Affiliation:

Department of Cardiology, Hospital of Braga, 4710-243 Braga, Portugal

Email: monica.dias_96@hotmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5206-7993

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101292 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101292

Received: December 19, 2025 Accepted: January 26, 2026 Published: February 04, 2026

Academic Editor: Ping Liang, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a rare but potentially life-threatening inherited arrhythmia disorder, often presenting in childhood or adolescence. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical, as untreated CPVT carries a high risk of sudden cardiac death, particularly in young individuals. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion and employing a systematic diagnostic approach. We highlight the value of integrating clinical history, family background, and targeted investigations in evaluating young adults presenting with sudden cardiac arrest. Prompt recognition and diagnosis of CPVT may be lifesaving and have significant implications for both patients and their families.

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is an inherited arrhythmogenic disease predominantly affecting children and young adults. Although rare, CPVT is a well-established cause of cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death [1].

The pathogenesis of the disease centers on mutations in genes encoding the cardiac ryanodine receptor 2 (RYR2, autosomal dominant) and calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2, autosomal recessive), leading to abnormal calcium handling in cardiomyocytes. This results in delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered activity, which manifest as exercise- or emotion-induced bidirectional or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) that can rapidly degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest [1–3].

Diagnostic challenges arise because CPVT patients typically have structurally normal hearts and a normal baseline ECG. Arrhythmia is often only unmasked during exercise stress testing, which reveals the characteristic bidirectional or polymorphic VT. There is frequently a delay in diagnosis, with many patients experiencing recurrent syncope or even cardiac arrest before CPVT is identified. Genetic testing is recommended for confirmation and risk stratification [1, 3].

First-line treatment is high-dose non-selective beta-blocker therapy to reduce mortality. For those with recurrent arrhythmias despite beta-blocker therapy, flecainide is added, and left cardiac sympathetic denervation may be considered [4, 5]. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are reserved for those recovering from sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) or refractory arrhythmias, though complications are common [6, 7]. Ongoing research into gene-targeted therapies and precision medicine approaches is underway [8].

SCA in young age is rare and requires intensive investigation to find the underlying cause, since proper treatment may radically change the prognosis [9].

Here, we report a case of a 25-year-old man who presents with SCA, in which a critical review of the patient’s background and a systematic diagnostic workup led to the final diagnosis of CPVT. Recognizing CPVT early is crucial for initiating appropriate management and preventing fatal outcomes, with important implications for both affected individuals and their relatives. With this case, we hope to highlight the importance of pursuing etiological studies in young patients presenting with SCA, leading to a quick diagnosis that might prevent a serious outcome for patients and their families.

A 25-year-old man experienced a cardiac arrest while watching a football game. Medical assistance arrived within 10 minutes, and a ventricular fibrillation was recorded and successfully aborted after electrical defibrillation, resulting in return of spontaneous rhythm and circulation. After stabilization in the intensive care unit, the patient was transferred to the cardiology ward for further investigation. His clinical background included epilepsy, for which he was being treated with sodium valproate. There was no family history of cardiac disease or sudden death.

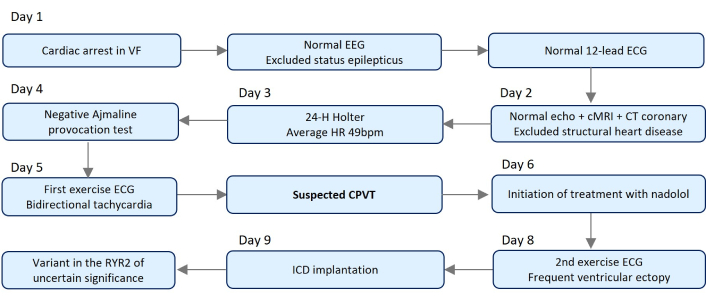

An etiologic study was performed and the diagnostic approach timeline is summarized in Figure 1.

Timeline of the diagnostic approach. cMRI: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; CT: computed tomography; HR: heart rate; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; RYR2: ryanodine receptor 2.

Electroencephalogram at admission showed absence of epileptic activity and excluded non-convulsive status epilepticus. The first 12-lead ECG was on sinus rhythm with a normal QT interval (Figure 2). Echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance revealed a normal structure and function of the heart, and the computed tomography (CT) coronary angiogram showed normal origin of coronary arteries and absence of coronary artery disease. Toxicology screening for drugs of abuse was negative on admission.

