Affiliation:

1Polytechnic University of Coimbra, Lagar dos Cortiços, S. Martinho do Bispo, 3045-093 Coimbra, Portugal

2H&TRC-Health & Technology Research Center, Coimbra Health School, Polytechnic University of Coimbra, 3045-043 Coimbra, Portugal

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-4826-6922

Affiliation:

1Polytechnic University of Coimbra, Lagar dos Cortiços, S. Martinho do Bispo, 3045-093 Coimbra, Portugal

2H&TRC-Health & Technology Research Center, Coimbra Health School, Polytechnic University of Coimbra, 3045-043 Coimbra, Portugal

3Research Center for Natural Resources, Environment and Society (CERNAS), Polytechnic University of Coimbra, Bencanta, 3045-601 Coimbra, Portugal

4MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre/ARNET-Aquatic Research Network, University of Coimbra, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal

Email: valado@estesc.ipc.pt

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0157-6648

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2026;6:1004138 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2026.1004138

Received: September 21, 2025 Accepted: January 14, 2026 Published: February 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Shile Huang, Louisiana State University Health Science Center, USA

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease affecting the central nervous system, the cause of which remains unknown. Environmental, genetic, and immunological factors are considered risk factors. MS has no cure; therefore, therapy focuses on reducing the number of outbreaks, controlling symptoms, and therapies aimed at modifying the course of the disease. Innovative strategies that promote remyelination and repair of damaged brain tissue are under investigation. This review aims to compile and systematize the available knowledge on the multifactorial nature of MS, highlighting the main risk factors. It also discusses the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of the disease, current therapies, and prospects, presenting a comprehensive overview of the effect of various drugs on remyelination and repair of central nervous system damage.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search, guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards, was conducted across PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify relevant clinical trials. Of the studies retrieved, 13 were selected for this review. These trials specifically explored integrated therapeutic approaches, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, for managing MS.

Results: The results reflect the multifactorial nature of MS and the existence of several promising therapies to combat inflammation and demyelination, as well as to promote remyelination. Reducing inflammation remains the main target, but new approaches such as clemastine, liothyronine, interleukin (IL)-2, N-acetylglucosamine, and intracranial transplantation of fetal human neural precursor cells have shown promising results.

Discussion: Currently, the therapies available for MS target the peripheral immune system. Therefore, more studies are needed on treatment therapies that combine immunomodulation of the peripheral and central nervous systems to reduce the neurological disability of patients. It is also concluded that the therapies were safe and were well tolerated, given the occurrence of a small number of adverse events.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by demyelination and axonal destruction, involving genetic, immunological, and environmental factors [1, 2].

It affects around 2.8 million people and is more prevalent in temperate climates, with more than 200 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [3, 4]. The incidence increases with latitude and is twice as common among women, possibly due to genetic and hormonal factors [3].

In Portugal, the prevalence is 64 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [5], with variations: Santarém with 46.3 cases, Lisbon with 41.4 cases [6], Braga with 39.8 cases, Entre Douro e Vouga with 64.4 cases [5, 7], and Coimbra with 143.45 cases [5].

The etiology is still unknown [8], but factors such as low sun exposure, reduced vitamin D levels, and infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are considered risk factors [1, 9]. A higher prevalence is associated with lower sun exposure, resulting in low levels of vitamin D, which is crucial for reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines [1].

EBV causes a persistent infection of B cells, a subset of lymphocytes characterized by the expression of immunoglobulin receptors, which enable them to recognize specific antigens. This recognition facilitates the humoral immune response by presenting antigens to T cells and inducing the production of antibodies [10, 11]. The molecular mimicry between the EBV antigen and the myelin basic protein (MBP) epitope can cause an autoimmune response against the CNS. Infection in adolescence or adulthood doubles the risk of MS, while in childhood it appears to confer protection [9].

Different alleles of human leukocyte antigens, namely the HLA DRB1*1501-DQB1*0602 haplotype, are associated with an increased risk of MS by facilitating the presentation of autoantigens to T cells, promoting inflammation [12].

Changes in the gut microbiome, such as a reduction in Prevotella and Adlercreutzia, can trigger autoimmune responses due to the mimicry of CNS autoantigens [2]. Prevotella promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Adlercreutzia metabolizes phytoestrogens, and its reduction is associated with increased oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). In models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the transfer of intestinal microbiota from patients promoted the spontaneous and more severe development of EAE [13].

Glatiramer acetate, an EAE inducer, is immunomodulatory and has been approved as a first-line drug for treating RRMS. It is thought to reduce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and stimulate the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting a bidirectional interaction between the microbiome and the immune system [13].

Although the microbiome is considered a potential biomarker, it is still unclear whether the changes are the cause or consequence of the disease [2].

Genetic defects in regulatory T cells allow effector T cells to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and attack oligodendrocytes (OLs), leading to demyelination [12]. Auto-reactive T cells stimulate B cells to produce antibodies that cross the damaged area of the BBB, intensifying myelin destruction and inflammation [8].

Phenotypically, MS is classified as RRMS and progressive MS (PMS), subdivided into secondary PMS (SPMS) and primary PMS (PPMS). Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is a single episode of demyelination lasting at least 24 hours. Radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) refers to the presence of demyelinating lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [14, 15] (Figure 1).

Active lesions show abundant inflammatory infiltrates, including macrophages, microglia, astrocytes, and lymphocytes. Chronic active lesions present reduced cellularity, whereas chronic inactive lesions are characterized mainly by reactive astrocytes. Slowly expanding lesions (SEL) share cellular features with chronic lesions.

RRMS involves acute episodes of demyelination with partial recovery and stability. SPMS presents constant neurological deterioration, without sudden attacks, and is always preceded by RRMS [8]. Advanced age, a higher number of relapses, and spinal cord involvement accelerate progression. PPMS, which is less common, manifests progression from the outset, with rapid motor disability, and it is unclear whether it is a distinct entity from SPMS [14].

The diagnosis is based on clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings [12], following McDonald’s criteria [8, 14], which include clinically typical syndrome, evidence of CNS lesions, dissemination in space and time, and exclusion of other causes. MRI and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis are the main diagnostic methods [14].

The gold standard laboratory test detects oligoclonal IgG bands in CSF resulting from antibody production [12, 16], suggesting an active immune response [14]. The presence of these bands in CSF, but not in serum, is not specific to MS, as other inflammatory pathologies may also present them [12, 14].

Once diagnosed, the degree of disability must be assessed and quantified using Kurtzke’s expanded disability status scale (EDSS) based on neurological examination and describing the signs and symptoms in eight functional systems: pyramidal, cerebellar, brainstem, visual, sensory, visceral, and bladder, among others [17, 18]. The score ranges from 0 (normal neurological examination) to 10.0 (death due to MS). Scores between 0 and 4.5 are determined by the functional systems, meaning that in this range, the patient is fully ambulatory. A range of 5.0 to 6.5, ambulatory function and the need for assistance with locomotion is considered. Scores between 7.0 and 10 are characterized by the inability to perform daily activities until death [18]. The EDSS is the most widely used measure for assessing disability progression and neurological changes, but it is limited by observer subjectivity and uneven phenotype distribution across the scale [17] (Figure 2).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), namely miR-199a (protective effect) and miR-320 (pathogenic effect), are biomarkers of the pathophysiology and prognosis of MS [19].

Neurofilament light chain (NfL) released after CNS injury reflects axonal damage and inflammatory activity in RRMS [16, 20]. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) indicates astrogliosis, astrocytic damage, and progression in SPMS. Elevated levels are due to increased cell membrane permeability and pathological response to injury. In CSF, parvalbumin is associated with cortical neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. Because it is also expressed in muscle fibers, its usefulness as a biomarker is limited [20].

Protein 1, like chitinase-3 associated with astroglial and microglial reactivity, is elevated in advanced stages of the disease, accelerating the conversion from SCI to RRMS and indicating resistance to interferon (IFN)-β therapy [16, 21].

Currently, MS has no cure [13], so treatment focuses on managing flare-ups, disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), and symptom relief [8, 13].

Corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, treat acute relapses by inhibiting the activation of inflammatory cytokines and the migration of immune cells to the CNS [8].

DMTs reduce flare-ups and delay progression, being most effective in RRMS [22]. Among the drugs approved by the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drug Administration, IFN-β and glatiramer acetate [23] stand out, as well as oral therapies such as dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, and teriflunomide [8].

Fingolimod prevents lymphocyte infiltration into the CNS. Teriflunomide inhibits the proliferation of autoreactive lymphocytes by blocking pyrimidine synthesis. Dimethyl fumarate activates the erythroid-derived nuclear factor type 2 pathway, combining immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects with a mechanism still under investigation [22, 23].

