Affiliation:

1Physics Faculty, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 01601 Kyiv, Ukraine

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6793-7947

Affiliation:

1Physics Faculty, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 01601 Kyiv, Ukraine

2Education and Research Institute of Energetics, Automation and Energy Efficiency, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, 01601 Kyiv, Ukraine

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3727-5617

Affiliation:

1Physics Faculty, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 01601 Kyiv, Ukraine

Email: SGNedilko@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5196-6807

Explor BioMat-X. 2025;2:101353 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2025.101353

Received: May 22, 2025 Accepted: December 03, 2025 Published: December 22, 2025

Academic Editor: Esmaiel Jabbari, University of South Carolina, USA

The article belongs to the special issue Nature-Based Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications

Luminescent markers have been widely used in medicine, biology, agrotechnology, and for marking nuclear wastes and consumer goods. The high sensitivity and selectivity of the markers/labels allow the detection of various substances and the obtaining of valuable information about the distribution of constituents in specific media. This review describes the state of the art in luminescent marking/labeling of various cellulose forms, including nanosized ones, cellulose derivatives, and cellulose-containing materials. The importance of this consideration is explained by the role of cellulose and its derivatives in human life and their overall impact on mankind’s development. The structure and luminescence properties of cellulose and other related materials and cellulose derivatives are discussed from the viewpoint of cellulose luminescent “self-labeling”. It is shown that dyes, organic molecules, and organic-inorganic complexes, as well as inorganic dielectric and semiconductor micro/nanoparticles, can be effectively applied for the purposes of cellulose luminescent marking/labeling. This review discusses various application examples and explains the performance and mechanisms of various systems labeling (e.g., dye-cellulose, quantum dot-cellulose complex) in these applications. The review not only comprehensively summarizes existing approaches to luminescent labeling of cellulose-containing materials. It also highlights problematic issues that arise for developers of new luminescent markers (quenching of luminescence in an aqueous environment, the need to functionalize the luminescent marker material, etc.). At the same time, this work demonstrates the prospects for luminescent labeling data in modern digital technologies, particularly in the Internet of Things (IoT).

There is no doubt that the luminescent labeling method has become a much more powerful scientific tool than it was conceived. In fact, among the analytical detection methods, the luminescence ones are characterized by high sensitivity and selectivity. These peculiarities allow the detection of various substances and the obtaining of valuable information about luminescent particles’ distribution in specific media.

Labeling is a part of our everyday life as we mark some things by drawing, sticking, sewing, scratching, etc. A bright label, particularly one seen at low-intensity lighting, can be made using luminescent stickers or inks. Such luminescent labeling has been widely used, e.g., for marking the boxes during transportation. Similar methods have been applied in science and high technologies. However, the materials and tools for luminescent labels are quite specific. In such a case, the luminescent atoms, molecules, or ions play the role of labels and should be “glued”/introduced to the substance that is labeled. The micro/nanoparticles of the luminescent compound incorporated into the structure of another compound (matrix) can also be used as labels. Such a label manifests itself, if needed, under action on the marked substance of energy flow (excitation), e.g., ionizing radiation (gamma and X-ray quanta) or light from vacuum ultraviolet up to visible and infrared spectral regions. The label under excitation can reveal light emission at longer wavelengths (compared with excitation wavelength)—fluorescence, and, in some specific cases, long-lasting luminescence (phosphorescence) can also be detected. Such luminescent marking allows the creation of a map of the sample, or the marked area can be seen even with the naked eye when labels emit light in the visible spectral region. Nowadays, such visualization is a powerful tool in biological and medical studies.

Spectrum (band shapes and positions, intensity), quantum yield, and kinetics (changes in intensity over time after excitation pulse) are the main characteristics of the luminescence. These characteristics of luminescent labels have no interest for the average user; however, they are crucial for scientific studies and high-tech applications. The development of modern microscopy and optical technologies significantly widens the area of luminescent labels’ usage in medicine, biology, agrotechnology, for marking nuclear wastes, consumer goods, etc. Thus, it is unsurprising that numerous studies in the abovementioned branches of science were performed, and the results have been published in original and review papers [1–10]. The various compounds and their combinations/composites were used as luminescent labels in the abovementioned studies. Concerning the objects for labeling, it is worth mentioning the DNA [4–6, 9, 11], proteins/enzymes [12–14], blood [15], media with heavy metal ions [16], nucleic acids [16–20], etc.

In this review paper, we focus attention on the luminescent labeling/marking of various forms of cellulose, namely, microfibrillated (MFC), microcrystalline (MCC), nanocrystalline/nanosized (NC), bacterial cellulose (BC), as well as cellulose derivatives and cellulose-based materials/composites. The relevance of this consideration is due to the role of cellulose and its derivatives in the everyday life of every human and overall impact on mankind’s development [21–31]. It is worth noting that there are numerous cellulose derivatives and cellulose-based materials. All of them have specific composition, structure, and properties (chemical, physical, biochemical, etc.). Therefore, the development of suitable luminescent markers for such diversity of cellulose forms and derivatives attracted significant attention from scientists for a long time. Thus, we describe the most widely used luminescent labels at the beginning of the present review.

Some important data on the chemical composition and structure of cellulose chains and molecules, as well as micro-/nanosized forms of cellulose, such as MFC, MCC, NC, and BC, will be described in the second part (Cellulose forms and structures) of this work. The methods and procedures for obtaining the abovementioned cellulose forms and cellulose-containing composites will also be briefly described.

It is worth noting that cellulose, its derivatives, and cellulose-containing materials are active in luminescence—they reveal so-called “own” (intrinsic) luminescence. This luminescence can suppress/mask the label function through the overlapping of luminescence characteristics of cellulose-containing material with those related to a label. At the same time, the own luminescence of the cellulose can also be used for luminescent marking/labeling (e.g., reported in [32]). So, the application of cellulose’s intrinsic luminescence for various purposes would be described in the third part (Self-labeling of luminescent cellulose materials) of this work.

Some interesting cases of luminescent materials application for labeling and visualization of cellulose-related materials are described in the final fourth part (Luminescent markers for cellulosic materials) of the paper.

Luminescent markers and labels can be used in various commercial applications such as anti-counterfeiting, bioaffinity assays, bio-imaging [33], pharmaceutical [34], food packaging [35], etc. Nowadays, agriculture, in particular farming, is increasingly transforming from traditional to precise. Precise agriculture requires continuous real-time data collection, plant condition monitoring, etc. Consequently, the elaboration of an intelligent labeling system that would allow continuous monitoring of plant condition and, at the same time, be reliable, simple, and allow digitization of sensor data is an urgent task. The light signal from a luminescent label applied to a plant can precisely satisfy these conditions [36].

At present, a large number of different markers for various applications already exist and continue to be developed. The specific type of markers is determined by the object of marking, the nature of its binding to the marker, and the possible influence of the object on the luminescent characteristics of the marker. In particular, the most commonly used luminescent markers for bio-medical applications are molecular systems with a defined structure, such as fluorescent proteins, organic dyes, metal-ligand complexes like lanthanide chelates, semiconductor, carbon, or silicon quantum dots, fluorophore-tagged latex/silica nanobeads, self-luminescent organic or lanthanide-doped inorganic nanoparticles, etc. [4, 12, 37–53].

It is worth noting that small-molecule fluorescent probes are the main instruments used for fluorescent imaging. This method has become an indispensable technique for the real-time detection and imaging in various biological systems [12]. However, there are several important drawbacks inherent to organic fluorophores that affect the sensitivity of the method. In particular, sudden decomposition of the molecule leads to photobleaching. The organic fluorophores often suffer from low signal intensities and random on/off light emission (blinking). At the same time, organic-inorganic compounds based on the metal-ligand complexes of transition metals (MC) demonstrate more attractive properties from the viewpoint of their usage as luminescent labels [54–57].

Organic dyes are among the earliest types of classical fluorescent labels used in biology. Despite their inherent drawbacks, such as small Stokes shift, poor photochemical stability, susceptibility to photobleaching, and decomposition under repeated excitation, organic dyes are still popular due to their low cost, availability, and simplicity of their application. Moreover, the new organic dyes with improved chemical stability and optical properties have been produced. It is worth noting also that intermittent on/off emission of the organic dyes is not always a drawback, but can be used as a sensitive method for the detection of single molecules. As the most commonly used dyes, the fluorescein, rhodamine, cyanine, and Alexa dyes should be mentioned [38].

Fluoresceins are used for protein labeling as this type of dye is an amine-reactive organic fluorophore. The fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC) of chemical formula C21H11NO5S is among the most popular fluorescein dyes available for this purpose. This dye is typically characterized by good solubility in water, UV and visible light absorption, high luminescence quantum yield, etc. [58]. Among the most significant drawbacks of the FITC are its sensitivity to the pH level of the solution and the photobleaching problem. The latter results in a significant decrease in the FITC luminescence intensity just after a few minutes under constant illumination [38]. Nevertheless, fluorescein dyes are widely used as tracers in analytical chemistry, forensics, and biomedical analysis [59–62]. Moreover, the close location of the excitation band maxima of FITC (λmax = 494 nm) to the emission line of argon-ion laser (λem = 488 nm) makes this dye the main fluorophore for application in flow cytometry and confocal laser-scanning microscopy [38].