An in-depth anamnesis highlighted that the epilepsy diagnosis had been made during childhood, following several episodes resembling absence seizures, always triggered by stress, which resolved spontaneously. Previous electroencephalograms showed no abnormal electrical activity, cerebral magnetic resonance imaging was free of pathological findings, and genetic testing for epilepsy was negative. Furthermore, epileptic seizures were never documented. All these findings raised the suspicion of an arrhythmogenic disease.

Subsequently, modified precordial ECG leads (V1–V3) showed no Brugada pattern and pharmacological provocation with ajmaline (1 mg/kg over 5 minutes) under continuous ECG monitoring did not induce a type 1 Brugada pattern. Twenty-four-hour Holter monitoring showed rare and isolated premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), with a mean heart rate of 49 beats per minute (bpm).

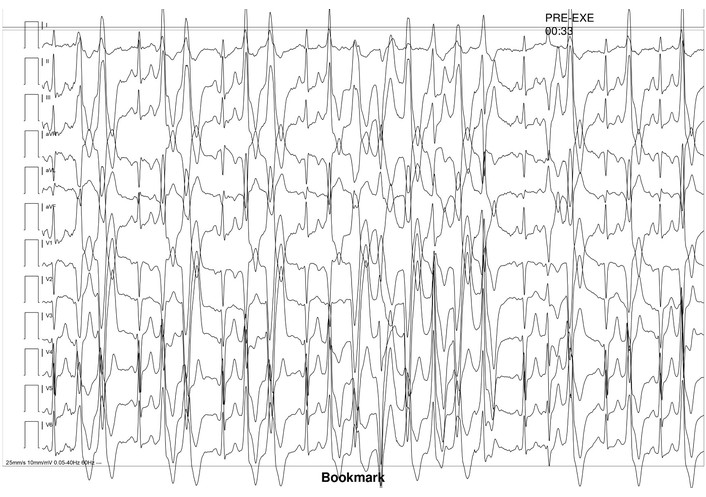

A maximal-effort, burst exercise stress testing with continuous ECG monitoring using the standard Bruce protocol was performed to assess for arrhythmias under increasing workload, and revealed exercise-induced PVC, which rapidly progressed into polymorphic PVC and non-sustained VT, with some bidirectional beats at four minutes of exercise, prompting early termination of the test (Figure 3). This raised suspicion of CPVT.

Exercise ECG revealing exercise-induced premature ventricular contractions, progressing to non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, with some bidirectional beats.

The patient was started on beta-blocker therapy with nadolol at a daily dose of 40 mg. A follow-up exercise test revealed frequent ventricular ectopy at the peak of exercise, leading to an increase in nadolol dosage to 60 mg daily (1 mg/kg). Transvenous ICD was implanted for secondary prevention. The suppression of ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) was confirmed and periodically reassessed through exercise stress testing.

Genetic testing identified a variant of uncertain significance in the RYR2 gene, which encodes the cardiac RYR, supporting the diagnosis and the ongoing treatment. Family cascade screening was performed and the results are pending.

The patient has remained asymptomatic under beta-blocker therapy, with no recorded recurrence of arrhythmic events.

We present a case of a young man with a previous diagnosis of epilepsy who was admitted to our emergency department with SCA of unknown cause.

Cardiac arrest may occur because of a well-known disease or be the first presentation of an unknown condition. A large portion of the young patients presenting with SCA have never been diagnosed with structural heart disease or inherited arrhythmia syndrome before presentation, as the one here presented, making the diagnostic workup much more challenging [9–11].

When approaching an aborted cardiac arrest in a young age, some causes must come to mind: cardiac causes (such as myocarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, or primary arrhythmogenic disorders), airway diseases, epilepsy, or drug toxicity [9, 11–15] (Table 1).

Main potential causes of cardiac arrest in young patients.

| Category | Cause | Typical context | Diagnostic/Screening approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac structural | Myocarditis | Viral illness, post-infectious, post-vaccination | cMRI; endomyocardial biopsy in selected cases |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Most common inherited cause; high risk in athletes | Echocardiography/cMRI; family screening; genetic testing | |

| ARVC | Exercise-related arrest; ventricular arrhythmias | Holter monitoring, echocardiography; cMRI, and genetic testing | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | Genetic, toxic, or inflammatory; may be asymptomatic | Echocardiography/cMRI; genetic testing; family screening | |

| Congenital heart disease | Repaired or unrepaired lesions | Echocardiography; cMRI/CT; review of surgical history | |

| Coronary artery anomalies | Sudden collapse during exertion, especially in athletes | Coronary CT angiography or cMRI | |