For PMS, therapies such as siponimod, ocrelizumab, and cladribine are indicated in active cases. In PPMS, ocrelizumab is the only approved therapy [23, 24].

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, such as evobrutinib, tolebrutinib, and fenebrutinib, aim to reduce inflammation and neurodegeneration by acting on the periphery and the CNS [24]. Several strategies that promote remyelination or repair of damaged brain tissue are being investigated [8].

The CNS is a compact structure composed of neurons and glial cells with essential functions in supporting and maintaining neuronal activity [15].

Advances in microscopy and staining techniques have made it possible to classify glial cells into three types: astrocytes, microglia, and OL. Later, OPCs were identified and classified as the fourth type of glial cell present in the brain [15].

Microglia are essential for CNS homeostasis, contributing to neuronal development, synaptic plasticity, and myelin regulation, while continuously monitoring the brain microenvironment through their branched morphology. However, in the presence of tissue damage or inflammation, migration and activation of microglia cells to the damaged area occur. When this activation occurs persistently, it contributes to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [25].

The plasticity of microglia allows their polarization into different activation phenotypes, classified as M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) [26]. Phenotype M1 is characterized by the production of inflammatory mediators and reactive species such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-12, IL-23, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), nitric oxide, as well as CD68, major histocompatibility complex class II molecules, receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulins, and integrins. The permanent activation of this phenotype amplifies the inflammatory response [27]. On the other hand, the M2 phenotype is associated with the resolution of inflammation and tissue repair through the release of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 and increased expression of CD206 and arginase-1 [25] (Figure 3).

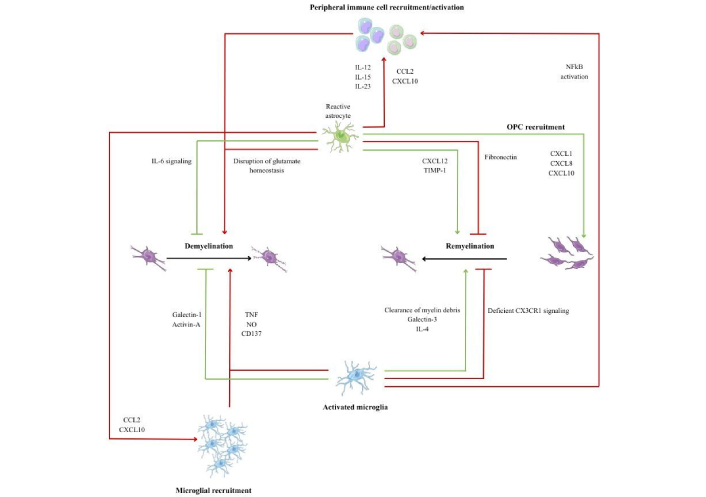

Microglia-astrocyte-OPC interactions during demyelination and remyelination. Created with Canva. Reactive astrocytes and activated microglia exert harmful (red) and beneficial (green) effects on lesion evolution, modulating inflammation, myelin debris removal, and OPC recruitment and differentiation, thus allowing a balance between demyelination and remyelination. CCL2: C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; CX3CR1: C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1; CXCL: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; IL: interleukin; NFkB: nuclear factor kappa B; NO: nitric oxide; OPC: oligodendrocyte precursor cell; TIMP: tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

In the EAE models, the predominance of the M1 phenotype is observed in early stages of MS, while the M2 phenotype becomes more prevalent in late phases, promoting the differentiation of OLs and remyelination. This evidence the functional plasticity of microglia [28].

However, currently, the M1/M2 paradigm is considered reductive. Transcriptomic studies demonstrated that microglial activation is not restricted to two stages, but rather to a continuous spectrum of phenotypes dependent on the context, stimulus, and brain region involved [29].

The persistence of pro-inflammatory microglial states, associated with Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and sustained production of inflammatory cytokines, contributes to chronic inflammation and progression of neuroaxonal injury. In contrast, pro-regenerative microglial phenotypes, involved in the effective removal of myelin debris, are scarce in chronic MS lesions. At the same time, OPCs have a reduced ability to respond to differentiation signals due to aging, metabolic dysfunction, and mitochondrial alterations, making them more vulnerable to a persistent inflammatory microenvironment. Pathological remodeling of the extracellular matrix, with increased tissue stiffness and accumulation of sulfated proteoglycans, also constitutes a barrier to OPC migration and maturation. Together, these mechanisms explain the failure of remyelination, especially in progressive stages of the disease, due to the interaction between persistent microglial inflammation, functionally compromised OPCs, and a hostile lesion microenvironment [30–32].

OPCs are progenitor cells of the CNS that, when activated, proliferate, migrate to the lesion, and differentiate into mature OL. These are responsible for the production of myelin sheaths in demyelinated axons, which is crucial for the efficient transmission of nerve signals [33].

There are several factors that can either promote or hinder the activation of OPCs. Among the factors that promote their activation are insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of OPCs, and platelet-derived growth factor, which is essential for recruiting OPCs to the lesion. Fibroblast growth factor promotes proliferation, but when in excess, it can inhibit OL differentiation. In addition, C-X-C chemokine 12 helps attract OPCs to demyelinated areas, facilitating regeneration. Another set of factors that promote OPC activation are molecules released by pro-regenerative microglia and macrophages. Noteworthy are transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which promotes OPC differentiation, activin-A, which stimulates OL maturation, and galectin-3, which facilitates OPC migration to the lesion, contributing to myelin repair [34] (Figure 3).

A chronic inflammatory environment, characterized by the presence of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, can block OPC differentiation and prevent the formation of new myelin sheaths. In addition, pro-inflammatory microglia and macrophages release signals that inhibit regeneration. Myelin debris contains differentiation inhibitors, namely hyaluronic acid and CD44, and their accumulation hinders the maturation of OL. Ageing exacerbates this scenario, as it reduces the response of OPCs to growth factors and compromises the ability to remyelinate. Advanced age and changes in cellular metabolism contribute to making regeneration less efficient, further exacerbating the impact of demyelinating lesions [34] (Figure 3).

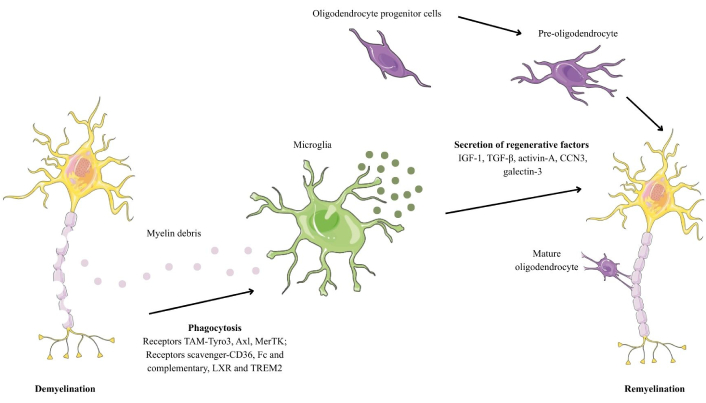

The differentiation of OPCs into fully mature OL and myelin producers is divided into four stages: proliferative OPCs, immature OPCs (pre-OLs), differentiated OL, and myelinating OL [15] (Figure 4).

Demyelination and subsequent remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Created with Canva. CCN3: cellular communication network factor 3; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1; LXR: liver X receptor; MerTK: myeloid-epithelial-reproductive tyrosine kinase; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; TREM2: triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2.

OPCs are characterized by high expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFR-α) and neuron/glia antigen 2 (NG2), which are essential for migration and proliferation processes. OPCs evolve into pre-OLs, they begin to lose their bipolar morphology and start to form myelin sheaths around the axons. At this stage, they begin to express 2´,3´-cyclic nucleotide 3´-phosphodiesterase (CNPase), O4, and O1. With maturation, mature OL acquire the ability to produce multiple concentric layers of myelin around axons, which is essential for the efficient conduction of nerve impulses. At this stage, they express myelin-specific proteins, such as MBP and the transcription factor Olig2, which is unique to mature OL [33].

The interaction between axons and OL capable of producing myelin is regulated by ion channels located at the junction between myelin and axons. The intracellular calcium concentration in OL, including in the myelin sheaths, directly influences the formation and remodeling of myelin [35].

In addition to the predominant role of OL in myelination, they play an essential role in the metabolic support of axons by supplying lactate. It is used by axons to produce mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate. This metabolic interaction ensures the efficient transmission of nerve impulses [15].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a common feature in both immune system cells and OL of the CNS in patients with MS. Impaired mitochondrial function leads to energy deficits that affect nerve impulse transmission and axonal transport, ultimately contributing to neurodegeneration. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the production of reactive oxygen species, exacerbating myelin damage and inflammation [15, 35]. Associated with axonal damage, NfL is released into the interstitial space and subsequently reaches the CSF and peripheral blood. NfL concentration has been shown to correlate directly with relapses and disease progression and is widely used in clinical trials [35].

