the Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato (OFSP) root, a biofortified cultivar with beta-carotene. The analysis of the β-carotene content of twenty-five sweet potato cultivars from seven different countries, Takahata et al. [1], found β-carotene values ranging from 11 to 265 µg/g FW. The analysis of the β-carotene of eighteen cultivars of sweet potato grown in Hawaii also showed high levels ranging from 1 to 6 μg/g FW [2]. Other studies also reported different levels of β-carotene in sweet potato, ranging from 0 to 90 µg/g FW [3]. Compared to carotenoid content, anthocyanin content in sweet potato has been studied less extensively. Steed and Truong [4] compared the anthocyanin content of one locally grown purple-fleshed sweet potato puree and found contents varying between 515 and 1,747 µg/g FW. Moreover, ash and dry matter (DM) of sweet potato also vary considerably with genotype, environment, and growing conditions [5–7].

In the Caribbean region, sweet potato is grown in every island; however, Jamaica, Barbados, and St Vincent and the Grenadines are the largest producers. In Jamaica, numerous cultivars of sweet potato are distinguished locally, and some are very popular, such as Uplifter, Quarter, Million, Eustace, Big Red, Clarendon, and Blue Bud, while the Beauregard cultivar was introduced a few years ago to boost sweet potato production mainly for the export market. Nevertheless, Jamaican consumers give preference to smooth, red skin types with white flesh, and Uplifter, with its yellow flesh, is in high demand by the ethnic population in the export market. Indeed, markets for the Jamaican cultivars of sweet potato varieties are already established in the UK and Canada, and these cultivars are favoured by the ethnic population in these countries. However, there is no data reporting the nutritional qualities of the locally grown sweet potato, except for the Beauregard, which was imported and introduced from the USA to allow Jamaica to expand its sweet potato market. Indeed, the interest in this cultivar is due to the time to harvest being slightly shorter than the USA’s period of harvest, and it is not affected by frost since it is grown in a tropical region, unlike the USA. In an effort to expand the export of agricultural produce, Jamaica launched a large programme by introducing different cultivars, particularly orange-flesh sweet potato varieties such as the Beauregard variety for export, in response to an expressed demand for this variety from foreign markets. The introduction of this OFSP cultivar was also targeting to alleviate vitamin A deficiency observed among Jamaican children, which was estimated to average 21% in 1991 but declined to 11% in 2013 in the Caribbean region [8].

Although Jamaica is among the largest producers of sweet potato, no study has investigated the proximate composition contents of the different cultivars grown in the island, except the one reported by Bahado-Singh et al. [9]. These authors determined the total sugars, fat, proteins, and ash content of 10 different cultivars commonly consumed in Jamaica. Because of this nutritional trait, sweet potato might play an important role in human diets as a value‐added product in food and nutrition systems, particularly in countries affected by vitamin A deficiency and its alleviation [10, 11].

Considering the importance of sweet potato in the diet of many populations around the world and the Caribbean community more specifically, and the increasing consumption and the promising health benefits of this agricultural produce, there is a need to screen and clarify some nutritional traits of the numerous cultivars of sweet potato grown in the island. Because no previous referenced study investigated carotenoids and anthocyanins contents of sweet potato cultivars grown in Jamaica, and to better understand and cover the knowledge gap, this study aimed to investigate the carotenoids (provitamin A) and anthocyanins contents of eighteen (18) cultivars of sweet potato grown across Jamaica. The findings will be compared with the counterpart sweet potato cultivars grown in other regions to further evaluate and compare their nutritional traits. The data will also help (i) in improving the nutritional status of the local population, particularly pre- and primary school children in Jamaica and the Caribbean, and (ii) develop processed products such as fries and chips, among others.

The plant material of sweet potatoes—18 cultivars—was specifically selected and supplied by Bodles Research Station, Old Harbour, St. Catherine, Jamaica. The cultivars have been selected because of their predominance in the local market, and their agronomic and marketability are appreciated by the local farmers. The samples were transported to the laboratory, washed, left to drain at room temperature for two hours, and then frozen at –20°C until use.

The chemicals used in this study, methanol and HCl, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). The reagents and mixtures were freshly prepared prior to the analyses.

