Affiliation:

1Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University Hospital Center Quebec–Laval University, Quebec City, QC G1V 4G2, Canada

2Research Centre of University Hospital Center Quebec–Laval University, Quebec City, QC G1V 4G2, Canada

Email: guillermo.costaguta.med@ssss.gouv.qc.ca

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0468-5321

Affiliation:

3Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University Hospital Center Sainte-Justine, Montreal, QC H3T 1C5, Canada

4Department of Pediatrics, Université de Montreal, Montreal, QC H3T 1J4, Canada

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0534-5142

Explor Dig Dis. 2025;4:1005104 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2025.1005104

Received: July 17, 2025 Accepted: November 02, 2025 Published: December 07, 2025

Academic Editor: Jean Francois D. Cadranel, GHPSO, France

The article belongs to the special issue Cirrhosis and Its Complications

Pediatric cirrhosis differs significantly from adult liver disease in terms of etiology, progression, and management. The unique physiological, nutritional, and developmental needs of children require specialized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. This review underscores the distinct challenges in diagnosing and managing pediatric cirrhosis, focusing on its complications, management, and outcomes. Unlike adults, where cirrhosis often results from viral hepatitis or alcohol use, pediatric cases are predominantly cholestatic, with biliary atresia being the most common cause. Complications mainly involve portal hypertension and impaired liver function, leading to malnutrition and neurodevelopmental delay. Nutritional management is complex and requires increased caloric and protein intake, supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins, and the use of medium-chain triglycerides. Although hepatocellular carcinoma is rare in children, it remains a severe complication with a higher incidence in certain genetic and metabolic disorders. Surveillance is challenging due to diagnostic limitations and the lack of standardized pediatric screening protocols. Treatment is further complicated by constraints related to size and developmental stage, particularly in the management of portal hypertension. Pediatric cirrhosis requires an individualized multidisciplinary approach to address the interplay between growth, nutrition, and liver function. Early diagnosis, nutritional optimization, malignancy surveillance, and timely referral for liver transplantation are crucial. Ongoing research on pediatric-specific therapies and outcomes is essential for improving prognosis and quality of life.

Cirrhosis in pediatric patients poses unique challenges distinct from those in adults. The specific causes, nutritional requirements, developmental considerations, and therapeutic constraints necessitate customized approaches in children. Over the last 30 years, the global prevalence of cirrhosis has risen significantly, with approximately 112 million cases of compensated cirrhosis and 10 million cases of decompensated cirrhosis [1, 2]. While the causes vary by region, the primary factors in adults are hepatocellular, mainly hepatitis B or C, and alcohol-related liver disease [3]. In contrast, pediatric cirrhosis is primarily caused by chronic cholestatic conditions, with biliary atresia being the most common, followed by Alagille syndrome, cystic fibrosis (CF), and familial intrahepatic cholestasis [4, 5]. This distinction is clinically significant, as complications in children can develop over months to years, often despite maintained liver function, and are mainly associated with portal hypertension [6]. Age-specific factors are critical, as many children develop cirrhosis during key growth periods. Children with cirrhosis often experience intestinal malabsorption of essential fatty acids, fat-soluble vitamins, and micronutrients, leading to permanent growth delays, even when their underlying condition improves. Chronically ill children have increased caloric and protein needs, which are often unmet through a normal diet alone [7, 8]. Neurodevelopment is affected by nutritional deficiencies and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) during the early developmental stages [9]. Therapeutic interventions are limited by the child's size and weight, particularly in the management of portal hypertension. Devices for variceal ligation and surgical shunts require further adaptation [10]. This article provides an overview of the unique considerations in the diagnosis and management of pediatric cirrhosis and its complications.

Cirrhosis etiologies in children.

| Category | Etiologies | Age at presentation | Hallmarks | Genetic tests | Red flags* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholestatic liver diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Hepatocellular diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Metabolic and storage diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*: In all cases, decompensated cirrhosis should prompt early evaluation for a possible liver transplantation. **: Liver transplantation for Niemann-Pick type C is still not widely adopted, and there is no formal indication to date. BSEP: bile salt export pump; MDR3: multidrug resistance protein 3; CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; HBsAg: surface antigen of Hepatitis B; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; Cu2+: copper; NA: not applicable.

Biliary atresia is a progressive necroinflammatory and obliterative condition that affects a normally developed biliary tree. It occurs in 1 in 15,000 newborns and is the leading cause of liver transplantation in pediatric patients (Table 1). Despite ongoing research, the exact pathophysiology remains poorly understood, particularly the mechanisms driving rapid fibrosis progression and early cirrhosis onset within the first few months of life [11]. Besides liver transplantation, the only palliative treatment is a hepato-portoenterostomy, as described by Morio Kasai, which is a surgical procedure connecting the porta hepatis to the digestive tract. When this procedure is successful, bile flow is reestablished; however, patients often suffer recurrent episodes of cholangitis during the early postoperative years, leading to inflammation of the small portal veins and potentially resulting in thrombophlebitis. Consequently, severe portal hypertension often develops even when hepatic function is relatively preserved. Management relies on early diagnosis and timely surgery, with the Kasai procedure ideally performed before 60 days of age. Beyond this window, transplant-free survival rates decline significantly [12]. Among those who undergo surgery within the recommended timeframe, only 75% achieve jaundice resolution and delayed transplantation. Most children with biliary atresia (70%) require liver transplantation before the age of 20 years, as advanced fibrosis is common, even in timely operated cases. When cholestasis does not improve post-Kasai (direct bilirubin > 34 µmol/L at three months postoperatively), the disease rapidly progresses to decompensated cirrhosis or liver failure. These patients typically require liver transplantation within their first year of life [13].

First identified in 1969, Alagille syndrome arises from autosomal dominant mutations in the JAG1 or NOTCH2 genes, which encode signaling proteins crucial for arterial vessel development and cell survival. Although it is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 30,000 to 50,000 live births [14, 15], the actual incidence might be higher due to variable penetrance, leading to patients with mild symptoms and improved access to genetic testing. The syndrome is characterized by intrahepatic cholestasis resulting from bile duct paucity and is associated with extrahepatic anomalies, including cardiovascular malformations (typically peripheral pulmonary stenosis), ophthalmologic findings (posterior embryotoxon), skeletal anomalies (butterfly vertebrae), distinctive facial features (broad forehead, hypertelorism, pointed chin, bulbous nose), and renal abnormalities [16]. Clinical diagnosis requires bile duct paucity and at least three of the five major clinical features. Genetic testing has facilitated earlier recognition, often prompted by extrahepatic manifestations [17]. Cases without hepatic involvement suggest that prevalence estimates may be skewed due to a selection bias towards patients with liver disease [18, 19]. A notable feature is marked hypercholesterolemia, which can lead to xanthomatosis. Although xanthomas can be pruritic, they are usually asymptomatic and do not affect disease progression [20]. As a multisystem disorder, Alagille syndrome requires multidisciplinary management. Affected children often exhibit growth failure and neurodevelopmental delays, although the pathophysiology is not fully understood [21]. These complications are likely multifactorial, with cholestasis contributing to nutrient malabsorption. Cholestatic pruritus can be severe and resistant to treatment, often impairing quality of life and necessitating liver transplantation [22]. Pruritus causes sleep disturbances, affecting school performance, mood, and possibly growth hormone secretion, as its release peaks during sleep, which may contribute to growth failure [21, 23]. Approximately 30% of children with Alagille syndrome require liver transplantation before the age of 18 years due to cirrhosis complications or intractable pruritus.

CF is the most common inherited genetic disorder among Caucasian populations, resulting from mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene on chromosome 7. This gene encodes a chloride channel crucial for the transport of electrolytes and fluids across epithelial surfaces. When CFTR is dysfunctional, glandular secretions thicken, leading to clinical symptoms in the lungs, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and liver [24]. Traditionally, CF-associated liver disease (CFLD) was believed to stem from chronic cholestasis due to inspissated bile obstructing the biliary tree [25]. However, recent evidence challenges this perspective. Many patients with CFLD do not develop classical cirrhosis, and those with portal hypertension often exhibit minimal fibrosis on biopsy and lack typical biochemical markers of cholestasis [26]. Research indicates that CFTR influences the innate immune response, and its dysfunction fosters a proinflammatory hepatic environment. Our groupʼs analysis of liver explants from transplanted CF patients consistently revealed portal vein vasculopathy, possibly resulting from chronic inflammation due to bacterial or toxin exposure via portal circulation, as proposed by Fiorotto and Strazzabosco [27]. This finding aligns with earlier studies that identified “focal biliary cirrhosisˮ once considered the hallmark of CFLD, in only 5–10% of cases, a pattern not seen in other liver diseases [28]. Most CFLD patients, especially those reaching adulthood due to improved pulmonary care, experience severe portal hypertension without cirrhosis. This non-cirrhotic portal hypertension likely arises from chronic portal venopathy and progressive vascular remodeling [29]. Our recently published histological review of liver explants from CF patients confirmed the presence of diffuse thickening of the portal vein walls throughout the liver parenchyma [29].

