Affiliation:

1Department of Translational Medical Sciences, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, 80100 Naples, Italy

2Division of Cardiology, A.O.R.N. “Sant’Anna e San Sebastiano”, 81100 Caserta, Italy

Email: arturo.cesaro@unicampania.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4435-1235

Affiliation:

1Department of Translational Medical Sciences, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, 80100 Naples, Italy

2Division of Cardiology, A.O.R.N. “Sant’Anna e San Sebastiano”, 81100 Caserta, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5018-830X

Affiliation:

3UOSD Riabilitazione Cardiologica PO San Gennaro ASL Napoli 1 Centro, 80100 Naples, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0611-6234

Affiliation:

4Department of Internal Medicine, Federico II University, School of Medicine, 80131 Naples, Italy

Email: fazio0502@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2743-9836

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101294 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101294

Received: December 16, 2025 Accepted: January 26, 2026 Published: February 11, 2026

Academic Editor: David S.H Bell, University of Alabama, USA

Heart failure (HF) is still one of the most common causes of death today. The vast majority of heart diseases end up leading to HF, which therefore has a high prevalence in the adult population (on average 1–2%), and which increases enormously (over 10%) after the age of 65, becoming the most frequent cause of hospitalization for these subjects. It is therefore necessary to increase efforts to deepen our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to HF and its worsening, particularly with regard to hormonal-metabolic derangements as contributors to HF development and progression. This, in the hope of being able, in the near future, to intervene on them, reducing the prevalence of this pathology and its economic impact on countries’ healthcare spending. To this aim, we performed a narrative review of the scientific literature on the interactions between both insulin and the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 axis and the cardiovascular system, and in particular, to verify the role that these hormones may play in the development and negative progression of HF.

Heart failure (HF) is still one of the most common causes of death and hospitalization, resulting in high costs to public health [1, 2]. There are many causes of HF: ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, valvular disorders, congenital heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity can all lead to HF. HF can be classified according to the severity of symptoms (NYHA classification), which assesses the limitation of physical activity, and according to the ejection fraction (EF) of the left ventricle (LV), which measures the ability to pump blood. This latter divides HF into reduced [heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) ≤ 40%], preserved [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) ≥ 50%], and mildly reduced [heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) 41–49%] [3, 4]. Also, right ventricular dysfunction may be a cause of HF as a result of alterations in pulmonary circulation and lung parenchyma (pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary embolism, COPD, etc.) [5].

HF has a prevalence of about 1–2% in the adult population, but this increases significantly with age, exceeding 10% after the age of 65, becoming the most frequent cause of hospital admissions after the age of 65 [6]. This is despite the significant progress made in recent decades in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease and in understanding the mechanisms that cause HF. It is true, however, that while in the past people often died from ischemic heart disease and acute myocardial infarction, today, with the advent of interventional therapy, coronary angioplasty, and the implantation of devices to control arrhythmias, heart patients survive longer but, very often, develop HF over the years. For this reason, there is a growing effort to improve knowledge of the pathophysiological mechanisms that can lead to the development and/or progression of HF, in the hope of being able to reduce the prevalence of this pathology and improve its outcomes. Among these, the interactions between insulin and growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and the cardiovascular system in the context of HF have been considered fairly recently [7–11].

Insulin is a peptide hormone produced by the beta cells of the pancreas, well known even to non-medical professionals for its role in regulating blood sugar levels, allowing glucose to enter cells to be used for energy production. However, it is now well known that it has many other lesser-known actions which, if unregulated, can cause damage to our body, particularly at the cardiovascular level in conditions of insulin resistance (IR) [12–14].

IGF-1 is a protein hormone with a structure very similar to that of insulin, hence its name, which plays an important anabolic role. It is produced by the liver in response to GH and primarily promotes bone and tissue growth. The GH/IGF-1 axis plays an important role in the cardiovascular system by regulating growth, contractility, and cardiac metabolism, and by influencing the vascular system [15–17].