Total carotenoids and anthocyanins were extracted by the method described by Lindoo and Caldwell [12] using acidified methanol for optimal extraction with slight modifications. The modifications consist of extracting carotenoids and anthocyanins at room temperature for four hours, after samples have been homogenised in the extraction solvent. Briefly, 50 g of frozen sweet potato samples were homogenized with 75 mL of methanol:water:concentrated HCl (MeOH:H2O:HCl/80:20:1) and left at room temperature to stand for 4 hours to ensure better stability and recovery rate (> 90%) of carotenoids. After, the homogenate was filtered through a cheesecloth. The filtrate was made up to 200 mL using acidified methanol. For the spectrophotometric analysis, 10 mL of the extracts were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 3 minutes, and the collected supernatants were used for carotenoids and anthocyanins analyses.

Total carotenoid content was analysed using the method described by Sumanta et al. [13]. A sample of 0.5 mL extract was mixed with 4.5 mL of the extraction solvent (MeOH:H2O:HCl) and vortexed for 10 s, and the mixture was used to assess carotenoid content. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 470 nm, 652 nm, and 665 nm using a Genesys spectrophotometer (Model Genesys 10S, Thermo-Fisher Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and the extraction solvent (MeOH:H2O:HCl) was used as a blank. After calculating the concentrations of chlorophyll-a (C-a) and chlorophyll-b (C-b), total carotenoid content was calculated using the following equation:

Where A is absorbance at the indicated wavelength (470 nm, 652.4 nm, and 665.2 nm), C-a = chlorophyll-a, and C-b = chlorophyll-b, c+x stands for carotenoids and xanthophylls.

Total anthocyanins were extracted by the same method used for the extraction of carotenoids and analysed using the method described by Lee et al. [14]. To perform anthocyanin analysis, centrifuged extracts were diluted using two pH buffers, one of pH 1.0 buffer (0.025 M potassium chloride) and the other of pH 4.5 buffer (0.4 M sodium acetate), and left to stand for 20–50 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the absorbance of the two test portions diluted with pH 1.0 buffer [C(a)] and pH 4.5 buffer [C(b)] was measured at 520 and 700 nm versus a blank cell filled with distilled water using Genesys spectrophotometer (Model Genesys 10S, Thermo-Fisher Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Total monomeric anthocyanins are determined by the following equations:

Where A is absorbance from Eq. 1, MW is the molecular weight of monomeric anthocyanins (MW = 449.2), ε is the molar absorptivity of cyanidin-3-glucoside (ε = 26,900), DF is the dilution factor, FV is the final volume of the extract, and L is the path length.

DM of the samples was determined by the method described by Yildirim et al. [15]. Samples of 5 g were dried at 65°C until constant weight. The final and initial weight differences were used to calculate the DM percentage. Ash content of the samples was determined using the method described by the AOAC [16]. Samples of 5 g were placed in a crucible and dried in an oven at 105°C for 3 h. Then, the samples were allowed to incinerate in a pre-heated muffle furnace at gradually increasing temperatures from 350°C until a temperature of 500°C for 2 h. The final and initial weight differences were used to calculate ash content.

Data were treated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the data of the different cultivars, and differences among means were determined by the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test with significance defined at P < 0.05. The data were standardised, and PCA (principal component analysis) and HCA (hierarchical cluster analysis) were performed using SPSS software package (version 29.2. IBM Corp., New York, USA). In order to ensure that groups share good correlation, for the HCA analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficients were selected as the measurement between the cultivars, the furthest neighbour as the clustering method, and the Squared Euclidean distance (SE) for interval measurement. The clustered heatmap was generated using SRPLOT free software (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/srplot).

Total carotenoids in the different cultivars of sweet potato varied significantly from as low as less than 0.5 μg/g FW in Cock Up cultivar to 79.35 μg/g FW in the Beauregard variety (Table 1). The classification to low, medium and high carotenoid contents shows six cultivars [Eustace, Fire on Land, Clarendon, Cock Up, TIS Clarendon, and Watson (Unknown2)] contained low carotenoids level (less than 5 μg/g FW), eight cultivars [Keri Reid, TIS3030, Blue Bud, Ms. Mac, Minda and Yellow Belly, Bonita (Unknown1) and Variety X] contained medium level of carotenoids (5 to 10 μg/g FW), and four cultivars (Okinawa Purple, Uplifter, Peter Clarke and Beauregard) contained more than 10 μg/g FW.