The management of CFLD primarily targets the treatment of cholestasis and control of portal hypertension. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is used to treat cholestasis, although its impact on altering the disease course is limited, despite improvements in liver biochemistry [30]. CFTR modulators, originally developed for pulmonary conditions, have improved survival rates and may also offer benefits for liver disease, as suggested in a recent systematic review. The use of CFTR modulators resulted in varying effects on transaminases and γGT levels, with a more pronounced decrease observed when using lumacaftor/ivacaftor compared to elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor. In contrast, direct bilirubin trends were more consistent across studies, showing a decrease with the former combination but an increase with the latter. While current data are promising, they remain inconclusive [31]. Given that liver function is generally preserved while portal hypertension is prominent, management strategies focus on preventing and treating variceal bleeding. Although endoscopic therapy is effective, it often necessitates multiple anesthesia sessions, posing risks to patients with pulmonary compromise [32]. In selected cases, surgical shunts or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) may be used to decompress the portal system. However, these interventions require careful consideration because of their effects on pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with compromised lung function [33–35].

PFIC is a group of autosomal recessive disorders marked by hepatocellular cholestasis resulting from mutations in genes that encode proteins crucial for bile production and excretion [36, 37]. A distinctive feature of most PFIC types is low or normal γGT levels, indicating intrahepatic bile retention rather than canalicular stasis, except for MDR3 deficiency (formerly, PFIC3). FIC-1 deficiency, also known as Byler's disease, arises from mutations in ATP8B1, which encodes the FIC-1 protein responsible for the translocation of amino-phospholipids, a process vital for maintaining the integrity of the bile canalicular membrane. Patients typically present with neonatal cholestasis, diarrhea, failure to thrive, and sensorineural hearing loss, reflecting the expression of FIC-1 in extrahepatic tissues. Management requires a multidisciplinary approach, and while liver transplantation can alleviate hepatic symptoms, it does not address extrahepatic manifestations.

Bile salt export pump (BSEP) deficiency, previously known as PFIC2, arises from mutations in the ABCB11 gene, which impair the BSEP and result in bile salt accumulation within the liver. Disease severity is influenced by the residual activity of BSEP, which is determined by specific mutations [38, 39]. Patients typically present in infancy with severe cholestasis, which can progress to cirrhosis and its associated complications. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can develop before adulthood. Unlike FIC-1, liver transplantation offers a cure for BSEP deficiency; however, the disease can relapse due to the development of BSEP antibodies in those who lack the protein in their native liver. Some ABCB11 mutations express phenotypically as benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC), characterized by intermittent cholestatic episodes, with pruritus as the predominant symptom [40].

MDR3 deficiency, previously known as PFIC3, is caused by mutations in the ABCB4 gene and characterized by elevated γGT levels. The MDR3 protein facilitates the secretion of phosphatidylcholine into bile, which helps solubilize bile acids and protects cholangiocytes. Clinical symptoms typically manifest during late childhood or adolescence. Liver transplantation is considered in cases of chronic liver failure or decompensated cirrhosis [41]. Advanced genetic testing has uncovered new PFIC-like disorders, including mutations in TJP2 (essential for functional cell-cell junctions), NR1H4 [coding for farnesoid X receptor (FXR), which regulates BSEP expression], and MYO5B (involved in BSEP protein localization). These mutations often lead to phenotypes resembling mild-to-moderate BSEP deficiency. Additional genes, such as USP53, KIF12, and LSR, have been suggested as potential causes of PFIC, although their natural histories are still being studied [42]. The management of PFIC is similar to that of other pediatric cirrhosis causes, with one notable difference: cholestatic pruritus, which severely affects up to 80% of patients [43]. Treating pruritus remains challenging because of its poorly understood pathophysiology.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis collectively affect 2–17 per 100,000 children. Similar to adults, these conditions exhibit female predominance, although the sex difference may be less pronounced in pediatric cases [44]. AIH is immunologically classified into type 1 (positive for anti-nuclear antibodies and/or smooth muscle antibodies) and type 2 (positive for anti-LKM antibodies and/or anti-cytosol antibodies). This classification is significant because type 2 AIH often presents at a younger age and follows a more aggressive course, with a higher risk of progression to liver failure. Approximately 40% of type 1 and 80% of type 2 cases are diagnosed before the age of 18 years [45]. The clinical presentation varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic elevation of liver enzymes to acute liver failure, cholestatic hepatitis, or chronic liver disease with cirrhotic complications already present at diagnosis [44]. Studies have shown that 40–90% of patients with pediatric autoimmune liver disease eventually develop cirrhosis, particularly those without remission [46]. First-line treatment typically involves high-dose corticosteroids combined with steroid-sparing immunomodulators (e.g., thiopurines or mycophenolate mofetil) [47]. This approach achieves remission in 80–90% of cases; however, up to 20% of children require alternative, non-standardized therapy [48]. Given the side effects of high doses of corticosteroids, personalized initial treatment to induce complete remission should be seriously considered in adolescent girls, those with diabetes, glomerulonephritis, severe stretch marks or acne, other autoimmune diseases, and immunodeficiencies. Effective treatment is crucial not only to control disease progression but also because fibrosis regression is possible. For patients who fail to achieve remission or progress despite treatment, liver transplantation remains the only curative option [49].

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in children progresses through distinct phases characterized by interactions between the immune system and the virus. A pivotal milestone in this progression is seroconversion from hepatitis B e-antigen to anti-HBe antibody, which signifies a shift to low or very low viral replication and, consequently, a less active disease state. The duration of the replicative phase is linked to the risk of severe outcomes, such as cirrhosis and HCC [50]. Although the estimated incidence of cirrhosis in HBV-infected children is less than 4%, this figure rises to approximately 25% in those co-infected with the hepatitis delta virus [51]. Some pediatric cases even show regression of cirrhosis during long-term follow-up. Children infected vertically tend to remain in the immunotolerant phase longer and develop complications later than those infected horizontally because of a less robust immune response at the time of infection. Currently, the most effective strategy for combating HBV is vaccination. The widespread implementation of pediatric vaccination programs has yielded significant public health benefits in both low- and high-income countries [52, 53]. When administered within 24 h of birth, in conjunction with HBV immunoglobulin, the vaccine is 85–95% effective in preventing vertical transmission and its associated long-term complications. The use of nucleoside analogs in mothers with high viral replication during the third trimester of pregnancy approaches 100% effectiveness in preventing vertical transmission when combined with vaccination and HBV immunoglobulins [54]. Nonetheless, in cases where prevention fails, recent antiviral advancements, including an antisense oligonucleotide targeting HBV RNA (bepirovirsen), have shown promise in clearing HBV DNA in chronic infections [55], raising the possibility of HBV eradication in the next decade [56].

In contrast, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection generally presents a milder course in children than in adults. Pediatric cases, especially those acquired vertically, are often asymptomatic, with normal or near-normal ALT levels and minimal histological changes on biopsies. Cirrhosis occurs in only 1–2% of children with chronic HCV [57], and HCV-related liver disease accounts for less than 1% of pediatric liver transplants in the SPLIT registry, in stark contrast to adult populations. This difference reflects the slow progression and limited risk factors in children [58]. Currently available antiviral treatments can clear almost 100% of the virus, regardless of genotype, and are available from the age of 3 years, indicating that HCV eradication may be possible in the future.