Rhodamine dyes are another common type of dye that have been widely used for the labelling of biomolecules [63–65]. Rhodamine dyes with red fluorescence, e.g., 5-carboxyrhodamine 6G succinimidyl ester with molecular formula C31H29N3O7 [66], exhibit better photostability as well as emission maxima at longer wavelengths than FITC mentioned above [38]. Good matching of the fluorescence excitation peak of C31H29N3O7 (λmax = 520 nm) with a spectral line of argon-ion laser (λem = 514 nm) makes this dye another important fluorophore for laser-scanning microscopy and flow cytometry [38].

Cyanine dyes have been known for a long time as fluorophores for laser applications. This large class of organic compounds can be divided into two subclasses: 1) monomethine cyanine with the asymmetric cyanines—thiazole orange (TO), oxazole yellow (YO), or a dimer of both TO and YO (TOTO, YOYO)—as the most known representatives; 2) polymethine cyanines, to which widely used cyanin 3 (Cy3) and cyanin 5 (Cy5) are belong [38]. Due to their good water solubility, high photostability, good optical and luminescence properties, particularly, relatively high quantum yield, the cyanine dyes have been considered as prospective biological labels/markers [67]. Alexa dyes can be obtained as a result of sulfonation of the abovementioned classes of dyes, namely, rhodamine, aminocoumarin, or carbocyanine ones [68, 69]. The Alexa dyes demonstrate an outstanding performance as labels in biomedical applications, compared to other dyes [68–70]. The peculiar characteristic of the Alexa dyes’ fluorescence is that their emission and excitation bands cover a wide spectral range, spreading from ultraviolet to red light. So, it is easy to match the excitation band of the dye with the emission line of an available light source. It is worth noting that the negative net charge of Alexa dyes sometimes leads to a nonspecific electrostatic interaction with positively charged cell structures [71]. In such cases, it is better to use rhodamine dyes, which are neutral, for labeling despite their worse luminescence yield compared to Alexa dyes [38].

Fluorescent protein family with green fluorescent protein (GFP), its famous member, is another class of organic compounds suitable for luminescent labeling. In contrast to other organic compounds, namely bioluminescent ones, the GFP doesn’t require external proteins, substrates, or any cofactors for emitting light after photo-excitation. It is known that light absorption and emission in GFP are related to the chromophore that is p-hydroxybenzylidene-imidazolidinone. This chromophore originates from cyclized and oxidized Ser–Tyr–Gly own sequence of the protein at positions 65–67 [72, 73]. Currently, there are seven classes of GFP fluorophores, each one with specific components in their constituent chromophores [38, 74].

GFPs have been used as tools in numerous applications, including as biological labels to track and quantify individual or multiple protein species, as probes to monitor protein–protein interactions, and as biosensors to describe biological events and signals [38]. In particular, GFP fluorescence can be modulated post-translationally by its chemical environment and protein–protein interactions [74], facilitating the in vivo detection of gene expression [75, 76]. GFPs can be fused as luminescent labels to any kind of protein by means of genetic engineering. Importantly, during such manipulation, the target protein does not alter its functions, which allows the analysis of the protein distribution, motion, and interaction with living cells [77]. However, aggregation of fluorescent proteins in the living cell may lead to cellular toxicity, so this issue should be taken into account [78]. Another problem in the application of single proteins for fluorescent labeling is related to a possible large-time blinking (turn on/off on timescale of seconds), which is a challenge for the detection of single molecules [79, 80].

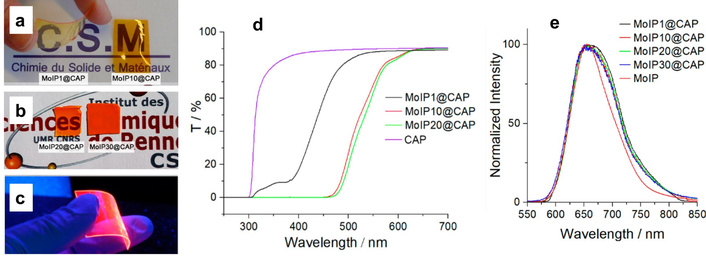

Transition metal clusters compounds of the general formula An[M6Qi8L6a] (A = alkali; M = metal atom; Qi = inner ligand, halogen or chalcogen; La = apical ligand, halogen, organic ligands) with octahedral structure belong to an actively elaborate class of luminescent additives (Figure 1). In particular, Costuas et al. [81] and Dierre et al. [82] reported that molybdenum-containing MC shows high intensity of photoluminescence (PL) in the NIR range of light. The luminescence quantum yield of MC can be from a few to nearly 100%, which depends on the types of Qi and La ligands [83, 84].

Structure of cellulose acetate phthalate (a) and the Mo6 metal nanocluster anion (b). The asterisk represents the linking point of the R group. Reprinted from [55]. © 2023 by the authors. Distributed under a CC BY 4.0.

The MC of the abovementioned type can be used in liquid crystals or various polymers as anti-counterfeiting materials [85], solar concentrators [86], wave-guiding, inkjet printing, and materials for lightning [87–90]. The MC fluorophores have been actively studied as antibacterial tools in photodynamic therapy [91, 92] and as oxygen sensors [93, 94] due to their ability to generate singlet oxygen species.

It should be emphasized that MC incorporation into an eco-friendly matrix represents a new way of designing sustainable materials. However, physical segregation of the inorganic luminescent component and organic host leads to significant light scattering. This problem should be resolved before the application of hybrid inorganic-organic composites in optoelectronic devices. Up to now, many of the studies have been performed on the properties of composites where the aforementioned fluorophores were incorporated into an organic matrix.

Luminescent lanthanide labels contain lanthanide elements of [Xe]4fn configuration with n ranging from 0 to lanthanum up to 10 for lutetium, respectively. The most important electronic transitions used for the spectroscopic properties of lanthanide complexes arise from 4f-4f intra-shell transitions. It is known that electrons of the 4f shell are shielded from the environment by the outer filled 5s2 and 5p6 shells. These outer shells also prevent a radial expansion of the 4f shell. So, the abovementioned 4f-4f transitions are weakly affected by the ligand field and chemical surroundings [95], resulting in narrow spectral emission lines is a characteristic of most of the lanthanide ions [96]. In fact, the full width at half maxima (FWHM) for Tb3+ ion luminescence bands is close to 10 nm, whereas in the case of the Alexa dye, the FWHM is about 43 nm and, additionally, a large tail at the long-wavelength side can be seen [96].

Purely electronic dipole transitions between two levels in the 4f shell are forbidden by the parity selection rule, so electronic transitions within the 4f orbitals are usually considered as the combination of electric and magnetic dipole ones. The corresponding bands are weak and characterized by low absorption coefficients [97]. However, some organic photosensitizers are able to generate the “antenna effect,” which significantly improves direct excitation of the ions [96, 98]. The excited state lifetimes for many lanthanide (rare-earth) ions, e.g., Eu3+ or Tb3+ ones, reach a few milliseconds, so there is the advantage of Ln complexes in the improved signal-to-noise ratio due to the possibility of performing time-resolved measurements. In comparison, the lifetimes for organic fluorophores are of the order of tens of nanoseconds, so time-resolved detection of the luminescence signal is impossible. Even in the case of coordination complexes containing heavy elements, like iridium or platinum, the luminescence lifetimes are only about microseconds for emission from triplet states, supported by spin-orbit coupling.

There are several important options that Ln luminescent label will possess for being suitable for bioanalytical needs. It is obvious, an absorption of the material used has to be as high as possible in an adequate spectral range. Then, the efficiency of the sensitization should be optimized experimentally for the specific lanthanide. The third, non-radiative deactivation pathways for Ln ions must be minimized, so the PL efficiency will be as high as possible. Surely, lanthanide labels should have the highest possible solubility in water to facilitate the labelling procedure. However, experimental studies have already shown that the solubility is not so critical [99–104]. Water solubility is not a prerequisite for the use of an Ln-based luminescent label, as the required result can be achieved by using a mixture of a highly polar solvent (e.g., DMSO or DMF) with water.

In a case of successful formation of Ln-based luminescent complex by attaching ligands, the next step is linking such a label to biomaterial by covalent bonding. Importantly, the biomaterial should not affect the electronic and vibrational energy levels of the label. Otherwise, the luminescent properties of the latter could be significantly worsened [96].

The metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), due to their ordered porous structure with the possibility to be adjusted for the sake of tuning chemical and physical properties, are promising materials for the elaboration of optical devices, particularly fluorescent sensors [37, 105, 106]. The MOFs are similar to the transition metal and lanthanide-based complexes. Their luminescent properties can be designed and controlled by utilizing specific molecular fragments as building blocks in order to meet the requirements of the application [107]. The physical and chemical characteristics of MOFs can be improved by moving to the ‘‘Guest@MOF’’ composite system [108], yielding luminescent materials for optoelectronic devices, e.g., optical sensors [37, 106, 109]. In such composites, the MOFs serve as a host for luminescent species, which are incorporated into the pores of the MOFs. Because of the confinement effect of the host on luminescent particles, trapped in pores, the non-radiative relaxation in the fluorophore molecule is limited, resulting in improved luminescence characteristics of the guest [110, 111]. It should also be taken into account that many of the MOFs reveal their own luminescence, forming with the guest a dual-emission system or providing an energy transfer to the guest molecule, enhancing the luminescence intensity of the latter [112].

