Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Haradoi Hospital, Fukuoka 813-8588, Japan

Email: tmaruyama@haradoi-hospital.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6543-4377

Affiliation:

2The Second Department of Internal Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka 807-8555, Japan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3434-6184

Explor Cardiol. 2026;4:101287 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ec.2026.101287

Received: September 26, 2025 Accepted: November 25, 2025 Published: January 14, 2026

Academic Editor: Ji-min Cao, Shanxi Medical University, China

The article belongs to the special issue Exploring Exercise Cardiology: from Molecules to Humans

Exercise-related arrhythmia is attracting growing attention, according to the increased popularity of leisure-time sports, which have great benefits and acute risk, although the hemodynamics and therapeutics of exercise-related arrhythmia are poorly understood. We have experienced two cases of different types of exercise-related arrhythmias. In an 80-year-old woman, exercise-induced increase in supraventricular premature contractions (SVPCs) converted to atrial fibrillation (AF) during a control ergometric stress test (EST), but SVPCs were diminished, and AF was not observed in the secondary EST after starting bisoprolol. In a 39-year-old woman, idiopathic premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) appeared immediately after the termination of the control EST but were scarcely induced by the secondary EST under the treatment with bisoprolol. Post-exercise abnormal increase in the double product was suppressed, leading to the possibility of improved exercise tolerance in both cases. A couple of ESTs under the same protocol to compare the arrhythmic behaviors with and without treatment provides a therapeutic strategy in exercise-related arrhythmia, and short-term bisoprolol is concluded to be favorable to the specific types of exercise-related arrhythmia, at least in these two cases.

Exercise-related arrhythmia is attracting growing attention, i.e., the incidence of this kind of arrhythmia may increase because of the increased popularity of leisure-time sports. However, the management of exercise-related arrhythmia in physically active people is underexplored, and the hemodynamics of exercise-related arrhythmia are poorly understood [1, 2]. Exercise tests are widely conducted in the affected patients for the purpose of screening, induction, and therapeutics of exercise-related arrhythmia. We have experienced two cases of different types of exercise-related arrhythmias and confirmed the effectiveness of bisoprolol by a couple of symptom-limited ergometric exercise tests with the same protocol.

Timelines of the two cases are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Timeline of clinical events in Case 1.

| Date/Time | Event | Details/Findings | Management/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0—fatigue and dizziness perceived | Referred to our hospital | Diagnosis of dyslipidemia and HF | Dietary lipid and salt restriction |

| Day 1—palpitation perceived | Admission | SVPCs recorded in the ECG | ECG monitoring observation |

| Day 8—dizziness disappeared | Cardiac rehabilitation started | Diet therapy continued | |

| Day 24—palpitation continued | First EST attempted | SVPCs and AF observed in EST | Bisoprolol administered |

| Day 38—palpitation improved | Second EST attempted | SVPCs diminished and AF not induced by EST | Bisoprolol continued |

| Day 48—fatigue improved | Discharge, introduced to the previous clinic | SVPCs diminished in the ECG monitor | Bisoprolol continued, diet therapy continued |

AF: atrial fibrillation; ECG: electrocardiogram; EST: ergometric stress test; HF: heart failure; SVPCs: supraventricular premature contractions.

Timeline of clinical events in Case 2.

| Date/Time | Event | Details/Findings | Management/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 years ago—palpitation perceived | Visit to another clinic | PVCs recorded in the ECG | Administration of propranolol, discontinued due to fatigue |

| Day 0—palpitation perceived | Visit to our clinic | No PVCs recorded in the ECG | Ordering an exercise test |

| Day 28—palpitation continued | First EST attempted | PVCs recorded immediately after EST | Bisoprolol administered |

| Day 42—palpitation disappeared | Second EST attempted | PVCs not induced by EST | Bisoprolol continued |

| Day 70—no palpitation perceived | Monthly visit to our clinic | No PVCs recorded in the ECG | Bisoprolol continued |

ECG: electrocardiogram; EST: ergometric stress test; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions.

