Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0186, Georgia

2ClinNova International, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia

Email: islam1048@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4855-6226

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0186, Georgia

2ClinNova International, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6061-3537

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0186, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4652-4148

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0186, Georgia

2ClinNova International, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2943-6404

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101295 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101295

Received: December 22, 2025 Accepted: January 28, 2026 Published: February 12, 2026

Academic Editor: Alireza Ansari-Moghaddam, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine–metabolic condition that carries a higher cardiovascular risk than currently reflected by traditional screening tools. Emerging evidence suggests that resting tachycardia and autonomic dysfunction may serve as early, non-invasive indicators of cardiovascular dysregulation in this population. This review synthesizes current data on resting heart rate (RHR), heart rate variability (HRV), and direct autonomic markers in women with PCOS, drawing from human studies published between 2000 and 2025. Across 32 eligible studies, most reported increased sympathetic activity, reduced parasympathetic tone, elevated RHR, and impaired HRV patterns observed even in normal-weight or metabolically mild PCOS phenotypes. These alterations correlate with endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and subclinical atherosclerosis, underscoring their cardiovascular relevance. Mechanistic insights highlight the contributions of insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, inflammation, adipokine imbalance, chemoreflex sensitization, and altered cortisol metabolism to autonomic disruption. Despite consistent findings, methodological variability in HRV protocols and inadequate adjustment for major confounders limit definitive interpretation. RHR, due to its simplicity and accessibility, including through wearable devices, holds promise as a supportive early risk signal; however, it should not be used in isolation. Future studies must adopt standardized autonomic measurements, including diverse cohorts, and evaluate whether modifying autonomic markers translates into improved cardiometabolic outcomes. Integrating RHR and HRV with metabolic and endocrine markers may enhance early cardiovascular risk stratification in women with PCOS.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder in women during their reproductive age. It is characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, insulin resistance, and neuroendocrine disruption. Depending on the diagnostic criterion used, it may be present in up to 6% to 10% of the world’s population. The prevalence may increase to 18% if the broader Rotterdam criteria are applied, which include polycystic ovarian morphology, hyperandrogenism, and ovulatory dysfunction [1, 2]. PCOS prevalence is also noted to vary based on ethnicity, geographical location, and lifestyle, with South Asian and Middle Eastern ethnic groups having increased prevalence rates [2].

PCOS is associated with metabolic features that predispose to atherosclerosis. Women with PCOS show early vascular changes like carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and endothelial dysfunction. The finding of such early abnormalities on a consistent basis emphasizes the importance of cardiovascular screening in PCOS as part of long-term risk management [2, 3].

Given that most women with PCOS are young and do not show obvious signs of cardiovascular disease, the early detection of vascular dysfunction is crucial. Traditional cardiovascular risk tools may underestimate the risk in women with PCOS as they rely on age and typical risk factors. Given the higher background prevalence of insulin resistance, obesity, and genetic predisposition to metabolic syndrome among Middle Eastern and South Asian populations, the cardiovascular and metabolic burden of PCOS in these ethnic groups appears to be more pronounced. Research from Turkey, Iraq, and Iran has shown that women with PCOS have considerably lower heart rate variability (HRV) and higher resting heart rate (RHR) than age- and body mass index (BMI)-matched controls, suggesting an increased sympathetic drive unrelated to obesity [2]. Therefore, it is recommended to use early, non-invasive markers such as flow-mediated dilation (FMD), coronary artery calcium scoring, and carotid intima-media thickening to detect pathological vascular changes before overt disease develops. These early signs can often be improved with lifestyle changes, weight loss, and medications that improve insulin sensitivity. Recognizing cardiovascular risk early in women with PCOS provides an opportunity to prevent future cardiovascular diseases. In this light, exploring other early markers like autonomic dysfunction or RHR could enhance the ability to identify at-risk individuals and act in a timely manner [3].

