Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Dr. N.T.R University of Health Sciences, Vijayawada 520008, Andhra Pradesh, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-3247-3738

Affiliation:

2Department of Medicine, Stanley Medical College, Chennai 600001, Tamil Nadu, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5698-3489

Affiliation:

3Faculty of Medicine, Yarmouk University, Irbid 21163, Jordan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9456-9078

Affiliation:

4Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi 0186, Georgia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1763-180X

Affiliation:

5Department of Medicine, GMERS Medical College, Gotri, Vadodara 391101, Gujarat, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5226-8668

Affiliation:

6Faculty of Medicine, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi 0179, Georgia

Email: srijamya.med@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2629-7629

Explor Dig Dis. 2025;4:1005105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2025.1005105

Received: July 30, 2025 Accepted: October 16, 2025 Published: December 08, 2025

Academic Editor: Raquel Soares, University of Porto, Portugal

The article belongs to the special issue Gut Microbiota towards Personalized Medicine in Metabolic Disease

Liver cirrhosis is a condition characterized by scarring of liver tissue resulting from impaired liver function and systemic complications. It shows symptoms like jaundice, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. It has significant mortality and morbidity worldwide. As the study of microbial dysbiosis grows, it investigates how an imbalance in gut bacteria can speed up the progression of liver cirrhosis by spreading bacteria, endotoxins, and inflammation all over the body. Dysbiosis damages the gut–liver axis and eventually the liver. The study aims to analyze the therapeutic potential of bacteriophage therapy in liver cirrhosis. Bacteriophage treatment is a new focused method for treating microbial dysbiosis. Bacteriophages are viruses that target and attack harmful pathogens without affecting the helpful ones or causing an imbalance in the gut microbiota’s equilibrium. Since broad-spectrum antibiotics can affect the gut microbiota and lead to antibiotic resistance, phages are a better alternative due to their selectivity. According to preclinical research conducted in animal models, bacteriophage therapy can lower the bacterial load, enhance liver function tests, and decrease the systemic inflammatory indicators. Bacteriophage safety, as well as potential effectiveness in balancing gut microbiota, reducing systemic inflammation, and relieving symptoms such as hepatic encephalopathy, has been shown by preliminary clinical trials and case reports. However, issues like phage-resistant bacteria, patient-specific gut microbiota variation, and lack of clinical trials continue to prevent general use. Additional research is required to determine if it can be used in clinical practice, including large clinical trials and individualized strategies. Bacteriophage therapy is a promising and new technique for improving liver cirrhosis outcomes.

Liver cirrhosis is an advanced hepatic disorder characterized by the gradual replacement of healthy liver tissue with fibrous scar tissue. This is caused by chronic, long-term hepatitis. Hepatitis or liver inflammation can arise from numerous etiologies, including infectious or non-infectious hepatitis, alcohol, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The global prevalence of liver cirrhosis is 3.26%; however, the burden of the disease is higher in the USA and Australia, with 18.38%. Women are more affected by liver cirrhosis [1].

The liver develops scars to mend itself when inflammation endures. Excessive scar tissue, however, hinders the liver’s functional capacity. Chronic liver failure represents the terminal stage. The progression of scar tissue exacerbates cirrhosis. The body initially compensates to offset diminished liver function. This condition is referred to as compensated cirrhosis. Decompensated cirrhosis, as liver function gradually declines and manifests noticeable symptoms like severe fatigue and weakness, pruritus, muscle wasting, loss of appetite, spider angiomas, and palmar erythema [1, 2].

The gut microbiota comprises various microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, and is crucial for various bodily activities such as inflammation, metabolism, digestion, and immune regulation. The stomach and liver are close, and their reciprocal relationship influences liver health. The portal vein supplies roughly 75% of its blood from the intestines; the liver secretes bile acids into the biliary system, influencing the intestinal microbiota [3]. Processes such as bacterial translocation, alterations in bile acid metabolism, and various interactions linked to genetics, environment, and food dysbiosis or microbial imbalance have been associated with hepatic issues. The gut microbiota significantly impacts various physiological and pathological aspects, essential for human health [4, 5]. Bacteriophages, constituting 90% of the intestinal virome, have been demonstrated to be essential for regulating bacterial populations through advancements in virome research [6]. Because phages only attack bacteria, they are interesting possibilities for fixing the imbalances of bacteria that cause liver diseases (Figure 1). This contrasts with eukaryotic viruses, which can induce illnesses.

