Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

Email: islam1048@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4855-6226

Affiliation:

2Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-1502-1714

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2943-6404

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-1171-0783

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3892-4494

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0160, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4058-026X

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2026;6:1004137 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2026.1004137

Received: November 01, 2025 Accepted: January 15, 2026 Published: January 27, 2026

Academic Editor: Guoku Hu, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China

The article belongs to the special issue Breakthroughs in Mechanisms and Treatments for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and ischemic stroke cause progressive and often irreversible neuronal loss, leading to major functional disability. Conventional pharmacological therapies primarily offer symptomatic relief and fail to promote neuro-restoration. Stem cell-derived exosomes have recently gained attention as acellular, regenerative biologics capable of modulating inflammation, enhancing synaptic repair, and facilitating neural recovery. These nanoscale vesicles carry bioactive molecules, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and growth factors, that replicate many of the paracrine benefits of stem cells without the associated risks of tumorigenicity or immune rejection. The objective of this review is to critically evaluate recent evidence on the neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, and translational mechanisms of stem cell-derived exosomes in major neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders, highlighting their clinical relevance and therapeutic potential. Preclinical studies suggest that exosome administration may restore mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and support neuronal survival, with associated improvements in cognitive and motor outcomes in experimental models of AD, PD, and stroke. Exosomal miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-124, and miR-133b mediate neuroprotective effects through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling, while miR-146a promotes immunomodulation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and facilitating microglial repair phenotypes. Early-phase clinical studies primarily demonstrate feasibility and short-term safety, with exploratory signals of neurological improvement that require confirmation in adequately powered trials. Despite challenges in standardization and regulation, exosome-based therapy represents a scalable, safe, and clinically translatable strategy for neuro-regeneration, with significant promise for future management of brain network disorders.

Neurodegeneration is characterized by the progressive loss of neuronal structure and synaptic integrity within the central nervous system (CNS), driven by converging mechanisms such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, abnormal protein aggregation, and chronic neuroinflammation. Mitochondrial impairment leads to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), increased endogenous antioxidant defenses that result in lipid peroxidation, protein instability, and DNA damage, eventually triggering neuronal apoptosis. In parallel, pathological protein aggregates, including amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, and α-synuclein (α-syn), activate microglia and astrocytes, resulting in inflammatory cascades that exacerbate synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss [1, 2]. The proposed interactions that have been shown to remain over time that render certain CNS disorders persistent.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and ischemic stroke are the most prevalent neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders and together impose a substantial global burden of morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic cost. AD accounts for the majority of dementia cases, PD incidence continues to rise with aging populations, and ischemic stroke remains a leading cause of long-term neurological disability worldwide [3–5]. This growing disease burden underscores the urgent need for therapeutic strategies that extend beyond symptomatic control.

Current clinical treatments for these disorders are largely palliative and do not address the underlying neuronal loss. Pharmacological therapies for dementia, including cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, provide modest and time-limited symptomatic benefit. Similarly, dopaminergic therapies in PD temporarily alleviate motor symptoms without halting disease progression. In acute ischemic stroke, reperfusion strategies such as thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy reduce acute neuronal necrosis but do not promote neural regeneration or long-term circuit repair [6, 7]. Consequently, there is increasing interest in regenerative approaches capable of restoring neural function and modulating pathological neuroinflammation.

Stem cell-based therapies have emerged as a promising regenerative strategy due to their multipotent differentiation capacity, trophic support, and immunomodulatory properties. However, clinical translation has been hindered by significant challenges, including tumorigenicity, immune rejection, poor cell survival, and ethical concerns [7]. In this context, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic strategy. These nanosized extracellular vesicles (EVs; 30–150 nm) transport bioactive proteins, lipids, and RNAs that may have parent-cell effects. Crucially, they can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), provide neuroprotection, modulate immune responses, and enhance synaptic plasticity while avoiding the risks of live cell transplantation [8, 9].