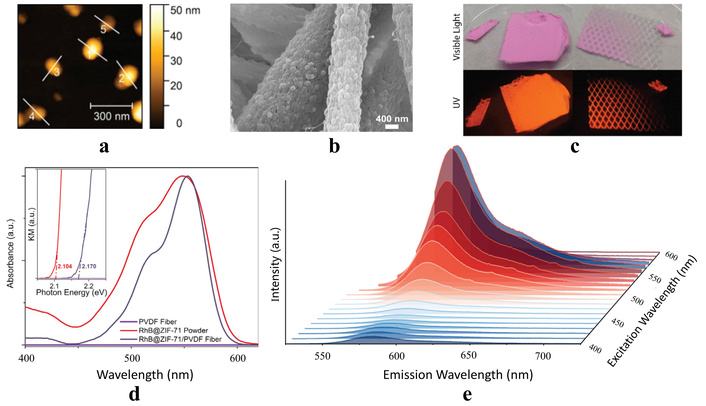

A RhB@ZIF-71 system (i.e., rhodamine B fluorophores confined in zeolitic imidazolate framework-71 host) was described in the work [37]. The system not only overcomes the drawback but also endows the material with new functions, namely, mechanochromism, thermochromism, and solvatochromism [113]. However, the Guest@MOF materials may suffer from certain shortcomings, especially poor long-term stability under real operational conditions. This drawback can be overcome by a combination of Guest@MOF material with polymer. In such a hybrid composite, the Guest@MOF material preserves its fluorescence properties, and additionally, thermal stability and processability can also be improved in this way. In particular, Zhang et al. [37] reported the preparation by electrospinning technology of the nanofibers consisting of RhB@ZIF-71 nanocrystals and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) polymer matrix (Figure 2). Such fibers are characterized by excellent thermal stability and a high quantum yield that widens the application range for this composite material compared with RhB@ZIF-71 powder [37].

Morphology and optical properties. a) AFM topography showing the nominal size of the RhB@ZIF-71 nanocrystals synthesized by the high concentration reaction (HCR) method; b) SEM image which reveal the uniform dispersion of the RhB@ZIF-71 HCR nanocrystals coated by the PVDF matrix; c) RhB@ZIF-71/PVDF fiber parts (random and textured) under the visible light and under 365 nm excitation UV lamp; d) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra (inset: Kubelka-Munk function and estimated the band gaps); e) PL map for the RhB@ZIF-71/PVDF fiber. Adapted with permission from [37]. © 2021 The Author(s). CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Today, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of quantum dots, in particular, luminescent ones, in science and technology [16, 38, 114, 115]. Several types of quantum dots can be noted that have been developed over a long period of time, and until recently. Those are carbon quantum dots (CQDs) [116, 117], perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) [118–120], and semiconductor quantum dots (SQDs) [114, 121–124]. Luminescent particles (fluorescent nanoclusters) of extra small size (< 5 nm) can also be regarded as QDs. Due to a small difference between the size of QDs and fluorescent nanoclusters (1–2 nm), these two terms correspond to almost the same objects.

It is known that the carbon quantum dots can be used as biological labels/markers as they have high solubility in water, low cytotoxicity, and good biocompatibility. In addition, they are chemically inert, and their physical properties can be adjusted by simple functionalization. However, CQDs lack sufficient quantum yield; the mechanisms of their luminescence are not clarified yet, so it is hard to find ways to improve the PL properties of the CQDs. The application of CQDs as luminescent probes requires NIR emission for two reasons: 1) Blue-green luminescence can overlap with intrinsic emission from cells and their constituents, so it is hard to separate contribution from label; 2) animal tissues are transparent in ~750–1,300 nm range, so emission in this region can be used for in vivo studies. Although most of the studied CQDs emit in the blue-green region, there are also recent reports concerning luminescence of CQDs in the yellow-red and NIR spectral regions, which is prospective for biomedical applications [47, 116].

Due to the tunable luminescence and high color purity (CP) of perovskite quantum dots, they attracted great attention as materials for photonic and optoelectronic applications, e.g., next-generation displays, topological lasers, light-emitting diodes, etc. [125]. Especially, the emerging lead halide PQDs (APbX3, where A = methylammonium MA, Cs; X = Cl, Br, I) are very exciting due to the low-cost solution synthesis process and the continuously tunable band gap by variation of halide compositions and crystal size [126, 127], comparing to traditional metal chalcogenide QDs such as CdSe, lead halide PQDs show high PL quantum yields (PLQY over 90%), narrower FWHM (12~25 nm) and wider color gamut (~150% NTSC) [127]. Details of the synthesis, treatments, functionalization, chemical, and physical properties of PQDs can be found in various reviews and original works (e.g., [118–120, 128–130]).

Semiconductor quantum dots are nanocrystals composed of chemical elements of II–VI (e.g., ZnSe, ZnS, or CdSe) or III–V groups (e.g., InP, InAs, GaAs, and GaN). The size of these nanocrystals should be up to 5 nm [131, 132]. The first studied SQDs (which were in fact semiconductor cores without any covers) revealed weak and unstable emission due to defects and imperfections of the particle surface. These defects captured the excitation energy, followed by the deactivation of the excited particle as usual, in a non-radiative manner. In addition, a high surface-to-volume ratio results in high chemical reactivity of such semiconductor particles. Consequently, some additional energy traps can be created on the basis of agents adsorbed on the surface of SQDs, leading to additional quenching of luminescence [128]. In order to resolve the noted above problem with the effect of surface on luminescence properties of SQDs, these objects were covered by a shell, resulting in core-shell structures with improved stability and quite high PLQY [38, 121].

It is worth noting that composite systems in which dyes or QDs are combined with some other nanosized labels. So-called FloDots composite systems (dye-doped silica nanoparticles) are good examples of such objects. Typical FloDots consist of luminescent organic or inorganic dye molecules dispersed inside the silica matrix. Among the advantages of FloDots, it is worth noting their high emission intensity, excellent photostability, water solubility, and efficient conjugation—all these factors make FloDots composites prospective luminescent labels [133]. Biochemically modified FloDots have been developed for various applications using well-developed immobilization protocols based on the silica surface [134–138]. Another type of composite is constructed from QDs and silica nanoparticles. These composites are the classes of luminescent materials that overcome the limitations encountered by organic fluorophores in bioassay and biological imaging applications [50].

In order to integrate the unique electrical and optical properties of carbon nanomaterials with the advantages of nanogels, the hybrid nanogels are actively being developed nowadays. As can be seen from the above, luminescent markers/labels usually have to be protected from the influence of the environment into which they are introduced, so the markers do not lose their luminescent properties. From this point of view, a marker in the form of a relatively large inorganic, in particular oxide, nanoparticle may look even more attractive than those described above, since its central part is protected from the environment by a self-formed transition layer.

A particle of an inorganic compound acting as a luminescent marker/label has to include luminescent ions of the rare-earth (lanthanides), transition, mercury-like elements [139–143], or silver [144–146]. Various types of inorganic materials, such as simple and complex oxides, fluorides, and oxofluorides, have been used as the matrices for the aforementioned ions. The multifunctionality can be considered among the main advantages of luminescent inorganic nanoparticles when used in bio-applications, as such matrices can possess luminescence sensitization. Importantly, the inorganic particles can be used simultaneously as the carrier for drugs and as an imaging probe.

Lanthanide-doped inorganic nanoparticles are characterized by narrow PL bands (lines) caused by radiative transitions in the rare-earth ions, similarly to that observed for lanthanide chelates. However, in contrast to the last ones, the rare-earth-doped inorganic nanoparticles are characterized by high photochemical stability and luminescence with a large lifetime constant (up to several milliseconds and even seconds) [38, 139–143].

A lot of papers have been devoted to elaboration of dispersed colloids of doped with Ln3+ and Ln2+ ions nanoparticles of aluminates [36], titanates [147], tungstates [148], vanadates [149], fluorides [150, 151], phosphates [152–154], fluoro-phosphates [155, 156], and silica [157]. The use of core-shell composites, where the core is doped with luminescent ions, increases the efficiency of using such nanoparticles as markers/labels. Such markers were developed and reported, in particular, in the works [158–160]. These materials have strong fluorescence, low toxicity, and are readily synthesized in water, which greatly simplifies their biofunctionalization. So, they can be regarded as promising candidates for luminescent marking and labeling. Moreover, their applications for biological purposes have already been reported [161–164].

Up-converting nanophosphors are very attractive for the purposes of luminescent labeling of bio-objects [165, 166]. A low level of own luminescence of materials under study under IR excitation, and a large spectral distance between excitation and luminescent radiation spectral bands are among the main advantages of these phosphors [167, 168].

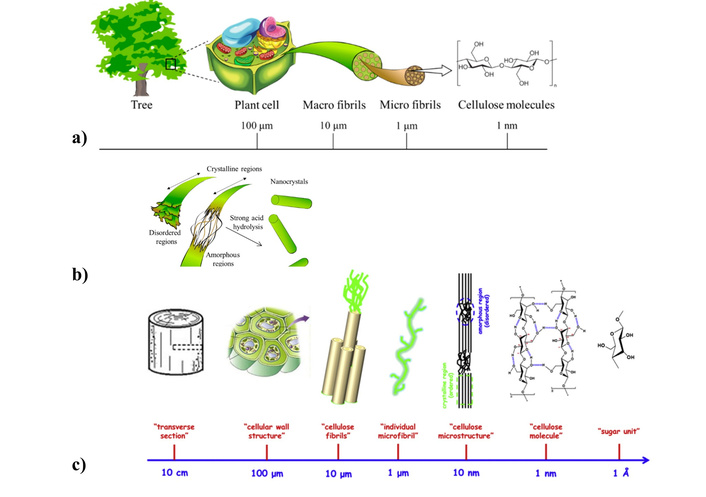

Cellulose is a natural polymer, a linear homopolysaccharide, that consists of β-d-glucopyranose long chains that are joined by β(1→4) glycosidic bonds. The chains of cellulose have glucose as a repeat unit (i.e., monomer) with a non-reducing and a reducing end [169–173]. In our opinion, Figure 3 perfectly illustrates the origin and hierarchy of the structure of cellulose forms at various levels—from the plant (tree) to the molecule.