Total carotenoid content (μg/g fresh weight) of the sweet potato cultivars.

| Cultivars | Lowest content | Highest content | Average ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beauregard | 74.5 | 80.37 | 79.35 ± 4.42a |

| Okinawa Purple | 37.02 | 37.09 | 37.04 ± 0.04b |

| Peter Clarke | 20.00 | 20.30 | 20.10 ± 0.17c |

| Uplifter | 14.56 | 14.65 | 14.62 ± 0.05c |

| Blue Bud | 9.77 | 9.82 | 9.79 ± 0.03cd |

| TIS3030 | 9.30 | 9.45 | 9.35 ± 0.03d |

| Yellow Belly | 9.21 | 9.28 | 9.23 ± 0.04d |

| Keri Reid | 7.37 | 7.49 | 7.44 ± 0.07d |

| Ms. Mac | 7.23 | 7.26 | 7.24 ± 0.02d |

| Minda | 6.29 | 6.45 | 6.37 ± 0.08d |

| Variety X | 4.40 | 6.10 | 5.53 ± 0.98de |

| Bonita (Unknown1) | 4.98 | 5.16 | 5.09 ± 0.09e |

| Fire on Land | 4.09 | 4.14 | 4.11 ± 0.03e |

| Clarendon | 2.64 | 2.67 | 2.65 ± 0.02e |

| TIS Clarendon | 1.49 | 1.62 | 1.58 ± 0.08f |

| Watson (Unknown2) | 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.25 ± 0.01f |

| Eustace | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.74 ± 0.0g |

| Cock Up | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 |

Means followed by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Means sharing a common superscript letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Among the cultivars analysed in this study, the Okinawa Purple cultivar had the highest anthocyanin content, yielding 3,382.88 μg/g FW, while in Ms. Mac, Cock Up, and Beauregard cultivars, anthocyanins were not detected (Table 2). Okinawa Purple cultivar was the only purple-fleshed cultivar analysed in this study, and as such, it was expected that this cultivar would contain a higher level of anthocyanins. In addition to the flesh colour of the cultivar, the colour intensity of the flesh also aided in the assumption that anthocyanin content would be very high.

Total anthocyanin content (μg/g fresh weight) of the sweet potato cultivars.

| Cultivars | Lowest content | Highest content | Average ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okinawa Purple | 3,372.94 | 3,392.83 | 3,382.88 ± 9.95a |

| Clarendon | 2,615.62 | 2,756.22 | 2,685.92 ± 70.30b |

| Minda | 1,516.75 | 1,598.83 | 1,557.80 ± 41.0c |

| TIS3030 | 1,499.89 | 1,587.91 | 1,543.90 ± 44.01c |

| Eustace | 1,190.78 | 1,216.59 | 1,203.68 ± 12.90c |

| Keri Reid | 1,187.34 | 1,224.51 | 1,205.90 ± 18.61c |

| Blue Bud | 1,090.11 | 1,116.19 | 1,103.15 ± 13.01c |

| Uplifter | 953.89 | 987.34 | 970.62 ± 16.71cd |

| Watson (Unknown2) | 648.46 | 672.22 | 660.34 ± 11.90d |

| Peter Clarke | 205.54 | 222.24 | 213.89 ± 8.35e |

| Yellow Belly | 128.12 | 138.23 | 133.19 ± 5.06f |

| Fire on Land | 72.8 | 82.71 | 77.73 ± 4.96f |

| Bonita (Unknown1) | 61.84 | 67.63 | 64.73 ± 2.90fg |

| TIS Clarendon | 34.58 | 39.42 | 37.00 ± 2.42g |

| Variety X | 14.26 | 16.1 | 15.18 ± 0.92h |

| Ms. Mac | nd | nd | nd |

| Cock Up | nd | nd | nd |

| Beauregard | nd | nd | nd |

*nd: not detected. Means followed by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Means sharing a common superscript letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

The cultivar Clarendon followed Okinawa Purple with an anthocyanin content averaging 2,685.92 μg/g FW. This cultivar had a cream flesh colour, and the observed anthocyanin content may be due to the composition of the cultivar, which is not exhibited by its appearance. Beauregard cultivar was one of the three cultivars in which anthocyanins were not detected. Beauregard cultivar is characterized by an orange flesh colour and shows the highest carotenoid content among the analysed cultivars. This indicates that sweet potatoes with deep orange flesh colour do not contain or contain much less anthocyanins, which are present in other sweet potato cultivars. Additionally, in Cock Up cultivar, no anthocyanins were detected, while carotenoid content was less than 1 μg/g FW. This indicates that this cultivar is not a significant source of anthocyanins or carotenoids and, therefore, it is not suitable as an ingredient to nutritionally enhance other food products.