This review provides an integrative analysis of stem cell-derived exosomes as a clinically translatable, cell-free platform for neuro-regeneration and immunomodulation, highlighting their mechanistic basis, bioengineering advances, and key translational challenges. We critically evaluate their potential as a safe and scalable alternative to conventional stem cell transplantation in neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders.

Exosomes are tiny (~30–150 nm) EVs that are released by the endosomal pathway. Specifically, intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are released as exosomes when multivesicular bodies (MVBs) fuse with the plasma membrane. Their origin, size, and cargo are different from those of other EVs: microvesicles, also known as ectosomes, bud directly from the plasma membrane and are larger (approximately 100–1,000 nm), whereas apoptotic bodies, which are produced during cell death and frequently contain organelles, nuclear fragments, and generally more heterogeneous debris, are still larger (approximately 0.5–2 µm) [10, 11].

Exosome biogenesis occurs through both endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms. In the ESCRT pathway, ESCRT-0 recognizes ubiquitinated cargos, ESCRT-I and II help with membrane deformation and cargo clustering, and ESCRT-III mediates membrane scission of inward budding ILVs; accessory proteins such as vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4 (VPS4) aid in complex disassembly. ESCRT-independent ILV formation is mediated by lipid rafts, ceramide, sphingomyelin, neutral sphingomyelinases, and tetraspanin-enriched microdomains. Rab GTPases coordinate vesicle trafficking, with Rab5 and Rab7 driving endosomal maturation and Rab27a/b regulating MVB transport, docking, and exosome release. Tetraspanins such as CD9, CD63, CD81, and CD82 function as both biomarkers and active regulators by facilitating cargo sorting, modifying the lipid microenvironment, and influencing exosome targeting and cellular uptake [12–14].

Exosomes are enriched in heat shock proteins (HSPs; HSP70, HSP90, HSP60), ESCRT-associated proteins [tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein (TSG101), Alix], Rab GTPases, annexins, flotillins, integrins, and tetraspanins, while lacking many organelle-derived proteins such as apoptotic bodies. Their lipid bilayer is comparatively rigid due to high sphingomyelin, cholesterol, ceramide, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylcholine content. Exosomal RNA cargo includes mRNAs and short noncoding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs) (e.g., miR-21, miR-124, miR-133b, miR-125a), which are enriched and functionally active in gene regulation [15, 16].

When stem-cell-derived exosomes are released, target cells in the CNS, such as neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, may take them up through a variety of mechanisms such as endocytosis, receptor binding, and fusion, sending signals that regulate survival, differentiation, inflammation, and plasticity. In one study, MSC-derived exosomes enhanced angiogenesis and endothelial repair by transferring functional miRNAs, including miR-125a and miR-21/let-7c-5p, as demonstrated in endothelial cells and stressed HUVEC models in vitro [16–18].

MSC-derived exosomes are well characterized for immunomodulatory and angiogenic actions, including suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, T-cell modulation, and induction of anti-inflammatory mediators. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived exosomes provide patient-specific regenerative signals and exhibit organ-protective effects, such as improved survival and reduced fibrosis, partly mediated by miRNA clusters such as miR-106a-363 [19–23]. Refer to Figure 1 for a schematic flowchart of the process of exosome biogenesis, cargo sorting, and release from stem cells.