Recent data point towards autonomic dysfunction as a contributor to the early cardiovascular disturbances in women with PCOS [4]. Resting tachycardia, or an increased RHR, is a simpler, non-invasive clinical parameter that can also reflect underlying autonomic imbalance and cardiovascular risk. Since RHR is affected by sympathetic-parasympathetic tone, metabolic status, and systemic inflammation, all of which are altered in PCOS, it could be a useful early warning sign for cardiovascular diseases [1]. Resting tachycardia’s ease of measurement makes it a practical early screening tool.

The aim of this review is to evaluate resting tachycardia and autonomic imbalance as emerging early cardiovascular markers in PCOS. The learning objectives are to: (1) summarize current evidence on RHR abnormalities in PCOS; (2) explain their mechanistic links with inflammatory, metabolic, and endocrine disturbances; (3) compare their clinical relevance to established indicators such as HRV and heart rate recovery; and (4) outline potential implications for early cardiovascular risk stratification. This focused review included human observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort designs) published between January 2005 and March 2025 that evaluated RHR, HRV, or direct autonomic measures in women with PCOS diagnosed using recognized criteria (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Rotterdam, or Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Criteria). Studies enrolling adult or adolescent females with age- and/or BMI-matched control groups were prioritized. Exclusion criteria included animal studies, interventional trials without baseline autonomic data, studies lacking a non-PCOS comparator group, abstracts without full-text availability, case reports, and studies in which heart rate measures were confounded by pregnancy, overt cardiovascular disease, thyroid dysfunction, or chronic arrhythmias.

This review also responds to an existing gap in the literature. Prior studies have focused predominantly on metabolic and vascular abnormalities in PCOS, while RHR and autonomic dysfunction, despite their feasibility and potential clinical utility, remain underexamined and fragmented across small, heterogeneous studies. By synthesizing this evidence, the review consolidates a topic that has not previously been evaluated in a focused cardiovascular context.

PCOS has a complex pathophysiology that includes increased pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, high testosterone levels, insulin resistance, obesity, chronic low-grade inflammation, and decreased gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility. Additionally, in PCOS individuals, these variables subsequently lead to coronary artery calcification, increased carotid artery intima-media thickness, and endothelial dysfunction [5]. Insulin resistance, present in up to 95% of women with PCOS, leads to hyperinsulinemia, dysglycemia, and metabolic syndrome, all of which increase cardiovascular risk. Obesity, affecting 40–80% of patients, further worsens insulin resistance, promotes inflammation, stimulates androgen production, and disrupts glucose and lipid metabolism [6].

Furthermore, this metabolic dysfunction is maintained by hyperandrogenism, and high testosterone levels worsen insulin resistance, promote the formation of visceral fat, and directly affect vascular function through inflammation and oxidative stress. Elevated biomarkers like C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α, IL-6, and homocysteine in PCOS are indicative of chronic low-grade inflammation, creating a pro-atherogenic environment that compromises endothelial integrity and hastens vascular aging [4].

In addition, there is growing evidence for substantial autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction in women with PCOS. A meta-analysis indicates increased sympathetic tone, reflected by an elevated low frequency/high frequency (LF/HF) ratio and increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), together with altered HRV characterized predominantly by reduced parasympathetic modulation (lower standard deviation of NN intervals [SDNN], percentage of NN intervals greater than 50 milliseconds [pNN50], and HF normalized units [HFnu]). This pattern of sympatho-vagal imbalance is clinically relevant, as it increases the risk of hypertension and arrhythmia. Women with classic PCOS characteristics exhibit persistent sympatho-vagal imbalance, elevated blood pressure responses to stress, and reduced parasympathetic reactivity, according to clinical research [7].

