Affiliation:

1Institute of Molecular Pathobiochemistry, Experimental Gene Therapy and Clinical Chemistry (IFMPEGKC), RWTH University Hospital Aachen, D-52074 Aachen, Germany

†

Email: rweiskirchen@ukaachen.de

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3888-0931

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Modena, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara (–2023), 41100 Modena, Italy

†

Email: a.lonardo@libero.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-0698

Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2026;3:101458 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eemd.2026.101458

Received: November 30, 2025 Accepted: January 21, 2026 Published: February 02, 2026

Academic Editor: Sunil J. Wimalawansa, Cardio-Metabolic & Endocrine Institute, USA

This commentary discusses a recent article (J Diabetes 2025;17(3):e70063), focusing on interpreting the study’s sex-stratified results in a broader clinical and mechanistic context. The authors of this systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials demonstrate that women achieve greater weight loss induced by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists compared to men (mean difference of 1.04 kg or 1.69%). Analyses specific to different drugs consistently show that women benefit more from dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and retatrutide, with trials focused on obesity further emphasizing this gap. Sensitivity analyses confirm the reliability of these findings and indicate the absence of publication bias. We discuss the clinical implications of these results, suggesting that healthcare providers should consider sex differences when counseling, monitoring, and dosing patients. We also advocate for future trials that are adequately powered and stratified by sex to evaluate factors such as adherence, adverse events, and body composition. Mechanistic hypotheses, such as sex-related pharmacokinetics, estrogen-GLP-1 synergy, and varying inflammatory responses, should be investigated further to inform precision dosing. Lastly, we recommend that regulatory agencies revisit current labeling, which claims no sex differences, as more sex-stratified evidence becomes available. It is important to acknowledge the existing heterogeneity and remaining uncertainties in this area of research.

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing, multifactorial disorder defined by the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue (AT), presenting considerable challenges to individual health and public health systems globally [1]. While a clinically and epidemiologically utilizable metric, body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, is non-specific, it fails to define the multiple genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors involved in obesity and introduces ethnicity-specific definitions of obesity [1, 2]. Recently, a Lancet Commission introduced a definition of obesity that incorporates body mass with anthropometric measurements, representing a significant advancement in the conceptualization and classification of obesity [3]. The commission introduces a fundamental distinction between clinical obesity, defined by the presence of adverse health consequences attributable to excess body fat, and preclinical obesity, in which excess fat mass is present but functional impairment is not yet clearly manifest [3]. This paradigm shift from a purely BMI-centric definition to a functional and risk-based framework affects the interpretation of sex differences. Women and men with similar BMI or weight loss may differ in functional outcomes, including cardiometabolic risk, liver disease, sleep apnea, and reproductive health. This underscores the need for sex-stratified evaluation of clinical endpoints beyond weight alone. Adoption of this revised obesity definition leads to a significant increase in reported obesity prevalence, especially among older adults. This change may have important public health and financial impacts, supporting the integration of anthropometric-only obesity into the new definition and emphasizing the importance of clinical obesity in identifying individuals most at risk for adverse health outcomes [4].

The global health burden associated with elevated BMI has increased substantially from 1990 to 2021, owing to genetic predisposition, urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and increased consumption of junk foods, affecting life expectancy and quality of life [1, 5]. Furthermore, the rising prevalence of obesity contributes to increased healthcare costs and diminishes workforce productivity, thereby placing significant pressure on healthcare systems globally [6]. With this background, our commentary focuses on a recently published article [7]. Our primary goal is to interpret and discuss the sex-stratified findings from this study in a broader clinical and mechanistic context. To achieve this, we first discuss sex differences in obesity. Next, we critically analyze the methods, findings, and interpretation of this study. Finally, we address clinical implications and research perspectives before concluding.