Exosomes produced from stem cells work through interrelated neuroprotective, regenerative, and immunomodulatory pathways to provide therapeutic benefits. These vesicles transport bioactive cargo, mostly miRNAs, proteins, and lipids, which influence apoptosis, oxidative stress, synaptic remodeling, and immunological activation in the CNS [24]. An important mechanism is the activation of pro-survival signaling cascades such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), which improve neuronal viability, prevent caspase (Cas)-mediated apoptosis, and promote mitochondrial integrity [24, 25]. Exosomal miRNAs work by binding their seed region to complementary sites in target mRNAs’ 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs), resulting in translational suppression and/or mRNA instability. For example, miR-21, one of the most abundant exosomal miRNAs found in MSC-exosomes, binds to conserved regions in the 3′-UTR of PTEN and PDCD4, reducing their expression and relieving inhibitory control over the PI3K/Akt pathway and apoptotic regulators. Loss of PTEN activity raises PIP3 levels and Akt phosphorylation, favoring neuronal survival, growth, and mitochondrial stability; PDCD4 suppression prevents Cas cascade activation and apoptosis [26]. Similarly, miR-124 contributes to anti-inflammatory microglial polarization and neurite outgrowth through the regulation of inflammatory and cytoskeletal pathways. These interactions were validated in vitro by reporter assays and in vivo by target knockdown and pathway activation. Exosomal miR-21 and miR-124 suppress pro-apoptotic genes such as PTEN, PDCD4, promoting cell survival through PI3K/Akt signaling [24, 27]. These effects work together to preserve neuronal membrane integrity and prevent oxidative damage following an ischemic or degenerative insult.

Exosomes also aid in neuro-restoration by increasing synaptic plasticity, axonal regeneration, and neurogenesis. Enriched miRNAs, such as miR-124, miR-9, and miR-133b, influence Rho-GTPase signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling, increasing dendritic spine density and synaptic connection [28–33]. Exosomal transfer of trophic and angiogenic substances such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) promotes neuronal and endothelial proliferation, which improves cerebral perfusion and tissue healing [30, 31, 34]. These processes are responsible for functional improvements in cognitive and motor performance shown in preclinical models of AD, PD, and ischemic stroke [5–9, 35–37].

Exosomes generated from stem cells also have immunomodulatory characteristics. Exosomes transport miRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-124, which decrease nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation. This shifts microglia from pro-inflammatory M1 to reparative M2 phenotypes and reduces cytokine output [37–39]. They additionally minimize astrocytic reactivity and glial scar formation while increasing regulatory T-cell (Treg) expansion and inhibiting cytotoxic T-cell infiltration, resulting in an anti-inflammatory environment that promotes neuronal regeneration [40–42]. These pathways can reduce neuroinflammation and neuronal loss caused by α-syn and Aβ in certain diseases, including PD and AD [43–45].

Stem cell-derived exosomes cause a multifactorial neurotherapeutic response that integrates cellular protection with network-level recovery across a wide range of neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders by bringing together anti-apoptotic, antioxidative, pro-regenerative, and immunoregulatory pathways. The major molecular mediators and downstream signaling pathways involved in exosome-mediated neuroprotection and immunomodulation are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Mechanisms of exosome-mediated neuroprotection and regeneration.

| Mechanistic category | Molecular mediators | Primary target/effect | Downstream signaling pathway | Functional outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-apoptotic | miR-21, miR-124, Bcl-2 | Inhibits PTEN, PDCD4 | PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK | ↑ Cell survival, ↓ caspase activity |

| Antioxidant | miR-199a-5p, HO-1, NQO1 | Stabilizes Nrf2 | Nrf2/HO-1 signaling | ↓ ROS, ↓ lipid peroxidation |

| Synaptic plasticity | miR-124, miR-9 | Remodels dendritic spines | Rho-GTPase modulation | ↑ Synaptogenesis, ↑ LTP |

| Angiogenesis | miR-125a, VEGF | Endothelial proliferation | PI3K/Akt and ERK | ↑ Cerebral perfusion |

| Axonal regeneration | miR-133b, GAP-43 | Promotes axonal sprouting | ERK/CREB, STAT3 | ↑ Motor recovery |

| Immunomodulation | miR-146a, miR-124 | Microglial M1 → M2 shift | NF-κB inhibition | ↓ TNF-α, ↓ IL-6, ↓ IL-1β |

| BBB integrity | MCP-1, VEGF, miR-21 | Enhances astrocyte function | PI3K/Akt | ↓ BBB leakage, ↑ tight junctions |

Akt: protein kinase B; BBB: blood-brain barrier; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IL: interleukin; miRNA: microRNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; LTP: long-term potentiation; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase.