A RHR of more than 100 beats per minute (bpm) is known as resting tachycardia. This condition is clinically significant because it frequently indicates underlying ANS dysfunction and has been linked to increased risks of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This tachycardia in women with PCOS is caused by an abnormal autonomic state characterized by sympathetic hyperactivity, reduced parasympathetic (vagal) tone, and observable changes in HRV [8, 9]. Moreover, adolescents with PCOS have been shown to exhibit a significantly higher RHR compared with matched controls, indicating chronic autonomic imbalance; for example, in a study performed in Poland, PCOS participants had higher nocturnal RHR than controls [10]. As mentioned earlier, insulin resistance contributes to sympathetic overactivity. Thus, chronic basal tachycardia is common in women with PCOS, even when there is no overt cardiovascular disease. It is important to acknowledge that RHR is a non-specific marker influenced by multiple physiological and behavioral variables, including physical fitness, thyroid status, psychological stress, circadian rhythms, stimulant use (caffeine, nicotine), and medications such as beta-blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or oral contraceptives. Few PCOS studies comprehensively adjusted for these factors, which limits the interpretability of RHR as an isolated cardiovascular signal [7]. Thus, RHR should be considered supportive rather than definitive, and best interpreted alongside metabolic, endocrine, and HRV parameters.

The sympathetic nervous system (also known as the “fight-or-flight”) is frequently overactive in women with PCOS due to insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and other metabolic disruptions, as explored in later sections. Insulin resistance and elevated insulin levels increase the production of ovarian androgens and decrease sex hormone-binding globulin, which raises free androgens [11, 12]. These hormones also impair insulin sensitivity and increase sympathetic drive through both central and peripheral pathways. Adipose tissue malfunction contributes to this imbalance through oxidative stress and adipokine signaling. The autonomic balance shifts toward prolonged sympathetic dominance and decreased parasympathetic (vagal) restraint by these combined metabolic and hormonal insults, which paves the way for resting tachycardia and compromised cardiovascular regulation in PCOS [12, 13].

HRV, as discussed earlier, reflects autonomic regulation of the heart. Higher HRV is indicative of healthy autonomic balance, whereas lower HRV usually denotes decreased parasympathetic activity and elevated sympathetic tone [14]. Numerous studies on PCOS women, including those with normal weight and good glucose control, consistently reveal abnormalities in HRV: they have lower HF activity and HFnu, which reflect low parasympathetic tone, and higher LF components and LF/HF ratio, which both indicate sympathetic overactivity [7, 11, 14]. These disparities between PCOS and controls, irrespective of BMI or metabolic status, were further supported by a recent meta-analysis [7].

Reduced HRV and resting tachycardia in PCOS are not just diagnostic indicators; they are significant autonomic dysregulation that could result in long-term cardiovascular effects. A faster-than-normal RHR is linked to an increased risk of hypertension, arrhythmias, and early vascular aging, whereas a lower HRV indicates diminished cardiac resilience and flexibility [13, 14]. Meta-analyses confirm these findings with consistent reductions in HRV and an increase in sympathetic markers among PCOS patients, including those with normal BMI [7].

Through a variety of mechanisms, such as its detrimental effects on the development of coronary atherosclerosis, the incidence of myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias, on left ventricular function, and on circulating levels of inflammatory markers, an elevated heart rate has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Elevated RHR in early cardiovascular failure, especially in diseases like PCOS, is believed to be a sign of an underlying autonomic imbalance, which is typified by decreased vagal tone and increased sympathetic activity [15]. The association between PCOS and cardiometabolic disorders is well established, with metabolic syndrome being notably more prevalent in women with PCOS, especially those who are overweight or obese [16]. Androgen excess, the hallmark of PCOS, as mentioned earlier, is related to deleterious cardiometabolic consequences, with evidence suggesting that hypo- and hyperandrogenic states may elevate cardiovascular risk [17]. Insulin resistance, another key feature of PCOS, intrinsically reduces insulin sensitivity by about 27% regardless of BMI [18]. Its interaction with hyperandrogenism not only drives clinical features of PCOS but also heightens the risk of long-term complications such as endometrial cancer and cardiovascular disease [19]. South Asian women show the highest prevalence of diagnosed PCOS at 3.5%, compared to 1.6% in white women [20]. Hispanic women exhibit the most severe PCOS phenotype, with higher rates of metabolic syndrome and hyperandrogenism compared to non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Asian women [20, 21]. Non-Hispanic Black women, despite having a higher prevalence of some metabolic abnormalities, show a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome and milder overall PCOS phenotype compared to Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women [21]. These disparities are attributed to interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors [22]. Studies have found increased CIMT in PCOS patients compared to controls, independent of obesity [23]. Endothelial dysfunction, assessed by FMD, is also impaired in PCOS [24]. Additionally, PCOS patients show elevated arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV) and reduced FMD compared to weight-matched controls [25]. These cardiovascular risk markers are thereby associated with androgen excess, insulin resistance, and metabolic abnormalities commonly observed in PCOS [23]. Other markers, such as highly sensitive CRP (hs-CRP), show inconsistent results across studies [25]. Table 1 summarizes the key studies evaluating RHR and HRV in women with PCOS, highlighting consistent findings of autonomic imbalance despite heterogeneity in study designs.