This is a narrative review with a structured literature search that aims to analyze the scientific data in the literature on this topic, seeking to shed as much light as possible on the mechanisms linking these hormones to the development and progression of HF, and on the potential treatments that could be implemented based on this knowledge. The studies selected for this review were searched for among those published from 1990 to the present day in the most widely used databases, such as PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Research Gate, Google Scholar, etc., using the keywords: heart failure, insulin, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia (HI), growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, cardiovascular diseases. Only studies with a correct design published in English in high-impact journals were considered. Two authors (SF and AC) have independently read and analyzed the manuscripts found, sharing the results.

IR is a pathological condition that is now widespread worldwide. It can have genetic causes, but is mainly secondary to unhealthy lifestyles [14], in particular, increased caloric intake with excessive consumption of carbohydrates and lack of physical activity, so much so that it is associated with overweight, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. In IR conditions, a certain amount of insulin, due to malfunctioning of its receptor and/or certain post-receptor pathways [in particular that of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)], has an insufficient effect on the regulation of glucose metabolism. For this reason, the resulting tendency towards hyperglycemia causes the β cells of the pancreas to produce greater amounts of insulin, particularly after meals rich in carbohydrates, in an attempt to maintain blood glucose within the normal range. As a result, circulating insulin levels increase chronically, making HI a distinctive and constant feature of IR conditions [14, 18]. IR has an average prevalence of approximately 42.2% in Indonesia, even reaching 46.7% in some particular populations [19, 20]. However, a recent systematic review with meta-analysis, which included eighty-seven studies with a total of 235,148 participants, in whom IR was obtained using the homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR), showed a 26.53% prevalence of IR [21]. The gold standard for the diagnosis of IR is the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp, which, however, is too complex to be used for diagnostic purposes and should be reserved for scientific research purposes only [22]. However, there are many surrogate indices that have been shown to correlate well with the clamp and to be indicative of increased cardiovascular risk. The most common are the HOMA-IR, which takes into account the simultaneous measurement of fasting insulin and blood glucose levels, the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG), which is calculated using a formula that takes into account fasting triglyceride and blood glucose levels, and the ratio of triglycerides (TG) to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDLc), which is calculated based on TG and HDLc values also measured in the fasting state [23–26].

HFpEF is a pathological condition in which the heart is affected by concentric remodeling of the LV with increased wall stiffness, making it difficult to relax. As a result, the cavity fills with increased end-diastolic pressure in the ventricle and, upstream, in the pulmonary capillaries, but still has normal pumping capacity (EF). It manifests clinically with the classic symptoms of HF, such as dyspnea and easy fatigue. Unlike HFrEF therapy, the treatment of these forms is not standardized, is complex, and often requires personalized treatments tailored to specific patient subgroups and their characteristics [27]. HFpEF now accounts for 50% of HF cases and has been steadily increasing in recent years, partly due to the aging population [28]. IR has a high prevalence in HFpEF, occurring in over 50% of patients with HF [29, 30]. In these patients, it can be an important cause, or at least a contributing factor, in the development and worsening of HF.