Immunomodulatory effects of stem cell-derived exosomes in neuroinflammation.

| Immune target | Exosomal cargo | Effect on immune cell | Experimental context | Functional outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia | miR-146a, miR-124 | Shifts phenotype from M1 → M2 | Stroke, PD models | ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines, ↑ trophic activity |

| Astrocytes | miR-21, miR-124 | ↓ GFAP, ↓ glial scar | Spinal cord injury, ischemia | ↑ Neurite regeneration |

| T cells | Surface ligands, miR-155 inhibitors | ↑ Treg proliferation, ↓ cytotoxic T-cell infiltration | Autoimmune & injury models | ↓ Peripheral inflammation |

| Systemic cytokines | Exosomal miRNAs | ↓ IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 | Multiple CNS disorders | ↓ Neuroinflammation, ↑ repair environment |

| Peripheral macrophages | Exosomal proteins (Annexin-A1, Alix) | Modulate antigen presentation | MCAO and PD models | ↓ Microglial activation |

CNS: central nervous system; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion; miRNA: microRNA; PD: Parkinson’s disease; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; IL: interleukin; Treg: regulatory T-cell.

In an animal model of preclinical AD using MSC-derived exosomes, robust neuroprotective effects were observed in preclinical models. MSC-derived exosomes significantly reduced the Aβ plaque burden and significantly increased synaptic plasticity by delivering neprilysin and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), which degrade the Aβ neurotoxic peptides, preventing the neurotoxic accumulation [1]. MSC-derived exosomes improve mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and reduce astrocytic and microglial activation, thereby limiting cortical and hippocampal neuroinflammation. Several studies also report preservation of cholinergic neurotransmission in AD, suggesting coordinated modulation of neuronal networks and synaptic function [2].

In addition, MSC exosomes also modulate major signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt and ERK to grant neuronal survival and synaptic maintenance. Exosomes derived from iPSCs have been shown to provide similar facilitatory functions via miR-29c, which is involved in the regulation of β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), which controls the primary enzymatic pathway of Aβ production [3]. More specifically, Aβ processing decreases plaque deposition, maintains stability of dendritic spines and long-term potentiation (LTP). In preclinical studies, repeated iterative delivery of exosomes, through intranasal and intravenous routes, restored cognitive deficits, learning, memory, and enhanced neurogenesis, especially in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus [4]. Therefore, in summary, exosomes can target multiple processes at once, like influencing amyloid metabolism, synaptic preservation, anti-oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and stabilizing mitochondria as the mechanistic basis of AD pathology in AD. Refer to Table 3 for a summary of preclinical evidence for stem cell-derived exosomes in major neurodegenerative disorders.

Summary of preclinical evidence for stem cell-derived exosomes in major neurodegenerative disorders.

| Disease | Exosome source | Key cargo (miRNAs/proteins) | Mechanistic pathway(s) | Experimental model | Outcome/Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–4] | MSC | miR-21, miR-29c, IDE, neprilysin | ↓ Aβ aggregation, ↑ synaptic plasticity, activation of PI3K/Akt, and ERK pathways | Transgenic APP/PS1 mice | Reduced Aβ plaque load, improved memory, restored mitochondrial function |

| iPSC | miR-29c | ↓ BACE1 activity, ↑ LTP, dendritic spine stability | APP/PS1 and in vitro neuronal models | Improved cognitive scores | |

| NSC | miR-124, BDNF | ↑ Neurogenesis, ↓ astrocytic reactivity | Aβ-induced cell cultures | Reduced neuroinflammation | |

| Parkinson’s disease (PD) [5–7, 43–45] | MSC | miR-133b, catalase, SOD | ↑ Neurite outgrowth, ↓ α-syn, antioxidative protection | 6-OHDA, MPTP mouse models | Restored dopaminergic signaling, improved motor behavior |