| Premature coronary artery disease | Smoking, familial hypercholesterolemia, and stimulant use | ECG; echocardiogram, coronary imaging; lipidic profile | |

| Cardiac channelopathies | Long-QT syndrome | Syncope or arrest during exertion, emotion, or rest | ECG (QTc); exercise testing; genetic testing; family screening |

| Brugada syndrome | Arrest during sleep or fever; more common in males | ECG, including high right precordial leads; provocative testing; genetic testing | |

| CPVT | Stress- or exercise-induced ventricular arrhythmias | Exercise stress test; Holter monitoring; genetic testing | |

| WPW syndrome | Rapid atrial arrhythmias degenerating to VF | ECG; electrophysiology study | |

| Non-cardiac | Asthma/Airway disease | Severe exacerbation causing hypoxia | Pulmonary history; spirometry; toxicology if unclear |

| Epilepsy | Unwitnessed arrest, often during sleep | Neurology evaluation; EEG; review seizure control | |

| Drug toxicity | Opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, and QT-prolonging drugs | Toxicology screening; medication review | |

| Pulmonary embolism | Hypercoagulable states, pregnancy, and immobilization | D-dimer; CT pulmonary angiography | |

| Anaphylaxis | Known allergies, recent exposure | Clinical diagnosis; serum tryptase | |

| Idiopathic | Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome | Structurally normal heart at autopsy | Molecular autopsy; genetic testing; cascade family screening |

ARVC: arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy; CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; CT: computed tomography; cMRI: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; VF: ventricular fibrillation; WPW: Wolf-Parkinson-White.

Cardiac arrest triggered by an epileptic seizure was the first clinical hypothesis during the first medical contact. However, the presence of a shockable rhythm was inconsistent with this scenario, and a normal electroencephalogram on admission further ruled out seizure-related causes. Together with the previously described absence-seizure-like episodes occurring under stressful conditions and the lack of documented epilepsy, these findings raised suspicion of a cardiac cause for the SCA and a likely prior misdiagnosis of epilepsy. Beyond that, other potential diagnoses must be ruled out.

At this stage, the differential diagnosis included: (1) previously undiagnosed structural heart disease, (2) drug toxicity, and (3) a cardiac channelopathy or other primary arrhythmogenic disorder.

A systematic approach to clinical testing was performed. It included screening for drugs of abuse, ECG, echocardiogram, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI), exercise test, 24-hour Holter monitoring, and drug provocation to unmask the cause of an unexplained aborted sudden cardiac death and to guide genetic testing of arrhythmic syndromes [16–18]. Most patients, like the one here described, present normal ECG and echocardiogram/cMRI, therefore, the exercise test plays a main role in the differential diagnosis, since it can induce VAs in up to 100% of patients with CPVT [19]. The onset of polymorphic VT with some bidirectional beats favored the diagnosis.

Additionally, genetic analysis identified a mutation in the gene encoding the cardiac RYR, one of the main genes involved in the disease, along with the cardiac CASQ gene [19, 20]. Considering the uncertain significance of the mutation, the final diagnosis of CPVT remains to be determined by the phenotype. Depending on the family screening results, the variant may be reclassified in the future.

I was 25 years old and considered myself healthy when I collapsed while watching a football match. I do not remember the event itself, only waking up in the hospital and being told that my heart had stopped.

Going through multiple tests made me anxious, but it was a relief when the doctors found an explanation for what had been happening to me. Receiving the diagnosis of a heart rhythm condition changed my understanding of previous symptoms and made me more alert to future ones.

Starting treatment and receiving an implantable defibrillator gave me a sense of security and confidence to move forward with my life. Now that I know the condition and the associated risks, I have even started doing some safe, low-intensity exercise (pilates) and continue to have regular checkups at the hospital with my cardiologist. I am grateful that a thorough investigation was carried out, as it may have saved my life.

In CPVT, SCA is caused by a catecholamine-induced bidirectional or polymorphic VT induced by physical or emotional stress, in the absence of structural heart disease or ischemia [5, 12]. This occurs because cardiac tissues in CPVT patients are vulnerable to developing reentrant rhythms when under catecholaminergic stimulus [18].

Regarding other potential mechanisms of polymorphic VT, such as long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, or R-on-T phenomenon, they were all considered and explored as differential diagnoses since they can also manifest as SCA. Further investigation made them less likely to be the underlying cause in this case. In fact, CPVT is a rare finding, with an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000 or less, significantly lower than other inherited arrhythmogenic disorders [1]. For these reasons, the clinician’s suspicion and systematic approach were essential to achieve the diagnosis in this case.