Origin of cellulose micro/nanomaterials. Schemes of hierarchical genesis of the cellulose (a, c); scheme of cellulose production by acid hydrolysis (b). (a) and (b) adapted from [174]. © 2020 by the authors. Distributed under a CC-BY 4.0. (c) adapted with permission from [175]. © 2014 Published by Elsevier Ltd. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Considerable attention has been paid for the last few decades to studies of cellulose and its derivatives as prospective materials for modern optoelectronic devices [22]. This natural polymer has numerous advantages compared to artificial ones. In particular, cellulose-based materials are inexpensive, versatile, biodegradable, and eco-friendly systems [21]. Cellulose is one of the polysaccharides that covers a broad range of life and is the most abundant natural material on our planet, as it is the main component of the cell walls of all plants. Consequently, cellulose materials, in particular cellulose nanomaterials (CNMs), can be obtained from various abundant sources, e.g., agricultural waste, or produced by bacterial processes [170–173].

As has been emphasized earlier [31], the nomenclature of the cellulose particles has not been standardized yet. Thus, there is some inconsistency in terms that correspond to different kinds of cellulose nanoparticles in the literature. CNMs can be divided into several forms. In particular, cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) have been extensively studied over the past three decades [24, 176–180]. CNFs are usually produced through the mechanical and/or chemical/enzymatic breakdown of plant matter, using processes such as grinding, homogenization, and microfluidization. The so-called BC, produced by bacteria, also consists of similar CNFs [181–184]. It is also important to mention the microcrystalline form of cellulose—MCC [185, 186].

The CNCs are nano-sized chains with a length of about 100–400 nm and with a diameter in the 3–50 nm range. The CNFs have nano-sized chains with a length of 500–2,000 nm and a diameter in the 6–80 nm range. Both CNCs and CNFs are produced from cellulosic fibers with a crystallinity degree varying in a range of 40–90%, depending on the source of raw cellulose [187–190].

The MCC is a material obtained by purification and partial depolymerization of cellulose, in particular, by treatment of α-cellulose with mineral acids, such as H2SO4 or HCl [187, 191]. The degree of crystallinity of MCC in most cases is about 54–65%. The typical length of MCC fibers substantially exceeds that of CHFs and can be up to hundreds of microns (e.g., ~250 μm). Meanwhile, the crystallites in MCC have a length of about 35 nm, and the width was found to be approximately 3–5 nm [192]. It is seen that both MCC and NC consist of cellulose fibrils of similar dimensions. Thus, some common peculiarities in the physical properties of MCC and CNCs can be expected [187, 191, 193–195].

Taking into account the purpose of this review, it is worth mentioning a hydrogel state, as this form of cellulose material is very important regarding possible bio-medical applications of CNMs [196–199].

While glucose and cellobiose (a disaccharide consisting of two glucose molecules)—building blocks of cellulose—are easily soluble in water, cellulose itself is extremely stable against a number of different solvents, including water. The strong hydrogen bonding within the crystalline regions has been considered as a main factor in determining the insolubility of cellulose. However, this point of view is not unambiguous. In fact, amorphous cellulose is also insoluble in water, although the hydrogen bonds here are much weaker than in the crystalline part. At the same time, cellulose and its derivatives swell and can be dispersed in water, forming suspensions. The interaction of cellulose molecules with water results in the formation of numerous hydroxyl groups along the chains. These interactions have been used as a processing and activation step in the dissolution in other solvents, and the medium provides the means for the dispersion of CNMs when a cellulose-based composite is produced. The peculiarities of the cellulose-water interaction are also important from the point of view of luminescent labeling, because they determine the behavior of cellulose in relation to water-soluble markers.

Numerous examples of elaboration of the cellulose-based composite materials that were proposed for plenty of different applications can be found in the literature [200–203]. Particularly, biocomposites are among the most important. A common bio-composite consists of a matrix (e.g., resin) and plant fibers used as reinforcing agents. The artificial fibers can also be used as a reinforcing material in biocomposites, as obtaining of suitable herbal fibers may be accompanied by environmental issues and a high cost of their production. Polymer matrices can be either from renewable or non-renewable sources. The main role of the matrix in such composites is the protection of the fibers from mechanical damage and from the influence of environmental factors. Due to the advantages, such as biodegradability, relatively cheap price of production, and ease in recycling, the biocomposites are gaining increased interest as materials for flexible electronics, motors, packages, textiles, water treatment, etc. [35, 143, 204–207].

Bio-medicine is one of the important fields of cellulose-based composites applications. Cellulose can be considered a material with high biocompatibility and, as a rule, causes only a moderate response of the immune system in vivo. The low level of biodegradation of cellulose-based biocomposites is inevitably caused by a lack of cellulolytic enzymes (cellulases) in the animal or human organism. So, in general, cellulose can be considered as a material with slow (if any) biodegradability in vivo. The crystallinity, swelling, and hydration of cellulose may affect the degradation rate, absorption, and response of the immune system [175]. It is known that the best biocompatibility is achieved in the case of BC due to its biosynthetic nature. This feature is very important in the case when tissue regeneration is required (e.g., artificial bone grafts), but for some other applications (e.g., artificial heart valves or menisci), biocompatible and non-biodegradable composites can be used [22]. Biomaterials, based on nanocellulose, can be used as special tissue bio-scaffolds, which provide advantageous conditions for cell attachment and proliferation. Such materials are characterized by high biocompatibility and reveal mechanical properties close to those of natural tissues [22]. Up to now, there are many nanocellulose-based biomaterials have been studied, namely composites, hydrogels, nanofibers, membranes, etc. As mentioned above, BC is a very interesting medium for cell culture due to its low cytotoxicity and high porosity [175, 207]. The details about the advantages and drawbacks of the various cellulose derivative materials and cellulose-based composites can be found in the aforementioned and some other original and review papers (see, e.g., [208–216]).

On the whole, there is also no evidence for serious influence or damage caused by nanocellulose on both cellular and genetic levels, as well as in vivo organ and animal experiments. However, further systematic studies on the possible negative effects of nanocellulose on living organisms, particularly through the agglomeration of particles in the body, are of high importance. Nevertheless, high chemical and photochemical stability, hydrogen bonding capability, and low cytotoxicity of various types of cellulose-based materials/derivatives have determined their current and potential usage in pharmaceutical applications [34, 217, 218]. These materials are components of many medicines; in particular, the cellulose ethers and esters are part of more than 10 types of drugs of various actions, in particular, Desogan, Flumadine, Flurbiprofen, Lopressor, Oxycontin, etc. [217].

Cellulose derivatives are widely used for thickening of suspensions and emulsions, in particular, those that are pharmaceutical solutions [217, 219]. These materials can also increase the viscosity of non-aqueous dispersed systems, like organic-based ones. Viscosity enhancement of drug solutions poses many advantages, such as improving consumption controllability and increasing the residence time of drugs in topical and mucosal solutions, which leads to improved bioavailability of topical, nasal, or ocular preparations. It has been revealed that viscosity enhancement, in some cases, can increase the absorption of some poorly absorbing drugs like insulin from oral dosage forms [220]. In the case of emulsions of drugs, utilizing cellulose derivatives improves resistance against mechanical and thermal shocks, increasing their shelf life. Currently, cellulose ethers of high molecular weight have been considered as the most suitable additives for increasing of viscosity of pharmaceutical solutions [220].

The other way to improve the specific localization of drug delivery to various biological objects and increase their residence time is bio-adhesives and muco-adhesives. Such systems were proposed about four decades ago and are widely used nowadays [221, 222]. Bio- and muco-adhesives are formulated to use on the skin and mucus membranes of gastrointestinal, ear, nose, eye, rectum and vagina. Smaller size and thickness, compared to tablets, of such dosage forms result in better patient compliance. Both bio- and muco-adhesives have usually been prepared in the form of polymer films, incorporated with drugs. After combining with moisture or mucus substances, these films should adhere to biological membranes, with subsequent release of the drugs. Depending on the release rate in such drag delivery systems, it is possible to change the residence time of the medicines and adjust dosing frequency [221, 222]. So, specific requirements should be met by film-formers and adhesive polymers. The bio-adhesive compositions were elaborated on the basis of synthetic (e.g., acrylic derivatives: polycarbophil and carbopol), natural (acacia, alginates, carrageenan or pectin), or semi-natural (chitosan and cellulose derivatives) polymers. Among the latter ones, the cellulose ethers are known components of bio-adhesives. They are used in various types of drug-in-polymers films, in particular, suitable for buccal, ocular, vaginal, nasal and transdermal treatment, both alone or with combination of other polymers. More recently used cellulose ethers in bio-adhesives include nonionic cellulose ethers such as ethyl cellulose, hydroxy ethyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), methyl cellulose, carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) or hydroxylpropylmethyl cellulose (HPMC) and anionic ether derivatives like sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (NaCMC) [223, 224]. In contrast to polyacrylate and thiolated-based polymer films, the cellulose ethers, such as NaCMC and HPC, have little dependency of adhesion time and adhesion force on the pH of the medium. The adhesion properties of cellulose derivatives can be improved by the use of additional polymers or polysaccharides.