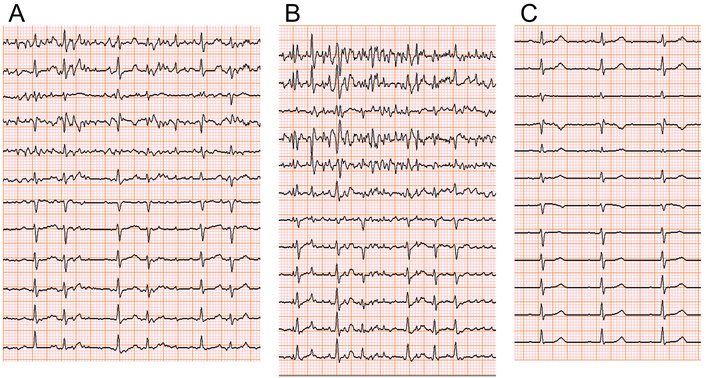

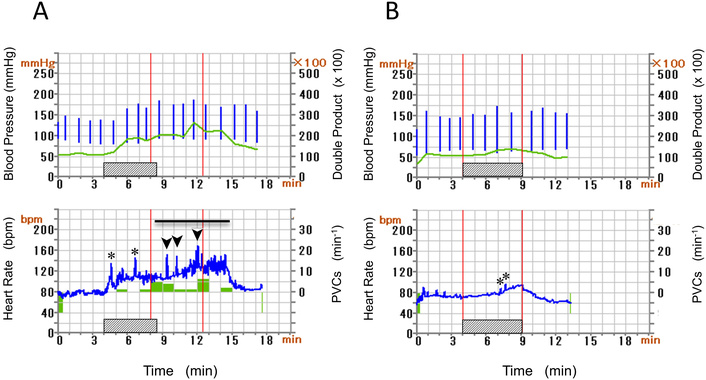

An 80-year-old woman (Case 1), a non-smoker, complained of palpitations. She had a history of heart failure (HF) and dyslipidemia, and diet therapy for salt and lipid restriction was recommended by another clinic. She was living alone with anxiety due to palpitations and hence referred to our hospital. Heart sounds and breath sounds were not particular. Chest X-ray showed borderline cardiomegaly, i.e., CTR was 50.9%. Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left atrial size (left atrial volume index of 25.5 mL/m2) and left ventricular contractility (left ventricular end-diastolic volume index of 37.9 mL/m2 and left ventricular ejection fraction of 58.1%). Serum chemistry showed no abnormalities except for NTproBNP of 533 (normally less than 55) pg/mL on admission. Ambulatory monitoring was performed based on the scientific statement of arrhythmia monitoring [3], which demonstrated frequent supraventricular premature contractions (SVPCs), and we performed a bicycle ergometric stress test (EST) to evaluate her exercise tolerance and inducibility of arrhythmia by exercise. SVPCs were observed prior to starting the exercise (Figure 1A) and increased with an augmentation of exercise workload. At the maximum level of exercise intensity, repetitive SVPCs converted to atrial fibrillation (AF). EST was terminated immediately after the onset of AF (Figure 1B). AF sometimes with a rapid ventricular rate sustained for several minutes in the post-exercise period and returned to sinus rhythm spontaneously (Figure 1C). Figure 2 indicates hemodynamics and arrhythmia records during EST. Heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) increased gradually according to an increase in the intensity of workload. Hence, the double product (DP) obtained by multiplying systolic BP by HR increased by EST but further increased in the post-exercise period. The post-exercise increase in DP disappeared with the conversion of AF to sinus rhythm. Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) increased (shaded histogram), and SVPCs and subsequent AF appeared during and after the exercise (Figure 2A). We prescribed her bisoprolol (2.5 mg per day), considering that exercise-induced AF may impair the quality of her life after discharge. EST at the same protocol was repeated two weeks after the first EST and before discharge to evaluate the effectiveness of bisoprolol. SVPCs were diminished, PVCs and AF were not induced, HR and BP were reduced throughout the secondary EST (Figure 2B). Her palpitation was considerably attenuated after discharge by continuing oral bisoprolol (2.5 mg per day).

Electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring during an ergometric stress test (EST) in an 80-year-old woman (Case 1). Supraventricular premature contractions (SVPCs) before starting EST (A) increased with EST. Atrial fibrillation (AF) in EST (B) disappeared several minutes after the EST (C).

Blood pressure (vertical bars) and double product were indicated (upper panel), whereas heart rate (HR) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) count (histogram) were shown (lower panel) before (A) and after (B) administration of bisoprolol (Case 1). Hatched bars indicate EST. Horizontal bar means AF. Spikes of increasing HR represent short runs of SVPCs (asterisks) and rapid AF (arrow heads). Post-exercise increase in double product (A) is not observed in (B). AF: atrial fibrillation; EST: ergometric stress test; SVPCs: supraventricular premature contractions.