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder resulting from mutations in the ATP7B gene, which encodes a copper-transporting ATPase that is crucial for hepatic copper excretion. Impairment of this function leads to toxic copper buildup in the liver, brain, and other organs [59]. Pediatric presentations vary widely, from asymptomatic hepatomegaly to acute liver failure. Early diagnosis is vital, and Wilson disease should be considered in all children with unexplained liver dysfunction [60]. As copper accumulates, steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis can develop, sometimes as early as the age of 3 years. Diagnosis relies on a combination of findings: low serum ceruloplasmin, elevated 24-h urinary copper, and high hepatic copper content (≥ 250 μg/g dry weight). While genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis, it may not be available in urgent situations [61]. Treatment involves chelating agents, such as penicillamine or trientine, and zinc salts to inhibit copper absorption. Liver transplantation may be necessary in cases of acute liver failure or decompensated cirrhosis. However, even in advanced disease, chelation therapy is recommended, as some patients have shown marked improvement without transplantation [60].

A1AT deficiency is the most prevalent genetic cause of neonatal cholestasis in Western countries, occurring in approximately 1 in 1,500–2,000 live births. Liver disease is linked to the PiZZ variant, a misfolded protein that accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes, leading to inflammation and hepatocellular injury, thereby illustrating the toxic gain-of-function mechanism [62]. Clinical outcomes vary; 17% of PiZZ infants exhibit neonatal cholestasis, 20% develop cirrhosis, and 80% remain free of liver disease by age 18, according to population-based studies. However, data from specialty centers indicate cirrhosis rates as high as 40%, particularly among those with persistent liver abnormalities, although these figures may be skewed due to the selected nature of patients in specialized centers [63]. Given its wide phenotypic range, A1AT deficiency should be considered in children with unexplained cirrhosis and a history of neonatal cholestasis. While enzyme replacement is effective for pulmonary manifestations, it is ineffective for hepatic disease resulting from intracellular accumulation. Histological hallmarks include PAS-positive, diastase-resistant globules in hepatocytes. The only curative treatment for decompensated cirrhosis is liver transplantation. Persistent jaundice and coagulopathy are poor prognostic factors [64].

Children with GSD III and IX may experience liver fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis, typically emerging during adolescence or early adulthood. In GSD type III, muscle involvement, including cardiomyopathy, is common and indicated by elevated creatine phosphokinase levels. These patients are generally not considered candidates for transplantation unless liver disease progresses significantly. Treatment primarily focuses on maintaining normoglycemia through frequent feeding with complex carbohydrates. Liver transplantation may be considered if the disease is confined to the liver. Similar principles apply to GSD type IX, with diagnosis confirmed through biochemical testing and genetic analysis [65, 66]. GSD type I warrants a brief mention, as cirrhosis rarely occurs as an isolated complication of the disease. However, patients often experience severe fatty infiltration of the liver, which can lead to scarring and eventually cirrhosis. Under these conditions, along with the development of adenomatosis, malignant transformation is a common scenario that must be closely monitored by the treating physician [67].

GSD type IV arises from a deficiency in the glycogen branching enzyme, leading to the accumulation of amylopectin-like polysaccharides in the liver, skeletal muscle, and heart. In its hepatic form, infants develop progressive liver disease, often culminating in cirrhosis within the first few years of life. Currently, liver transplantation is the only effective treatment. Although early post-transplant outcomes appear promising, there have been reports of fatal cardiac complications, and no reliable markers exist to predict which patients are at risk of such outcomes [67].

This lysosomal storage disorder arises from defective intracellular cholesterol trafficking, although its exact pathophysiology is unclear. It is the second most common genetic cause of neonatal cholestasis after A1AT deficiency, accounting for approximately 8% of neonatal cholestasis cases and 25% of those with a neonatal hepatitis-like syndrome [68]. Infants may present with ascites, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly. Notably, splenomegaly often persists, serving as a diagnostic clue, particularly when accompanied by neurological symptoms. Liver biopsy may reveal hepatocellular cholestasis, ductal proliferation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ductopenia, the latter being associated with a poor prognosis. Currently, there is no effective therapy for hepatic disease, but emerging neurological treatments could make liver transplantation a feasible option for selected patients [69].

IFALD is a significant complication in pediatric patients on long-term parenteral nutrition, especially neonates and infants. It includes liver damage ranging from cholestasis and hepatic steatosis to fibrosis and cirrhosis. This condition frequently affects children with short bowel syndrome or intestinal failure and remains a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality in this population [70]. The pathophysiology of IFALD is complex and multifactorial. Prolonged exposure to PN, particularly lipid emulsions high in omega-6 fatty acids derived from soybean oil, plays a central role. These formulations induce proinflammatory effects and impair bile flow. The absence of enteral feeding reduces bile secretion and disrupts gut-liver signaling, leading to cholestasis. Infections, particularly catheter-related bloodstream infections, can exacerbate liver injury through systemic inflammation and endotoxemia. Preterm infants, who make up a large proportion of patients with intestinal failure, have immature hepatobiliary systems, making them more vulnerable to liver damage [71]. Clinically, IFALD may initially present with mild elevations in liver enzyme levels or direct hyperbilirubinemia. As liver damage progresses, children may develop jaundice, coagulopathy, hepatomegaly, and portal hypertension. Growth failure is common and reflects nutritional deficits and liver dysfunction. Diagnosis relies on persistent conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, abnormal liver function tests, and imaging findings. In advanced cases, liver biopsy may be necessary to assess fibrosis [72]. Prevention and early intervention are crucial for managing IFALD. Strategies include cycling parenteral nutrition, rapidly advancing enteral feeding, and using fish oil-based lipid emulsions, which have hepatoprotective properties. Preventing infections through catheter care and monitoring liver dysfunction are essential. Surgical interventions increasing intestinal length may reduce PN dependence. Liver or combined liver-intestinal transplantation may be necessary for children with end-stage liver disease who are unsuitable for intestinal rehabilitation [73].

FALD is a progressive hepatic complication seen in children and adolescents with single-ventricle congenital heart disease who have undergone the Fontan procedure. This surgical intervention reroutes systemic venous blood directly to the pulmonary arteries, bypassing the heart. Although life-saving, Fontan circulation results in elevated central venous pressure and reduced cardiac output, imposing hemodynamic stress on the liver through congestion and hypoxia. Over time, this leads to sinusoidal dilation, perisinusoidal fibrosis, and eventually, bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. Hepatic arterialization may temporarily preserve liver function but also contribute to architectural distortion. Unlike other causes of pediatric cirrhosis, FALD is driven by vascular congestion and hypoxia, rather than inflammation [74]. Initially, children with FALD are often asymptomatic, and liver dysfunction may remain undetected for several years. As fibrosis progresses, symptoms such as hepatomegaly, ascites, and splenomegaly may develop. Portal hypertension can develop even when liver synthetic function is preserved, which complicates its management. Laboratory tests may remain normal until the disease is advanced, making imaging and histological evaluations crucial. Elastography, Doppler ultrasound, and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) assess liver stiffness and structural changes, although liver biopsy remains the standard for fibrosis staging [75]. However, the variable degree of congestion complicates the interpretation of the results. Management focuses on optimizing Fontan physiology, maintaining low venous pressure, and ensuring adequate cardiac output. Diuretics help control volume status, and addressing arrhythmias or Fontan circuit obstruction is critical. There are no disease-specific therapies for FALD, and progression can occur despite stable cardiac function. Surveillance is essential, particularly for HCC, which has been reported in pediatric and young adult Fontan patients, even without overt cirrhosis [76]. Liver transplantation with Fontan physiology presents challenges, and in cases of end-stage liver and cardiac disease, combined heart–liver transplantation may be necessary. As the number of long-term Fontan survivors increases, FALD is becoming a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality, necessitating coordinated multidisciplinary care and structured follow-up [77].

MASLD, formerly referred to as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is the most prevalent chronic liver disease in children. Present estimates suggest that MASLD affects 3–10% of all children, with notable geographic variations, especially in high-income countries. Among children who are overweight or obese, the prevalence of MASLD exceeds 30% [78]. The recent change in terminology highlights the etiology of the disease rather than the exclusion of alcohol. In pediatric populations, MASLD is associated with metabolic syndrome and its components, including obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, diabetes, and hypertension [79]. The severity of the disease ranges from mild forms, characterized by simple liver steatosis and slight elevation of liver enzymes (often less than twice the upper limit of normal), to advanced phenotypes with lobular inflammation, necrosis, and varying degrees of fibrosis, which frequently progress to cirrhosis.