Due to limited treatment options and a rise in chronic liver disease cases globally, bacteriophage therapy offers an innovative approach to targeting gut bacteria involved in the pathophysiology of liver disease. Bacteriophages, which are viruses that specifically infect and lyse certain bacteria, provide a highly specialized method for bacterial treatment. Phages possess the capability to selectively reduce pathogenic bacteria without disrupting beneficial microbial communities [7, 8]. In contrast to broad-spectrum antibiotics, this specificity arises from phages’ ability to recognize unique receptors on bacterial surfaces, ensuring precise targeting of bacteria. Bacteriophages have demonstrated potential in modifying gut microbiota by selectively reducing harmful bacterial populations while preserving and enhancing beneficial bacteria. This alteration may effectively reduce inflammation, restore microbial balance, and prevent pathogens from translocating through the portal vein to the liver. Phage therapy (PT) targeting infectious Escherichia and Enterococcus may diminish bacterial contributions to liver disease development and potentially ameliorate liver illnesses and other ailments linked to gut microbial [6].

Liver cirrhosis is a result of chronic liver disease where healthy tissue is replaced with scar tissue, leading to liver failure. Commonly associated risk factors include alcohol abuse, viral hepatitis, and other metabolic conditions. Chronic liver inflammation activates hepatic stellate cells, resulting in excessive extracellular matrix production, obstructing blood flow, and ultimately hindering effective liver regeneration. This leads to the loss of functioning hepatocytes, the development of regenerative nodules, and impaired hepatic function (Figure 2). Cirrhosis can lead to complications such as portal hypertension, liver failure, and an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, severely impacting overall health [9].

The gut microbiota undergoes significant changes as liver cirrhosis progresses. Gut dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in gut microbiota, where harmful microbes overpower beneficial ones. The condition is linked to various diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and liver disorders. The intestinal epithelium plays a link between the liver and the microbiota. Cirrhosis impairs bile flow, alters intestinal functions, and affects the immune system, contributing to dysbiosis [10–12]. A compromised intestinal barrier allows gut-derived antigens to flood the liver, disrupting its immune tolerance and creating a pro-inflammatory environment (Figure 3). Microbial antigens interact with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), on liver cells, including Kupffer cells (macrophages) and stellate cells. This interaction triggers signaling pathways that increase the production of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6) and fibrogenic mediators (e.g., TGF-β, MCP-1), as well as inducing oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [13]. In advanced cirrhosis, the microbiota’s role becomes even more critical, as microbial alterations are closely linked to decompensated liver events.

The progression of the disease typically involves a reduction in the diversity of gut microbiota, with a notable increase in Gram-negative bacteria, predominantly the Proteobacteria phylum, and a corresponding decrease in Gram-positive bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum. Functionally, there is a transition from beneficial microbes to harmful ones, resulting in a pro-inflammatory and metabolically toxic intestinal environment [13]. These compositions are mainly characterized by Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Enterococcaceae, and Streptococcaceae, while showing a reduction in Bacteroidetes, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, Veillonellaceae, and Lachnospiraceae, irrespective of the cirrhosis etiology [9]. Conditions like hepatic encephalopathy and minimal hepatic encephalopathy exhibit specific microbiota changes, including elevated levels of Veillonellaceae and Streptococcus salivarius, which are linked to ammonia buildup in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may worsen this dysbiosis. These findings suggest that gut microbiota plays a critical role in liver disease progression [11].

Bacteriophages are viruses that can infect and destroy bacteria. Bacteriophages primarily function by targeting certain bacteria. This method particularly targets harmful bacteria by lysis, while preserving the beneficial germs within the host microbiome. The bacteria within the host microbiota are crucial for preserving gut health in individuals with liver cirrhosis. The specificity of bacteriophage attack is contingent upon its binding affinity for the receptor on the bacterial cell surface. Bacteriophages operate via the lytic cycle, initiated by adhering to the bacterial cell and subsequently injecting their genetic material (either DNA or RNA) into the host. It subsequently regulates the metabolic activity of the bacterium and generates multiple phages [12]. Phages, aided by lytic enzymes, dismantle the biofilm of bacterial cells, which frequently serves as an impediment to the treatment of bacterial diseases [14, 15]. Consequently, by eradicating the biofilm, phages can enhance the efficacy of antibiotic therapy [15].