Together, changes in glucose metabolism affect energy supply, which is essential for OL function and myelin production. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism alters the composition of myelin and affects its stability and integrity. In MS, OL become dysfunctional, and nerve impulse transmission is compromised, leading to demyelination and axonal degeneration. When demyelination spreads through the tissue, microglia and inflammatory cells are recruited to remove myelin debris and combat the adverse environment [15].

Initially, it was believed that the immune response was harmful because it intensified glial scarring and exacerbated lesions. However, it is now known that immune function is essential for the repair process of lesions in the CNS. Nevertheless, in humans, this process results in the formation of chronic scar tissue consisting of hypertrophied astrocytes with no metabolic capacity or function [34].

CNS lesions are often accompanied by rupture of the BBB, leading to the extravasation of serum components such as thrombin and fibrinogen. In this way, circulating antibodies can reach the brain and aggravate the lesion [36].

To prevent damage to the CNS, an inflammatory cascade is activated that involves the local activation of microglia and astrocytes, thereby initiating the secretion of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and chemokines. These increase vascular permeability and the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, facilitating the recruitment of leukocytes to the CNS. This inflammatory response is crucial for restoring homeostasis and protecting the CNS from further injury [37].

Reactive astrocytes play a crucial role in this process by forming dense margins around the injury area, limiting the spread of inflammation and cytotoxic molecules. These cells also contribute to the formation of the extracellular matrix, creating a dense network that makes up the glial scar. However, this structure contains molecules that inhibit axon growth, namely chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan, semaphorins, and ephrins. As these lesions tend to be prolonged, the scarring response can evolve into fibrosis, hindering tissue repair processes [38].

Although glial scar formation can be beneficial in areas of the brain with low regenerative capacity by isolating damaged areas and preventing further injury, the situation is different in demyelinating diseases. In MS, axons are largely preserved, but the myelin sheath that surrounds them is damaged. Thus, an exacerbated scarring response interferes with the remyelination process. Since axons are still functional, the priority should be to promote myelin regeneration rather than create barriers that inhibit this process [37].

Remyelination is a spontaneous regenerative process that occurs after the loss of myelin around an intact axon and involves coating that same axon with a new, shorter, and thinner myelin sheath, resulting in slower conduction of the action potential [35].

Failure to remyelinate can lead to the formation of areas of chronic demyelination, characterized by a decrease in the number of remyelinated axons and the presence of astrocytic scars [37].

MS lesions are characterized by the relative preservation of axons. These lesions have a central vein, from which the inflammatory reaction and extravasation of serum components arise [39]. The inflammatory infiltrate consists of macrophages, proliferating microglia, and, to a lesser extent, CD8+, CD4+, and B lymphocytes [40]. These initial lesions are densely populated by myeloid cells, which are crucial for the removal of myelin debris [41].

Despite the unfavorable environment for remyelination in the CNS, it is possible for this to occur. When this happens, shadow plaques form, clearly defined areas characterized by fewer myelinated axonal fibers with thinner than normal myelin sheaths. Remyelination varies significantly between patients, but tends to be more active in the early stages of MS. However, it is common for areas of demyelination and remyelination to coexist in the same lesion, indicating repeated episodes of damage and repair [37].

The presence of OPCs in chronic lesions, even in small quantities, suggests that the failure of remyelination may be due to a blockage in the differentiation of these cells, possibly due to an unfavorable lesion microenvironment [42]. Inflammation, gliosis, and extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronic acid, CD44, semaphorins, and versican are associated with failure to remyelinate [37].

Myeloid cells play an essential role in CNS remyelination. The first mechanism involves the identification of damage to myelin through PRRs that detect the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and DAMPs. These receptors include a family of transmembrane proteins located on the cell surface or in endosomes and include TLRs, C-type lectin receptors, as well as RIG-I-type receptors and NOD-type receptors of cytoplasmic proteins. Demyelinating lesions in MS release DAMP, which include heat shock proteins, high mobility group protein 1, uric acid, adenosine triphosphate, lipids, and hydrophobic myelin proteins. The sudden exposure of the hydrophobic part of these components acts as an alarm signal, indicating that tissue damage has occurred. When PRRs recognize myelin DAMP, they activate inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB) pathway, which induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the IFN pathway, which modulates the immune response [34].

Once activated, myeloid cells can adopt a protective and pro-remyelinating role by removing myelin debris and releasing neuroprotective factors such as IGF-1 and TGF-β, stimulating OL differentiation. On the other hand, if the inflammatory process is prolonged, myeloid cells maintain a chronic pro-inflammatory state, releasing cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, which inhibit OL differentiation. In this way, they contribute to the formation of glial and fibrous scars and prevent remyelination [34].

The second mechanism involves the TREM2, which recognizes the anionic lipids released by apoptotic bodies and is present in myelin debris [43].

TREM2, together with TLRs, can act as a detection and signaling system for damaged myelin. However, it is not yet known how these systems interact, whether in different cells and at different sites of injury, or simultaneously in the same cell type. Previous studies have shown that TLR and TREM2-dependent pro-inflammatory activation of myeloid cells is essential for remyelination [44].

Despite advances, challenges remain in accurately understanding the role of different myeloid cell populations. One of the main challenges is the functional and phenotypic distinction between monocyte-derived macrophages and activated resident microglia. Macrophages tend to appear early in toxin-induced demyelinating lesions but are quickly outnumbered by microglia [45].

Effective elimination of damaged myelin is critical to limiting the extent of tissue damage and initiating repair. Damaged myelin becomes non-functional, and debris that accumulates in the extracellular space impedes OPC recruitment and differentiation [37].

First, myelin debris is recognized by the PRRs of myeloid cells. Among the main receptors involved in this process are TAM receptors [Tyro3, Axl, myeloid-epithelial-reproductive tyrosine kinase (MerTK)], which recognize phosphatidylserine, facilitating phagocytosis [46]; scavenger receptors (CD36, Fc, and complementary) that assist in the ingestion of debris after it has been opsonized by antibodies or complement; and TREM2, responsible for detecting myelin lipids and activating microglia to remove debris [34, 47] (Figure 4).

After recognition, phagocytosis of the residues occurs through endocytosis, fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes to degrade myelin into reusable components, and, finally, the metabolic conversion of ingested myelin [34].

This process is essential, given that myelin is rich in high amounts of cholesterol and phospholipids that need to be recycled properly. In this way, myelin residues are transported to the endoplasmic reticulum, where cholesterol can be stored or eliminated [48]. The liver X receptor (LXR) pathway is activated to promote cholesterol efflux and prevent lipid toxicity. Metabolic changes in both macrophages and microglia determine whether the environment will be pro-inflammatory or pro-regenerative [34].

However, with advancing age, the ability to activate the receptors involved in phagocytosis decreases, reducing the effectiveness of elimination. The accumulation of debris can inhibit OPC migration and block remyelination. When microglia or macrophages are in a chronic pro-inflammatory state, they produce toxic cytokines that aggravate the lesion [34].

Currently, drugs are available that target the peripheral immune mechanisms of MS, thereby reducing relapses. As these therapies do not act on CNS inflammation, their effectiveness in PMS remains quite limited. However, drugs that act to prevent the progressive accumulation of neurological disability and promote repair have not yet been developed [33, 34].

One promising therapeutic approach involves the use of drugs capable of modulating the immune response in such a way that acute inflammatory lesions are stimulated to remyelinate, thereby preventing progression to chronic lesions. However, these drugs have a narrow therapeutic window, as they are most effective in acute inflammatory lesions. Nevertheless, it was only at the beginning of the 21st century that it was recognized that remyelination and other regenerative processes depend on the occurrence of inflammation. In MS, remyelination is compromised, which contributes to the progression of the disease to the progressive phase. Thus, there is a need to develop therapies aimed at restoring remyelination [34].

In the early stages of the disease, remyelination can be successful due to the residual presence of OL and their progenitors. However, as MS progresses, there is a decrease in the number of neurons, OL, and OPC, which, together with the inflammatory environment, potentiate the failure of remyelination [15].

Several clinical trials have been conducted using drugs to promote OPC differentiation, based on the assumption that the blockage in the differentiation of these cells is the main reason for the failure of remyelination in MS. Some of these drugs act by modulating specific receptors in the CNS, including muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (namely the M1 subtype) and histamine receptors (H1 and H3). Among these drugs, benzotropine, clemastine, quetiapine, ivermectin, and GSK239512 stand out [15, 33].