The pathophysiology of MASLD involves intricate interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental influences, and metabolic dysfunction [80]. A central factor appears to be insulin resistance, which promotes unregulated lipolysis in adipose tissue, leading to an increase in circulating free fatty acids that are absorbed by the liver. This process contributes to hepatic steatosis through enhanced de novo lipogenesis and impaired β-oxidation. Lipid accumulation within hepatocytes makes the liver more susceptible to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, which drive inflammation and hepatocellular injury [81]. Additionally, gut microbiota dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability may exacerbate hepatic inflammation via endotoxin translocation [82]. Genetic polymorphisms in PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and GCKR influence disease susceptibility and progression in the pediatric population [83]. These mechanisms contribute to the progression from simple steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and fibrosis, underscoring the systemic nature of the disease and its association with metabolic dysfunction.

The diagnosis of MASLD requires the integration of clinical, biochemical, and imaging findings. Elevated aminotransferase levels, in the absence of alternative liver disease causes, often prompt further investigation. Although ultrasound is commonly used as an initial imaging tool because of its accessibility, it lacks sensitivity for detecting mild steatosis and offers limited information on fibrosis. Non-invasive techniques, such as transient elastography and magnetic resonance imaging-based proton density fat fraction, are increasingly employed for diagnosis and monitoring. While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing MASH and assessing fibrosis, its invasive nature restricts its routine use. Management primarily focuses on lifestyle interventions, including dietary changes and physical activity, which have proven effective in reducing hepatic steatosis and improving insulin sensitivity. No pharmacologic therapy is currently approved for MASLD treatment, and although numerous agents are under investigation, none have been approved for pediatric patients [84].

Cirrhosis in children can lead to a wide array of complications, each necessitating tailored management strategies (Table 2). Conceptually, these complications can be categorized into those stemming from increased hydrostatic pressure (due to portal hypertension) and those resulting from impaired liver function. Further subclassifying hydrostatic complications into those that can be alleviated by portal pressure decompression and those that cannot be improved by decompression offers a practical approach to clinical management. Some complications may involve both mechanisms; however, this classification remains valuable in guiding treatment.

Cirrhosis complications in children.

| Category | Complication | Treatment | When to admit | Pearls and pitfalls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrostatic pressure-related complications | Treatable by portal system decompression | Ascites | Sodium restriction |

|

|

| Spironolactone 3–6 mg/kg | |||||

| Furosemide 1 mg/kg | |||||

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 3rd generation cephalosporins |

|

| ||

| Gastroesophageal varices | Endoscopic band ligation |

|

| ||

| Octreotide 1–5 µg/kg/h | |||||

| Proton pump inhibitors BID | |||||

| 3rd generation cephalosporins | |||||

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Terlipressin + albumin |

|

| ||

| Liver transplantation | |||||

| Not treatable by portal system decompression | Hepatic encephalopathy | Lactulose 5–30 mL TID-QID |

|

| |

| Rifaximin 10–15 mg/kg/day BID | |||||

| Porto-pulmonary hypertension | Endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan) |

|

| ||

| Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (sildenafil) | |||||

| Prostacyclin analogues (epoprostenol) | |||||

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | Liver transplantation |

|

| ||

| Not pressure-related complications | Malnutrition | MCT and essential fatty acids supplementation |

|

| |

| Vitamin A: 5,000–10,000 IU/day | |||||

| Vitamin D: 2,000–5,000 IU/day | |||||

| Vitamin E: 20–100 IU/kg | |||||

| Vitamin K: 2–10 mg/day | |||||

| Zinc: 1–2 mg/kg/day | |||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Surgical resection |

|

| ||

| Immunotherapy (PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4) | |||||

| Pembrolizumab (pediatric dose to be determined) | |||||

| Liver transplantation | |||||

*: Some centers adopted the use of carvedilol as primary prophylaxis, though not much literature exists to formally adopt this practice, and its use is left to the clinician’s judgment. BID: twice daily; EVL: endoscopic variceal ligation; AKI: acute kidney injury; TID: thrice daily; QID: four times a day; NH3: ammonia; MCT: medium-chain triglycerides; BMI: body mass index; ADEK vitamins: vitamins A, D, E, K; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4.

Portal hypertension is characterized by an increased pressure gradient between the portal and hepatic veins. Clinically, it is diagnosed when the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) exceeds 5 mmHg and becomes significant when it exceeds 10 mmHg. Its effects include the formation of collateral vessels, altered vascular tone, and increased plasma volume with high cardiac output. These changes are mediated by the release of vasoactive substances and vascular endothelial growth factor [85].

Ascites, the most prevalent complication of cirrhosis, primarily arises from splanchnic vasodilation, which is largely attributed to increased production of nitric oxide. This leads to a reduction in the effective circulating blood volume, triggering the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and resulting in sodium and water retention. Hypoalbuminemia and elevated portal pressure promote transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. This vicious cycle results in progressive fluid accumulation and circulatory dysfunction. Data from adults indicate that 15% of cirrhotic patients die within one year and up to 44% within five years following the onset of ascites [86].

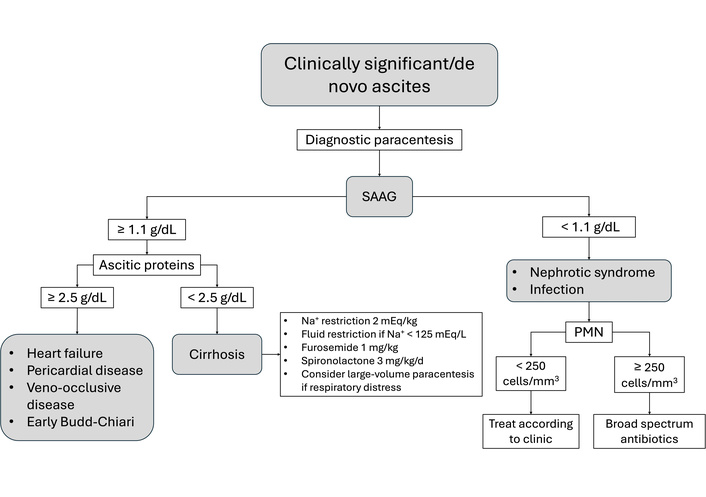

Initial management prioritizes the early diagnosis of the etiology of new-onset ascites and treatment of the underlying cause and/or liver disease, which may lead to regression of ascites (Figure 1). Following the initial clinical assessment, which includes a physical examination and evaluation of liver and renal function through biochemical parameters, an abdominal ultrasound should be performed to assess the presence and quantity of ascites. In cases of new-onset ascites or significant changes in ascitic volume during episodes of decompensation, diagnostic paracentesis is warranted to analyze ascitic fluid [87, 88]. The serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) is of diagnostic importance and plays a central role in determining the underlying cause. A SAAG ≥ 1.1 g/dL indicates portal hypertension or heart failure, whereas a total protein concentration in the ascitic fluid < 2.5 g/dL supports a hepatic etiology [89]. Although not part of the SAAG itself, additional analysis of neutrophil count, presence of bacteria, triglyceride levels, and chylomicrons in ascitic fluid can provide further insight into the etiology of ascites. Once an etiological diagnosis is made, management depends on the cause. Sodium restriction is crucial, typically aiming for 2 mEq/kg, often achieved through a no-added-salt diet [87]. Contrary to intuitive practice, fluid restriction is not routinely recommended unless there is severe hyponatremia (< 125 mEq/L) or fluid intake significantly exceeds urine output [88]. Diuretics are introduced when dietary measures are insufficient. For mild ascites, spironolactone is initiated at 3 mg/kg/day (up to 100 mg), gradually increasing to 6 mg/kg/day (maximum: 400 mg). In cases of moderate ascites, furosemide is added at 1 mg/kg, maintaining a spironolactone:furosemide ratio of 2.5:1 to optimize synergy and minimize side effects. Alternatives such as hydrochlorothiazide, triamterene, and metolazone may be used, but carry a higher risk of hyponatremia and cost [90]. In instances of tense ascites, large-volume paracentesis (up to 200 mL/kg) is performed to relieve discomfort. To prevent post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction, 25% albumin is administered at 1 g/kg, divided between an initial 2-h and a prolonged 6–8-h infusion [91]. Although adult studies suggest that weekly albumin infusions may improve outcomes in decompensated cirrhosis, current data remain inconclusive due to study heterogeneity [92].