| NSC | miR-124, miR-146a | Inhibited microglial activation, NF-κB modulation | α-Syn overexpression models | ↓ Inflammatory cytokines, ↑ neuronal survival | |

| Ischemic stroke [3, 8, 9, 37, 46] | MSC | miR-21, miR-124, VEGF, BDNF | ↑ Angiogenesis, ↑ neurogenesis, activation of PI3K/Akt & MAPK/ERK | MCAO rat/mouse models | ↓ Infarct volume, ↑ motor recovery |

| Hypoxia-primed MSC | miR-146a, miR-199a | ↑ Anti-inflammatory potential, ↓ apoptosis | Post-ischemic rodent models | Improved sensorimotor recovery |

Akt: protein kinase B; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; NSC: neural stem cell; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; α-syn: α-synuclein; 6-OHDA: 6-hydroxydopamine; Aβ: amyloid-β; BACE1: β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IDE: insulin-degrading enzyme; LTP: long-term potentiation; miRNA: microRNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase.

In PD models, MSC-derived exosomes enriched with miR-133b mediated neurite outgrowth and neuronal differentiation and shared synapse regenerative properties with pertinent dopaminergic neurons [5]. These exosomes increased striatal dopamine levels and dopaminergic activity, and modalities that developed motor behavioral function and coordination. These observations align with established antioxidative and immunomodulatory mechanisms of stem cell-derived exosomes described earlier [6]. Behaviorally, the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) and MPTP PD models exhibited impressive locomotion, balance, limb use, and additional exploratory behaviors with exosome treatment, demonstrating functional improvement in experimental models [7].

Ischemic stroke rodent studies, exosomes from MSCs decreased infarction volume, induced angiogenesis, and neurogenesis in peri-infarct areas [8]. Exosomal cargo supports angiogenesis and neuronal repair through conserved pro-survival signaling pathways previously outlined [9]. Interestingly, preconditioning MSC treatment against hypoxic or cytokine-treated conditions via exosomes increased their anti-inflammatory potential in terms of functional recovery, degree of apoptosis, and sensorimotor function [46].

Exosomal interventions can be delivered intravenously, intranasally, and intracerebrally. In particular, intranasal administration provides direct access to the CNS, and intravenous control assessment allows for systemic administration to the patient [47]. Optimal dosing, frequency, and treatment duration remain unresolved, and standardized protocols are needed. Exosome heterogeneity driven by source, preparation, and storage limits reproducibility and consistency [48]. Robust characterization methods such as nanoparticle tracking analysis, proteomics, and RNA profiling are therefore essential for quality control and clinical translation [49].

Currently, the translational pathway from pre-clinical to human use is underway, with clinical trials already initiated. A Phase I/II trial (NCT03384433) is evaluating intravenously administered MSC-derived exosomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke, with primary endpoints focused on safety, tolerability, and adverse immune responses. While exploratory neurological and functional outcomes are being assessed, the study is not powered to establish efficacy [46]. Preliminary reports indicate acceptable safety profiles and no significant immune-related adverse events; however, these studies were not designed or powered to assess clinical efficacy, supporting clinical trial feasibility in acute stroke. Cognitive recovery trials indicate exosomes may confer greater neurological than motor benefits. An early-phase clinical trial evaluating iPSC-derived exosomes in AD (NCT04388982) is primarily focused on safety, tolerability, and biomarker modulation rather than clinical cognitive efficacy, with the goals of reducing amyloid deposition, improving cognitive function, and reduce neuroinflammation [47].