Both cellulose ethers and esters are widely used as functional covers for solid dosage forms of medicines, e.g., pills, tablets, microcapsules, etc. These covers protect drugs against humidity and oxygen, and prevent the enzymatic and acidic degradation. In addition, the smell and taste of such medicines can also be masked. Among the advantages of using covers for solid drug forms is the possibility of controlling release in such dosage forms (e.g., delayed, extended, step-by-step release, etc.).

Another important type of medicine is based on gel-like substances incorporated in a polymer shell. It is known that gels can be formed by soluble and insoluble cellulose ethers through the absorption of water [225, 226]. Among them, HPMC and CMC, derivatives of cellulose widely used as gelling agents in drug compositions. In contrast to natural gelling agents, like sodium alginate, agar, pectin, and gelatin, the HPMC and CMC are less sensitive to microbial pollution [197, 227].

Currently, the prevailing part of commercial packaging of food and goods is related to the use of petroleum-based materials, which results in negative effects on the environment. Due to its abundance, biocompatibility, low (if any) level of toxicity, and ease of disposal in an eco-friendly way, cellulose-based materials are considered an outstanding alternative for commercial packaging films. Among the main drawbacks of cellulose films for food packaging are their low antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Consequently, pure cellulose-based films do not succeed in food preservation performance. Last time, packaging films were intensively developed by incorporating antioxidants and antimicrobial agents such as natural extracts, natural polyphenols, nanoparticles, and microparticles into the cellulose-based films [35, 67, 202, 227, 228]. The changes in the other properties of the films, such as hydrophilicity, water evaporation rate, and mechanical properties, have to be monitored if noted additives are incorporated. One can see that the impact can be reflected in luminescent characteristics of both the cellulose matrix and additives.

Agriculture is another important field where luminescent labeling can be used as a very effective tool. The most challenging tasks in modern smart agriculture are the precise labeling and recording/reading of information about the peculiarities of the growth of the plants [229]. The Agricultural Internet of Things (IoT) concept requires the evolution of traditional agriculture into a precision one, through a significant shift in farming practices [36]. Comprehensive monitoring of various indicators of plant life is the key point for the creation of smart farms [230]. Thus, precision agriculture requires real-time monitoring, large data collection and processing abilities, accompanied by intelligent decision support in order to improve farming efficiency by variation of plant growth conditions. Consequently, the development of an intelligent plant labeling system with high reliability, simple record/read/update functions, and easy integration with available IoT platforms is of high importance for modern agriculture [36, 52, 230–234].

Cellulose materials, particularly nanocellulose, have been extensively investigated as excellent biomaterials in membrane filtration due to their exceptional properties, such as large specific surface area, anti-fouling behaviour, high aspect ratio, etc. The large surface area of nanocellulose contains a large number of free hydroxyl groups, which are easily modified and functionalized. It was shown that the modified nanocellulose can be used in filter membranes to improve their abilities in removing heavy metals, oil, or organic compounds from water solutions/suspensions [196, 235–237]. It is known that some of the noted compounds, which should be removed, are active in luminescence, so their PL characteristics can be used for labeling purposes and control of the removal process [238, 239].

It is obvious that for each type of composite and its application, the type and method of using luminescent markers/labels may or must not be the same. This fact should always be taken into account when planning studies with luminescent labeling of cellulose materials [23, 29, 36, 171, 238–240].

Cellulose in its various forms, cellulose derivatives, and cellulose-containing materials are able to reveal visible luminescence. The intensity, spectral profiles, band positions, and luminescence decay kinetics depend on various factors (e.g., origin of cellulose source, parameters of the environment, like temperature and humidity, etc.). Own/intrinsic luminescence of the cellulose is, typically, less intense compared to light emission by common luminescent agents, like ions of the rare-earth and transition elements or quantum dots. However, available scientific data indicate the possibility of using characteristics of cellulose’s own luminescence for tracking the response of cellulose-containing materials to external impacts. Such a response allows considering of own luminescence of cellulosic materials as their self-marking/labeling [241, 242].

So, it is reasonable to point out some characteristics of cellulose’s own (or intrinsic) luminescence. It is generally accepted that own luminescence in the case of solids occurs without special incorporation of any additive luminescence agents, but it can be related to constituents of the lattice or intrinsic defects of the material. The PL of various cellulose-containing materials has been studied and reported for a while [241–246]. The intensity of this luminescence is quite high, so it can be easily observed at appropriate PL excitations.

Luminescent characteristics of two types of microfibrillar, one type of nanofibrillar celluloses, and birch cellulose have been described in detail in the literature [247]. The PL spectra were measured with a time delay between the excitation pulse and the start of the detection. Such an experimental design allowed distinguishing the PL spectra of fast and slow components of the cellulose emission.

Four types of cellulose forms (MCC, MFC, NC, and BC) have been mainly used for the luminescent study in the works [27, 30, 248, 249]. The main characteristics of the MCC, MFC, NC, and BC luminescence are similar to each other and are typical of those for cellulose-based materials measured elsewhere. Three PL bands with maxima near 370, 430–470, and 505–510 nm can be distinguished, and they have been ascribed earlier to three different luminescence centers [250]. The PL bands with maxima near 420–460 and 495 nm were also reported in the literature [251, 252]. The statements above concern the luminescence of the cellulose materials made from different sources such as bleached craft and sulfite pulps, Whatman filter paper, biomedical cellulose, etc. [252, 253].

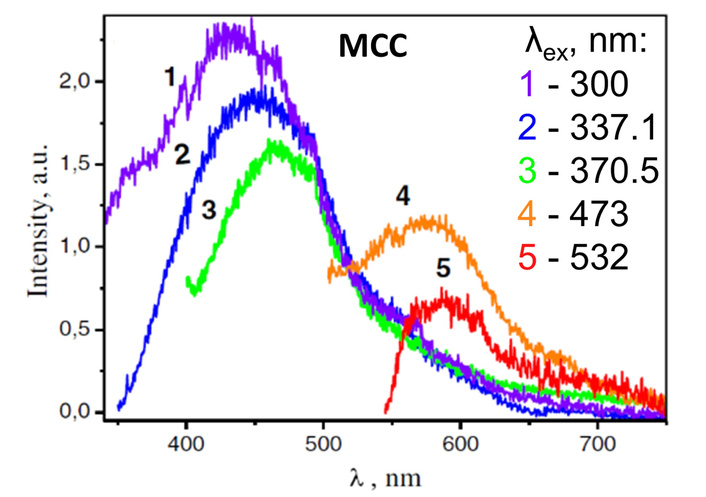

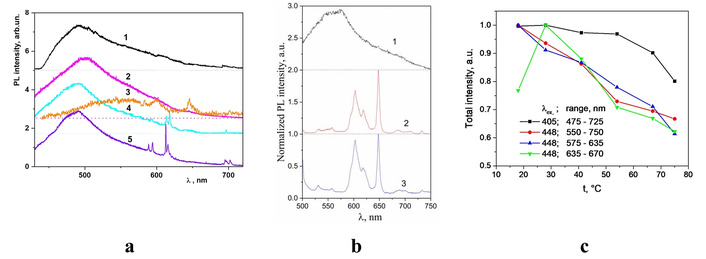

It is known that the preparation and treatment conditions have a significant effect on the crystallinity and structure of cellulose-based materials, resulting in differences in physical properties, namely spectroscopic ones. In particular, the wide complex PL band in the 325–750 nm spectral range was reported for the MCC samples when the excitation wavelength varies from λex = 300 to 532 nm [30, 248]. The peak position, band shape, and peak intensity of the PL band depend on the excitation wavelength, λex. The peak position, λmax, shows a tendency to shift to the long-wavelength side with increasing excitation wavelength (Figure 4). The blue emission component, located at 430–470 nm spectral range, dominates in the PL spectra measured under UV excitation. The PL excitation in the visible spectral range (λex = 450–530 nm) leads to the appearance of a yellow-red luminescence band covering the range 500–700 nm, and with maxima position approximately at 580–590 nm (Figure 4, curves 4, 5) [30].

Steady state luminescent spectra of microcrystalline cellulose samples measured at excitations with λex = 300 (1), 337.1 (2), 370.5 (3), 473 (4), and 532 nm (5). Adapted from [30]. © The Author(s) 2017. Distributed under a CC-BY 4.0.

It can be assumed from the spectroscopic studies that the cellulose-based materials should have several types of luminescence centers. In particular, the presence of several emission maxima and the multi-exponential phosphorescence decay of the PL supports the assumption above. Unfortunately, the origin of these centers is still unclear, and additional studies are required.