Summary of key studies on RHR and HRV in women with PCOS.

| Author, year | Country | Sample (n) | PCOS phenotype | Main findings on RHR/HRV | Confounders considered | Measurement method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yildirir et al., 2006 [14] | Turkey | 30 PCOS vs. 30 controls | Mixed | Lower HRV (↓HF, ↑LF/HF), suggesting sympathetic overactivity | Age and BMI matched | 24-h Holter ECG |

| Hashim et al., 2015 [13] | Iraq | 64 PCOS vs. 40 controls | Rotterdam criteria | Reduced HRV parameters (↓SDNN, ↓rMSSD, ↓pNN50), indicating vagal withdrawal | Age and BMI matched | Resting ECG, time/frequency analysis |

| Di Domenico et al., 2013 [36] | Brazil | 46 PCOS | Rotterdam criteria | Sympathetic predominance in hyperandrogenic phenotype; blunted HRV reactivity during stress | Controlled for BMI, age | Tilt test + HRV analysis |

| Ji et al., 2018 [11] | Korea | 35 PCOS vs. 32 controls | Rotterdam criteria | Elevated LF, LF/HF; reduced HFnu → sympatho-vagal imbalance | Adjusted for BMI, metabolic profile | 5-min ECG HRV |

| Ollila et al., 2019 [34] | Finland (Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966) | 160 women (~46 years, 30 with PCOS) vs. 1029 controls | Self-reported + records | Lower vagal HRV indices (rMSSD, HF power) in PCOS, but attenuated after adjusting for metabolic factors | Adjusted for BMI, insulin, BP, lipids | Standardized short-term HRV |

| Sverrisdóttir et al., 2008 [30] | Sweden | 20 PCOS vs. 18 controls | Rotterdam criteria | Elevated MSNA; correlated with testosterone | BMI, age | Microneurography |

| Özkeçeci et al., 2016 [39] | Turkey | 23 PCOS vs. 25 controls | Mixed | Lower HRV + abnormal heart rate turbulence; indicates autonomic dysfunction | Excluded smokers, chronic disease | 24-h Holter ECG |

| Zachurzok-Buczynska et al., 2011 [10] | Poland | 34 PCOS vs. 17 controls (adolescent girls) | AES/AE-PCOS | PCOS participants, particularly those with obesity, exhibited higher mean 24-h and nocturnal heart rate compared with matched controls, alongside reduced parasympathetic HRV indices and increased sympathetic dominance | Age, BMI, blood pressure, insulin resistance, lipid profile | 24-h ambulatory ECG and blood pressure monitoring (Holter-based heart rate and HRV analysis) |

AES/AE-PCOS: Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society Criteria; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; ECG: electrocardiogram; HF: high frequency; HFnu: HF normalized units; HRV: heart rate variability; LF: low frequency; LFnu: LF normalized units; MSNA: muscle sympathetic nerve activity; NIH: National Institutes of Health; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; PNN50: percentage of NN intervals greater than 50 milliseconds; RHR: resting heart rate; rMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SDNN: standard deviation of NN intervals; →: leads to.

Monitoring RHR offers a clinically valuable and practical tool as it is simple, non-invasive, and cost-effective. Measuring RHR requires little equipment or staff training, making it particularly suitable for primary care and gynecology clinic settings, where routine screening and follow-up assessments are common. However, a conclusion is drawn from a study that heart rate monitoring as part of a primary care physician’s daily routine does not offer pertinent cardiovascular outcome predictive information [26]. This highlights the ongoing debate regarding the clinical interpretation and utility of isolated RHR values, particularly when not combined with other physiological or biochemical markers [26].