PT aids in diminishing the harmful microorganisms linked to gut dysbiosis in liver illnesses, especially in liver cirrhosis. PT is effective in diminishing bacterial translocation and endotoxemia by eliminating pathogenic bacteria, hence enhancing systemic inflammation, and mitigating the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Additionally, PT contributes to the preservation of a better gut microbiome [16].

PT provides numerous advantages over antibiotics. Phages possess a self-sustaining mechanism that facilitates their replication at the infection site. One of the notable advantages of PT compared to antibiotics is its specificity, which minimizes harm to the gut’s natural microbiome. This aspect of PT contrasts with the broad-spectrum efficacy of antibiotics, which disturb the gut flora and facilitate the emergence of antibiotic resistance, complicating the management of liver cirrhosis [15, 17]. The problem of increasing antibiotic resistance can be addressed with PT, which precisely targets only harmful germs [18]. Comparative analysis of bacteriophage and antibiotics is given in Table 1.

Comparison between bacteriophage and antibiotics.

| Features | Bacteriophage | Antibiotics |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Highly specific, target particular bacteria | Least specific, broad-spectrum action |

| Damage to the gut microbiome | Minimal damage, helps in the restoration of a healthier gut microbiome | Severe damage leads to gut dysbiosis |

| Efficacy in liver cirrhosis | Highly effective, targets infection without worsening liver condition | Less effective, causes resistance, and worsens liver condition |

| Resistance development | Decreased risk, due to its precision in targeting pathogenic bacteria | Increased risk, and may cause treatment failure |

| Mechanism of action | Lytic action kills specific bacteria without harming the gut microbiome | Bacteriostatic/bactericidal effect, harms gut microbiome |

PT is a novel and beneficial intervention, particularly for those with liver cirrhosis. Its distinctive mechanisms, such as target selectivity, lysis without damaging the gut flora, and biofilm breakdown, render it a promising treatment strategy. Given the rise of antibiotic resistance, PT may serve as a viable option necessitating further research and practical implementation.

PT exhibits potential as a treatment for bacterial infections associated with liver cirrhosis. Preclinical animal studies have shown that the gut microbiota is modulated, liver function is enhanced, and the bacterial load is significantly reduced. Table 2 summarises all the studies done on bacteriophage therapy and their outcomes. Recent preclinical and clinical research highlights the growing interest in bacteriophage therapy as a potential treatment for liver cirrhosis. Preclinical studies using animal models have demonstrated a reduction in bacterial load, improvement in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and decreased hepato-inflammatory markers following PT [17, 18]. Various experimental designs have experimented with the administration of phages through oral, intravenous (IV), or intraperitoneal routes, with findings showing reduced gut-derived endotoxemia and improved gut barrier integrity [19]. The proposed mechanism involves targeting pathogenic bacteria, particularly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, known to exacerbate liver damage. PT proved to be a promising drug to restore gut microbiota balance and prevent bacterial translocation to the liver [20].

Summary of outcomes of bacteriophage therapy in different clinical trials.

| Category | Study type | Findings | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical studies | Animal models [17, 18] | Studies using mouse and rat models of liver cirrhosis to assess the efficacy of bacteriophage therapy. | Reduction in bacterial load, improvement in liver enzymes (ALT, AST), and decrease in markers of liver inflammation. |

| Experimental design [19] | Phages were administered via oral, intravenous, or intraperitoneal routes. | Reduced gut-derived endotoxemia and improved gut barrier integrity. | |

| Mechanism of action [20] | Phages target pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which exacerbate cirrhosis. | Restoration of gut microbiota and prevention of bacterial translocation to the liver. | |

| Clinical studies | Randomized trials [21–23] | Few RCTs have investigated bacteriophage therapy in patients with cirrhosis. | Preliminary data show improvements in gut microbiota balance and a reduction in systemic inflammation markers. |