Although some trials have shown efficacy, the results have not been good enough to be considered effective remyelination therapies. This is because the blockage in OPC differentiation does not occur uniformly in all lesions and in all patients. Without a way to stratify patients who are likely to respond to therapy, there is a risk of underestimating the results. In animal models, it has been found that with ageing, OPCs lose their sensitivity to differentiation inducers. This suggests that increased efficacy can be achieved through the simultaneous administration of a cellular rejuvenating agent, such as metformin [49].

Current therapeutic approaches focus on stimulating OPCs and tend to disregard the inhibitory factors of the lesion microenvironment, especially the inflammatory signals that prevent myelin regeneration. However, a more in-depth study of the relationship between inflammation and remyelination may contribute to the development of more effective treatments [34].

Macrophages and microglia can either promote or inhibit this process, depending on their functional stage. Efficient removal of myelin debris is crucial for OPC differentiation. One strategy to improve this process involves the use of niacin (vitamin B3), known to increase CD36 receptor expression, promoting phagocytosis of myelin debris by macrophages and microglia [50].

Conjointly, factors derived from immune cells that directly regulate OPC differentiation have been identified. Notable among these are macrophage-derived activin-A and regulatory T cell-derived cellular communication network factor 3 (CCN3), which act to promote the formation of new OL [51].

Activation of the LXR nuclear receptor through stimulation with LXR agonists promotes the elimination of myelin debris and remyelination through the efflux of cholesterol from microglia and macrophages. Cholesterol is an essential constituent for the synthesis of new myelin sheaths. This process promotes an increase in desmosterol, the precursor of cholesterol that activates LXR, inducing a change in the inflammatory profile to one more favorable to remyelination [48].

Opicinumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of leucine-rich repeat protein 1 (LINGO-1), a glycoprotein found on the surface of neurons and OL, that negatively regulates OPC differentiation, myelination, and axonal regeneration. In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that blocking LINGO-1 allows axons to remyelinate [33].

However, the clinical failure of opicinumab highlights a fundamental limitation of remyelination strategies that target a single target in MS. Although LINGO-1 is a negative regulator of OPC differentiation, mechanistic evidence indicates that antibody binding alone is insufficient to achieve functional target engagement and induce the conformational and signaling changes required for human OPC differentiation. In chronic lesions, where aged OPCs, persistent microglial inflammation, and extracellular matrix remodeling impose additional barriers to remyelination, this change is more pronounced. These findings suggest that the failure of remyelination in MS is not driven by a single molecular mechanism, but rather by a simultaneous network of inhibitory mechanisms that cannot be overcome through the isolated use of LINGO-1 [52].

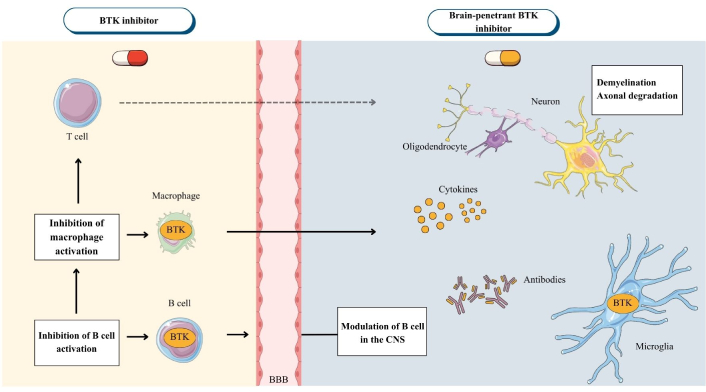

To reduce intrinsic CNS inflammation, BTK inhibitors expressed in hematopoietic cells, including tolebrutinib [53], and ibudilast [54], are in clinical trial phases and have shown promising effects [53].

BTK inhibition exerts distinct but complementary immunomodulatory effects on B cells and myeloid cells in the CNS by attenuating B-cell receptor-mediated signaling and reducing inflammatory cytokine production without inducing cell depletion. Simultaneously, drugs such as tolebrutinib, which can penetrate the CNS, directly inhibit BTK in microglia, attenuating compartmentalized inflammation that contributes to axonal damage and remyelination failure [55] (Figure 5).

Mechanism of action of BTK inhibitors in multiple sclerosis. Created with Canva. Peripherally acting BTK inhibitors reduce B-cell activation and proliferation, as well as myeloid cell activation, which contributes to a reduction in inflammation and the frequency of flares. However, they are unable to modulate compartmentalized inflammation in the CNS. In contrast, CNS-penetrant BTK inhibitors cross the BBB and directly inhibit B cell signaling and microglia activation, decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathological phagocytosis in lesions, central mechanisms that create a microenvironment hostile to OPC differentiation and remyelination. The scheme highlights that blocking peripheral inflammation prevents further damage but is insufficient to restore myelin repair without direct action in the CNS. BBB: blood-brain barrier; BTK: Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CNS: central nervous system; OPC: oligodendrocyte precursor cell.

Cell therapies offer a distinct approach by introducing exogenous stem cells, mesenchymal cells, and OPCs with the ability to differentiate into OL and directly regenerate damaged myelin. Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches, with some focusing on modulating inflammation and others on replacing affected cell niches [15].

This literature review-based project aims to gather and systematize the available knowledge on the multifactorial nature of MS, focusing on the main genetic, environmental, and immunological risk factors that influence the development and progression of the disease. It also aims to discuss the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of the disease, as well as current therapies and future prospects.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Protocol ID = CRD420251075078).

The literature search was conducted between October 2024 and May 2025 using search engines such as PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrial.gov, covering articles published between 2016 and 2025.

Keywords such as “multiple sclerosis”, “multifactorial”, “therapy”, “inflammation”, and “remyelination” were used, as well as the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: Multiple sclerosis (MeSH Unique ID: D009103), Inflammation (MeSH Unique ID: D007249), Remyelination (MeSH Unique ID: D000074586) and Therapy (MeSH Unique ID: Q000628).

Table 1 provides a detailed description of the search strategy, outlining the combination of MeSH terms with Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT) to retrieve the most relevant literature for analysis.

Search strategy used to obtain the clinical trials included in this review was combining the MeSH terms (“Multiple sclerosis”, “Inflammation”, “Remyelination”, and “Therapy”) with Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT).

| MeSH terms | Boolean operators | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AND | OR | NOT | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Inflammation, remyelination | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | Inflammation | Remyelination | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Inflammation, therapy | Remyelination | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Remyelination, therapy | ||

MeSH: Medical Subject Headings.

All articles were identified, selected, and analyzed based on previously established inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria aim to ensure that only articles with relevant information are included in the study. Full-text articles were included in this review, specifically reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical trials, all of which were free of charge and written in English or Portuguese. They were published within the last nine years, with the aim of exploring new findings about the multifactorial nature of this pathology. On the other hand, exclusion criteria included repeated articles, restricted-access articles, articles that deviated from the topics to be addressed, studies with a high risk of bias, and studies with incomplete data.

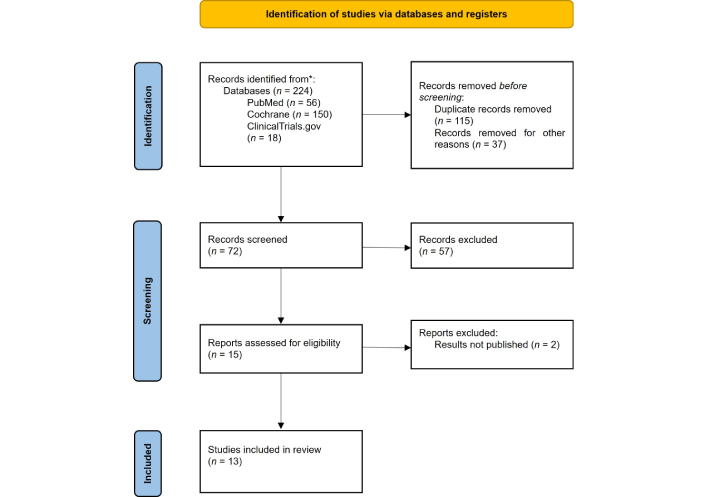

The selection of articles was carried out in two phases. Initially, the title and abstract were read and analyzed to select the articles relevant for a more detailed and in-depth reading. Next, the selected articles were read in full to confirm their relevance and extract all relevant data. This process is represented schematically in the PRISMA 2020 diagram [56] (Figure 6).

PRISMA 2020 diagram, including the number of articles evaluated, excluded, and included in this systematic review. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Adapted from [56]. © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. CC BY.

After applying the criteria, 13 articles were included in this review (Figure 6).