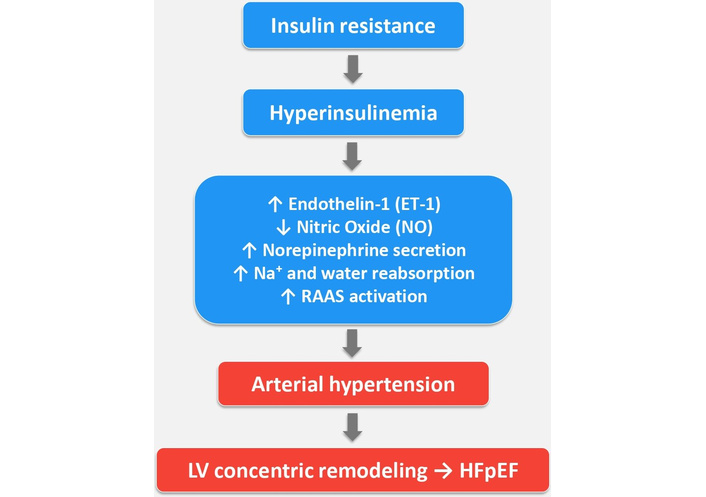

The chronic HI characteristic of IR, while on the one hand playing a positive role in attempting to maintain blood sugar within a normal range, unfortunately, on the other hand, plays a very negative role in relation to the cardiovascular system [14, 18, 31]. Below, we will see why. The insulin IGF-1-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway has been suggested to improve cardiac inotropism and increase Ca2+ handling through the effects of the protein kinase Akt [32]. However, in IR conditions, while the PI3K pathway functions poorly, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is little or not at all altered, so that increased levels of circulating insulin hyperstimulate this pathway, causing significant alterations in cardiocirculatory homeostasis. In this regard, it should be noted that in conditions of IR, high levels of circulating insulin, in addition to controlling carbohydrate metabolism, cause reduced secretion of nitric oxide (NO) at the vascular level. At the same time, they cause an increase in endothelin-1 (ET-1) secretion. For this reason, there is an imbalance in vascular homeostasis in the vasoconstrictive sense. ET-1 is a peptide hormone that acts through specific receptors to activate the MAPK pathway, regulating physiological processes such as vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling, but also pathophysiological processes such as tumor progression. In summary, MAPK is the cellular signaling mechanism, while ET-1 is an external signal that activates this pathway. Together, these effects lead to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis [31].

HI has also been found to be associated with increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system. In fact, it has been shown that increased levels of insulin lead to increased secretion of norepinephrine. This also stimulates vasoconstriction. Furthermore, insulin receptors have been demonstrated in the renal tubules. Overstimulation of these renal receptors in the tubules leads to increased reabsorption of sodium and water, resulting in an expansion of blood volume (hypervolemia). Insulin and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) are closely linked, with IR hyperactivating the RAAS, and in turn, the RAAS worsening IR. This negative feedback loop contributes to cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes, as angiotensin II (a component of the RAAS) impairs insulin signaling, induces inflammation, and causes vasoconstriction [33]. All these associated mechanisms may significantly contribute to the development of some forms of hypertension, actually classified as essential or primary hypertension (Figure 1).

Hyperinsulinemia associated with insulin resistance through various mechanisms causes hypertension with consequent concentric remodeling of LV, which, in the long term, may facilitate the development of HFpEF. ↑: increased; ↓: decreased; LV: left ventricle; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