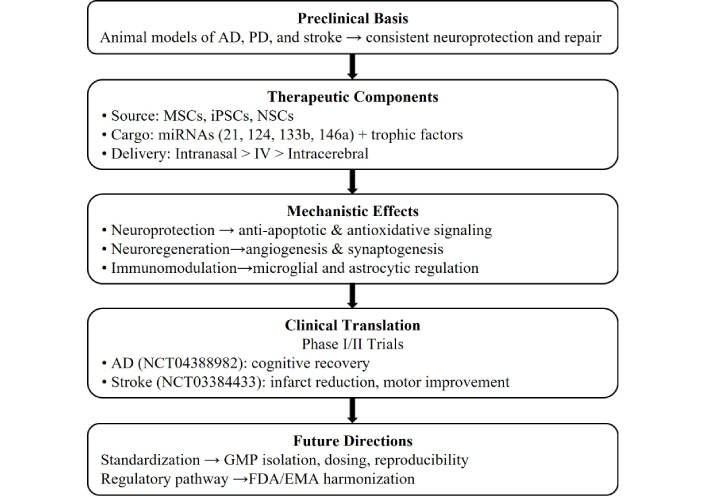

Preclinical studies have shown that cyclic administration may induce synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and reduced oxidative stress, all of which could represent potential mechanisms for clinical use. Stem-cell-derived exosome trials are basically just extensions of putative mechanisms of action in human subjects; clinical trials demonstrate advancing exosome-based therapies to be used in a clinical context. Refer to Figure 2 for a schematic diagram of the translational framework of neuro-regeneration.

From stem cell-derived exosomes to clinical neuroregeneration: translational framework.

Exosomes offer distinct advantages for stem cells. Exosomes are non-replicating, which reduces any chance of tumorigenicity or ectopic differentiation [48]. Exosomes are also acellular, which greatly simplifies their storage, standardization, and bulk Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-production capabilities for potential “off-the-shelf” therapeutic applications. Furthermore, ethical and immunological barriers are significantly less problematic than with living cell-based therapies, and they also provide safety against immune rejection and avoid risks associated with uncontrolled cellular proliferation [48, 49]. Because of their nanoscale size, exosomes also afford more homogenous tissue infiltration and cellular uptake/targeting of the target cells than whole stem cells. Refer to Table 4 for a summary of the comparative advantages and limitations of emerging neurotherapeutic modalities.

Comparative advantages and limitations of emerging neurotherapeutic modalities.

| Therapeutic modality | Key advantages | Key limitations | Clinical suitability/use-case in CNS disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem cell transplantation |

|

|

|

| Stem cell-derived exosomes |

|

|

|

| Gene editing (CRISPR, base editors, prime editing) |

|

|

|

| Small molecule drugs |

|

|

|

BBB: blood-brain barrier; CNS: central nervous system; CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; PK/PD: pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; SMA: spinal muscular atrophy; Cas: caspase; miRNA: microRNA.

Delivery to the CNS is challenging. The intranasal route uses olfactory and trigeminal pathways that bypass the BBB for immediate access to cortical and hippocampal sites [49]. However, it suffers from variable dosing, muco-ciliary clearance, limited volume per nostril, and uncertain distribution to deep brain structures. Intravenous administration results in rapid systemic clearance and sequestration in the liver/spleen. Intracerebral/intraventricular delivery achieves high local concentrations but is invasive and less suitable for chronic therapy. In addition, surface-engineered exosomes with peptides or ligands (RVG29, transferrin) increase neuronal intake and target cell specificity [50]. Pharmacokinetic studies show rapid systemic clearance with some CNS retention, allowing potential local therapeutic effects. Strategies like hydrogels and nanoparticles are being explored to extend retention, protect cargo, and enhance bioavailability, while considerations include ligand design, immunogenicity, biodistribution, and GMP-scale production [51]. Overcoming these challenges will require standardized assays for targeting efficacy, comparative biodistribution studies in large animals, and early dialogue with regulators on acceptable modifications for clinical translation.