Simplified clinical pathway for the management of ascites. SAAG: serum-ascites albumin gradient; PMN: polymorphonuclear cells.

SBP is a life-threatening infection of ascitic fluid in cirrhotic patients, occurring without an identifiable intra-abdominal source [93], regardless of the amount of accumulated ascites. The pathophysiology involves bacterial translocation from the gut due to immune dysregulation in patients with cirrhosis [94]. In children, the hematogenic pathway explains the high frequency of gram-positive peritonitis. Clinical signs such as fever, chills, or abdominal tenderness should raise suspicion, although fever may be absent in cirrhotic patients. A sudden worsening of ascites or systemic decompensation should prompt further evaluation. Diagnosis is confirmed when the ascitic fluid neutrophil count exceeds 250 cells/mm3, regardless of culture results [95]. Positive cultures usually yield monomicrobial isolates, with over 60% being gram-negative enteric organisms. Gram-positive bacteria account for most of the remainder, while fungal infections account for approximately 5% of cases [96]. Empirical treatment involves third-generation cephalosporins in regions with low multidrug resistance rates. In high-resistance settings, piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem are preferred [97]. Inappropriate antibiotic choice can increase mortality by tenfold [98].

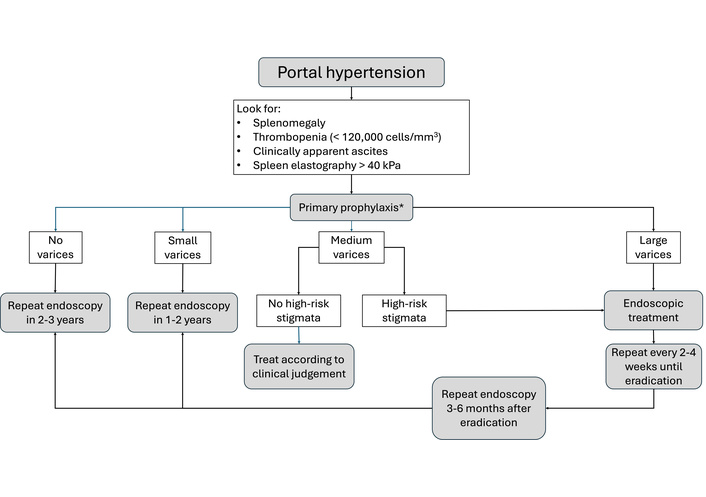

Varices arise from portal-systemic shunting due to elevated portal pressure, resulting in dilation of submucosal veins, most commonly in the esophagus and gastric fundus [99]. In adults, varices develop when HVPG exceeds 10 mmHg, and bleeding occurs above 12 mmHg [100]. However, this relationship is less consistent in children, and HVPG measurement is seldom used in pediatrics because of its invasiveness and limited predictive value [101]. A clinical-based assessment is preferred (Figure 2). Clinically evident portal hypertension (CEPH) is defined by the presence of clinical findings such as splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia and/or at least one clinical manifestation like ascites or varices on endoscopy. “Possible CEPHˮ includes either splenomegaly or thrombocytopenia alone without any manifestation, while “absent CEPHˮ denotes the absence of both [102]. Management involves diagnosing varices in patients with portal hypertension, primary prophylaxis to prevent first bleeding, acute bleeding control, and secondary prophylaxis to prevent rebleeding. Screening in children typically begins when the platelet count is less than 120,000 cells/mm3 and/or spleen elastography exceeds 40 kPa [103]. Unlike in adults, non-selective beta-blockers are currently not recommended for children due to a lack of proven benefit and concerns about bradycardia, vagal response, and adequate dosing, although some renowned centers still use these drugs. A 2021 meta-analysis did not find any randomized trials comparing beta-blockers with other therapies, leaving their effectiveness inconclusive. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the authors found observational studies documenting adverse events. These studies revealed that some patients could not tolerate the treatment due to side effects, with chest pain being the most significant among them [104, 105]. Children with medium-to-large varices or signs of recent bleeding should undergo endoscopic variceal band ligation, which is more effective and safer than sclerotherapy. In infants weighing less than 10 kg, banding may not be feasible, and sclerotherapy is the preferred treatment [103]. Although varices occur in up to 70% of children with biliary atresia [106], bleeding rates are lower than those in adults, occurring in 6–20%, with rebleeding in less than 7% [107]. Mortality rate from variceal hemorrhage is also significantly lower [108]. Acute variceal bleeding management includes volume resuscitation, blood products (Hb target < 9 g/dL), octreotide infusion, proton pump inhibitors, and prophylactic antibiotics [109]. Octreotide (a somatostatin analog) reduces splanchnic flow by inhibiting vasodilation. The usual dosing is a 1 µg/kg bolus followed by a 1–5 µg/kg/h infusion for up to five days [110]. In acute hemorrhage, third-generation cephalosporins reduce mortality, rebleeding, and infection rates [111].

Simplified clinical pathway for the management of gastroesophageal varices. High-risk stigmata: White nipple, red wale marks, cherry red spots, hematocystic spots. *: Some centers adopted the use of carvedilol as primary prophylaxis, though not much literature exists to formally adopt this practice, and its use is left to the clinician’s judgment.

HRS is a type of functional renal failure observed in cirrhosis, characterized by significant renal hypoperfusion without structural kidney disease. It arises from splanchnic vasodilation, decreased systemic vascular resistance, and activation of vasoconstrictor systems, which lead to renal vasoconstriction and reduced glomerular filtration [112]. Unlike classic pre-renal azotemia, HRS does not improve with fluid resuscitation. It is classified into type 1, which progresses rapidly and is often triggered by an acute event, and type 2, which progresses slowly and occurs spontaneously. Diagnostic criteria include a rise in serum creatinine of > 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or a > 50% increase from baseline within 7 days. Supporting findings, such as low urine sodium, bland urinary sediment, and oliguria, help distinguish HRS from other causes of acute kidney injury [113]. Initial treatment involves volume support, blood pressure stabilization, and avoidance of nephrotoxic agents. Terlipressin combined with albumin has been shown to improve renal function more effectively than other vasopressors. Treatment success was defined as a ≥ 30% reduction in serum creatinine with clinical stabilization [114, 115]. Nonetheless, many patients eventually require renal replacement therapy until transplantation becomes feasible [116].

Decompression of the portal venous system through surgical shunting or TIPS is a viable intervention for carefully selected patients. While TIPS is commonly used in adults with decompensated cirrhosis and stable liver function to prevent complications [117], its use in children remains limited. A meta-analysis of TIPS in 198 pediatric patients (ages 6 months to 18 years; weights 6.4–90.6 kg) demonstrated that the technique is feasible even in small children. TIPS placement was successful in 94% of cases, with 91% achieving a reduction in the portosystemic pressure gradient to below 12 mmHg. The main indications were refractory ascites and intractable gastrointestinal bleeding. Long-term follow-up (up to 12.5 years) revealed an 88% survival rate, with approximately one-third of patients requiring liver transplantation. Shunt dysfunction was reported in 27% of patients, although early dysfunction (< 3%) was rare [118]. TIPS has also been used anecdotally for treating HRS, with some success reported, although the evidence base remains insufficient for formal recommendations [119].