It can be assumed from the spectroscopic studies that the cellulose-based materials should have several types of luminescence centers. In particular, the presence of several emission maxima and the multi-exponential phosphorescence decay of the PL supports the assumption above. Unfortunately, the origin of these centers is still unclear, and additional studies are required. Regarding the electronic structure of the basic elements of cellulose composition, the β-(1,4)-glycosidic linked glucose unit, it is hard to expect that it would be able to reveal any luminescence. However, glucose and cellobiose can absorb excitation light, followed by the transfer of absorbed energy to emission centers. In particular, the UV band with λmax 265 nm in the absorption spectra of “pure” cellulose was ascribed to the glycosidic –C=O bonds in molecular groups, which occur after isolation and purification of cellulose [251]. Based on the simultaneous theoretical and experimental studies, Da Silva Perez et al. [254] suggested that interaction between cellulose-related molecular groups leads to the formation of an energy state, responsible for light absorption by cellulose. Bikova and Treimanis [255] reported that monocarboxyl cellulose in NaOH solutions and oxidized lignin-free xylan reveal the absorption bands in the 190–500 nm spectral range. It is worth noting that the spectra were recorded for cellulose in alkaline media, where dissociation and ionization of carboxyl groups can be followed by isomerization of aldo- and keto-groups. The most intensive bands in absorption spectra can be ascribed to the following chromophores: 1) in the range of 200–220 nm—carboxyl groups; 2) 230–250 nm—furan-type aromatic compounds; 3) 270–290 nm—carbonyl groups; 4) 290–320 nm—pyron-type heteroaromatics; 5) 350–370 nm and 6) 430–450 nm—conjugated heteroaromatic species through charge-transfer mechanism.

The variation of intensity and maxima positions of PL bands for cellulose materials obtained from different sources (Avicel, cotton linters, sisal cellulose, sisal holocellulose, and anhydroglucose) has been reported earlier [256]. In the abovementioned study, the chemical modification of bleached hardwood papers was performed in order to increase the carboxylic content in them. The soluble samples of polymers in dichloromethane were obtained by acetylation of the cellulose in a homogeneous lithium chloride/N, N-dimethylacetamide solution (DMAc/LiCl). It was found that the presence of carboxylic groups in the anhydro-glucose units shifts the emission maxima by 10 nm to shorter wavelengths and increases their intensity. Oxidizing decreased the cellulose PL intensity by creating carbonyl groups. This effect is common for various cellulose samples regardless of their source [257]. At the same time, no correlation was found between the maxima position of the PL band (λmax) and average molecular weight (Mvis) or crystallinity index. In particular, it was reported that maxima position shifted to shorter wavelength in the sequence cotton linters–mercerized sisal cellulose–MCC; whereas Mvis increases in a row MCC–cotton linters–mercerized sisal cellulose; and PL intensity increases in a row mercerized sisal cellulose–cotton linters–MCC [257]. Based on the result of the study, it was suggested that each anhydro-glucose unit emits light as a separate chromophore, so strong interactions between these units can be excluded [257].

The main factors that lead to quenching of cellulose emission were also discussed earlier. Bateh and Winefordner [241] studied pulps of cotton linter and wood, as well as several types of paper filters, as room-temperature phosphorescent materials. It was found comparing “the best” and “the poorest” paper that the difference in their performance is considerably lower than an order of magnitude. However, later studies revealed the quenching effect of aldehyde and ketone carbonyl groups on cellulose fluorescence [256, 258].

The luminescence centers in cellulose materials can also be connected with “external” factors, like pulp processing and treatment. They can contribute to the formation of some aromatic structures at the reducing end groups of cellulose or hemicellulose [259]. It should be emphasized here that those related to quinones [253]. Most of the chromophores are ascribed to hydroxy-acetophenones, hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinones, and hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinones. As a possible source of cellulose luminescence, the traces of the residual lignin or proteins, di-tyrosine, and coumarin acids should also be taken into account [246, 253, 257, 260, 261].

Possible contribution of transition-metal ions such as Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, and Ti remaining after normal preparation procedures to the cellulose PL was studied under excitation of emission by power laser radiation of the cotton-derived samples of cellulose [244]. However, the PL properties of the abovementioned ions are very specific (features of emission and excitation spectra, decay kinetics). Thus, the manifestation of PL of transition metal ions can be easily seen on the background of cellulose’s own PL [246, 262], if the formers are present in cellulose materials. Analyzing the available literature data concerning cellulose luminescence, it is reasonable to assume that the impact of uncontrolled impurities of transition metal ions can be neglected in most cases.

Luminescence kinetics is a very important characteristic that allows distinguishing the specific emission centers in cellulose materials. In the case of MFC, the PL kinetics curves can be fitted by four or five independent slow decay processes, which are characterized with decay constants ranging from 1.2 to 361 ms [247].

The PL decay curves differ from each other for cellulose samples from various sources, and can be fitted by a sum of several exponential decays each. It was found that PL intensity decreases by about 30 times during 10 ns. It is worth noting that the PL decay curves at the 0–30 ns region can be distorted by a significant portion of scattered light from the light-emitting diode that was used for PL excitation. In the case of luminescence registered at longer wavelengths (500–700 nm), the PL decay became slower, which indicates that the slow component is related to the long-wavelength emission components of cellulose [247].

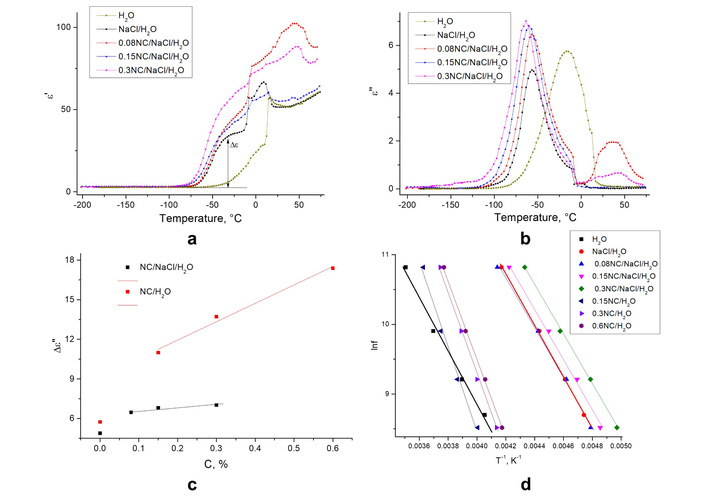

Many cellulose-based materials are elaborated from aqueous solutions. As mentioned above, the luminescent labeling is also often performed with the use of water solutions. Thus, the role of water molecules and their effect on the optical and dielectric properties of cellulose-containing materials has attracted significant attention (e.g., [263, 264]). A correlation of the luminescent properties with dielectric characteristics of the water solution of NaCl salt and nanocellulose had also been studied in our earlier work [265]. The dielectric properties were determined by recording the temperature dependences of the real ε/(T) and imaginary ε//(T) parts of the complex dielectric permittivity. The finding (Figure 5a, b) showed that relaxation processes occurred at these temperatures. A system modeled as an ensemble of identical relaxators was used to calculate the energy characteristics of the relaxation process. In this model:

Complex dielectric permittivity behavior. Temperature dependence of the real (a) and imaginary parts (b) of the complex dielectric permittivity for H2O, NaCl/H2O, 0.08NC/NaCl/H2O, 0.15NC/NaCl/H2O, 0.3NC/NaCl/H2O; (c) height of the ε// peak (relaxation process maximum) vs. NC concentration in NC/H2O and NC/NaCl/H2O solutions; (d) Arrhenius plots, [ln(f) vs (1/T)], for NC/H2O and NC/NaCl/H2O samples, frequency of the external field is 10 kHz. Adapted with permission from [265]. © 2023 The Author(s).

Each of relaxators is described with two non-equivalent energy states, marked as 1 and 2, separated by some potential barrier [265];

the real and the imaginary components of the dielectric permittivity obey the following equations [62]:

where τ is a relaxation time, which can be estimated as:

The relaxation time τ is in relation to such energy characteristics of the dielectric relaxation as activation energy—U; and entropy of activation—ΔS:

where τ0 = 10–12 s; U—activation energy; ΔS—entropy of activation; k—Boltzmann’s constant [265].

It is easy to see that the increment of the dielectric permittivity is described by Equation 5:

N value is a concentration of relaxators in the formulas above, μ2—mean square of the difference of the relaxator dipole moments in states 1 and 2, V—the energy distance between 1 and 2 states. If to fit the ε/(T) experimental dependences in Figure 5a with Equation 5, the values of

It is obvious that the maximum on the ε//(T) dependency occurs when ωτ = 1, where ω = 2πf is the angular frequency of the external field. As a result, the next equation can be written:

Thus, ΔS and U dielectric relaxation parameters were evaluated with the use of so-called lnf (1/T) Arrhenius plots [265] (Figure 5c, d).

So, it was concluded that increasing the nanocellulose content in the suspension leads to a shift of the dielectric relaxation processes toward lower temperatures [265]. Interestingly, activation energy increases when nanocellulose is added to water, but the effect disappears when NaCl is introduced into the solution. The binding of water molecules with sodium ions was assumed to be the main factor causing a decrease in the intensity of the dielectric relaxation in the ions–water–cellulose solid solutions compared to water–cellulose ones. In fact, the binding of water molecules prevents the formation of hydrogen bonds between the molecules of water and methylol groups. As a result, the conformational motion of surface methylol groups is blocked, and the corresponding band of dielectric relaxation decreases in intensity [265].

The luminescence spectra of the nanocellulose suspensions described above are similar to those reported earlier for various cellulose forms (Figure 6).