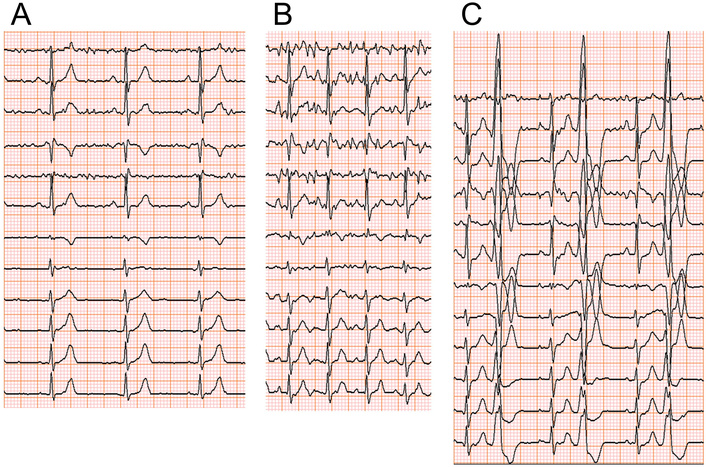

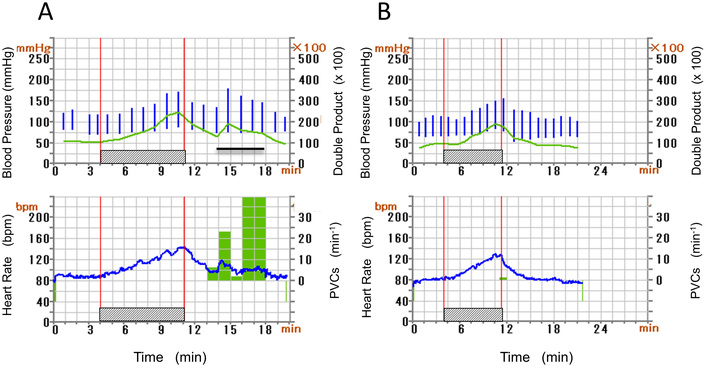

A 39-year-old woman (Case 2), a non-smoker, works in a hospital. She is slender and feels palpitations in the evening at the end of the day’s work. We found no particular abnormalities in physical findings and serum chemistry, i.e., NTproBNP was 53 pg/mL. Chest X-ray showed no specific abnormalities (CTR of 39.6%). Transthoracic echocardiography indicated no specific structural abnormalities. She underwent EST to investigate the cause of palpitations. She completed the exercise at the maximum intensity of 121 Watt and physical activity of 9.1 metabolic equivalents (METS). The electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor presented no arrhythmia before and during the exercise periods (Figures 3A–B). However, 2 minutes after terminating the EST, we observed PVCs with left bundle branch block and inferior-axis QRS morphology, which formed ventricular bigeminy lasting for 5 minutes (Figure 3C). Figure 4 indicates hemodynamics and arrhythmia records during EST. DP increased continuously during the exercise period and declined after the exercise. However, this product increased again, corresponding to the appearance of PVCs (Figure 4A). We diagnosed her palpitation with exercise-related frequent PVCs originating from the ventricular outflow tract (VOT). She has a history of oral intake of propranolol, a nonselective β-blocker, and discontinuation due to the adverse general fatigue. Based on the diagnosis and her history, we prescribed bisoprolol (2.5 mg per day), which ameliorated her palpitations in the evening on working days. After confirming the improvement of her symptoms, we repeated EST at the same protocol 2 weeks after starting the medication. The ECG monitor revealed no PVCs before and during the exercise, and we confirmed only one PVC after terminating the secondary EST (Figure 4B). Her palpitation in the evening was attenuated under the continuation of oral bisoprolol (2.5 mg per day).

ECG monitoring in a 39-year-old woman (Case 2). (A, B) No arrhythmia was recorded before and during EST. (C) PVCs appeared 2 minutes after terminating EST. Ventricular bigeminy lasted for 3 minutes during recovery time. ECG: electrocardiogram; EST: ergometric stress test; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions.

Hemodynamic parameters and arrhythmia count were the same as in Figures 2A–B indicated before and after starting bisoprolol (Case 2). Hatched bars indicate EST. PVCs after the exercise (A) are not observed in (B). Post-exercise increase in double product (A) corresponds to the repetitive PVCs (horizontal bar). The time scale in (B) differs from that in (A). EST: ergometric stress test; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions.