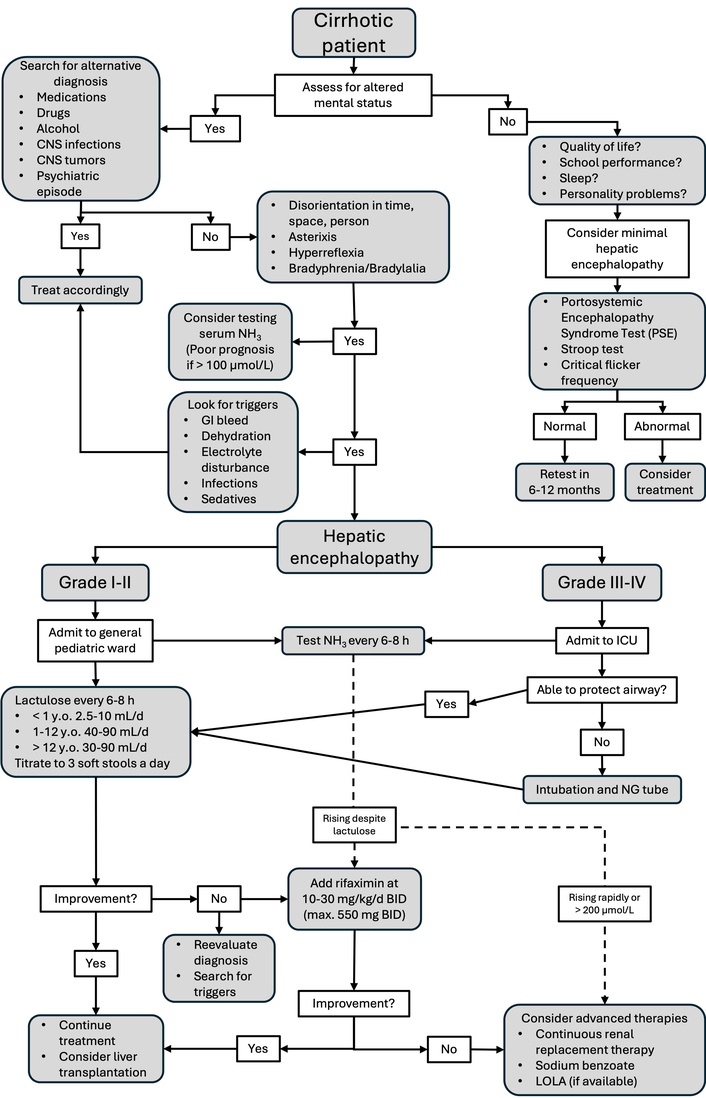

HE arises from the buildup of neurotoxic substances, primarily ammonia, originating in the gastrointestinal tract. These substances either fail to be cleared by the liver due to hepatic dysfunction or enter the systemic circulation through portosystemic shunts [120]. Unlike the acute, severe encephalopathy observed in liver failure, HE in cirrhotic patients is generally chronic and subtle, posing a particular challenge for diagnosis in children [121]. Clinically apparent HE can be identified using the West Haven Criteria, which evaluates consciousness and alertness levels, emotional regulation, orientation in time and space, sleep pattern changes, and osteotendinous reflex characteristics. These criteria not only facilitate the diagnosis of HE but also categorize its severity into grades I to IV and provide alternative criteria for children under 4 years of age [122] (Figure 3).

Simplified clinical pathway for the management of hepatic encephalopathy. CNS: central nervous system; NG: nasogastric; LOLA: L-ornithine L-aspartate.

Measuring blood ammonia can assist in diagnosing acutely ill patients, although it is less informative in chronic cases. A cutoff value of 75 µmol/L has demonstrated reasonable sensitivity for distinguishing HE from other encephalopathic conditions [123]. However, no laboratory marker, including ammonia, reliably correlates with the clinical grade (I–IV) or therapeutic response. Encephalopathy often progresses spontaneously or is triggered by factors such as infections or gastrointestinal bleeding [124]. Treatment aims to reduce intestinal ammonia production and absorption, utilizing lactulose, a non-absorbable disaccharide that acidifies the colon and promotes ammonia trapping, and rifaximin, a gut-selective antibiotic that suppresses urease-producing bacteria [120]. The treatment goal is to achieve the passage of three soft stools daily, avoiding severe diarrhea to prevent hydroelectrolytic imbalances. In pediatrics, minimal HE (grade 0 HE) is of particular concern. It lacks overt clinical signs but is associated with neurocognitive impairments such as decreased attention span, excessive daytime sleepiness, and academic difficulties. Minimal HE is estimated to occur in > 50% of children with chronic liver disease [125, 126]. These deficits can significantly impact school performance and neurodevelopment. Diagnosing minimal HE remains challenging, and various tests have been attempted with different levels of success. Simple tests like the animal naming test, Stroop test, and critical flicker frequency have been used, but they either lack sensitivity, are unsuitable for young children due to the required level of neurological development, or necessitate specialized equipment [127, 128]. A promising alternative is the Portosystemic Encephalopathy Syndrome Test (PSE), developed by German scientists and now adapted for multiple languages and age groups. It assesses functions such as attention, accuracy, working speed, and visual orientation. The primary limitation of PSE is the requirement for trained personnel to administer it, making it unsuitable for bedside use [129]. Although lactulose and probiotics have demonstrated some benefits in prophylaxis, especially given their safety profiles, the current evidence is of low quality, indicating a need for further research before definitive recommendations can be established [130].

Initially characterized as pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with portal hypertension, PoPH now encompasses patients with portosystemic shunts, reflecting a deeper understanding of its pathophysiology. The underlying mechanism involves the exposure of the pulmonary vasculature to unmetabolized vasoactive substances that bypass hepatic clearance [131], leading to arterial wall remodeling. The diagnostic criteria for PoPH include a triad of mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) > 20 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure < 15 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units [132]. These substances trigger remodeling of the pulmonary vessels and right ventricular hypertrophy. Management primarily involves pharmacologic vasodilation, often employing a combination of endothelin receptor antagonists (e.g., bosentan), phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil), and prostacyclin analogues (e.g., epoprostenol). Combination therapy has been shown to be more effective than monotherapy [133, 134]. Unfortunately, these treatments generally stabilize the condition rather than cure it, mainly serving as a bridge to liver transplantation. Severe PoPH (mPAP > 50 mmHg) is associated with a mortality rate nearing 100%, whereas moderate PoPH (mPAP 35–50 mmHg) has an approximate 50% mortality rate [135]. Despite these risks, liver transplantation may be considered in carefully selected patients with well-controlled pulmonary pressure [136, 137]. Regrettably, pulmonary arterial hypertension rarely returns to normal after liver transplantation.

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is characterized by arterial hypoxemia in patients with liver disease caused by intrapulmonary vascular dilation. These dilations permit deoxygenated blood to bypass the alveolar capillary interface, resulting in right-to-left shunting. Unlike PoPH, HPS arises from pulmonary vasodilation rather than hypertension. Clinical suspicion is raised when oxygen saturation falls below 96% in the upright position (orthodeoxia). Some patients experience platypnea, which is dyspnea that worsens when standing and improves when lying down, helping to differentiate HPS from cardiac or primary pulmonary diseases [138]. Diagnosis relies on the triad of underlying liver disease, an alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient greater than 15 mmHg, and evidence of intrapulmonary shunting via contrast-enhanced echocardiography or a 99mTc-macroaggregated albumin lung perfusion scan [139]. The only definitive treatment is liver transplantation, which typically resolves hypoxemia. Although some patients require prolonged postoperative oxygen support, this does not seem to significantly impact hospital or ICU length of stay or overall outcomes [140].

Malnutrition in pediatric cholestasis is a complex, multifactorial issue stemming from the interplay of chronic liver dysfunction, increased metabolic demands, poor intake, portal hypertension-related enteropathy, and endocrine disturbances [141]. In children, malnutrition is particularly harmful due to the limited window for growth and neurodevelopment, leading to long-term consequences if not promptly addressed. The central role of the liver in nutrient metabolism means that hepatic dysfunction significantly impairs the digestion, absorption, storage, and utilization of essential nutrients. Additionally, sarcopenia, a recognized complication of chronic liver disease, is associated with poorer outcomes both pre- and post-transplant. It also promotes alternative metabolic pathways that increase systemic ammonia, fat oxidation, and peripheral glucose levels [142, 143]. Children with cholestatic liver disease often exhibit poor dietary intake due to anorexia, early satiety, and altered taste perception. These issues are linked to elevated tryptophan levels, which enhance brain serotoninergic activity, leading to satiety [144], the presence of proinflammatory cytokines causing nausea and reduced appetite [145], and chronic pruritus, which impairs the quality of life and desire to eat [146]. Moreover, energy expenditure is elevated in this population, likely due to bile acid-mediated activation of intracellular thyroid hormones, requiring up to 150% of age-predicted caloric intake in advanced disease [147, 148].