DM of the different cultivars varied significantly (Table 3). All the investigated cultivars yielded more than 30% DM except the Okinawa cultivar, which yielded 21.96%. On the other hand, thirteen cultivars yielded more than 40% of DM. Comparatively, cultivar Watson showed the highest DM content (46.46%) while the Okinawa Purple cultivar showed the lowest DM content (21.96%).

Dry matter (DM) of the sweet potato cultivars.

| Cultivars | DM/% |

|---|---|

| Watson | 46.46 ± 2.06a |

| Eustace | 45.55 ± 2.01a |

| Beauregard | 44.96 ± 1.73a |

| Clarendon | 44.04 ± 1.86a |

| Keri Reid | 43.73 ± 1.87a |

| Bonita | 43.72 ± 1.41a |

| Fire on Land | 42.00 ± 1.67a |

| Ms. Mac | 41.96 ± 1.42a |

| Minda | 41.66 ± 1.71a |

| TIS3030 | 41.63 ± 1.59a |

| Variety X | 41.37 ± 1.645a |

| Yellow Belly | 41.35 ± 1.58a |

| Peter Clarke | 40.74 ± 1.63ab |

| Blue Bud | 38.05 ± 0.98b |

| Cock Up | 37.48 ± 1.67b |

| TIS Clarendon | 35.98 ± 1.02bc |

| Uplifter | 33.71 ± 0.67c |

| Okinawa Purple | 21.96 ± 0.14d |

Means followed by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Means sharing a common superscript letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

The Eustace cultivar had the highest ash content, yielding 1.20%, and the Peter Clarke cultivar the lowest, yielding 0.09% (Table 4). The ash content of the cultivar with the highest carotenoid content (Beauregard) and the highest anthocyanin content (Okinawa Purple) was much lower than cream coloured flesh cultivars such as Variety X, Eustace, and Fire on Land. On the other hand, the high ash content observed in the cream-coloured flesh cultivars might be due to the physiochemical composition of the cultivars and indicative of the presence of numerous minerals in sweet potato cultivars. Conversely, the low ash content observed in the purple and orange fleshed cultivars might be related to poor mineral content in comparison to their cream-coloured flesh counterparts.

Ash of the sweet potato cultivars.

| Cultivars | Ash/% |

|---|---|

| Eustace | 1.20 ± 0.24a |

| Uplifter | 1.14 ± 0.13a |

| Fire on Land | 1.19 ± 0.06a |

| Watson | 1.13 ± 0.17ab |

| Clarendon | 1.10 ± 0.06ab |

| Variety X | 0.94 ± 0.01b |

| TIS3030 | 0.89 ± 0.07bc |

| Blue Bud | 0.83 ± 0.07bc |

| Minda | 0.81 ± 0.10bc |

| Bonita | 0.71 ± 0.08c |

| Yellow Belly | 0.69 ± 0.06c |

| TIS Clarendon | 0.68 ± 0.16c |

| Okinawa Purple | 0.42 ± 0.06d |

| Cock Up | 0.15 ± 0.06e |

| Beauregard | 0.14 ± 0.03e |

| Ms. Mac | 0.13 ± 0.03e |

| Keri Reid | 0.11 ± 0.03e |

| Peter Clarke | 0.09 ± 0.04e |

Means followed by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Means sharing a common superscript letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Here, we are describing the use of the statistical hypothesis testing of factor loading in PCA using the analysed factors of the eighteen cultivars of sweet potato (Figure 1). PCA of the studies’ cultivars revealed two principal components and were cumulatively accounted for 79.6% of the total variance, with PC1 explaining 45.9% and PC2 explaining 33.7% of the total variance, respectively (Figure 1A). On the other hand, Figure 1B illustrates the corresponding loadings plot showing carotenoids, anthocyanins, DM, and ash for the classification of the different cultivars by PCA analysis. PCA revealed two principal components and were cumulatively accounted for 74% of the total variance, with PC1 explaining 38.9% and PC2 explaining 35.1% of the total variance, respectively.