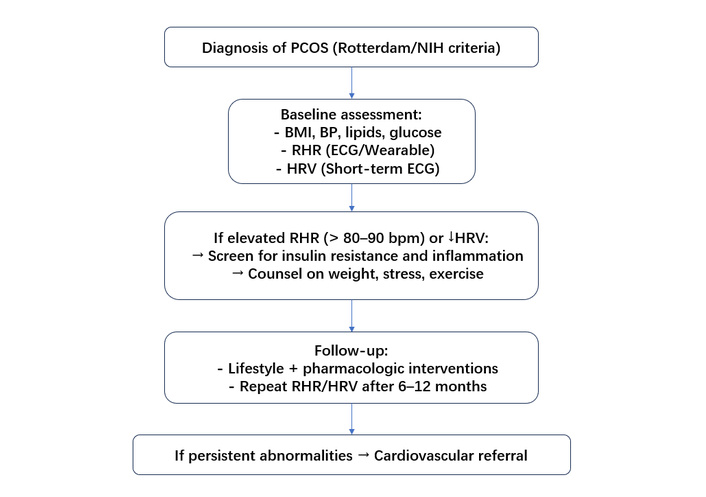

HRV and circadian rhythm patterns can be measured in real time using wearable and ambulatory devices, including wristbands and smartwatches, which enable continuous heart rate tracking. These parameters are not feasible through single clinic-based readings. A more complete picture of cardiovascular stress and autonomic function is provided by these devices. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that longitudinal wearable data correlates with cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes in sizable cohorts, which makes passive long-term monitoring easier, enhances patient engagement, and may even make it possible to identify cardiovascular risk early [27]. Recommended screening measures in such populations include regular lipid and glucose evaluations, CIMT assessments, and coronary artery calcium scoring, all of which contribute to cardiovascular risk stratification [28]. Traditional cardiovascular risk assessment tools such as the Framingham Risk Score, SCORE2, and ASCVD calculators rely heavily on age and established risk factors, leading to systematic underestimation of cardiovascular risk in young women with PCOS. In contrast, RHR and HRV capture early autonomic and inflammatory dysregulation that precedes overt metabolic or structural vascular disease. While RHR and HRV lack disease specificity, they offer complementary physiological insight and may enhance early risk stratification when integrated with metabolic markers rather than replacing established tools [29]. Importantly, both non-pharmacological strategies, like diet, exercise, weight loss, and pharmaceutical treatments such as metformin and statins, have been effective in reducing cardiovascular risks in PCOS patients. When used alongside continuous heart rate monitoring, these tactics may facilitate early identification and tailored treatment [3]. Refer to Figure 1 for a conceptual clinical pathway for early cardiovascular risk detection in PCOS.

Suggested clinical framework for incorporating resting heart rate and heart rate variability into early cardiovascular risk assessment in women with PCOS. BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; ECG: electrocardiogram; HRV: heart rate variability; NIH: National Institutes of Health; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; RHR: resting heart rate.

Women with PCOS show an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity that contributes to resting tachycardia through autonomic dysfunction. One study measuring MSNA found higher levels in women with PCOS compared to matched controls [30]. Testosterone and cholesterol were independently associated with MSNA, with testosterone showing a stronger effect [30]. This suggests that androgen excess plays an important role in sympathetic overactivation. Due to the positive correlation between MSNA and testosterone levels, sympathetic activation may serve as a good indicator of the severity of hormonal disruption. Resting tachycardia, brought on by elevated sympathetic tone, raises cardiovascular strain and may be a precursor to cardiometabolic risk.