EST was essential for the diagnostics of the two cases and performed using Corival CEPT (Zernikepark 16, 9747 AN Groningen, Netherlands). BP monitoring and 12-lead digital ECG recording are completed by the optional equipment of Corival CEPT. ECG with a sampling frequency of 16 kHz for digital processing contains an intrinsic arrhythmia classification algorithm. Off-line ECG in EST was reviewed independently by a cardiologist. A couple of ESTs were performed at 15:00 with identical staff and settings and with an interval of 2 weeks in both cases. Baseline HR and BP were monitored in supine and then sitting positions. EST was staged and symptom-limited, i.e., the two patients began pedaling at a speed of 50 rounds per minute (rpm) throughout. After 4 minutes of warming-up, the intensity of cycling was increased by 15 Watt every minute to achieve an increase in energy expenditure of METS. The protocol of the progressive staged EST in each case was presented in Table 3, and the hemodynamics and arrhythmia records during ESTs performed with and without bisoprolol are presented in Table 4.

Protocol of the staged ergometric stress test.

| Cases series | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | ||||||||||

| Time (min) | rest | WU | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | recovery | ||

| Exercise intensity (Watt) | 0 | 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 75 | 0 | ||

| Physical activity (METS) | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 1.3 | ||

| Cycling speed (rpm) | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 0 | ||

| Case 2 | ||||||||||

| Time (min) | rest | WU | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | recovery |

| Exercise intensity (Watt) | 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 75 | 90 | 105 | 120 | 0 |

| Physical activity (METS) | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 1.5 |

| Cycling speed (rpm) | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

Exercise intensity was augmented every minute by 15 Watt. Upper and lower rows correspond to Case 1 and Case 2, respectively. METS: metabolic equivalents; rpm: rounds per minute; WU: warming-up period.

Summary of ergometric stress test in the two cases of exercise-related arrhythmia.

| Cases series | Case 1 (80-year-old woman) | Case 2 (39-year-old woman) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Bisoprolol treatment | Control | Bisoprolol treatment | |

| Protocol | 0 Watt–15 Watt | 15 Watt–15 Watt | ||

| THR (bpm) | 119 | 154 | ||

| Exercise time (min/s) | 4 min 25 s | 5 min 03 s | 7 min 04 s | 7 min 19 s |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 77 → 170* | 57 → 94 | 81 → 144 | 66 → 128 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 132/94 → 186/92 | 117/56 → 157/65 | 111/76 → 147/83 | 94/60 → 150/84 |

| Maximum performance (Watt) | 66 | 75 | 121 | 124 |

| Physical activity (METS) | 4.8 | 5.2 | 9.1 | 9.3 |

| Arrhythmia counts (SVPC/PVC) | 239/21 | 11/0 | 0/124 | 0/1 |

The interval of the paired ergometric stress tests is two weeks in both cases. Protocol means the combination of starting exercise intensity (Watt) and incremental exercise intensity (Watt). Heart rate (bpm) and blood pressure (mmHg) indicate the two values immediately before starting exercise and at the end of the exercise, respectively. *: Heart rate at the end of exercise was estimated under AF in Case 1. AF: atrial fibrillation; METS: metabolic equivalents; PVC: premature ventricular contraction; SVPC: supraventricular premature contraction; THR: target heart rate (bpm: beats per minute).

Both exercise-induced AF and post-exercise idiopathic PVCs are representative of exercise-related arrhythmia. Bisoprolol is a cardiospecific β-blocker and is used widely for tachyarrhythmias, including AF and idiopathic PVCs [4, 5]. A couple of ESTs indicate that bisoprolol is associated with reduced susceptibility to arrhythmia to exercise. The common findings of the two cases following bisoprolol administration are two-fold, i.e., (1) a possible increase in exercise time, physical activity, and maximum performance was noted, and (2) an abnormal post-exercise increase in DP disappeared after starting bisoprolol. This abnormal post-exercise hemodynamics is unfavorable, limiting exercise tolerance. It is conflicting to use DP as a surrogate for the direct measure of oxygen consumption (VO2). This situation has allowed the proposal of many formulae predicting the maximum VO2. Although some of them are not necessarily validated across all generations, the current prediction model becomes more precise when adding circulatory and respiratory variables in a large cohort [6]. Further study is required to validate whether the effectiveness of bisoprolol on exercise-related arrhythmia is linked to the improved post-exercise hemodynamics.

Exercise-related arrhythmia is a potential medical and social problem in active people regardless of age. Bicycle ergometry is widely performed in patients with exercise-related arrhythmia to evaluate exercise tolerance, risk stratification, and therapeutic response to antiarrhythmic strategies. The two cases presented here showed the representative exercise-related arrhythmia, i.e., exercise-induced AF and exercise-related PVCs arising from VOT [1].