Data extraction included information such as authors, year of publication, study design, clinical form of MS, sample size, type of therapy, mechanism of action, and efficacy in clinical trials.

The risk of bias in the studies included in this systematic review was assessed using the Robvis (Risk-Of-Bias VISualisation) tool (RoB 2). This is a widely used tool for assessing the quality and potential for bias in scientific studies. For non-randomized or open studies, the ROBINS-I tool was applied. For randomized studies, the RoB 2.0 tool was applied.

Current treatments for MS focus mainly on the peripheral immune system. Therefore, a therapeutic approach that combines immunomodulation of the peripheral nervous system with that of the CNS could contribute to reducing inflammation and neurodegeneration, helping to prevent the increase in disability observed in patients with MS.

Clinical trials are divided into four phases with distinct objectives. Phase I, which is not therapeutic, aims to assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. Phase II studies evaluate efficacy, optimal dose, and short-term safety in patients with the condition under study. Phase III aims to confirm the therapeutic benefit needed to obtain marketing authorization. Finally, phase IV, once the drug has been introduced on the market, monitors long-term safety and drug interactions and provides marketing support [57].

This review included 13 studies that combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies as therapeutic options in patients with MS, as described in Table 2.

Systematization of studies included in this review demonstrates the effect of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies on MS.

| Study | Type of study | Population | Objective | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold et al. [58], 2018 | Phase IIa | 20 adults aged between 18 and 55 years old; with active RRMS (McDonald criteria 2010) and EDSS not exceeding 6.0 | To assess whether raltegravir can reduce the inflammatory activity of RRMS, as measured by active lesions in the brain detected by gadolinium-enhanced MRI. | Raltegravir did not reduce the number of active brain lesions compared to the pre-treatment period. There were no significant improvements in markers of inflammation, disability, and quality of life. |

| Soiza et al. [59], 2018 | Substudy of phase III trials (OPERA I and II) | 103 adults aged between 18 and 55 years: 59 patients with RRMS (McDonald criteria 2010) and EDSS: 0.0–5.5 and 44 healthy individuals | Compare brain volume loss in patients with RRMS treated with ocrelizumab with volume loss in healthy individuals. Assess whether suppression of inflammation with ocrelizumab reduces the rate of neurodegeneration to levels similar to those seen in normal aging. | Patients treated with ocrelizumab had brain volume loss rates similar to those of healthy controls. Patients treated with IFN-β-1a had higher rates of loss. The thalamus was the region with the greatest loss in both healthy individuals and patients. |

| Zurmati and Khan [55], 2023 | Phase IIb | 130 patients aged between 18 and 55 years old, with RRMS or SPMS (McDonald criteria 2017) and EDSS ≤ 5.5 | To determine the dose-response relationship between tolebrutinib and the reduction of new active brain lesions in patients with RRMS and SPMS. | Tolebrutinib significantly reduced inflammation in patients with RRMS. The 60 mg dose showed the best results. |

| Hartung et al. [60], 2022 | Phase IIb and extension | 270 patients aged between 18 and 55 years old; with RRMS (McDonald criteria 2010) and EDSS < 6.0 | Evaluate whether temelimab is effective and safe for treating patients with RRMS. | Temelimab had no effect on reducing acute inflammation, but showed radiological signs of possible antineurodegenerative effects, supporting its development for MS. |

| Kolind et al. [61], 2022 | Substudy of the phase III trial (OPERA II) | 78 participants: 29 patients treated with ocrelizumab, 26 patients treated with IFN-β-1a, and 23 healthy individuals | To evaluate the myelin water fraction in patients with RRMS treated with IFN-β-1a and those treated with ocrelizumab for 2 years (double-blind period), followed by an open-label extension of years of treatment with ocrelizumab. | Ocrelizumab prevents demyelination in white matter and chronic lesions when compared to IFN-β-1a. Some areas of the brain have shown that ocrelizumab can create a more favorable environment for remyelination in damaged tissue. |

| Abdelhak et al. [62], 2022 | Samples from the ReBUILD trial (phase II) | 50 patients with stable RRMS, in which only samples from 34 patients (24 women and 9 men) were analyzed | To assess whether treatment with clemastine fumarate (an antihistamine with remyelinating potential) reduces blood levels of NfL in patients with RRMS without disease progression. | Treatment with clemastine fumarate was associated with a reduction in blood NfL levels, suggesting neuroprotective effects through therapeutic remyelination. |

| Talbot et al. [63], 2022 | Exploratory analysis of data collected from a phase II trial | 120 participants aged between 18 and 65 years: 59 patients with PPMS (24 women and 35 men), 40 patients with RRMS according to the 2017 McDonald criteria (30 women and 10 men) and 21 healthy individuals (11 women and 10 men) | To study the relationship between inflammatory biomarkers in CSF and tissue damage in PPMS. | There is inflammation in the CNS, but this does not appear to be the main cause of brain damage. This may explain why therapies that target inflammation have less significant effects on this form of the disease. Associations with biomarkers of neuroaxonal damage and demyelination were weak, and there were no associations with MRI metrics. |

| Sy et al. [64], 2023 | Open-label, mechanistic phase clinical trial with dose escalation | 34 patients aged between 18 and 75 years old, with RRMS, SPMS or PPMS and taking glatiramer acetate for at least 3 months | To evaluate the effects of N-acetylglucosamine in patients with MS, specifically whether it has the ability to reduce markers of inflammation and neurodegeneration and its safety, as well as possible benefits in neurological function. | Oral N-acetylglucosamine reduced markers of inflammation and neurodegeneration in patients with MS, despite simultaneous immunomodulation by glatiramer acetate. |

| Newsome et al. [65], 2023 | Phase Ib | 20 adults (11 women and 9 men) aged between 18 and 58 years with RRMS (12 adults) or PPMS (8 adults) (McDonald criteria 2010) and EDSS: 3.0–7.5 | To evaluate the safety and tolerability of liothyronine in increasing doses in patients with MS, and whether there is evidence that it may promote remyelination. | Liothyronine showed an acceptable safety profile in patients with MS. These data support the conduct of trials to investigate whether the drug promotes remyelination and improvement in clinical status. |

| Genchi et al. [66], 2023 | Phase I | 12 patients (8 women and 4 men) aged between 18 and 55 years, with SPMS (5 patients) or PPMS (7 patients); EDSS ≥ 6.5 and disease duration: 2–20 years | To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of intracranial transplantation of human fetal neural precursor cells in patients with PMS. | It showed that neural precursor cell therapy is feasible, safe, and tolerable. |

| Louapre et al. [67], 2023 | Phase II | 30 patients (16 women and 14 men) aged between 18 and 65 with RRMS and EDSS:0–6. 14 patients underwent treatment with IL-2, and 16 patients underwent placebo treatment | To evaluate whether low-dose IL-2 could activate and expand regulatory T cells in patients with MS and be beneficial in controlling disease activity. | The effect of low-dose IL-2 on regulatory T cells in patients with MS was delayed. However, the findings of this study and the fact that regulatory T cells promote remyelination in MS models support the conduct of larger studies with higher doses and new administration regimens. |

| Nezhad et al. [68], 2024 | Randomized, controlled, longitudinal clinical trial | 24 women aged between 18 and 45 years old, with MS, EDSS ≤ 4.0 and no regular physical activity in the last 6 months | To evaluate the effects of resistance training on serum levels of BBB permeability indices (MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, S100B) and cognitive performance in women with MS. | Moderate-intensity resistance exercises can modify biomarkers of BBB pathology in MS, although the role of S100B, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and the MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio in MS remains unknown. |

| Nakamura et al. [69], 2024 | Phase II | 195 participants (112 women and 83 men) with PPMS (107 patients) or SPMS (88 patients) with at least 4 analyzable MRIs: 97 patients underwent treatment with ibudilast and 98 underwent placebo treatment | To evaluate whether treatment with ibudilast can reduce the progression of slow-growing brain lesions in patients with MS over 96 weeks. | Ibudilast reduced the activity of chronic active lesions in MS and had an effect on compartmentalized inflammation, demonstrating its neuroprotective potential. |

BBB: blood-brain barrier; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; EDSS: expanded disability status scale; IFN: interferon; MMP: matrix metalloproteinases; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: multiple sclerosis; NfL: neurofilament light chain; PMS: progressive MS; PPMS: primary PMS; RRMS: relapsing-remitting MS; SPMS: secondary PMS; TIMP: tissue inhibitors of MMP; CNS: central nervous system; IL: interleukin.