Sex influences body composition, fat distribution, neuroendocrine regulation of appetite, and pharmacokinetics. Android obesity (typically associated with the expansion of visceral AT) differs from gynoid obesity (which has a gluteo-femoral distribution of AT) in terms of increased cardiovascular risk and metabolic dysfunction [8]. These sex differences can impact both baseline weight and responses to lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions [9]. Therefore, in addition to BMI, other clinically actionable metrics should also be used in studies on obesity. These include waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), which have been found useful in identifying categories of increasing severity of obesity [10]. Importantly, while WC has ethnicity- and sex-specific cut-off values, WHR does not require any sex-specific cut points [10].

Among pharmacotherapies, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have proven effective for weight reduction and are increasingly used in managing obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [11]. However, the extent to which sex affects the magnitude of weight loss induced by GLP-1 RAs has been debated.

A detailed analysis of forty-seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has shown that the greatest treatment benefits can be obtained in young female patients without diabetes, with higher baseline weight and BMI but lower baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), who are treated over a longer duration [11, 12]. Data also showed that female sex is associated with a hyper-response to GLP-1 analogue therapy in obesity management [13]. However, other studies did not find any evidence for many qualitative sex differences in the therapeutic effect of clinically approved GLP-1 analogs [14, 15] or even found more significant improvements in weight loss in men [16].

Adding to the uncertainty, prescribing information for several GLP-1 RAs does not highlight any significant sex differences in weight-loss efficacy [14]. The conflicting evidence is due to variations in study populations, sample sizes, and the lack of sex-stratified reporting in trials. It remains unclear if sex differences are consistent across different agents, doses, treatment durations, baseline characteristics, and indications for obesity or T2D. With the increasing use of incretin-based therapies, understanding sex differences and their clinical relevance has become crucial for patient care, trial design, and personalized treatment.

To further address these gaps and discrepancies, Yang and colleagues [7] conducted a comprehensive analysis of RCTs to determine if there are differences in GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss between females and males, and to identify potential factors that may influence any observed disparities.

The authors included 14 studies spanning dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and retatrutide. They complemented the core meta-analyses with meta-regression and prespecified subgroup analyses by dose, duration, indication, and background therapies. They also positioned their findings against drug labels and prior studies that largely report no sex differences in efficacy, thereby addressing an important gap with a systematic, quantitative approach [7].

The review adheres to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards and is registered with international PROSPERO (CRD42023480167), enhancing transparency and rigor [17, 18]. It restricts inclusion to RCTs longer than 12 weeks in adults with and without T2D, provided that sex-specific weight change is reported. The meta-analytic review applies inverse-variance random-effects models to estimate the pooled mean difference (MD). Outcomes are assessed both as absolute kilogram change and percent change from baseline, with heterogeneity tested using I-squared heterogeneity statistics (I2) and Cochran’s Q. A meta-regression links the magnitude of overall weight loss to the size of sex differences. Across trials, the mean age was 55.3 years, the mean BMI was 32.8 kg/m2, the baseline weight was 91.81 kg, and women constituted 37–66.7% of participants, providing a broad adult population with overweight or obesity.

The authors extracted detailed trial-level data, including sample sizes by sex, age, BMI, baseline weight, duration, agents and dosing, indication, comparators, and background therapy. They assessed the risk of bias with the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool 2 (RoB 2), which provides a structured, transparent framework to evaluate threats to validity in RCTs from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and reporting [19]. The authors combined multiple doses of the same GLP-1 RA within trials according to Cochrane guidance, pooled by drug and across drugs to estimate sex differences, and used sensitivity analyses to test robustness in the presence of high-effect studies (e.g., retatrutide). Potential publication bias was evaluated with Egger’s test and funnel plots that further help provide information about the likely presence, or apparent absence, of selection bias and other biases [20].