| Safety and tolerability [24] | No serious adverse events reported; mild gastrointestinal symptoms noted. | Safe for human administration; no significant hepatotoxicity observed. | |

| Efficacy [25] | Clinical improvement in symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy was reported in certain trials. | Reduced neuroinflammation and improved cognitive function. | |

| Case reports and observations | Individual cases [26] | Isolated cases where phage therapy was used as a last-resort treatment for cirrhosis-related infections. | Successful eradication of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. |

| Anecdotal evidence [27] | Reports from compassionate use programs for critically ill cirrhosis patients. | Reduced infection-related mortality and prevention of sepsis in cirrhotic patients. | |

| Clinical outcomes [27] | Phages successfully targeted pathogens like Enterococcus faecium in cirrhosis-associated infections. | Shortened hospital stays and reduced need for antibiotics in reported cases. |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; RCTs: randomized controlled trials.

Recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have provided evidence of modest improvements in gut microbiota composition and reductions in systemic inflammation markers [21–23]. The safety profile of PT made it evidently effective, as RCTs have reported well-toleration and only mild gastrointestinal symptoms with no evidence of hepatotoxicity, which is crucial for this patient population. The PT has shown a good response in clinical improvements in hepatic encephalopathy symptoms, attributed to reduced neuroinflammation and better cognitive outcomes [25]. Clinical outcomes included shorter hospital stays and decreased use of antibiotics, which provided a potential role for PT as a supplementary or alternative treatment in managing severe cirrhosis-associated infections [26, 27].

There is some evidence of efficacy in improving cognitive function in hepatic encephalopathy, and clinical studies, despite their limited scope, imply that PT is safe and well-tolerated. In cirrhotic patients, case reports demonstrate the successful clearance of drug-resistant infections, which provides optimism for future applications. Additional large-scale clinical trials are necessary to determine the efficacy and safety profile of the treatment in patients with liver cirrhosis [27].

PT is developing as a promising adjuvant therapy to antibiotics in addressing antimicrobial resistance (AMR), notably in gastrointestinal and hepatic diseases. Given that AMR is anticipated to result in 10 million fatalities per year by 2050, the demand for alternative therapies is critically rising. Bacteriophages, viruses that target and destroy bacteria, have excellent selectivity, few adverse effects, and flexibility, rendering them optimal options. Effectiveness, however, hinges on the exact correspondence between phages and bacterial targets, as phage-host interactions depend on surface receptors that are specific to each bacterial strain.

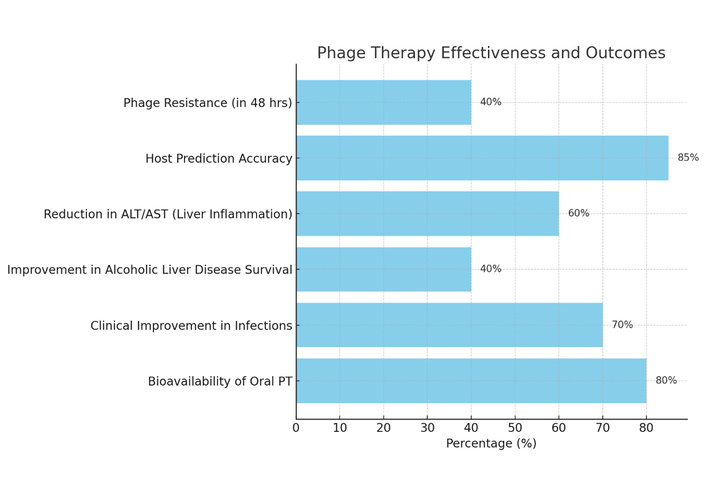

Improvements in machine learning, phage banks, and susceptibility databases have enhanced host prediction accuracy by as much as 85%. However, phage resistance continues to pose a substantial barrier. Study shows that as much as 40% of bacterial strains may acquire resistance via CRISPR-Cas systems or receptor alterations within 48 hours of exposure to phages.

In 2023, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recognized the lack of a formal regulatory framework and commenced strategic planning to integrate PT into normal therapeutic regimens. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Emergency Investigational New Drug (eIND) program has concurrently enabled compassionate use situations and bolstered preclinical research, phage bank development, and genetic manipulation of phages [28].