The study by Gold et al. [58] evaluated the use of raltegravir, an antiretroviral drug used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, in reducing inflammatory activity in patients with RRMS (Table 2). Inflammatory markers (IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, IL-12p70, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) as well as serum expression of CD163 remained within normal limits before and after the intervention. Raltegravir was well tolerated, with none requiring discontinuation of treatment. A total of 245 adverse events (AEs) were reported in the 31 participants, the most common being headaches, fatigue, nausea, mild gastrointestinal disturbances, and general malaise [58].

Hartung et al. [60] investigated temelimab, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against the human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)-W envelope protein in RRMS patients (Table 2). The drug was safe and well-tolerated but did not achieve the primary endpoint (reduction in cumulative T1 lesions between weeks 12 and 24). However, at week 48, patients treated with 18 mg/kg of temelimab had fewer new T1 hypointense lesions (P-value = 0.014) and reduced brain volume loss (27.1% at week 48 and 15.4% at week 96). The loss of cerebral cortex and thalamus volume was reduced by 31.3% and 71.6% at week 48, and 41.9% and 42.6% at week 96, respectively. A dose-response effect was also observed in the maintenance of thalamus volume (P-value = 0.01 at week 48; P-value = 0.04 at week 96) and a similar trend for cortical volume (P-value = 0.10; P-value = 0.06, respectively). In addition, reductions or stabilizations were also observed in the transfer rate of magnetization in the lesions compared to the placebo group. The progression of disability, measured by EDSS was similar between groups. Regarding drug safety, 26 AEs were reported in 22 participants of the main study, including respiratory tract infections, nasopharyngitis, and musculoskeletal disorders; two severe cases (breast cancer and toxic hepatitis) were reported during the extension phase [60].

Soiza et al. [59] compared the loss of brain volume in RRMS patients treated with ocrelizumab, a monoclonal antibody that eliminates CD20+ B lymphocytes and suppresses acute inflammation, with the loss of volume in healthy subjects (Table 2). Patients treated with ocrelizumab presented brain volume loss rates similar to those of healthy controls, suggesting that patients lose brain volume at a rate close to the physiological rate. Patients treated with IFN-β-1a had higher rates of brain volume loss compared to healthy controls, which confirms the lower efficacy of this drug. The greatest losses of brain volume were observed in the thalamus region, both in healthy individuals and in patients. This region is known to be sensitive to degeneration in both aging and MS [59].

The trial of Zurmati and Khan [55] aimed to determine the dose-response relationship of tolebrutinib on the formation of new active brain lesions in MS patients (Table 2). At week 12, there was a dose-dependent reduction in the new lesions highlighted by gadolinium (mean standard deviation lesions/patient: placebo, 1.03 ± 2.50; 5 mg, 1.39 ± 3.20; 15 mg, 0.77 ± 1.48; 30 mg, 0.76 ± 3.31; 60 mg, 0.13 ± 0.43; P-value = 0.03), with the maximal effect at 60 mg (85% reduction; 90% of participants did not present new gadolinium-enhanced lesions; P-value = 0.03). Regarding new or increased T2 lesions, there was also a dose-dependent reduction, with the maximum effect observed at 60 mg and corresponding to an 89% reduction in new lesions. Regarding the safety of the drug, 70 participants in 130 (54%) reported the occurrence of AE, being the most common: headache (7% of participants), upper respiratory tract infections (5%), and nasopharyngitis (4%). Severe AE was reported, a relapse of MS culminating in hospitalization in the 60 mg group. It should be noted that no AE led to discontinuation of the study and treatment [55].

The study by Sy et al. [64] aimed to determine the ability of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (6 g or 12 g daily for 4 weeks) to reduce inflammatory and neurodegenerative markers, as well as its safety and possible benefits in neurological function (Table 2). Before starting therapy with GlcNAc, baseline serum levels of this compound were evaluated. The methodology used was liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry with ion pairing. However, this methodology measures the total amount of N-acetylhexosamines (HexNAc), a group that includes GlcNAc and other similar sugars. Basal HexNAc levels were found to be higher in the group that received the 6 g GlcNAc dose. We also evaluated the baseline levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-17) that were similar between both groups. Patients with lower levels of HexNAc in the serum had higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-17, which suggests more exacerbated inflammation. After treatment, serum levels of HexNAc in 6 g patients increased by 65% and 112% in 12 g patients. When treatment ended, levels returned to normal, demonstrating that the administration of GlcNAc promotes the availability and temporary increase of HexNAc in individuals with MS. There was an increase in N-glycan branching in CD4+ T cells, of 3% in the 6 g group (P-value = 0.038) and 7% in the 12 g group (P-value = 0.0065), which was reversible after treatment ended. When analyzing patients with serum NfL levels above the median (11.07 pg/mL), i.e., patients with active neuroaxonal lesions, it was observed that in the group of patients who took 12 g of GlcNAc, the NfL biomarker presented a reduction of approximately 12.5%, and this reduction was maintained even after the end of treatment. Regarding neurological function, there was a significant improvement in the patients’ EDSS scores after 4 weeks of treatment. Thus, 10 participants showed improvement, while only 2 participants saw the score aggravated (P-value = 0.019). Eight patients in the group that took 12 g of GlcNAc reported gastrointestinal changes (slight swelling, flatulence, and/or loose stools), but treatment did not need to be discontinued. Only one patient did not complete the 4-week elimination period due to an upper respiratory tract infection and a clinical relapse, and therefore, all tests are described, excluding this patient [64].

Nezhad et al. [68] evaluated the effects of resistance training on serum control levels of BBB permeability indices [matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), MMP-2, MMP-9; tissue inhibitors of MMP (TIMP), TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and S100B] and cognitive performance in women with RRMS (Table 2). In the resistance training group, there was a significant decrease in MMP-2 (7.11 ± 1.15 ng/mL to 6.35 ± 0.68 ng/mL; P-value < 0.05) and a significant increase in TIMP-2 (6.10 ± 2.26 ng/mL to 6.99 ± 2.31 ng/mL; P-value < 0.05). The MMP-2/TIMP-2 ratio also decreased significantly (1.37 ± 0.68 to 1.02 ± 0.41; P-value < 0.05). In the control group, there was a significant increase of MMP-2 (6.24 ± 5.42 ng/mL to 17.75 ± 6.02 ng/mL; P-value < 0.001) and the ratio MMP-2/TIMP-2 (1.20 ± 0.81 ng/mL to 4.08 ± 2.57 ng/mL; P-value < 0.01). The cognitive tests were applied to three tests: the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SMDT), which evaluates the speed of processing information, the California Verbal Learning Test II to evaluate the immediate verbal memory, and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised for visuospatial memory. The SMDT test showed that the post-test score (62.33 ± 15.55 ng/mL; P-value < 0.01) of the group submitted to resistance training increased significantly compared to the pre-test (55.91 ± 18.88 ng/mL; P-value < 0.01), without significant differences between groups. The California Verbal Learning Test II scores increased significantly in both groups with MS. In the group submitted to resistance training, there was a statistically significant increase (47.25 ± 7.91 ng/mL to 61.50 ± 6.12 ng/mL; P-value < 0.001). The same was also observed in the control group (51.76 ± 10.70 ng/mL to 56.30 ± 6.93 ng/mL; P-value < 0.05). The Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised scores showed a significant increase in both groups. In the group submitted to resistance training, there was an increase from 28.50 ± 6.36 ng/mL to 31.58 ± 4.71 ng/mL; P-value < 0.05. In the control group, there was a significant increase from 30.07 ± 2.81 ng/mL to 32.38 ± 2.98 ng/mL; P-value < 0.01 [68].

The study by Newsome et al. [65] evaluated the safety and tolerability of liothyronine, synthetic T3, in patients with MS and whether there is evidence that it may promote remyelination (Table 2). Only 18 patients completed the 24-week study due to the occurrence of 2 AEs. The most common AEs included gastrointestinal discomfort, fatigue, headaches, insomnia, and palpitations. Only 2 non-drug-related severe AE, a urinary tract infection, and a lumbar stenosis due to plasmacytoma have been reported. There were no relapses or progression of disability throughout the study. Scores on the HSS, EDSS, SDMT, MS Functional Composite, Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis, and Mood 24/7 scales remained stable throughout the study. In the CSF analysis, there were changes in 46 proteins (19 increased and 27 decreased) related to immune function, such as TACI, NKp46, IgA, and IgD, and angiogenesis, such as Cadherin-5, sTIE-1, and ANGPT2. Proteins related to angiogenesis showed an increase, while those related to the immune system decreased [65].