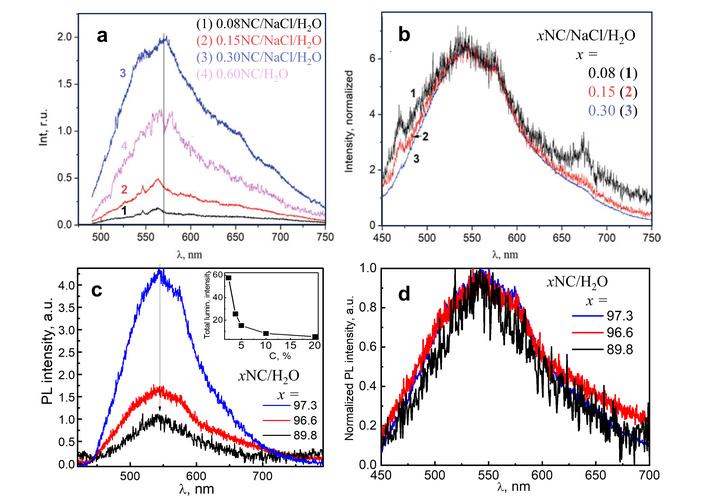

Luminescence spectra of the xNC/NaCl/H2O system. (a) The PL spectra of xNC/NaCl/H2O (1–3), and 0.6NC/H2O (4) solid solutions, λex = 473 nm; (b) normalized PL spectra from (a); (с) PL spectra of xNC/H2O samples (inset: dependence of the total PL intensity on water content); (d) normalized PL spectra from (с), λex = 405 nm, T = 290 K. (a) and (b) adapted with permission from [265]. © 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG. (c) and (d) adapted with permission from [266]. © 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

The PL of these samples is relatively weak, as water molecules surround the cellulose fibrils and, consequently, affect chromophore (fluorophore) molecules on their surface. Increasing the nanocellulose content in suspension leads to an increase in PL intensity because the content of fluorophore molecules also increases (Figure 6). It was mentioned that when dielectric properties were discussed, the sodium ions bind to water molecules, preventing access of the latter to cellulose-related molecules. As a result, the quenching of the PL by water molecules becomes less significant. So, it can be assumed that Na cations play the main role in promoting of the cellulose-related luminescence in water–cellulose–NaCl solutions (curves 3 and 4 in Figure 6a). The results obtained by luminescence spectroscopy are in accordance with dielectric studies, as they both support the assumption that the ions of NaCl salt prevent the formation of the hydration shell around the cellulose molecules [265].

As the results of using nanocellulose are determined by moisture content, it was not surprising that the impact of moisture content on the physical properties of nanocellulose has drawn significant attention [263–268]. The NC obtained by hydrolysis of the cellulose prepared by organosolv of Miscanthus x giganteus stems [268] has been used for the preparation of the set of samples [266]. The NC films with a moisture content of 10.2% (marked as 89.8 NC/H2O), 3.4% (96.6 NC/H2O), and 2.7% (97.3 NC/H2O) were prepared and studied.

These “hydrated” nanocellulose films reveal a wide complex PL band (Figure 6c and 6d), similar to that described above for solutions as well as for solid cellulose samples. The significant decrease of PL intensity was found with the increase of water content (Figure 6c and inset). The shape of this PL band also changes with variation of the water content (Figure 6d) [266].

Since the high-frequency vibrations ( ~1,800 and 3,600 cm–1) are inherent to water molecules, they are known as effective quenchers of the luminescence in various solid-state samples. In other words, the energy of the excited state of the fluorophore, in the presence of H2O molecules, may dissipate as phonons in a non-radiative way [269, 270]. The results presented in the inset in Figure 6c confirm the above-mentioned statement as the PL intensity of the nanocellulose abruptly decreases with the increase of water content from zero to 10.2 %. So, it is likely that at such water content, the number of H2O molecules is enough to interact with the prevailing part of the cellulose-related chromophores. To test this assumption, the PL experiments were performed with NC films in a weak stream of water vapor for 1 (point marked as 5%), 6 (10%), and 15 minutes (20%). It was found that with the further increase in the amount of moisture, the luminescence intensity decreases more slowly (inset in Figure 6c). This is also a change in the shape of the PL band with variation of water content (Figure 6d). So, different chromophores/fluorophores, probably, react with water molecules in different ways and, as a result, the quenching rate of their PL is not the same.

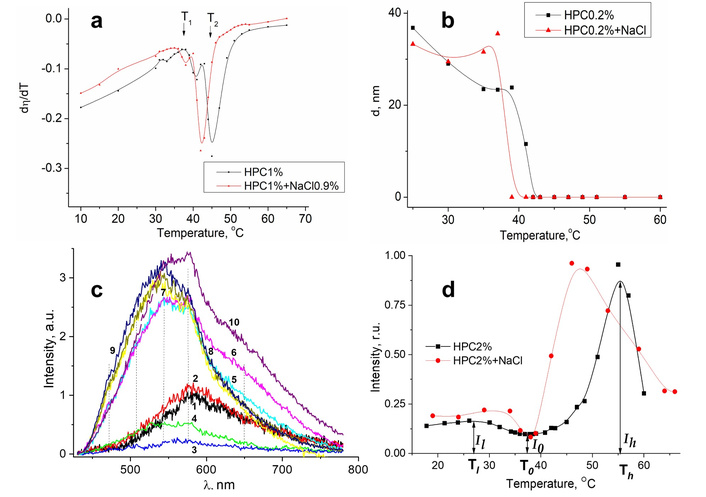

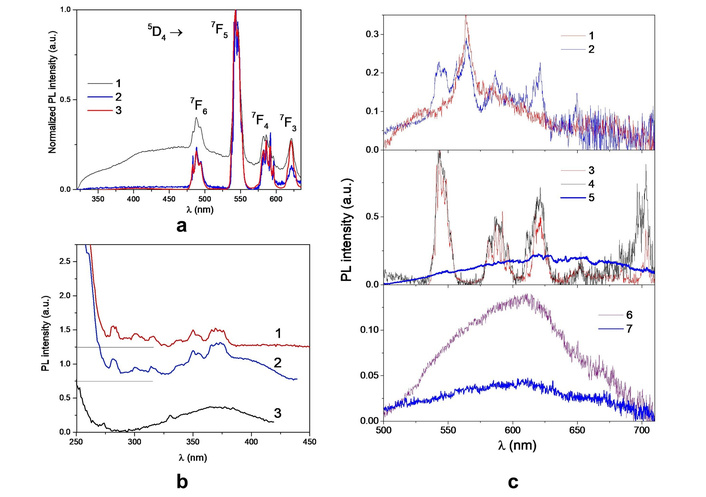

Luminescent cellulose self-labeling allowed studying the influence of alkali metal ions on some cellulose derivatives. The impact of the alkali metal ions on the HPC water solutions was discussed in our recent papers [271, 272]. Our interest in such a study was caused by the fact that the HPC is known to undergo a structural phase transformation with a so-called Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST). This structural transformation in aqueous solutions of HPC has been known for a while [273]. It is also known that when their physical properties, e.g., rheological and optical ones, are changed significantly in the narrow temperature range near the LCST. At the same time, the effects of the external factors on the characteristics of the phase transitions have been intensively studied up to now [274–276]. The interest in such studies is connected with technological problems of “smart materials”, whose physical and chemical properties are a function of external parameters (temperature, pressure, pH, electric and magnetic fields, etс.). Various characteristics of the HPC solutions containing Na+ and Cl– ions were studied in the temperature range 10–70°C, as the LCST point can be located near 40–45°C [272]. In fact, two points of singularity were found for the HPC:Na+,Cl– solutions (concentration of HPC was 1%, and NaCl salt in solution is 0.154 mol/L) in the noted temperature range (Figure 7).

Effect of temperature on dynamic viscosity and luminescence characteristics. Temperature dependences of the change of the dynamic viscosity rate (a) and nanoparticles sizes (b); (c) the PL spectra of the NaCl-HPC solutions at different temperatures: T = 19°C (1), 34°C (2), 38°C (3), 39°C (4), 42°C (5), 46°C (6), 53°C (7), 59°C (8), 64°C (9), and 64°C (10); (d) the dependences of the PL intensity on temperature. HPC concentration is 2%; concentration of NaCl salt is 0.154 mol/L. (a) and (b) adapted with permission from [271]. © 2022, IEEE. (c) and (d) adapted with permission from [272]. © 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

The PL spectra of HPC suspensions both with and without NaCl were obtained at certain temperatures within the noted temperature range (Figure 7c). The dependencies of the PL intensity on temperature for HPC solutions are shown in Figure 7d. It can be seen that the shape of the bands in the PL spectra changes at the LCST point, where phase transition takes place. The changes in the PL spectra with further increasing temperature are not significant. It should be emphasized that two maxima are observed in the PL intensity dependencies shown in Figure 7d. There are two subregions that can be distinguished in the low-temperature region for HPC-NaCl systems (Figure 7d, red curve): A plateau from 17°C to about 25°C, and a subregion with a maximum near 32°C. The latter region corresponds to the active formation of large particles after adding the sodium chloride to the suspension.

The observed changes in the PL properties can be ascribed to the destruction by Na+ ions of the hydrate shell of water/HPC chains, with further formation of the hydrate-solvation shell. The effect of the latter on the luminescent properties of the luminescent centers is not identical to the effect of a hydrate shell. The temperature behavior of the spectra and luminescence intensity of HPC–water–MCl (M = Li, K, Rb, and Cs) systems was found to be similar to that of NaCl-HPC. The extrema positions (T1, T0, and Th in Figure 7d) and the PL intensities at corresponding temperatures (I1, I0, and Ih in Figure 7d) have different values for the systems containing different salts. Since the mechanisms affecting the PL spectrum in low- and high-temperature ranges are different, it is convenient to use a quantity Rlum, which takes into account the luminescent characteristics of the solutions in these temperature regions and can be calculated by Equation 7:

where Il, I0, and Ih are the PL intensities at temperatures T1, T0, and Th, as was outlined above. The values of temperatures Tl, T0, and Th, as well as the Rlum values, are noted in Table 1.