Despite encouraging preclinical and early translational findings, the evidence base for stem cell-derived exosomes as neurotherapeutic agents is still limited and varied. The majority of published studies use small animal models, which have limited external validity and inconsistent methodology [24, 25, 30, 32]. Human research, while emerging, frequently involves small cohorts, lacks proper control arms, and varies greatly in follow-up duration [37–39]. Furthermore, the technological variation in exosome isolation, spanning from ultracentrifugation and polymer precipitation to microfluidic approaches, results in significant variability in particle yield, purity, and bioactive cargo composition [11, 12]. Analytical methods such as nanoparticle tracking analysis, transmission electron microscopy, and exosomal marker immunoblotting (CD9, CD63, TSG101) are used inconsistently, confounding cross-study comparison [10, 11, 41]. Many studies also prioritize surrogate biochemical endpoints over standardized behavioral or neurophysiological outcomes [26, 28, 37].

Despite these limitations, convergent preclinical findings support biological plausibility, although methodological heterogeneity limits definitive conclusions [24, 26, 28, 30]. Exosome treatment, unlike stem cell transplantation, eliminates the dangers of tumorigenicity, immunological rejection, and ectopic differentiation while allowing for scalable, GMP-compliant manufacture [9, 10, 40, 41]. Nonetheless, the lack of standardized techniques and poor long-term safety evidence remain significant hurdles to clinical translation [11, 12, 37–39]. Future research should focus on multicenter randomized controlled trials, standardized exosome characterization frameworks, and well-defined pharmacokinetic and dose-response investigations to demonstrate efficacy, repeatability, and safety in clinical populations [10–12, 37, 38, 42]. Figure 3 illustrates a standardized workflow for exosome isolation and characterization to improve reproducibility based on the minimal information for studies of EVs 2018 (MISEV2018) principles with specific, practical steps.

A number of challenges still remain, even with hopeful outcomes. The challenges for bulk quantities of high-purity content are extremely logistically difficult; there are variable yield and reproducibility outcomes with methodologies to isolate exosomes, like ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, and microfluidic methods [52]. There are also regulatory classification variances throughout different jurisdictions that can influence the potential approval paths for exosome-based therapeutic agents [53]. Regulatory agencies currently treat exosome products within existing biologics/ATMP frameworks, requiring evidence of identity, purity, potency, and safety; however, classification and requirements differ by jurisdiction and are evolving. Major regulatory hurdles include: defining a consistent product (heterogeneous cargo), establishing validated potency assays, demonstrating manufacturability under GMP, and proving long-term safety [54].

Ethically, first-in-human trials must balance potential benefit against uncertain long-term risks and ensure informed consent explicitly covers unknowns such as genomic regulation and off-target effects. To address the lack of long-term safety data, we recommend: (1) registry-style long-term follow-up (5–10+ years) for all trial participants to capture late adverse events, (2) standardization of biodistribution and tumorigenicity testing in relevant large-animal models, (3) adoption of risk-based regulatory pathways that require staged escalation (pilot safety cohorts to randomized trials), (4) independent data safety monitoring boards, and centralized reporting of adverse events. Regulators and researchers are increasingly proposing a risk-based classification of bioengineered EVs in order to adjust requirements for surface-modified or cargo-loaded exosomes [54, 55].

Lastly, the circulatory half-life may be short, which may shorten therapeutic durations and would require repeated dosing of sustained-release formulations to enhance exosome delivery to the biopsy location. Emerging evidence indicates that physicochemical stimulation of biocompatible scaffolds can markedly promote neural differentiation, neurogenesis, and synaptic network formation. These strategies include near-infrared and visible-light photo-stimulation, thermal and electrical cues, chemical surface functionalization, topographical guidance, and photocatalytic activation, often facilitated by graphene-based or other two-dimensional nanomaterial scaffolds. Such stimuli regulate stem cell fate by modulating intracellular signaling, membrane polarization, and cytoskeletal organization [56, 57]. Notably, these physicochemical approaches are mechanistically complementary to exosome-mediated delivery of bioactive cargo, suggesting that combined scaffold stimulation and exosome therapy may synergistically enhance neuronal maturation, connectivity, and functional recovery. Integrating these multimodal bioengineering strategies offers a more comprehensive framework for advancing exosome-based neuro-regenerative therapies [58].