Principal component analysis (PCA) scores plot (A) and loadings plot (B) of the different varieties of sweet potato.

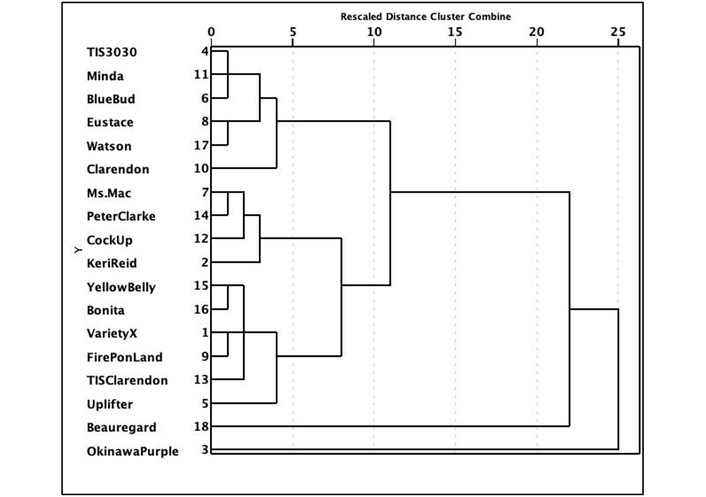

To further clarify the difference between the studied cultivars, HCA was performed, hierarchically clustering each cultivar based on their anthocyanins, carotenoids, DM, and ash contents (Figure 2). Pearson’s coefficients were calculated to determine the significant correlations between the eighteen cultivars. In order to also have a clear visualization of anthocyanins, carotenoids, DM, and ash contents of the eighteen cultivars, these parameters were visualized according to a heatmap colour representation (Figure 3). The hierarchical clustering (dendrogram) and heat mapping evidenced the presence of three main groups (clusters). The first is represented by DM, indistinctively clustered in this group. The second group is instead represented by carotenoids, and the third group by anthocyanins.

Dendrogram of the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) loadings plot of the different varieties of sweet potato.

In this study, our findings showed significant differences among the different varieties of sweet potato grown in Jamaica. The results showed that some cultivars were characterized by high contents of carotenoids and anthocyanins, while in some others the contents were low or not detected. Among our tested cultivars, OFSP was shown to be of better nutritional quality, and our findings demonstrated the higher level of carotenoid content in orange-fleshed cultivars compared to other tested sweet potato cultivars, purple-, yellow-, and white-fleshed ones, while anthocyanin level was higher in purple-fleshed cultivars compared to the other investigated cultivars.

Extensive literature reports the carotenoid content of sweet potato, which varies widely, depending on the cultivar, growing conditions, maturity, and storage conditions [17]. Ellong et al. [18] compared the composition of eight cultivars of sweet potato and found that β-carotene content varied from < 0.01 to 3.66 μg/g, while no trace of β-carotene was detected in two cultivars. Later, Zhao et al. [7] compared 86 sweet potato accessions, comprising white, yellow, orange, and purple flesh-coloured cultivars. The results showed a large variation of carotenoid content ranging from 0 to 133 μg/g DW with an average of 10.5 ± 21.8, and a coefficient of variation of 207%, thus demonstrating the large variation of carotenoid content in sweet potato cultivars. Similar results were reported by Mello et al. [19] on sweet potato grown in different locations. The orange flesh sweet potato (OFSW) Beauregard cultivar is well known for its high content of carotenoids, and in a study conducted by Gichuhi et al. [20], a content of 178 ± 28.5 μg/g DW was determined, and these results are in agreement with our findings. In another study, Hapke et al. [21] compared the carotenoid content of three OGSP cultivars, including Beauregard, and their results showed a content ranging from 1,203 to 1,320 μg/g DW in the three investigated cultivars, and the Beauregard cultivar averaged 1,230 μg/g DW of carotenoids.