Emerging evidence suggests that chemoreflex activation may contribute to sympathetic overdrive in PCOS. Chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and intermittent hypoxia, particularly in women with coexisting obesity or sleep-disordered breathing, can sensitize peripheral chemoreceptors and amplify sympathetic discharge. This inflammatory environment is well-established in PCOS, where elevated leukocytes, CRP, TNF-α, and cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1, IL-8, and IL-17 correlate with insulin resistance and cardiometabolic dysfunction. These pathways may collectively contribute to persistently heightened sympathetic tone even in metabolically mild PCOS phenotypes, representing an underexplored mechanism in autonomic dysregulation [31]. This inflammatory environment is further driven by local macrophages stimulated by high androgen levels and may reinforce the link between systemic inflammation and resting tachycardia via autonomic imbalance.

Pasquali and Gambineri [32] report notable changes in cortisol metabolism, especially in visceral adipose tissue, even if systemic cortisol levels in PCOS are within the normal range. This results from increased local conversion of cortisone to cortisol due to elevated 5α-reductase and 11β-HSD1 activity. These changes lead to insulin resistance, central fat accumulation, and inflammation, all of which are linked to cardiometabolic risk in PCOS. Insulin has the ability to stimulate 11β-HSD1 activity, which can start a vicious cycle that results in excess cortisol levels and inadequate metabolic control. This disrupted cortisol signaling may impair the body’s autonomic control, shift the balance toward sympathetic dominance, and raise the RHR. Continuous hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation, which is frequently brought on by long-term stress, can eventually exacerbate ANS imbalance and resting tachycardia [32].

Adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin influence the metabolic and autonomic characteristics of PCOS. Cardoso et al. [33] discovered that leptin levels increase and adiponectin levels decrease directly in relation to body fat, regardless of PCOS status. Although not specific to PCOS, these alterations affect autonomic dynamics and metabolic equilibrium. Leptin resistance associated with visceral obesity can enhance sympathetic activity and raise RHR. Reduced adiponectin levels can exacerbate metabolic and autonomic dysfunction because of its anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects [33].

Altered beta-adrenergic receptor sensitivity has also been proposed, driven by chronic hyperinsulinemia and androgen excess, leading to enhanced cardiac responsiveness to sympathetic stimuli. Baroreflex impairment, reported in small mechanistic studies, may hinder appropriate vagal counter-regulation of heart rate, reinforcing resting tachycardia. Together, these mechanisms provide a more comprehensive physiological framework linking PCOS to autonomic imbalance [32, 34].

A major limitation of the available evidence is that most studies assessing HRV and RHR in PCOS are small, cross-sectional, and underpowered to determine causality. HRV protocols vary significantly in recording duration, frequency-domain parameters, posture, and timing across menstrual cycles. Importantly, many studies do not sufficiently control for major cardiometabolic confounders, particularly obesity, insulin resistance, fitness level, smoking, and medication use (metformin, oral contraceptives, beta-blockers), which influence autonomic measures independently of PCOS. These methodological weaknesses reduce the ability to distinguish PCOS-specific autonomic dysfunction from metabolic or lifestyle-related effects. Therefore, while patterns of sympathetic predominance are consistent, the strength of conclusions must remain cautious [11, 20]. Future studies should stratify autonomic analyses according to PCOS phenotypes defined by the Rotterdam criteria. Hyperandrogenic phenotypes may exhibit greater sympathetic activation and reduced vagal tone, potentially carrying higher long-term cardiovascular risk than normo-androgenic variants. Phenotype-specific autonomic profiling may therefore refine prognostic stratification [35]. The assessment of RHR and HRV in PCOS is highly dependent on methodological standards and is sensitive to a variety of confounding factors [11, 20]. HRV can be assessed by short-term (5–10 min) electrocardiogram (ECG), 24-h Holter monitoring, or, more recently, wearable devices. However, the lack of established protocols, such as posture (supine vs. seated), time of day, and menstrual cycle phase, hinders cross-study comparisons. The 1996 Task Force standards remain the highest standard for HRV evaluation, yet adherence to these recommendations varies in PCOS research [1]. Additionally, wearable-derived heart rate measures are intriguing but must be validated against clinical ECG criteria [2].