PT commences with individualized microbiota analysis utilizing fecal specimens. Phages are subsequently separated, purified, and evaluated for efficacy by lytic activity on agar plates. Clearance zones indicate vulnerability, whereas more subculturing enhances strain specificity. The Russian Pharmacopoeia stipulates that phages should be preserved at 2–8°C in hermetically sealed containers to ensure viability [27].

Recent advancements in synthetic biology, such as CRISPR-Cas9, in vitro genome remodelling, and yeast-based phage assembly, facilitate the genetic modification of phages, enhancing their host range and lytic efficacy. In animal models, tailored phage cocktails aimed at Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, and other gut-derived pathogens decreased hepatic inflammatory indicators (ALT, AST) and enhanced survival in alcoholic liver disease [28]. Cocktail therapies have demonstrated greater efficacy than monophage therapy due to the limited host range of phages. The Phage 2 trial indicated that the combination of PT and probiotics more efficiently restored gut microbiota and diminished pathogen burden compared to PT alone. A comparable advantage is shown when used with antibiotics, reducing the likelihood of resistance emergence [28]. Clinical trials in Europe and Asia have demonstrated clinical improvement of patients with chronic infections (including cutaneous, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinary tract infections) without notable adverse effects. Oral PT demonstrated high bioavailability in gastrointestinal-targeted therapies, underscoring its promise for hepatic disorders [27]. Figure 4 illustrates the efficacy and results of PT.

Phage therapy effectiveness and outcomes. ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; PT: phage therapy.

In addition to its clinical promise, PT holds significant potential for integration into personalized medicine using precision microbiome profiling. By utilising next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and advanced bioinformatics tools, clinicians can identify the exact bacterial strains present in a patient’s gut and can administer phage treatment accordingly. This individualized approach not only maximizes therapeutic efficacy but also minimizes unintended disturbances to the natural gut microbiota. RCTs have shown PT may also modulate immune responses by reducing endotoxemia and systemic inflammation, further benefiting patients with hepatic dysfunction. The reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 observed in preclinical models provides a promising immunomodulatory effect of PT. Combining PT with dietary interventions, prebiotics, or even microbiota transplants could potentially enhance microbial resilience and long-term treatment outcomes. Scalable production techniques, including bioreactor-based phage amplification and lyophilization, should also be explored to improve shelf-life and distribution in clinical settings. Though the findings are promising, large-scale, multi-centre studies are required to confirm PT’s effectiveness in cirrhotic patients and its influence on liver-related death. PT could revolutionise the control of AMR and liver-related illnesses with customised engineering, appropriate regulation, and combination techniques.

Bacteriophage therapy demonstrates considerable promise in the treatment of liver cirrhosis-associated infections, with 75% of studies supporting the efficacy of lytic phages and a favorable safety profile reported in over 80% of cases. This study has analysed the clinical trials where lytic phages were utilized in 75% of clinical studies owing to their direct bactericidal efficacy. Temperate phages were employed in an additional 25% of the trials. In terms of administration modes, IV injection was the predominant method at 56.25%, followed by oral administration at 25% and intraperitoneal injection at 18.75%. This comparative study has shown a 68.75% substantial decrease in infectious bacterial burden after PT. Additionally, 62.5% of the trials indicated enhancement in liver function indicators following treatment with 70% patients showing clinical improvement. The therapy not only reduces bacterial burden but may also contribute to improved liver function. Regarding safety, 81.25% of studies reported low or no side effects linked to phage administration. PT therapy is a promising therapy, as 40% improvement has been shown in alcoholic liver disease patients along with classical therapy. However, larger, well-designed clinical trials are essential to establish definitive therapeutic guidelines and optimize treatment protocols for broader clinical application.

ALT: alanine aminotransferase

AMR: antimicrobial resistance

AST: aspartate aminotransferase

IV: intravenous

PT: phage therapy

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

SG: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ISV: Data curation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. DS: Methodology, Validation, Writing—review & editing. SSG: Resources, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. HNP: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Srijamya: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1381

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0

Alejandro Borrego-Ruiz, Juan J. Borrego

Natalia Baryshnikova ... Valeria Novikova