In the Genchi et al. [66] trial, patients were divided into four cohorts, with each patient receiving a single intrathecal administration of one of the four increasing doses of intrathecally transplanted human fetal neural precursor cells (hfNPC) treatment (Table 2). Short-term (up to 24 hours) and medium-term (up to 14 days) AEs were designated as mild and possibly associated with lumbar puncture, due to the close temporal relationship, disease, and joint use of other drugs. In the follow-up period of 2 years, the AE observed were grade 1 or 2, except for a relapse of MS, classified as a severe AE. There were also two expected grade 1 AEs, characterized by an increase in creatinine, probably related to hfNPC and concomitant treatment with tacrolimus. The parameters for motor evoked potential and sensory evoked potentials were already impaired at the beginning of the study. The plasma levels of GFAP increased statistically significantly 2 years after transplantation (P-value = 0.03), which indicates astrocytic reactivity. Six patients developed new T2 brain lesions in the follow-up period, three of which presented gadolinium-enhanced lesions. Higher doses of hfNPC correlated with lower gray matter atrophy (P-value = 0.04) and brain volume loss (P-value = 0.02). The CSF analysis showed a significant increase in proteins and cells 3 months after transplantation (protein mean: 40.8 ± 10.8 mg/dL versus 47.6 ± 13.2 mg/dL; P-value = 0.01; cell mean per microliter: 2.6 ± 1.6 versus 7.9 ± 6.9; P-value = 0.01). Microchimerism analysis of a patient detected the presence of donor cells, which demonstrates the survival and integration of the transplanted cells. Significant changes were observed in several cytokines of the CSF after transplantation and highlight the increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, neurotrophic factor derived from glial cell line, FAS-ligand, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, and vascular endothelium growth factor C) and reduction of IL-8, a pro-inflammatory cytokine. In the low dose group, an enrichment of the innate immune system pathways was observed, such as neutrophil degranulation. The enrichment analysis of pre-gene sets performed showed a tendency towards negative regulation of innate immunity pathways and a positive regulation of pathways associated with nervous system development, neurogenesis, and cellular migration. Metabolomic analysis identified statistically significant changes in 8 (out of 128) and 18 (out of 100) metabolites related to aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan), which may reflect the disease phenotype and not the treatment effect [66].

Kolind et al. [61] evaluated the myelin water fraction (MWF) in patients with RRMS treated with IFN-β-1a or ocrelizumab for 2 years, followed by an open extension of treatment with ocrelizumab for 2 years (Table 2). In patients treated with ocrelizumab during the double-blind period, MWF remained stable or even improved slightly in all brain regions. In the group of patients treated with IFN-β-1a, the MWF decreased, which highlights the loss of myelin. The differences in the various brain regions of white matter were statistically significant (P-value between 0.008 and 0.05). During the open extension period, MWF of patients who switched from IFN-β-1a to ocrelizumab stabilized or increased in normal-looking white substance. The MWF in patients who continued to take ocrelizumab since the beginning of the study remained stable, which demonstrates the preservation of myelin integrity. The MWF in chronic lesions in the group of patients who changed from IFN-β-1a to ocrelizumab decreased by 2.8%. The difference between the groups during the 4 years of study was statistically significant (P-value = 0.02), highlighting the protective effect on myelin of ocrelizumab versus IFN-β-1a [61].

Abdelhak et al. [62] evaluated whether treatment with clemastin fumarate, an antihistamine with remyelinating potential, reduces NfL levels in patients with RRMS without disease progression (Table 2). There was a reduction of 9.6% in the plasma levels of NfL (mean = 6.33 pg/mL) compared to the placebo period (mean = 7.00 pg/mL) (P-value = 0.041), confirmed by the application of Z-scores. Regarding the correlation between visual function and NfL levels, it was found that higher NfL levels were associated with later P100 latencies (B = 1.33, P-value = 0.015), indicating that greater axonal damage is reflected in a greater delay of visual conduction [62].

Louapre et al. [67] studied the ability of low-doses of IL-2 to regulate the immune system in RRMS (Table 2). Although the primary outcome (increase in regulatory T cells on day 5) was not achieved, there was a significant increase on day 15 (P-value < 0.001) in the group submitted to IL-2 at low doses (median [percentile 25.75]; 1.26 [1.21–1.33]) compared to the placebo group (1.01 [0.95–1.05]). As the primary endpoint was not reached, the researchers decided to test whether regulatory T cells in MS patients were less sensitive to IL-2 by measuring pSTAT5, CD25, soluble CD25, CD56hi NK cells, CD19+ B cells, and the DMTs that patients were subjected to. The percentage of pSTAT5 cells after exposure to IL-2 was similar in both groups, which shows that there is no sensitivity defect. CD25, a regulatory T cell activation marker, showed a statistically significant increase (P-value < 0.0001) on day 5 in the group submitted to IL-2 at low doses (2.17 [1.70–3.55]) when compared with the placebo group (0.97 [0.86–1.28]). In the serum of patients treated with IL-2 at low doses, there was also an increase in soluble CD25. Thus, it is possible to conclude that the cells acquired an activated phenotype on day 5 but only expanded on day 15. On day 5, there was also a statistically significant increase in CD56hi NK cells and a statistically significant decrease in CD19+ B cells. These findings show the role of regulatory T cells in the balance of the immune system. Regarding DMT, no statistically significant changes were observed; however, the data provide evidence that oral DMT (dimethylfumarate and teriflunomide) may have inhibited or reduced the activation capacity of regulatory T cells. In contrast, the injectable DMT (IFN and glatiramer acetate) allowed a slight increase in regulatory T cells. There was a total of 24 new T1 lesions enhanced by gadolinium in the placebo group and 8 in the low-dose IL-2-treated group, which shows the anti-inflammatory potential of IL-2. In the group submitted to treatment with IL-2, 6 of 14 patients (42.9%) had no new lesions in the 6 months of treatment. In the placebo group, this number was 4 out of 16 patients (25%). Regarding safety, a severe AE (pulmonary embolism) was observed during the treatment period, and a severe AE (acute myocardial infarction) during the follow-up period, both in the placebo group. The most reported AE was treatment site redness that occurred in 14 (100%) patients in the low-dose IL-2 group and 9 (56.3%) patients in the placebo group [67].

Nakamura et al. [69] evaluated whether treatment with ibudilast, an anti-inflammatory agent, can reduce the progression of SEL over 96 weeks (Table 2). Ibudilast reduced SEL volume by 21% in patients with PPMS (P-value = 0.02) and 19% in patients with SPMS (P-value = 0.07). The SEL volume was associated with worse performance in the T25FWT, 9-hole pin test, and SMDT (P-value < 0.03). After the division of patients into quartiles according to SEL volume, it was found that patients in the highest quartile of SEL had worse performance in clinical trials and greater brain atrophy. At the beginning of the study, the mean magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) in SEL was lower (difference of 0.61 points, P-value < 0.001) than the mean MTR in non-SEL lesions. It was observed that the loss of MTR in SEL was significantly lower in the group submitted to treatment with ibudilast, and there was a reduction of 0.22% (P-value = 0.036), which shows the protective effect of ibudilast on brain tissue. It was concluded that ibudilast significantly decreased the volume of SEL (23%, P-value = 0.003) and reduced the loss of MTR in SEL (0.22%/year, P-value = 0.04) [69].

The analysis of Talbot et al. [63] aimed to detect cytokines and chemokines that were increased in the CSF, then determine whether there was a relationship between them and NfL levels, MBP, IgG, and the MRI metrics of the lesions (Table 2). Increased concentrations of the following cytokines were observed in patients with PPMS compared to healthy controls, suggesting active intrathecal inflammation: CCL3 (1.97 times higher; P-value < 0.001), CXCL8 (1.60 times higher; P-value < 0.001), CXCL10 (1.76 times higher; P-value = 0.019), IL-10 (2.47 times higher; P-value < 0.001), IL12-p40 (2.11 times higher; P-value < 0.001), IL-15 (1.31 times higher; P-value < 0.001), IL-17A (1.43 times higher; P-value = 0.015), LT-α (1.21 times higher; P-value = 0.046), TNF-α (2.01 times higher; P-value < 0.001), VEGF-A (1.30 times higher; P-value < 0.001). When comparing cytokines in patients with RRMS versus patients with PPMS, increased levels were found in the following cytokines: IL-12p40 (2.52 times higher; P-value < 0.001), LT-α (1.24 times higher; P-value = 0.042), TNF-α (1.27 times higher; P-value = 0.032), CCL22 (1.60 times higher; P-value < 0.001), IFN-γ (1.81 times higher; P-value = 0.002) and IL-27 (1.35 times higher; P-value = 0.048), which indicates that the inflammatory picture is more intense in initial stages of the disease than in more advanced phases. However, patients with RRMS had lower levels of IL-7 when compared to healthy subjects (0.73 times lower; P-value = 0.017). When comparing cytokines with increased concentrations in patients with PPMS to evaluate the relationship between them and NfL, MBP, and IgG levels, it was found that most biomarkers did not show correlation. However, IL-15 correlated significantly with NfL and MBP (P < 0.05). IL-10, IL-12p40, TNF-α, and LT-α correlated with the IgG index. This refers to the idea that although inflammation exists, it is not strongly associated with damage and demyelination in PPMS [63].