Prospective research on autonomic dysfunction and resting tachycardia in PCOS have to shift away from cross-sectional snapshots and toward extensive longitudinal cohort studies that monitor women’s heart rates, HRV, metabolic markers, and cardiovascular outcomes over an extended period of time since age, BMI, ethnicity, and cardiorespiratory fitness all have a direct impact on RHR and HRV [34, 36–38]. The Northern Finland Birth Cohort study, for instance, indicated that women with PCOS around the age of 46 had lower vagal HRV (root mean square of successive differences [rMSSD], HF power); however, metabolic factors, rather than the PCOS diagnosis itself, were the better indicators of autonomic impairment [7, 34, 36, 37, 39]. This emphasizes the necessity of prospective research that covers the range of reproductive ages from younger to later. HRV parameters are analytically classified into time-domain and frequency-domain indices, with the LF/HF ratio representing a frequency-domain measure of sympatho-vagal balance. Table 2 summarizes key confounding variables that influence RHR and HRV outcomes in women with PCOS, along with common strategies for control or standardization across studies.

Clinical implications of resting heart rate and HRV in PCOS.

| Category | Parameter | Physiological meaning | Association with PCOS | Potential clinical utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHR | RHR (> 80–100 bpm) | Global marker of autonomic balance; reflects sympathetic predominance | Higher in PCOS, even in the absence of overt CVD | Simple, low-cost supportive screening marker |

| HRV—time domain | SDNN | Overall autonomic variability | Reduced in PCOS | Identifies reduced autonomic flexibility |

| rMSSD | Parasympathetic (vagal) activity | Reduced in PCOS | Early marker of vagal withdrawal | |

| pNN50 | Beat-to-beat vagal modulation | Reduced in PCOS | Sensitive parasympathetic index | |

| HRV—frequency domain | HF power/HFnu | Parasympathetic activity | Decrease in PCOS | Reflects vagal tone |

| LF power/LFnu | Mixed sympathetic–parasympathetic modulation | Increase in PCOS | Indicates sympathetic influence | |

| LF/HF ratio | Sympatho-vagal balance | Elevated in PCOS | Detects sympathetic dominance | |

| Direct Sympathetic Measure | MSNA | Peripheral sympathetic nerve activity | Increased, correlated with testosterone | Research-grade mechanistic insight |

| Ambulatory Metrics | Wearable-derived heart rate/HRV | Longitudinal autonomic trends | Limited but promising | Population-level screening & monitoring |

CVD: cardiovascular disease; HF: high frequency; HFnu: HF normalized units; HRV: heartrate variability; LF: low frequency; LFnu: LF normalized units; MSNA: muscle sympathetic nerve activity; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; PNN50: percentage of NN intervals greater than 50 milliseconds; RHR: resting heart rate; rMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SDNN: standard deviation of NN intervals.

Beyond conventional time- and frequency-domain HRV measures, future work should incorporate nonlinear metrics such as Poincaré plot indices (SD1/SD2), entropy-based measures, and fractal scaling, which may better capture autonomic complexity in PCOS. Emerging evidence links nonlinear HRV abnormalities with repolarization disturbances and cardiometabolic risk in this population [40]. Cohorts from a variety of ethnic backgrounds and ages must be included in these studies. Up until now, the majority of HRV research has been on young, homogeneous populations, frequently from Brazil, India, or Turkey [37]. There is currently a dearth of significant information in older, post-reproductive PCOS cohorts and non-White groups. To determine whether autonomic dysfunction trajectories vary by phenotype, race, or life stage, it is imperative to enroll women of all ages and ethnic origins.

Another important unsolved topic is whether therapies that lower RHR or improve HRV lead to better clinical results in PCOS [7, 34]. There are currently no interventional trials in PCOS that specifically target heart rate or HRV and monitor endpoints like blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and vascular stiffness, despite the fact that lifestyle interventions like exercise have been demonstrated to improve HRV in general populations, and autonomic function seems responsive to metabolic improvements.