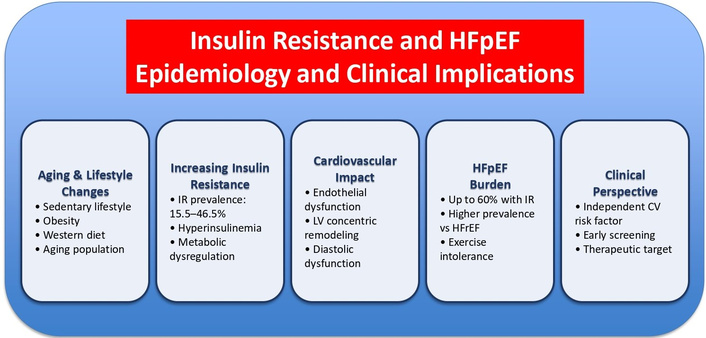

Insulin itself, via the MAPK pathway and through its binding to the IGF receptor, stimulates cell growth at various levels, but for our purposes, we are particularly interested in the stimulation of growth in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes [34, 35]. In addition, HI also promotes the deposition of intramyocardial and epicardial adipose tissue, promoting atherosclerosis on the one hand and myocardial hypertrophy on the other [36–38]. In IR conditions, the myocardium also becomes less responsive to insulin, impairing its ability to use glucose for energy. This leads to the heart relying more heavily on fatty acids, causing cellular stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative damage, which can contribute to HF over time [38, 39]. Other factors like inflammation, lipotoxicity, and impaired calcium handling further contribute to cardiac dysfunction [40, 41]. It has been demonstrated that all these pathological mechanisms triggered simultaneously by HI associated with IR produce, both directly and indirectly, through the triggering of arterial hypertension, an increase in LV mass, also due to an increase in intramyocardial and epicardial fat, with concentric LV remodeling, increased myocardial fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction. All of this ultimately leads to the development and/or worsening of HFpEF over time, if already present [42] (Figure 2). However, the relationship between IR/HI and HF should not be considered unidirectional since HF may also contribute to IR development, creating a self-perpetuating vicious circle [43].

It schematically shows the epidemiological data and the possible clinical implications existing between IR and HFpEF. CV: cardiovascular; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LV: left ventricle.

Based on the above, we believe that it would be useful to identify individuals with IR both before they develop HF and during the course of HF in order to attempt to prevent or, at least, slow down the negative progression of HF, including through interventions designed to counteract IR.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) (a protein located in the kidneys that reabsorbs glucose and sodium from the filtrate and returns them to the blood) inhibitors have been shown to improve IR by eliminating large amounts of glucose through urine [44–46]. This reduces the need for the pancreas to produce insulin, thereby reducing circulating insulin levels and improving insulin sensitivity in tissues such as muscles, fat, liver, etc. [47, 48]. They also reduce the chronic inflammation associated with IR [49]. Through these effects and the reduction of insulinemia, they can attenuate the described deleterious effects of HI on the cardiovascular system. In fact, numerous studies show that this class of drugs significantly improves outcomes in patients with HF, reducing hospitalizations and cardiovascular deaths [50–54].

GLP-1 RAs have been shown to improve IR through mechanisms other than just reducing body weight and obesity [55]. In fact, they have been shown to reduce IR many weeks before having an effect on body weight reduction [55]. These substances can increase insulin sensitivity and, therefore, circulating insulin levels by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress and increasing the expression of glucose transporters in insulin-dependent tissues, even though, in the first instance, they would directly stimulate pancreatic beta cells to produce more insulin and inhibit glucagon secretion [56–58]. In addition to their effectiveness in treating type 2 diabetes and obesity, GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated clear cardiovascular benefits in the treatment of HFpEF [59, 60]. It appears that they act both indirectly, through weight loss and systemic metabolic improvement, and directly on the myocardium, although the presence of functional GLP-1 receptors in the myocardium (except in the atrial myocardium and sinoatrial node) is uncertain [61]. Experimental studies in animals have shown that GLP-1 increases myocardial glucose utilization, shifting fatty acid metabolism towards carbohydrate oxidation [62]. In addition, GLP-1 receptors are expressed in endothelial cells, and activation of these GLP-1 receptors improves endothelial function by increasing NO availability, resulting in reduced arterial resistance [63]. In animal models, GLP-1 RAs have also inhibited myocardial fibrosis and reduced LV hypertrophy [64]. However, most of these beneficial mechanisms of GLP-1 RAs could be partly explained by the fact that they improve IR and, consequently, the insulin required for good glycemic control is reduced [55, 65]. We have seen that higher circulating insulin levels associated with IR can trigger those harmful mechanisms that may be counteracted by GLP-1 RA therapy.

Metformin belongs to the class of biguanides, drugs known to lower blood sugar through a beneficial effect of reducing IR and circulating insulin levels. It has been around for over 60 years and is still the drug recommended by US and European guidelines as the first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes, which is the form of diabetes resulting from IR [66, 67]. Metformin counteracts IR by decreasing glucose production in the liver and intestinal glucose absorption. In addition, it increases insulin sensitivity and glucose transport into cells by increasing the expression and translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) [67, 68]. This is achieved through the activation by metformin of the enzyme AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which in turn stimulates GLUT4 activity [69, 70]. Through these insulin sensitization mechanisms, metformin is able to reduce the chronically elevated circulating levels of insulin in conditions of IR [70].