The treatment of CPVT involves the use of non-selective beta-blockers to suppress stress-induced VA [8]. Nadolol is the preferred beta-blocker for CPVT, with recommended initial dosing of 1–2 mg/kg/day [21]. Propranolol is an alternative, but its short half-life and need for multiple daily doses may limit adherence and efficacy [22]. The dose should be individualized and titrated to the maximum tolerated level, with the primary goal of suppressing VA as assessed by exercise stress testing, with periodic reassessment every 6–12 months. Breakthrough arrhythmias despite maximally tolerated nadolol require escalation of therapy, typically with the addition of flecainide, and consideration of left cardiac sympathetic denervation or ICD in refractory cases [4, 5].

While ICD is recommended in SCA survivors, its implantation in this specific population carries a significant risk of complications [5, 23]. Shock therapy, whether appropriate or not, may intensify the adrenergic drive and potentially induce or exacerbate arrhythmias [24, 25]. Additionally, previous studies have observed that shocks delivered for polymorphic and bidirectional VT are usually unsuccessful [6, 7]. This led us to program the ICD with a singular ventricular fibrillation zone at a high threshold (230 bpm) for ventricular fibrillation detection, avoiding inappropriate shocks triggered by non-sustained episodes of bidirectional and polymorphic VT.

Considering the low baseline heart rate of our patient and the need for beta-blocker therapy, a double-chamber transvenous ICD was implanted, allowing bradycardia pacing in case of need. For this, the pacing function was programmed with a base rate of 50 bpm and a rate hysteresis of 40 bpm to privilege the intrinsic rate of the patient.

The optimal approach to these patients also involves personalized recommendations aimed at diminishing adrenergic stimulation. This includes shared decision-making about competitive and intensive leisure-time sports, since recent consensus statements support a more individualized approach. This is particularly relevant for athletes, in whom the participation in competitive sports may be reconsidered after optimized therapy and verification of arrhythmia suppression in a stress test [26, 27].

Additionally, given the genetic basis of CPVT and once the mutation is known or suspected, first-degree relatives should perform genetic testing and initiate treatment with beta-blockers if positive, even in the absence of documented exercise- or stress-induced VA [8]. Nonetheless, current evidence does not support genotype-guided therapy adjustments, and all patients with a clinical diagnosis of CPVT, regardless of genotype, should receive beta-blocker therapy, as well as silent carriers, since sudden cardiac death may be the first manifestation even in asymptomatic individuals [20, 28].

Finally, it is important to emphasize that, given the rarity of the disease, the final diagnosis was likely delayed, which could have had a major prognostic impact. When not properly investigated, symptoms such as those the patient presented may be misattributed to other syndromes and ultimately culminate in sudden death. Moreover, establishing the correct diagnosis has important implications for the patient’s family, particularly regarding the need for targeted screening and genetic testing.

CPVT is a rare inherited disorder of calcium regulation, causing exercise- or stress-induced VAs and SCA, which may be the first presentation of the disease. Misdiagnosis can significantly delay recognition and treatment, which is focused on suppressing adrenergic triggers to prevent sudden death.

In cases of SCA at a young age, inherited arrhythmogenic conditions must always be actively excluded, even when they are not the leading initial diagnostic hypothesis. For this reason, a standardized, protocol-based diagnostic approach in SCA cases, particularly at young ages, to ensure that inherited arrhythmic or other cardiac conditions are not overlooked, is of the essence.

This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and reevaluating initial diagnoses when clinical features do not fully align, and it serves as a reminder for clinicians to integrate cardiac causes early into the diagnostic pathway to improve patient outcomes and enable timely family screening, while reviewing the particularities of CPVT.

bpm: beats per minute

CASQ2: calsequestrin 2

cMRI: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

CT: computed tomography

ICDs: implantable cardioverter-defibrillators

PVCs: premature ventricular contractions

RYR2: ryanodine receptor 2

SCA: sudden cardiac arrest

VAs: ventricular arrhythmias

VT: ventricular tachycardia

Part of this study has been published as a Meeting Abstract and may be consulted in the abstract book of the 13th Challenges in Cardiology. It was presented as an oral communication at the ESC Acute Cardiovascular Care congress 2024, in Athens.

MD: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SF: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. SR: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision. CA: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval is not required for case studies according to the local ethical committee.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Not applicable.

All relevant data are present in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 513

Download: 28

Times Cited: 0