To facilitate comparison between the therapeutic strategies discussed, Table 3 summarizes the main disease-modifying and experimental therapies according to their site of action, molecular target, BBB penetration, and primary mechanism of action.

Therapeutic strategies in multiple sclerosis.

| Therapy | Place of action | Molecular target | Penetration in the BBB | Primary therapeutic mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raltegravir | CNS and periphery | Integrase of HERV-W | Yes | Inhibition of HERV-W integration reduces the expression of neurotoxic proteins associated with microglial activation and neurodegeneration. |

| Temelimab | CNS | HERV-W envelope protein | Not significant | Neutralization of the HERV-W envelope protein reduces microglial activation, inflammation, and toxicity on OL. |

| Ocrelizumab | Periphery | CD20 of B lymphocytes | No | Elimination of CD20+ B cells, reducing antigen presentation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. |

| Tolebrutinib | CNS and periphery | BTK | Yes | Inhibition of BCR and TLR signaling in B cells and microglia modulates compartmentalized inflammation in the CNS and chronic microglial activity. |

| N-Acetylglucosamine | CNS and periphery | Hexosamine pathway | Yes | Increased branching of N-glycans, promotes immune signaling regulation, reduces TH1/TH17 responses, microglial modulation, and supports remyelination. |

| Liothyronine | CNS | Thyroid hormone nuclear receptors | Yes | Stimulation of OPC differentiation and promotion of remyelination. |

| Clemastine | CNS | Muscarinic receptors | Yes | Removal of barriers to oligodendroglial differentiation. |

| Low-dose IL-2 | Periphery | CD25 regulatory T cells | No | Expansion of regulatory T lymphocytes, restoring immune tolerance. |

| Ibudilast | CNS and periphery | Phosphodiesterases | Yes | Modulation of the immune system with reduced microglial activation, chronic inflammation, and progression of brain atrophy. |

BBB: blood-brain barrier; BTK: Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CNS: central nervous system; HERV-W: human endogenous retrovirus-W; OL: oligodendrocyte; OPC: OL precursor cell; IL: interleukin; TLR: Toll-like receptor.

The clinical trials included in this review and highlighted in Table 2 analyzed the main pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies with the potential to limit neurodegeneration and promote remyelination in MS.

However, the results demonstrated both advances and limitations that persist and complicate the application of these therapeutic strategies in clinical practice due to fundamental differences between experimental settings and the biology of human MS. Animal models mimic acute demyelination in young, repair-tolerant tissues, whereas human lesions are chronic, structurally stabilized, and characterized by persistent inflammation and extracellular matrix alterations. In addition, OPCs in humans are aged and metabolically compromised, reducing their ability to respond to pro-remyelinating stimuli. These cellular, structural, and pharmacological barriers, together with limitations in CNS penetration and incomplete binding of molecular targets, explain why interventions that are effective in animal models have modest or even absent effects in human clinical trials [70–72].

Several studies continue to recognize the reduction of inflammation as a primary strategy in the fight against MS. Agents such as raltegravir, temelimab, tolebrutinib, IL-2, and ibudilast demonstrated variable efficacy, emphasizing that suppressing peripheral inflammation alone is insufficient to halt disease progression [55, 58, 60, 67, 69]. Clinical evidence shows that remyelination fails even in patients undergoing systemic inflammatory activity control, reflecting the persistence of compartmentalized inflammation in the CNS. In addition, OPCs present in chronic lesions remain functionally compromised by aging, metabolic changes, and inhibitory signals, which are not reversed by modulation of the peripheral immune system. Thus, the absence of peripheral inflammation prevents new damage from occurring but does not reprogram the lesion microenvironment to promote effective remyelination, highlighting the need for new therapeutic approaches that act directly on the CNS [34, 73].

However, trials with antiretroviral drugs alone, such as raltegravir, did not show significant clinical results, which highlights the need for studies with combination therapies or more targeted strategies [58].

In the doses tested, temelimab did not significantly reduce acute inflammation in MS, but showed promising radiological signs of possible antineurodegenerative effects. The positive effects were observed at the dose of 18 mg/kg, and, therefore, leaving uncertainty about whether higher doses might yield stronger results [60].

Although BTK inhibitors share a common molecular target, their neuropharmacological properties differentiate their potential clinical impact on PMS. BTK is functionally relevant in the CNS, particularly in microglia, where it regulates signaling pathways associated with Toll-like and Fcγ receptors, directly influencing chronic inflammatory activation, pathological phagocytosis, and aberrant synaptic clearance. Thus, the ability to cross the BBB emerges as a key factor among the various BTK inhibitors. Tolebrutinib is capable of directly modulating BTK-dependent microglial signaling, decreasing compartmentalized inflammation, excessive synaptic loss, and inhibiting OL differentiation. On the other hand, agents with limited CNS penetration, such as evobrutinib and fenebrutinib, exert peripheral immunomodulatory effects, effective in reducing B-cell-dependent inflammatory activity, but potentially insufficient to interfere with the neurodegenerative mechanisms that underlie clinical progression. Thus, these pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences suggest that BTK inhibition in the CNS, and not just in the periphery, may be crucial for achieving disease progression-modifying effects, reinforcing the need for the development of brain-penetrant BTK inhibitors for PMS [74].

Therapies that focus on B cells, namely ocrelizumab, have shown high potential in reducing inflammation and are also associated with maintaining myelin integrity when used early, as demonstrated in the studies by Soiza et al. [59] and Kolind et al. [61]. However, the results in the progressive forms are minimal, which can be linked to a low CNS penetration capacity, resulting in a compartmentalized immune response that promotes constant inflammation and neurodegeneration [59].

Therapies acting in the modulation of microglial activation, such as ibudilast, in the promotion of remyelination, such as clemastine and liothyronine, or through the administration of regulatory immune factors, such as IL-2 at low doses, show the growing need to develop therapies that target more complex processes of pathology. Low doses of IL-2 selectively expand and activate regulatory T cells due to the high expression of the high-affinity receptor for IL-2. These activated regulatory T cells with immunoregulatory effects indirectly modulate inflammation in the CNS, promoting the alteration of microglia to a stage more favorable to repair. By reducing chronic inflammatory signals that block OPC maturation, regulatory T cells create a microenvironment favorable to OPC differentiation and remyelination [67].

Liothyronine promoted CNS neuroregeneration [65], while clemastin reduced NfL, demonstrating potential as a neuroaxonal stabilizer [62].

The modest effects observed with the use of clemastine and other muscarinic M1 receptor antagonists reflect the limitations of therapeutic strategies that target a single mechanism of remyelination. Clemastine, by removing an intrinsic inhibitory signal, promotes OPC differentiation but does not significantly alter the MS lesion microenvironment. The results of the ReBUILD trial show that this partial disinhibition is sufficient to allow for modest functional improvements, namely a reduction in the latency of visual evoked potentials and a decrease in NfL levels, suggesting axonal stabilization but not robust remyelination. Based on these results, it can be concluded that, although modulation of OPC differentiation is biologically relevant, the magnitude of its clinical impact is limited when not accompanied by interventions that simultaneously modify the inflammatory and structural aspects of the lesions, especially in the chronic stages of the disease [62].

The increase in N-glycan branching appears to be a central regulatory mechanism of neuroinflammation and myelin stability. The biosynthesis of branched N-glycans promotes the formation of multivalent galectin-dependent networks on the cell surface, which regulate the mobility, clustering, and endocytosis of multiple receptors in a coordinated manner. This allows for improved proinflammatory signaling of T and B lymphocytes, leading to suppression of TH1 and TH17 responses. In the CNS, the interaction between branched N-glycans and galectins negatively regulates microglial activation, reducing chronic active inflammation. This axis exerts direct effects on OPCs, favoring their differentiation and the structural maintenance of the myelin sheath through the stabilization of receptors involved in cell survival and myelination [64].

About non-pharmacological interventions, resistance training was shown to be useful in modulating the integrity of the BBB, improving verbal memory, and modulating inflammatory biomarkers. When implemented early, personalized and integrated with pharmacological therapies seems to be a promising strategy to improve the quality of life of MS patients [68].

The use of hfNPC is an innovative strategy capable of altering the neural microenvironment by promoting neuroprotection. Although the results demonstrate an acceptable safety and tolerability profile, studies with a larger number of participants and longer follow-up periods are still needed to confirm clinical efficacy [66].