Some studies show that treatment with metformin is associated with a lower risk of hospitalizations for all causes and HF-related hospitalizations. In addition, some meta-analyses have shown a significant reduction in all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with HF treated with metformin compared to other antidiabetic drugs [71, 72]. The risk of lactic acidosis associated with metformin in patients with HF has been downplayed, mainly affecting patients with specific associated conditions (severe kidney or liver disease, excessive alcohol consumption, dehydration) [73, 74]. Metformin is currently being studied for its potential role in the treatment of HFpEF, mainly because many patients with this condition also have type 2 diabetes, and metformin could be beneficial in these patients by counteracting IR and reducing the HI associated with it and, therefore, the cardiovascular damage caused by this condition (DANHEART; H-HeFT and Met-HeFT; ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT03514108; CARMET; ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01690091).

Berberine is a yellow, bitter-tasting alkaloid extracted from plants of the Berberis genus. It has been used in Chinese and Indian Ayurvedic medicine for over 2,000 years for its effectiveness in treating various pathological conditions, but in recent decades, it has come to our attention for its metabolic and cardiovascular health effects [75]. It works by improving glucose metabolism and reducing fasting glucose levels. It counteracts IR and HI through a mechanism similar to that of metformin, i.e., by activating the AMPK enzyme [75–77]. It can help reduce LDL cholesterol and TG and is considered a powerful natural anti-inflammatory. Some studies suggest that it may have protective effects on the liver by preventing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [77, 78].

There is a fair amount of preclinical scientific literature supporting the fact that berberine can help patients with HF by improving cardiac function and inhibiting pathological cardiac remodeling through several mechanisms, including protecting myocardial cells from apoptosis and increasing mitochondrial health [79, 80]. However, further large clinical, randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm its efficacy in patients with HF and IR.

GH is secreted by the anterior pituitary in a pulsatile fashion and stimulates hepatic production of IGF-1, the main mediator of its anabolic and metabolic effects. The GH/IGF-1 axis is tightly regulated by hypothalamic hormones, nutritional status, sleep, physical activity, and several metabolic signals, including insulin and adipokines.

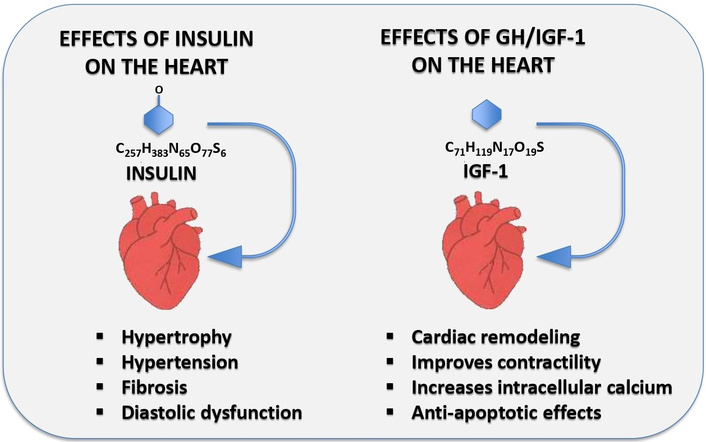

Both GH and IGF-1 exert relevant actions on the cardiovascular system. GH receptors and IGF-1 receptors are expressed in cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and vascular cells, including endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Experimental and human data indicate that physiological activation of this axis promotes adaptive cardiac hypertrophy, improves myocardial contractility and calcium handling, enhances endothelial NO production, and exerts anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Castellano et al. [9] and Arcopinto et al. [11] have comprehensively reviewed how GH/IGF-1 signaling modulates LV growth, systolic function, and vascular tone in both normal and failing hearts.

More recent work by Higashi et al. [15] and Werner [35] has highlighted that IGF-1 also improves endothelial function, mitochondrial integrity, and oxidative stress resistance, suggesting a broader vasculoprotective and cardioprotective role.