Data indicate that women lost more weight than men by a pooled MD of 1.04 kg (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.70–1.38; p < 0.01), and by 1.69% when expressed as a percentage of baseline weight (95% CI 0.78–2.61; p < 0.01). Drug-specific analyses showed significant sex differences favoring women for dulaglutide (MD 0.88 kg), liraglutide (MD 1.30 kg), semaglutide (MD 1.04 kg), and retatrutide (MD 4.21 kg), with exenatide showing no significant sex difference (MD 0.75 kg; p = 0.25). Meta-regression revealed a strong relationship between the magnitude of overall weight loss and the size of the sex difference with β = –0.19 (95% CI –0.29 to –0.09; p < 0.01), indicating larger female-male differences in contexts of greater absolute weight loss. Trials conducted for obesity indications exhibited larger sex differences than diabetes indications (MD 4.21 kg vs. MD 0.99 kg; p for subgroup difference < 0.01), consistent with the scaling of sex effects alongside total weight loss achieved. Dose, background treatment, treatment duration, baseline weight, and control type did not yield statistically significant subgroup differences in the sex effect, although numerically larger sex differences tended to accompany regimens and contexts with greater overall weight reduction. Sensitivity analyses excluding the high effect retatrutide study preserved the core signal (MD 0.99 kg), and pooled analyses excluding retatrutide remained significant (MD 0.85 kg), with no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s p = 0.09).

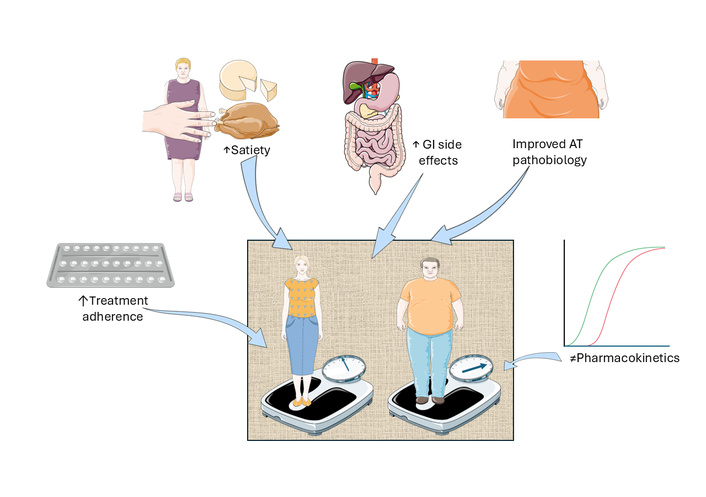

The central message is that women undergoing GLP-1 RA therapy tend to lose slightly more weight than men. This difference in weight loss is said to increase with the potency of the treatment and the amount of weight loss. This finding is clinically plausible and aligns with the hypotheses put forth by the authors. They suggest that this difference could be due to factors such as sex-based pharmacokinetics (with women having higher exposure due to lower body weight and lower clearance), potential synergy between estrogen and GLP-1 in central circuits that regulate food reward and satiety, greater improvements in inflammatory and adipokine markers in women, a higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects that may temporarily reduce energy intake, and potentially better adherence among women. These mechanisms are illustrated schematically in Figure 1 and, more analytically, in Table 1.

Mechanisms of sex and gender differences in glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) response. Graphical overview of the putative determinants leading to different responses in women and men to GLP-1 RA treatment for obesity. AT: adipose tissue; GI: gastrointestinal. This original illustration is provided by Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/) and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

| Putative mechanism | Direction of the expected sex difference | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetics | Differences in body weight, body composition, and drug clearance are expected to result in higher GLP-1 RA drug bioavailability in women at the same nominal dose. This sex difference would result in greater body weight reduction in females than in males. | [21] |

| Hormonal | Estrogen and GLP-1 RAs may synergistically activate the supramammillary nucleus, altering food-reward behavior via pro-opiomelanocortin neurons and leading to greater weight loss in females. | [22] |

| Adipose tissue biology | Combining GLP-1 RAs with estrogen may improve leptin resistance, C-reactive protein, and TNF-α, which may contribute to the more substantial weight reduction in females than in males. | [22, 23] |

| Adverse event profile | A higher GLP-1 RA incidence of gastrointestinal adverse reactions in females compared to males could contribute to reduced energy intake. | [24] |

| Adherence/behavioral factors | Owing to socio-cultural reasons, women exhibit more stringent adherence to GLP-1 RAs than men. | [25] |

GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist.