Most known sweet potato cultivars have white or yellow flesh; however, some others have orange flesh containing a higher level of carotenoids or purple flesh containing a high level of anthocyanins. Ji et al. [22] assessed the anthocyanin content of four sweet potato cultivars and found a content ranging from 1.32 to 6.23 μg/g DW, while they did not detect anthocyanins in one variety. In an interesting study, Su et al. [23] compared three different sweet potato cultivars: white, orange (Beauregard), and purple. No anthocyanins were detected in the roots of the orange and white varieties, while in the purple variety, anthocyanins ranged from 0.053 to 5.67 μg/g DW, and these results are in agreement with our findings, where no anthocyanins were detected in Beauregard, Ms Mac, and Cock up cultivars.

On the other hand, anthocyanin pigments of purple sweet potato were identified by some studies. Chemically, peonidin and cyanidin were found to be the major anthocyanins with caffeic acid, ferulic acid, and coumaric acid as the main acyl groups [24–26]. In their study, Terahara et al. [27] identified six diacetylated anthocyanins in purple sweet potato, and Li et al. [28] identified thirteen different anthocyanins in different varieties of purple sweet potato.

According to Nair et al. [29], sweet potato produces the highest root DM content for human consumption, and Mbwaga et al. [30] indicated that high DM content is a trait of a good sweet potato cultivar. This was also reported by Kathabwalika et al. [31], who claimed that high DM content is indicative of mealiness in boiled or roasted sweet potato, and this property is preferred by consumers. Furthermore, DM is considered a major factor determining the performance of industrial roots as it is directly related to the products derived from sweet potato [32]. It should be noted that all cultivars except the Okinawa Purple cultivar had a DM content over 30%, and these cultivars can be recommended for consumption and processing. On the other hand, the Watson cultivar would be most popular among consumers and have major potential in the food processing industry in the production of value-added products from sweet potato. Oboh et al. [33] analysed DM content of forty-nine (49) different cultivars of sweet potato and found DM ranging from 17.82 to 36.36% with an average of 28.54%, and Ji et al. [22] reported a DM of four cultivars of sweet potato ranging from 27.5 to 32.6%.

Ash content of sweet potato varies widely depending on cultivar and other agronomic factors. Ash content is also a good factor in determining the mineral profile in food and can determine the physiochemical properties in food [34]. Ravindran et al. [35] assessed the ash content of sixteen varieties of sweet potato cultivars grown in Sri Lanka and found a yield ranging between 2.35% and 4.19%, with an average of 2.85%. Rosero et al. [6] reported much higher values of ash content, ranging from 3.7% to 5.5%, with a group’s average of 4.3%. Similar results but lower values of DM ranging from 1.68% to 3.21% have been reported by Ji et al. [22], while Gichuhi et al. [20] reported much lower ash contents ranging from 0.91% to 1.37%.

Conclusively, in this study, an attempt was made to segregate eighteen varieties of sweet potato grown in Jamaica based on carotenoids, anthocyanins, DM, and ash contents. Four varieties showed carotenoid content higher than 10 μg/g FW, nine varieties showed anthocyanin content higher than 500 μg/g FW, and the highest carotenoid and anthocyanin content were found in Beauregard and Okinawa purple, respectively. Statistically, the PCA revealed two principal components, which cumulatively ranged from 74% and 79.6%, while the HCA evidenced the presence of three main groups, namely anthocyanins, carotenoids, and ash. The results of the current study provided a better understanding of the nutritional quality of the different cultivars of sweet potato grown in Jamaica, and the data can be recognized and used integrally to improve the diet and enhance some agro-processed foods. Therefore, from these findings, which showed a marked difference in carotenoid and anthocyanin contents of the numerous cultivars of sweet potato grown in Jamaica, we can recommend some cultivars of sweet potato that could contribute significantly to improving local human nutrition by developing new products such as snacks or baked products with enhanced nutritional value.

DM: dry matter

FW: fresh weight

HCA: hierarchical cluster analysis

OFSP: Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato

PCA: principal component analysis

The authors thank BODLES for supplying sweet potato cultivars and the Food Laboratory technician for technical assistance.

KT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. NB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All the authors have read the manuscript and agreed with its content and its submission under its present form.

Noureddine Benkeblia, who is the Editorial Board Member of Exploration of Foods and Foodomics, declares not to be involved in any way in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

All data on the findings of this study are available within this paper.

This research was partly supported by BODLES Research Station, MOAFM, Jamaica, and partly by the OGSR, UWI Mona. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 534

Download: 54

Times Cited: 0