In physiological conditions, therefore, the GH/IGF-1 axis supports cardiac performance and vascular homeostasis. Both deficiency and excess, however, as well as alterations in IGF-1 bioavailability, are associated with adverse cardiac remodeling and an increased risk of HF [81].

Adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD) provides a natural model of chronic impairment of GH/IGF-1 signaling. Patients with GHD typically present with increased visceral adiposity, dyslipidemia, endothelial dysfunction, and reduced exercise capacity—a phenotype that overlaps with cardiometabolic HF. Cardiac imaging studies have shown that adults with GHD have reduced LV mass, impaired systolic and diastolic function, and lower stroke volume compared with age- and sex-matched controls [82–84].

Cardiac magnetic resonance and echocardiographic data consistently indicate that LV mass index in adult-onset GHD lies at or below the lower limit of normal, and that one year of GH replacement increases LV mass, wall thickness, and stroke volume, while improving global longitudinal strain and exercise tolerance [85, 86].

These findings support the concept that physiological GH/IGF-1 signaling is required to maintain adequate myocardial structure and performance.

Beyond “overt” GHD, several observational studies have linked low circulating IGF-1 levels in the general population with a higher risk of incident cardiovascular disease and HF [86, 87]. A large prospective cohort showed a non-linear association between IGF-1 and cardiovascular events, with both low and high IGF-1 concentrations associated with increased risk, suggesting the existence of an “optimal” IGF-1 range for cardiovascular health [81].

A recent meta-analysis focusing on IGF-1 and HF reported that reduced IGF-1 levels are frequently observed in HF patients and are associated with higher HF incidence and HF-related mortality [88].

Mechanistically, low IGF-1 may contribute to HF through several pathways: a) the loss of anti-apoptotic signaling in cardiomyocytes, with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and neurohormonal activation; b) impaired endothelial function and reduced NO bioavailability, which favor microvascular dysfunction and increase ventricular afterload; c) worsened skeletal muscle function and sarcopenia, further limiting exercise capacity and promoting the HF frailty phenotype [88].

These alterations are particularly relevant in HFpEF, where concentric LV remodeling, diastolic dysfunction, microvascular inflammation, and peripheral limitations to exercise play a major pathophysiological role. In this setting, low-normal IGF-1 levels may act synergistically with IR, visceral obesity, and systemic inflammation to promote the so-called “metabolic HFpEF” phenotype.

In HF, both hepatic and peripheral resistance to GH is possible. The first is characterized by reduced hepatic IGF-1 production following GH stimulation, with a reduction of the effects of IGF-1 on growth, anabolism, and feedback regulation of GH. While the second is characterized by deficient effects directly on GH at the peripheral level, independently of IGF-1, such as those on metabolism, body composition, cardiovascular function, and cellular growth [89].

Several studies have described a state of acquired GH resistance in advanced HF, with normal or increased circulating GH levels but relatively low or inappropriately normal IGF-1 concentrations [11].

This pattern resembles other catabolic states such as chronic kidney disease, malnutrition, and cachexia, in which inflammatory cytokines, hepatic dysfunction, and alterations in GH receptor signaling blunt the IGF-1 response to GH [90, 91].

The severity of HF is associated with progressive blunting of GH/IGF-1 activity, with lower IGF-1 levels correlating with more advanced symptoms, reduced exercise capacity, and worse prognosis [92].

Both low IGF-1 and excessive IGF-1 (as in acromegaly) are linked to a higher HF risk.

Several mechanisms may explain GH resistance in HF: a) the systemic inflammation and elevated cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) downregulate GH receptors and post-receptor signaling in the liver and peripheral tissues; b) the hepatic congestion and dysfunction reduce IGF-1 synthesis and alter IGF-binding protein (IGFBP) profiles, limiting free, bioactive IGF-1; c) the neurohormonal activation and chronic sympathetic hyperactivity further perturb GH secretion patterns and IGF-1 production [93–96].