The analysis also acknowledges previous research showing no sex differences in glycemic control or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) with GLP-1 RAs. This suggests that the differences in weight loss may be driven by mechanisms separate from glucose and cardiovascular outcomes, or that larger and longer studies may be needed to see these effects translate into those areas. However, caution should be exercised in the interpretation of these findings, given that Yang et al.’s meta-analysis fails to report changes in WHR or WC. This lack of body-fat distribution data constitutes an important limitation when interpreting the apparent advantage of women in terms of absolute or percentage weight loss. It is therefore recommended that further research be conducted to address this important research question.

The study has substantial clinical implications. Clinicians should inform patients that women may experience slightly greater absolute and relative weight loss with GLP-1 RAs than men. This difference becomes apparent as treatment regimens result in larger overall reductions, while still emphasizing that both sexes benefit significantly. The observation that obesity-indication trials demonstrate larger sex differences highlights the importance of patient selection and baseline characteristics when interpreting outcomes and advising patients. Although formal dose-subgroup differences were not statistically significant, the trend of clearer sex differences with greater weight loss suggests the need for sex-specific interpretation of response trajectories during dose escalation, particularly for semaglutide and newer multi-agonists. Moreover, the findings of this review showing no consistent sex differences in glycemic control or MACE with GLP-1 RAs warn against assuming uniform sex effects across all endpoints and encourage future sex-stratified cardiometabolic analyses in trials that achieve substantial weight loss.

Based on these findings, future GLP-1 RA studies should prospectively stratify and report outcomes by sex. They should also plan interaction analyses, including adherence, adverse events, lifestyle changes, and body composition, to move beyond reliance on post hoc or pooled datasets. Given the observed scaling of sex differences with total weight loss, obesity-focused trials and dose-ranging studies should be powered to detect sex-by-treatment interactions. They should also consider moderators such as age, menopausal status, and baseline adiposity in their statistical analysis plans. Comparing the findings of this study with current drug labels that state no sex differences highlights the need for ongoing evidence synthesis to inform guideline and labeling updates as more sex-stratified data become available.

Historically, the number of trials with sex-stratified or race reporting remains limited or unbalanced [26]. Some analyses are post hoc, and several studies only provide pooled data rather than trial-level sex-specific results, which increases the risk of bias and constrains granularity. Available data predominantly reflect absolute kilogram changes rather than percent changes, limiting assessment of relative effects against initial body weight [27]. Potential confounding factors, such as adherence, gastrointestinal adverse reactions, lifestyle modifications, mental health, and baseline BMI differences by sex, were not consistently available, which may attenuate or inflate observed differences [28]. The absence of a significant sex disparity in the exenatide subgroup cautions against overgeneralization across the entire drug class and underscores agent-specific variability [12, 14]. Although publication bias was not detected, the scarcity of sex-stratified reporting for many agents, including newer oral and multi-agonists, means the evidence base is still incomplete, and conclusions should be applied thoughtfully. In this context, it should be noted that the advent of new highly effective anti-obesity medications has brought pharmacotherapy of obesity into the mainstream, and prescription rates are increasing rapidly because patients are increasingly asking their physicians for respective drugs [29]. Additionally, there are two intertwined elements of variability contributing to the complexity in therapy. Firstly, the pathogenesis of obesity-associated diseases such as metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or liver fibrosis, themselves depend on or are influenced by sex and gender differences [30, 31]. Secondly, recent evidence suggests that GLP-1 RAs in close connection with its promotion of weight loss, may also have a key role in the therapy of obesity- and overweight-related functional male hypogonadism [32].