Effective management necessitates collaboration with a nutrition team well-versed in liver disease. Energy requirements must be meticulously evaluated and fulfilled, with particular emphasis on macronutrients and micronutrients [149]. Fat malabsorption frequently occurs due to diminished bile salt availability for micelle formation. Supplementation with medium-chain triglycerides is advised because they are absorbed without bile salts and transported directly to the liver via the portal vein [150]. Fat should constitute 25–30% of total caloric intake, with adjustments made based on suspected fecal loss. However, they lack essential fatty acids, necessitating separate monitoring and supplementation of EFAs [151, 152]. Cirrhotic children require 130–150% of the age-appropriate protein intake to offset catabolism and reduced hepatic protein synthesis. Traditional markers like albumin and pre-albumin may appear falsely low due to hepatic dysfunction or systemic inflammation, complicating accurate protein status assessment [153]. Particular attention must be paid to vitamins and micronutrients, including fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and zinc.

Vitamin A, stored in the liver, becomes depleted as the disease progresses, potentially leading to xerophthalmia or night blindness. Diagnosis is confirmed through serum retinol levels, and supplementation with 5,000–10,000 IU/day is generally effective [154]. Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent, manifesting as rickets, osteopenia, or osteoporosis. Supplementation typically ranges from 2,000–5,000 IU/day or 50,000 IU weekly, although protocols vary by center [155]. Vitamin E circulates within lipoproteins, so serum levels may appear falsely normal. The vitamin E:cholesterol ratio is a more reliable marker, with a cutoff of 5.9 µmol/mmol being sensitive for diagnosis. Deficiency can result in neurological symptoms that may be irreversible despite adequate treatment, as well as hemolytic anemia with acanthocytosis. Vitamin K is absorbed via chylomicrons and metabolized in the liver for clotting factor activation [156, 157]. Coagulation studies, particularly INR, are used to infer deficiency, although they may be affected by liver dysfunction. Standard supplementation is 2–10 mg/day, preferably administered orally. Intravenous forms may be used in emergencies but carry a risk of anaphylactic reactions [158]. Zinc levels are often low due to reduced albumin binding, with clinical signs of dermatitis and chronic diarrhea. Since serum levels may be misleading, low alkaline phosphatase levels may suggest a deficiency. Supplementation is administered at 1–2 mg/kg/day but is limited by gastrointestinal tolerance [159].

Although rare in children compared to adults, HCC is one of the most severe complications of pediatric cirrhosis. In children, HCC is often linked to underlying chronic liver diseases that lead to cirrhosis, particularly genetic and metabolic disorders, such as tyrosinemia type I, GSDs (types I and III), Wilson disease, and PFIC. Chronic hepatocellular injury and regeneration foster a pro-oncogenic environment that encourages malignant transformation [160]. Unlike adults, where chronic viral hepatitis B and C are the main causes of HCC [161], pediatric cases arise from congenital or hereditary liver conditions, often appearing earlier. Although the incidence of HCC in children with cirrhosis remains low, it is higher in specific high-risk subgroups, necessitating targeted surveillance [160]. Early detection of HCC in cirrhotic children is challenging due to nonspecific clinical presentations and limitations of diagnostic tools. Surveillance protocols include regular abdominal ultrasonography and serum alpha-fetoprotein measurements; however, these methods may lack sensitivity and specificity in pediatric populations, with no universal screening guidelines for children [162]. Imaging findings can be confounded by regenerative or dysplastic nodules in cirrhotic livers, complicating the distinction from early neoplastic changes. Early identification is crucial, as curative treatments like surgical resection or liver transplantation offer better prognoses when detected early. Liver transplantation remains vital for children with underlying liver failure or unresectable tumors within transplant criteria [163]. Although surgery is the primary curative treatment, interest in systemic therapies for advanced pediatric HCC is growing as new molecular and immunologic targets emerge. Although data on children are limited, immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 pathways, has shown promise in adult HCC and is being evaluated in clinical trials. The role of immunotherapy in pediatric HCC remains investigational; however, findings suggest potential benefits in select patients with advanced disease who are unsuitable for surgery or transplantation. Further research is needed to understand the safety and outcomes of these therapies in children [164, 165]. Prognosis is poor if diagnosed late or if metastases are present. However, outcomes have improved due to advances in imaging and treatment. Multidisciplinary management is essential for children at risk of HCC, and team collaboration ensures timely diagnosis and optimal therapeutic strategies.

As illustrated throughout the text, therapies for cirrhotic patients primarily aim to either address the underlying disease to halt or potentially reverse its progression or to manage its consequences and complications. Unfortunately, there are currently no approved treatments specifically for the direct management of fibrosis; however, some medications have shown promising results. One such treatment is the newly approved ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor (IBATi). These drugs function by blocking the reabsorption of bile acids in the ileum, thereby reducing their return to the liver through enterohepatic circulation and promoting their excretion through the stools. As the liver cannot synthesize sufficient bile acids to compensate for this increased loss, there is a net decrease in their systemic concentration. These inhibitors have been developed to treat pruritus in cholestatic diseases, such as Alagille syndrome [166], PFIC [167], and primary biliary cholangitis [168]. Although there is no formal evidence in the current literature, it has been shown that the accumulation of bile acids in the liver parenchyma has many deleterious effects, and improving cholestasis—and therefore bile acid retention—may have beneficial effects on liver health [169, 170]. Consequently, the use of IBATi may delay or even improve fibrosis, which could, in turn, have an overall positive impact on patient survival [171]. However, more evidence is needed to make formal recommendations.

Directly targeting liver fibrosis offers a promising therapeutic strategy, although the results have been inconclusive due to the complexity of its pathophysiology. Beyond drugs that protect hepatocytes from damage or modulate the inflammatory response, there are two main theoretical targets: (1) inhibition of hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and (2) reduction of fibrosis deposition. HSCs are usually in a quiescent state but can be activated by cytokines, such as TNF-α, TGF-β, and various interleukins [172]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), especially the γ isoform (PPARγ), play a crucial regulatory role in metabolism and homeostasis, and their expression decreases HSC activation. Pioglitazone, an insulin-sensitizing PPARγ agonist, has shown effectiveness in improving liver fibrosis in MASH, while elafibranor, a dual PPAR α/γ agonist, has demonstrated improvement in fibrosis in murine models [173, 174]. Trials are currently underway, but these treatments have not yet been approved for fibrosis in adults or children. Another therapy in use is fenofibrate, employed as a second-line treatment for primary biliary cholangitis, with mixed results; it seems to improve liver biochemistry but does not appear to affect long-term outcomes [175]. However, no pediatric indication exists to date. FXR, which binds to bile acids, inhibits collagen production in HSCs. Obeticholic acid, an FXR agonist, has demonstrated potential for improving fibrosis in patients with diabetes and MASLD. An interim analysis of an ongoing phase 3 trial indicated that it improved fibrosis by at least one stage. Recently, it has been approved for the treatment of adults with primary biliary cholangitis who have not responded to UDCA [176].

Lysyl oxidase-like 2, an amine oxidase secreted by HSC, stimulates collagen deposition by facilitating collagen cross-linking. While its inhibition has shown promise in murine models, the monoclonal antibody simtuzumab has not been effective in treating fibrosis in PSC human patients [177]. Another therapy under investigation aims to reduce collagen deposition by interfering with RNA synthesis. Heat shock protein 47, a chaperone crucial for collagen production in the endoplasmic reticulum, has demonstrated potential in reducing fibrosis stages through the use of interfering RNA, and human trials are currently ongoing [178].

Diagnosing and monitoring pediatric cirrhosis presents significant challenges, primarily because the current gold standard is a liver biopsy. This procedure has several drawbacks, such as its invasive nature and the risk of complications, particularly when multiple biopsies are required over time. Additionally, the findings can sometimes be imprecise because of the typically heterogeneous nature of liver damage [179]. Consequently, non-invasive methods for assessing fibrosis are highly sought after, not only for diagnosis but also for tracking its progression. In adult settings, many new modalities for studying liver fibrosis have shown promising results, including elastography (using either ultrasound or magnetic resonance) and biochemical scores like APRI or Fib-4 [180]. Unfortunately, in pediatric settings, the use of liver stiffness measurement through elastography has produced inconsistent results. While it appears effective in distinguishing patients with advanced fibrosis from those without, it is less useful for differentiating between various degrees of fibrosis, making it less effective for follow-up [181]. Similar findings have been reported for the use of Fib-4 or APRI, as they show varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity in identifying advanced fibrosis, but they do not outperform the simple evaluation of platelet numbers over time [182].