These alterations contribute to a vicious circle: reduced GH/IGF-1 signaling promotes skeletal muscle wasting, reduced peak VO2, impaired myocardial energetics, and progressive decline in functional capacity, which in turn worsens HF outcomes [11]. HF patients who should be screened for GH/IGF-1 abnormalities are those with severe disease, poor functional capacity, high mortality risk, or specific conditions like polytransfused patients, as low IGF-1 levels often signal worse outcomes, making screening useful for prognosis and potentially guiding therapy [97]. Because insulin and IGF-1 share the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade, disturbances in one system directly affect the activity of the other. In HF, systemic IR inhibits PI3K/Akt signaling, reduces hepatic IGF-1 synthesis, alters IGF-binding protein profiles, and impairs IGF-1 receptor phosphorylation [88, 98]. As a result, even normal GH secretion leads to insufficient IGF-1 bioactivity (“GH resistance”). Conversely, reduced IGF-1 signaling worsens glucose uptake, inflammation, and skeletal muscle catabolism, thereby exacerbating IR. This bidirectional interaction creates a vicious cycle that amplifies endothelial dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, impaired energetics, and the progression of both HFpEF and HFrEF.

Acromegaly, characterized by chronic GH and IGF-1 excess, represents the opposite extreme of GH/IGF-1 derangement. Patients with uncontrolled acromegaly often develop a specific acromegalic cardiomyopathy, initially characterized by concentric LV hypertrophy and increased cardiac output, and later progressing to diastolic dysfunction, systolic impairment, and, in a minority of patients, overt HF [99].

Histological and imaging studies describe myocyte hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and microvascular changes, with impaired diastolic relaxation and, in advanced stages, reduced EF. The adequate biochemical control of acromegaly (normalization of GH and IGF-1 levels) can lead to partial regression of LV hypertrophy and improvement in diastolic function, especially when treatment is initiated in earlier disease stages [100, 101].

Recent epidemiological data suggest that, after adjusting for disease control and classical cardiovascular risk factors, the risk of HF in acromegaly may approach that of the general population, reinforcing the concept that duration and degree of hormonal excess are critical determinants of cardiac outcomes [102].

Nevertheless, acromegaly clearly illustrates that chronic, marked GH/IGF-1 excess can be deleterious for the heart, promoting pathological hypertrophy and HF in susceptible individuals.

Taken together, data from GHD and acromegaly support a U-shaped relationship between IGF-1 and cardiovascular risk, in line with large population cohorts: both insufficient and excessive IGF-1 signaling may predispose to HF.

Given the biological rationale, GH or IGF-1 supplementation has long been considered a potential therapeutic strategy in HF. Early small, uncontrolled, or open-label studies suggested that GH administration in patients with HFrEF could increase LV mass, improve EF, and enhance exercise capacity. These promising findings, however, were followed by heterogeneous randomized, placebo-controlled trials with inconsistent results, limited by small sample sizes, variable dosing regimens, and lack of stratification according to baseline GH/IGF-1 status.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of GH therapy in chronic HF concluded that, overall, GH treatment may improve several surrogate endpoints (LV mass, LV dimensions, peak VO2), but the quality of evidence is low and data on hard clinical outcomes and long-term safety remain insufficient [103].

More recently, attention has shifted toward targeted GH replacement in HF patients with documented GHD, rather than indiscriminate GH use. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (Treatment of GHD Associated With CHF; NCT03775993) showed that GH replacement in HFrEF patients with coexisting GHD led to improvements in LV and right ventricular structure and function, exercise performance, and quality of life, without major safety concerns over the study period [104].

These data support the concept that correcting a true hormonal deficiency, rather than “super-physiological” GH administration, may be beneficial in selected HF patients.

Attempts to use IGF-1 or IGF-1 analogues in HF have been more limited. Short-term IGF-1 infusion has been shown to enhance endothelial function and increase cardiac output in experimental settings, but concerns about potential pro-proliferative and oncogenic effects, together with the complex non-linear relationship between IGF-1 and cardiovascular events, have limited clinical translation.