Case 1 showed AF at the maximum intensity of control EST. AF is sometimes induced by exercise in patients with HF, as in this case. Endurance exercise impacts all three elements (substrate, triggers, and modulating factors) of Coumel’s “arrhythmia triangle” [7], i.e., substrate is the arrhythmogenic atrium in HF patients, atrial high pressure and dilatation modulate atrial conduction and refractoriness, and strenuous exercise triggers SVPCs leading to AF [8, 9]. Bisoprolol is a highly selective β1-blocker and is administered in AF patients not only for rate-control but also for suppression of AF [10, 11], which is mediated partly by the ameliorated hemodynamics of HF by bisoprolol.

Case 2 showed PVCs in the immediate post-exercise period. Based on literature discriminating right from left VOT origin of PVCs by surface ECG [12, 13], this case shows frequent PVCs arising from right VOT, the most common focus of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmia in apparently healthy subjects. Right VOT shows complicated arrhythmogenic substrates characterized by distinct developmental origins and unique cellular and molecular mechanisms [14, 15], implying suppressive actions of β-blockers on the triggered electrical activity of right VOT [4, 5, 16]. The complicated interplay of exercise-modulated neurohumoral factors and electrophysiological alterations may have maximized the arrhythmogenicity of right VOT in the immediate post-exercise period [17]. Considering the interval of prescriptions of propranolol and bisoprolol, it is unlikely that prior propranolol influenced the effects of bisoprolol on the exercise-related PVCs.

Susceptibility of the atria to AF and VOT to PVCs may have been attenuated by bisoprolol in these cases, which is presumably mediated by altered neuro-humoral influence, improved hemodynamics, and cardiac ion channel remodeling reported in the third-generation β1-blocker [18]. DP at the final stage of EST is decreased, and post-exercise increase in DP is not observed under the bisoprolol treatment (Figures 2 and 4). These may have led to the favorable outcome (Table 4). Exercise capacity altered by β-blocker is controversial, i.e., β1 selectivity and intrinsic sympathomimetic activity differ among β-blockers, β1-receptor polymorphism relates to the different sensitivity to β-blockers, and exercise-induced β2-mediated airway dilatation influences the exercise capacity [19–22]. Bisoprolol does not suppress β2-mediated bronchodilation during exercise in therapeutic use [23]. Reportedly, the favorable effects of carvedilol and bisoprolol on exercise capacity are based on the improved cardiac metabolism by sparing high-energy phosphates [24], while another study revealed that bisoprolol showed reduced peak VO2 but no improvement in exercise capacity in HF patients [25].

This study has several limitations. First, we documented only two cases and did not include control subjects. Second, we adopted a simple ergometric test without direct VO2 measurement or objective imaging and could not confirm DP as a reliable VO2 surrogate. Ideally, an improved exercise tolerance by bisoprolol should be confirmed by direct VO2 measurement using a cardiopulmonary exercise test in a large sample. Although this report primarily describes short-term effects of bisoprolol on exercise-related arrhythmias, the long-term suppression of such arrhythmias is required in daily life and leisure-time sports. Furthermore, this study reporting two cases did not allow a placebo-controlled crossover design. A couple of ESTs in a non-blind manner may have allowed for the day-to-day variability, learning effects, or an increase in the intrinsic exercise tolerance.

Exercise-related arrhythmia is problematic because of the increased popularity of leisure-time sports. Symptom-limited graded bicycle ergometry was performed to investigate the hemodynamic correlates and the effectiveness of bisoprolol in exercise-related arrhythmia. A couple of bicycle ergometry for comparison of arrhythmic behaviors with and without treatment provides a therapeutic strategy in exercise-related arrhythmia. Arrhythmia suppression and improved physical activity were observed following bisoprolol treatment in two cases of different types of exercise-related arrhythmia. Antiarrhythmic effects of bisoprolol may cause favorable post-exercise hemodynamic responses, leading to the possibility of improved exercise tolerance. We should reconfirm this conclusion in large sample studies.

AF: atrial fibrillation

BP: blood pressure

DP: double product

ECG: electrocardiogram

EST: ergometric stress test

HF: heart failure

HR: heart rate

METS: metabolic equivalents

PVCs: premature ventricular contractions

SVPCs: supraventricular premature contractions

VO2: oxygen consumption

VOT: ventricular outflow tract

All authors acknowledge the nursing, laboratory, and rehabilitation staff taking care of the participants described.

TM: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. YY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. MH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Internal Ethics Committee under the condition of secure personal data protection and compliance with privacy policy, because the examinations and treatment of two cases were followed strictly by the Regulation of Japanese Healthcare Insurance.

Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from participants and guardians.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from participants and guardians.

The datasets of this manuscript could be available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request to Toru Maruyama (tmaruyama@haradoi-hospital.com).

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 860

Download: 54

Times Cited: 0

Wollner Materko ... Carlos Alberto Machado de Oliveira Figueira