Researchers are currently investigating new markers in both adult and pediatric populations. One promising marker, cytokeratin 18 fragments in serum, shows potential for detecting fibrosis. These fragments, which are intermediate filament proteins, are released into circulation following cell death and have been used to assess the progression of hepatocyte injury and fibrosis. This marker has shown potential in diagnosing and monitoring children, although it is not widely accessible, and no formal recommendations have been issued yet [183]. MicroRNAs are short regulatory RNA molecules that interfere with gene expression, and their deregulation has been observed in various liver diseases. Among them, miRNA-122 is linked to collagen deposition in liver samples and has been shown to negatively correlate with the degree of liver fibrosis [184]. This suggests it could be a promising non-invasive marker, although further evidence is required for its use in clinical settings. Three other known markers of liver fibrosis—hyaluronic acid, procollagen III N-terminal peptide, and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1—are used in the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score, which employs an algorithm to determine the presence of significant and advanced fibrosis, like Fib-4. However, the former appears to have higher accuracy in diagnosing patients with cirrhosis, making it a useful non-invasive marker of liver fibrosis. Unfortunately, there is no solid evidence to recommend its use in the pediatric population [185].

Long-term outcomes for pediatric patients with cirrhosis hinge entirely on factors such as etiology, timeliness and severity of diagnosis, availability of medical and/or surgical treatments, and potential for liver transplantation. While conditions like Wilson disease, HBV, HCV, and AIH are familiar to adult hepatologists, certain conditions deserve special mention as they have traditionally been managed almost exclusively in pediatric settings. Biliary atresia is the leading cause of pediatric cirrhosis and liver transplantation. Outcomes are directly tied to early detection and timely Kasai portoenterostomy, with significant differences observed between procedures performed before or after 60 days of age [186]. Nonetheless, even patients with a functional Kasai procedure typically develop cirrhosis over time and will require liver transplantation, with some authors reporting long-term native liver survival rates between 20–60% at 20 years of age, with improvements noted in the last decade [187]. Conversely, pediatric patients who undergo timely transplantation generally achieve excellent long-term survival rates exceeding 90% at 10–20 years post-transplant. However, complications such as cholangitis, vascular or biliary lesions, growth retardation, and issues related to long-term immunosuppression are common and may affect the patient’s quality of life [188].

In patients with PFIC, the specific type of disease greatly affects both native liver survival and post-transplant outcomes. A recent study reported an average age of 2.93 years at the time of transplantation [189]. Patients with FIC-1 often develop cirrhosis within the first decade of life, leading to the need for liver transplantation before adulthood in up to 70% of cases. There is optimism that new medications could delay the need for transplantation by addressing pruritus, a primary concern, or by improving overall liver health [190]. Post-transplant survival rates are similar to those of most other diseases, with > 90% of patients surviving beyond 10 years. However, it is crucial to note that most extrahepatic symptoms do not improve after transplantation, with ongoing issues such as diarrhea, growth failure, and hearing loss. In cases of BSEP deficiency, native liver survival is poorer, with fewer than 20% of patients reaching adulthood without transplantation. The rapid progression of cirrhosis and development of HCC are the main reasons for transplantation. Biliary diversion, whether surgical or medical, can help manage cholestasis and pruritus, although responses are more variable than those in FIC-1 cases [191, 192]. Finally, patients with MDR3 deficiency show the best native liver survival, with over 60% surviving 10 years post-diagnosis, and many never require a transplant [191].

Alagille patients require special attention, as extrahepatic complications contribute to overall mortality, regardless of liver transplantation. An analysis of the natural history within the GALA cohort revealed that native liver survival was approximately 40% by the age of 18 years, with over 50% of patients having already undergone transplantation. Notably, more than 70% of these transplants are performed within the first five years of life, primarily to address refractory cholestasis and its complications. It is important to note that during childhood, 20% of deaths were attributed to cardiac disease, whereas 15% resulted from noncardiac and multiorgan failure [193]. There is a lack of clear information regarding non-hepatic mortality in adult Alagille patients, with survival rates ranging from 25–60%, depending on the presence and type of cardiac abnormality [194, 195]. Furthermore, it must be considered that these patients may eventually become “too sick” for transplantation, similar to what occurs in patients with FALD. With the improved management of CF pulmonary disease through CFTR modulators, CFLD has emerged as a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in patients, accounting for up to 2.5% of cases [30]. The severity of liver disease directly impacts survival, as evidenced by a recent study showing that 26.4% of children either died or required a transplant during a 10-year follow-up period [196], with a median age at death of 24 years [197].

In cases of GSD type I, patients typically experience a smooth natural history when good metabolic control is maintained, with a 20-year survival rate of approximately 100% [198]. However, the development of adenomas is common, with a prevalence ranging from 20–75%, and transformation into HCC occurs in 5–10% of long-standing cases, necessitating regular surveillance [199]. The physiopathology of GSD III makes cirrhosis development a significant aspect of its natural progression, with up to 40% of patients developing it by the age of 40 years. Moreover, HCC can develop even in the absence of adenomas or cirrhosis, requiring lifelong follow-up [200]. GSD IV is generally more aggressive, with most patients undergoing transplantation before adulthood, leading to complications arising from transplantation rather than cirrhosis. It is important to note that some patients may present later with muscle, cardiac, and even nerve involvement, and these patients also seem to benefit from liver transplantation [201].

Transitioning to adult care poses challenges in many chronic diseases, particularly those in which therapies have significantly extended life expectancy into adulthood, presenting adult hepatologists with conditions they have not previously encountered. This is especially true for pediatric cirrhosis, as many diseases traditionally fall within the pediatric realm, as discussed in this article. Like other settings, a successful transition depends on clear communication of essential information, such as complications, treatments, and patient adherence to medical recommendations. Transition planning should commence early, typically at the age of 12 years, but must be tailored to the patient's mental and emotional maturity. Ideally, patients should have a clear understanding of their condition and the treatments they have received, while also taking responsibility for scheduling follow-ups, managing prescriptions, and recognizing warning signs that require a consultation. The transition of care should be managed by a multidisciplinary team, including pediatric and adult hepatologists, nutritionists, social workers, and transplant coordinators, when applicable. The transition period is associated with an increased risk of complications, loss of follow-up, or lapses in treatment adherence; therefore, both teams must do everything possible to ensure efficient continuation of care [202].

The management of pediatric cirrhosis necessitates a multidisciplinary and personalized approach that acknowledges the varied underlying causes, disease progressions, and complications. Early etiological diagnosis achieved through genetic, metabolic, and immunological investigations facilitates targeted interventions and improves prognosis. Essential components of care include nutritional optimization, management of portal hypertension, recognition, prevention, and treatment of HE, timely referral for liver transplantation, and adequate transition to adult care. Optimal care requires the integration of hepatologists, transplant surgeons, pediatric gastroenterologists, nutritionists, and psychosocial professionals to ensure a comprehensive approach to the physiological and developmental challenges of pediatric liver disease. Future research into molecular mechanisms, novel pharmacotherapies, and long-term outcomes will be vital for improving the survival and quality of life of children with chronic liver conditions.

A1AT: alpha-1 antitrypsin

AIH: autoimmune hepatitis

BSEP: bile salt export pump

CEPH: clinically evident portal hypertension

CF: cystic fibrosis

CFLD: cystic fibrosis-associated liver disease

CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

FALD: Fontan-associated liver disease

FXR: farnesoid X receptor

GSDs: glycogen storage diseases

HBV: hepatitis B virus

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV: hepatitis C virus

HE: hepatic encephalopathy

HPS: hepatopulmonary syndrome

HRS: hepatorenal syndrome

HSC: hepatic stellate cell

HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient

IBATi: ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor

IFALD: intestinal failure-associated liver disease

MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure

PFIC: Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

PoPH: porto-pulmonary hypertension

PPARs: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis

PSE: Portosystemic Encephalopathy Syndrome Test

SAAG: serum-ascites albumin gradient

SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts

UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid

GAC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Validation. FÁ: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Validation. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

GAC is a medical advisor for Mirum Pharmaceutics and Medison Pharma. GAC is also a PI in a clinical trial with Pfizer. FÁ has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 3007

Download: 100

Times Cited: 0

Andrew Johnson, Shahid Habib

Thierry Thevenot ... Hilary M. DuBrock

Paul Carrier ... Laure Elkrief

Balasubramaniyan Vairappan ... Mukta Wyawahare