Beyond pharmacologic replacement, several non-pharmacological interventions can modulate the GH/IGF-1 axis: a) regular physical activity and cardiac rehabilitation increase physiological GH pulsatility and IGF-1 levels, improving skeletal muscle function and exercise capacity, b) nutritional optimization and correction of cachexia support IGF-1 synthesis and may partially reverse GH resistance, c) treatment of IR and obesity (e.g., with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs) may indirectly normalize GH/IGF-1 dynamics by improving metabolic status, sleep quality and systemic inflammation, thus creating a more favorable hormonal milieu for the failing heart.

At present, therefore, GH/IGF-1-directed therapies cannot be recommended broadly for HF, but personalized approaches in clearly defined subgroups (such as HFrEF with confirmed GHD) appear promising and warrant further investigation in larger, rigorously designed trials.

This narrative review shows that there are many interrelationships among IR with associated HI, GH /IGF-1 axis, and HF. The GH/IGF-1 axis does not act in isolation. Insulin, GH, and IGF-1 share overlapping intracellular pathways, especially PI3K/Akt signaling, and have reciprocal effects on substrate metabolism, body composition, and vascular function.

In conditions of IR, as discussed in the previous section, impaired PI3K signaling and compensatory HI lead to endothelial dysfunction, activation of MAPK pathways, sodium retention, LV hypertrophy, and concentric remodeling, ultimately favoring HFpEF.

At the same time, chronic inflammation, visceral adiposity, and hepatic steatosis—hallmark features of IR—can blunt GH receptor signaling and reduce IGF-1 bioavailability, promoting GH resistance and further impairing myocardial and skeletal muscle function.

Conversely, both GH deficiency and chronic GH excess worsen insulin sensitivity, creating a complex bidirectional relationship between GH/IGF-1 derangements and IR. GHD is associated with increased visceral fat and dyslipidemia, while GH excess in acromegaly induces IR and glucose intolerance, adding cardiometabolic burden to the direct myocardial effects of GH/IGF-1 excess.

Overall, current evidence supports a model in which subtle or overt disturbances of the GH/IGF-1 axis interact with IR and other neurohormonal systems to promote HF development and progression. Reduced IGF-1 signaling and acquired GH resistance appear particularly relevant in chronic HF and HFpEF, contributing to myocardial dysfunction, endothelial impairment, skeletal muscle wasting, and poor functional capacity. On the other hand, chronic GH/IGF-1 excess, as in uncontrolled acromegaly, can drive pathological hypertrophy and HF in susceptible patients (Figure 3).

This figure shows the main effects of insulin and the GH/IGF-1 axis on the cardiovascular system.

Recent studies have further emphasized the tight interconnection between metabolic dysregulation, inflammatory signaling, and endocrine alterations in cardiovascular disease, supporting an integrated pathophysiological model [41]. In this context, interventions that correct IR, improve metabolic health, and restore a more physiologic GH/IGF-1 profile—including lifestyle measures, novel cardiometabolic drugs, and in selected cases, targeted GH replacement—may represent complementary strategies to standard HF therapies aimed at modifying not only hemodynamics and neurohormonal activation, but also the hormonal and metabolic milieu of the failing heart.

AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase

EF: ejection fraction

ET-1: endothelin-1

GH: growth hormone

GHD: growth hormone deficiency

GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1

GLUT4: glucose transporter 4

HDLc: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

HF: heart failure

HFmrEF: heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

HI: hyperinsulinemia

HOMA-IR: homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1

IR: insulin resistance

LV: left ventricle

MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NO: nitric oxide

PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

RAs: receptor agonists

SGLT2: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

TG: triglycerides

TyG: triglyceride-glucose index

SF and AC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. PC: Validation, Supervision. AR: Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 33

Download: 3

Times Cited: 0