Furthermore, the electrically conductive properties of advanced biomaterial scaffolds, such as three-dimensional rolled graphene oxide foams, have been shown to enhance neural fiber growth through electrical stimulation–mediated activation of stem cells [59]. In parallel, stem cell-derived exosomes promote neurogenesis and axonal regeneration via activation of intracellular signaling cascades, notably the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. The convergence of these bioelectrical and molecular mechanisms suggests a synergistic therapeutic strategy, whereby conductive scaffolds may potentiate exosome-mediated signaling to optimize neural repair and functional recovery [60]. This combinatorial approach highlights the potential of integrating exosome-based therapies with bioengineered conductive platforms to enhance regenerative outcomes in neurological disorders.

Continued optimization of manufacturing, dosing, and delivery methodology, and appropriate preclinical validation will be necessary for safe, reproducible, and clinically effective neuro-regenerative interventions [51–53].

miRNAs exhibit inherent biological promiscuity, as a single miRNA can partially bind multiple mRNA targets across diverse pathways, creating a risk of off-target effects [61]. In the context of exosome-based therapies, this raises concerns regarding dysregulated cell proliferation, such as miR-21 in certain oncogenic settings, unintended immunomodulation, suppression of tumor-regulatory pathways such as PTEN/PDCD4, and effects on non-neural tissues following systemic distribution [61, 62]. The complexity of exosomal cargo further complicates predictability, as co-delivered RNAs and proteins may interact synergistically or antagonistically to alter overall biological output. Mitigating these risks requires careful target validation, controlled dosing, tissue-directed delivery strategies, and thorough preclinical safety evaluation to ensure therapeutic specificity and long-term safety [61–63].

Stem cell-derived exosomes provide a novel therapeutic frontier in neurodegeneration by integrating regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant mechanisms within a non-cellular, biocompatible platform. Accumulating preclinical evidence demonstrates their ability to attenuate neuroinflammation, preserve mitochondrial and synaptic integrity, and promote functional recovery across major neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disorders, including AD, PD, and ischemic stroke. Compared with direct stem cell transplantation, exosomes offer superior safety, scalability, BBB penetration, and engineering flexibility, positioning them as clinically attractive biologics. However, meaningful translation will depend on resolving key challenges related to cargo heterogeneity, standardized manufacturing, potency assays, dosing, and long-term safety, particularly regarding miRNA-mediated off-target effects. Continued advances in bioengineering, targeted delivery strategies, and regulatory harmonization are expected to facilitate the clinical translation of exosome-based therapies. With rigorous standardization of manufacturing processes and validation through adequately powered clinical trials, stem cell-derived exosomes may help address the current gap between symptomatic management and regenerative strategies.

3′-UTRs: 3′-untranslated regions

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

Akt: protein kinase B

Aβ: amyloid-β

BBB: blood-brain barrier

BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Cas: caspase

CNS: central nervous system

ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase

ESCRT: endosomal sorting complex required for transport

EVs: extracellular vesicles

GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein

GMP: Good Manufacturing Practice

HSPs: heat shock proteins

IL: interleukin

ILVs: intraluminal vesicles

iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell

MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase

MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion

miRNAs: microRNAs

MISEV2018: minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018

MSC: mesenchymal stem cell

MVBs: multivesicular bodies

NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate

Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

NSC: neural stem cell

PD: Parkinson’s disease

PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase

ROS: reactive oxygen species

STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

TNF: tumor necrosis factor

TSG101: tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein

VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor

VPS4: vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4

α-syn: α-synuclein

AWI: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ZKR: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. HSW: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. BS: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SH: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SRK: Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1139

Download: 21

Times Cited: 0

Ningyun Hu ... Rong Ma