Guidelines produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society (AHA/ACC/TOS) [33], and the Endocrine Society [34] recommend a goal of ≥ 5% weight loss. However, evidence indicates that achieving a weight loss of 10% or more results in significantly greater and clinically relevant improvements in weight-related comorbidities such as cardiovascular events, improvement in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) histology, decreased disease activity among patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases, as well as enhanced outcomes in osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and reduced cancer risk [35]. Importantly, it is essential that clinical decision-making considers both the average differences between sexes and the percentage of individuals achieving clinically significant weight-loss benchmarks. The lack of harmonized responder data in the Yang and colleagues’ meta-analysis represents a limitation that should be addressed in future trials and meta-analyses. Finally, it should be emphasized that “greater” treatment effectiveness in women based on weight loss alone should not be equated uncritically with greater reduction in cardiometabolic risk. Men, who often have more visceral (android) adiposity, may derive substantial metabolic benefit from more modest absolute weight loss if it preferentially reduces metabolically active abdominal fat depots.

Future research should elucidate the mechanisms underlying the sex difference in GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss and carefully report sex-specific variations in weight and other outcomes to more effectively evaluate the impact of sex on diverse health endpoints. To foster these goals, the field should incorporate sex hormone profiling, central appetite circuitry measures, and leptin sensitivity into mechanistic studies. Additionally, it requires developing sex-aware quantitative, mechanistic, or semi-mechanistic models that link how much drug gets into the body over time, allowing for predicted exposure-response relationships, variability between people, and the impact of covariates like sex, body weight, and renal function. This will expand outcome assessments to include MASLD, blood pressure, lipid profiles, sleep apnea, sexual function, and quality of life in a sex-specific manner over longer follow-ups.

Significant variability exists in GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss among both women and men, with individual outcomes likely influenced by a combination of genetic factors, such as polymorphisms in the GLP-1 receptor and related signaling pathways [36], baseline eating behaviors [37], levels of physical activity [38], microbiome profiles [39], and psychosocial determinants [40]. Additional investigation should aim to integrate pharmacogenetic, behavioral, and environmental covariates. To this end, quantitative, mechanistic, or semi-mechanistic exposure–response models should be leveraged to develop sex-specific prediction models of responders to GLP-1 RA therapy.

OSA and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are examples of clinically important, sex- and gender-related endpoints that should be evaluated prospectively in future GLP-1 RA trials. Recent research indicates that weight loss achieved using GLP-1 RAs improves the severity of OSA. This effect has been observed with pharmacological intervention alone, as well as in conjunction with conventional positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. GLP-1 RAs may exert beneficial effects on OSA by reducing systemic inflammation and adiposity, potentially mediated by hormonal modulation, delayed gastric emptying, and central mechanisms that influence appetite regulation and the sleep-wake cycle [41]. GLP-1 RAs may offer therapeutic benefits for individuals with PCOS by improving endocrine-metabolic dysfunction via weight management, increased insulin sensitivity, and decreased hyperandrogenism [42].

The meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues provides compelling evidence that, on average, women experience more significant weight loss from GLP-1 RA treatment compared to men. This disparity in weight loss between sexes becomes more apparent as treatments lead to greater overall weight reduction, especially in trials focused on obesity. The findings of the study are biologically plausible, clinically relevant, and methodologically sound, although mechanistic insight remains poorly defined. However, irrespective of underlying pathomechanisms involved, these data support the importance of incorporating sex-stratified design, analysis, and reporting as the standard in future GLP-1 RA trials. Investigating the underlying mechanisms of sex differences in drug efficacy can lead to more precise and personalized care for individuals with obesity and diabetes. Future trials should incorporate the Lancet Commission framework by stratifying and analyzing clinical obesity endpoints (e.g., MASLD, MACE, OSA, quality of life) by sex, instead of relying solely on anthropometric changes.

AT: adipose tissue

BMI: body mass index

CI: confidence interval

GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events

MASLD: metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

MD: mean difference

OSA: obstructive sleep apnea

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

T2D: type 2 diabetes

WC: waist circumference

WHR: waist-to-hip ratio

Figure 1 was generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier. During the preparation of this work, the authors used the freely available AI Editing software “Edit My English” and “Copilot” to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. However, after using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed; therefore, they take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

RW: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. AL: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Amedeo Lonardo, who is the Editorial Board Member of Exploration of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other author declares no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 538

Download: 17

Times Cited: 0