In addition, it is yet unknown how to incorporate RHR into models that predict cardiovascular risk in women with PCOS [36, 37]. Although it is a recognized independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and death in general populations, elevated RHR has not yet been fully assessed as a prognostic indicator in risk scores tailored to PCOS. Future studies should examine whether using basic RHR measurements enhances this group's early risk categorization.

Furthermore, creating biomarker panels that incorporate metabolic markers (lipid profiles, inflammatory markers, and insulin resistance indices), RHR, and HRV metrics (such as SDNN, rMSSD, and LF/HF ratio) could improve risk prediction and customize treatment [37, 38]. Furthermore, cardiopulmonary coupling (CPC) analysis represents a promising frontier for autonomic research in PCOS. Derived from a single-lead ECG, CPC evaluates the interaction between heart rate and respiration, reflecting integrated autonomic regulation and sleep stability. Given the high prevalence of sleep disturbances, sympathetic overactivity, and metabolic dysregulation in PCOS, CPC may provide novel mechanistic and prognostic insights beyond traditional HRV metrics [41, 42].

All in all, future research must address these gaps through large-scale, longitudinal cohort studies that track autonomic parameters over time, ideally with age-stratified and ethnically diverse populations to account for phenotypic variability in PCOS. Standardized measurement techniques should be developed, such as cycle-phase control, validated ECG-based HRV analysis, and consistent reporting of time- and frequency-domain characteristics. Interventional trials are also required to assess whether targeted RHR decrease through exercise training, pharmaceutical therapy, or mixed lifestyle therapies leads to improvements in cardiometabolic outcomes. Including RHR and HRV in predictive risk models alongside metabolic markers (insulin resistance, lipid profiles, and inflammatory mediators) may improve early cardiovascular risk stratification in PCOS. Furthermore, multi-biomarker panels that combine autonomic indices with metabolic and endocrine markers should improve individual risk prediction and identify women who will benefit most from early intervention.

Resting tachycardia and autonomic dysfunction are increasingly recognized as early cardiovascular signals in women with PCOS. Across available studies, elevated RHR, reduced HRV, and sympathetic predominance appear consistently, even in women without obesity or overt metabolic disease. These alterations reflect underlying metabolic, inflammatory, and hormonal disturbances and may precede measurable vascular changes. Because RHR is simple, inexpensive, and compatible with both clinical measurements and wearable devices, it represents a practical supplementary marker for early cardiovascular assessment in PCOS, although it should be interpreted alongside established metabolic and endocrine parameters.

Methodological heterogeneity substantially limits the interpretation of autonomic findings in PCOS. Variability in HRV recording duration (5-min ECG vs. 24-h Holter), body position, menstrual phase, time of day, and analytical domains (time vs. frequency), along with inadequate adjustment for obesity, insulin resistance, cardiorespiratory fitness, and medication use, impedes cross-study comparability and precludes pooled quantitative synthesis. Consequently, while sympathetic predominance appears consistent, effect size, clinical thresholds, and prognostic significance remain uncertain. Autonomic imbalance is common in PCOS; resting tachycardia may aid early detection, and traditional risk tools often underestimate cardiovascular risk in young women. To clarify whether autonomic abnormalities are intrinsic or secondary to metabolic burden, standardized autonomic protocols, longitudinal studies, and careful confounder control are essential. Incorporating RHR and HRV into broader risk-profiling models may improve early prevention strategies, but further research is required to define predictive thresholds and their precise clinical role in guiding cardiometabolic interventions.

ANS: autonomic nervous system

BMI: body mass index

CIMT: carotid intima-media thickness

CPC: cardiopulmonary coupling

CRP: C-reactive protein

ECG: electrocardiogram

FMD: flow-mediated dilation

HF: high frequency

HFnu: high frequency normalized units

HRV: heart rate variability

LF: low frequency

MSNA: muscle sympathetic nerve activity

NIH: National Institutes of Health

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome

pNN50: percentage of NN intervals greater than 50 milliseconds

RHR: resting heart rate

rMSSD: root mean square of successive differences

SDNN: standard deviation of NN intervals

AWI: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. PM: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SB: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. HSW: Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 28

Download: 8

Times Cited: 0