Temperature points and Rlum values for the HPC–water–MCl systems.

| Temperature and Rlum | Solution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPC | HPC-LiCl | HPC-NaCl | HPC-KCl | HPC-RbCl | HPC-CsCl | |

| T1, °C | 27.1 | 25.9 | 31.7 | 24.8 | 27.0 | 30.2 |

| To, °C | 37.3 | 38.2 | 38.1 | 35.8 | 41.3 | 41.2 |

| Th, °C | 55.1 | 52.3 | 46.2 | 43.5 | 43.4 | 46.0 |

| Rlum | 12.8 | 3.91 | 6.32 | 4.03 | 2.26 | 4.14 |

M = Li, K, Rb, and Cs. Adapted with permission from [272]. © 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

The data in Table 1 show that the T1 and T0 values reveal no trends or regularities in the studied homologous series of the salts. This can be expected, as various processes are involved at low temperatures. Thus, it is currently impossible to untangle the impact of each actual mechanism [272].

The value of T0 then plays a technical role: to determine the value of I0. In contrast, both of the Th and Rlum values consistently decrease for solutions with cations Li+→Na+→K+→Rb+. Clearly, this trend is due to the ionic mechanism of alkali metal ions’ impact on the structure of water in the nearest surrounding of the HPC molecules/chains [272].

It is worth mentioning that spectral profiles and intensity of the intrinsic luminescence of the HPC–water–salt suspensions are quite sensitive to the changes in the structure of the water in these solutions, which allows monitoring the thermal behavior of sol–gel phase transition in the noted systems. Through such luminescence analysis, a self-association of HPC particles with quite a large size (above 2 microns) was confirmed. The presence of alkali metal ions in the HPC solution decreases the LCST and leads to the appearance of large nanoparticles at temperatures above the LCST. Interestingly, this temperature decreases from about 55° to 43°C along the Li+→Na+→K+→Rb+ homological row [272]. The described luminescent studies confirm the importance and perspectives of the luminescent self-marking of cellulose and its derivatives.

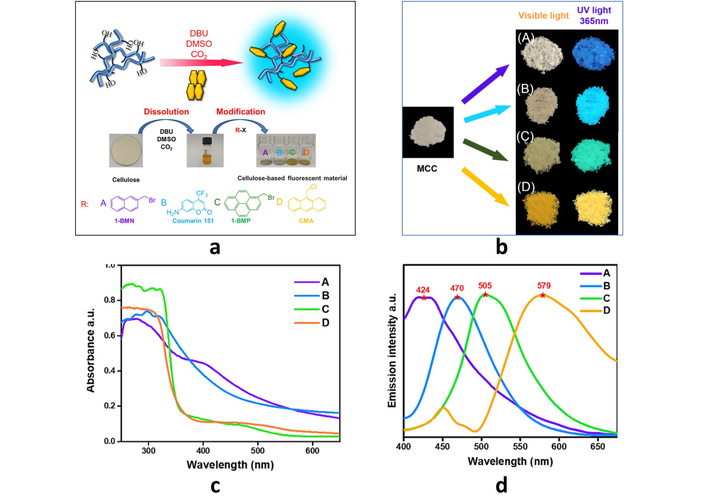

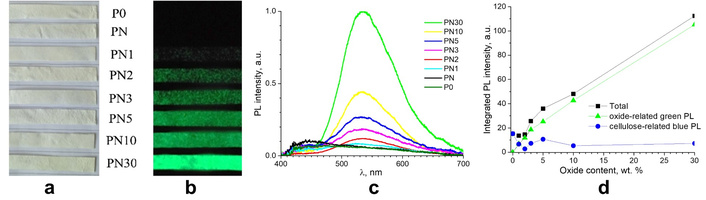

Cellulose materials incorporated with fluorescent dyes can combine perfectly the multi-functionality of the organic dyes with well-known mechanical and optical properties of the cellulose and its derivatives [277–281]. The cellulose-based samples can be obtained by various methods, like cross-linking, co-polymerization, or self-assembly.

In particular, Yao et al. [282] reported the results of the preparation and studies of a series of cellulose-based fluorescent aggregations encapsulated with FITC with different morphologies. The maximum fluorescence intensity was observed in the case of flower-like fluorescent aggregates. Such a result was ascribed to the matching of several factors, including the hydrogen bonding, electrostatic repulsion, rigid structure of cellulose, and the larger surface area in flower-like aggregation as a result of inhibiting π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding interaction of FITC. So, cellulose-based fluorescent aggregation could be processed into fluorescent fiber, coating, and printing patterns, and it has potential applications in information storage, scene warning, and special fiber [282].

Although various types of dyes have been introduced into cellulose, few works have been devoted to studying specific mechanisms of the interactions between the dyes and the cellulose materials, as well as specific behavior (e.g., aggregation, etc.) of the marker in cellulose host. However, such interactions and self-assembling could have a significant effect on the PL intensity, spectral, and kinetic characteristics of luminescent label [283, 284].

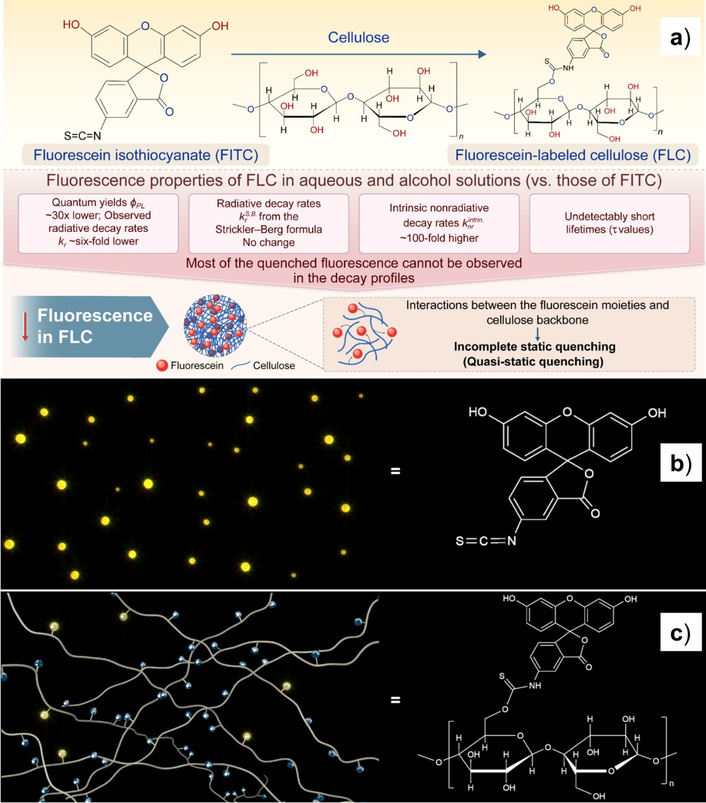

Yen et al. [58] studied the issue when the cellulose matrix quenches the PL of the dye, in a dynamical or statistical way (Figure 8a). It was suggested that the local (microenvironmental) rigidity of cellulose may be increased by linking a dye molecule to the polymer chain (Figure 8b, c). This potentially leads to a decreased rate of nonradiative relaxations and thus the quantum yield of the fluorescein increases [285–288], but the opposite can also be observed [58].

Cellulose with Fluorescein molecules. Graphical depiction of the study performed, including the chemical structures of the materials being compared and a summary of the results (a) and the PL behavior without (b) and with a cellulose network (c). The PL intensity FITC is higher and consistent (yellow dots), while the main part of the fluorescein moieties is quenched (dark blue spots) as attached to the cellulose molecules. Adapted from [58]. © 2024, The Author(s). Distributed under a CC-BY 4.0.

Despite the high popularity of the fluorescein dyes, they have typically been used with unsustainable substrates. At the same time, interactions of cellulose as a sustainable medium with fluorescein require additional studies. Although the fluorescence of a fluorescein derivative was reportedly enhanced on the cellulose backbone [289], some luminescence characteristics of the fluorescein/cellulose composites are known, but some others are poorly studied. Particularly, the luminescent properties of FITC and fluorescein-labeled cellulose (FLC), including their PL quantum yields, lifetimes τ, and rates of radiative kr and nonradiative knr decay, were determined earlier in solutions, namely water and alcohol [58]. It should be noted also that spectral profiles of emission don’t differ significantly for all the samples, when PL decay kinetics and PL efficiency vary significantly.

The dissolved FLC had about 30 times lower PLQY than FITC, six-fold lower kr, but a 10–20 times higher knr with respect to their FITC counterparts. It was suggested that the incorporation of FITC into the cellulose chains remarkably reduces its fluorescence efficiency. Presumably, this was because the cellulose backbone interacted weakly with the fluorescein moieties, suggesting a quenching mechanism that can be termed quasi-static, corresponding to static quenching between the fluorescein moieties and cellulose backbone, in addition to the fluorescence quenching caused by the intramolecular nonradiative processes of fluorescein, as observed in conventional molecules [58]. The schemes of the process above are illustrated in Figure 8b and 8c.

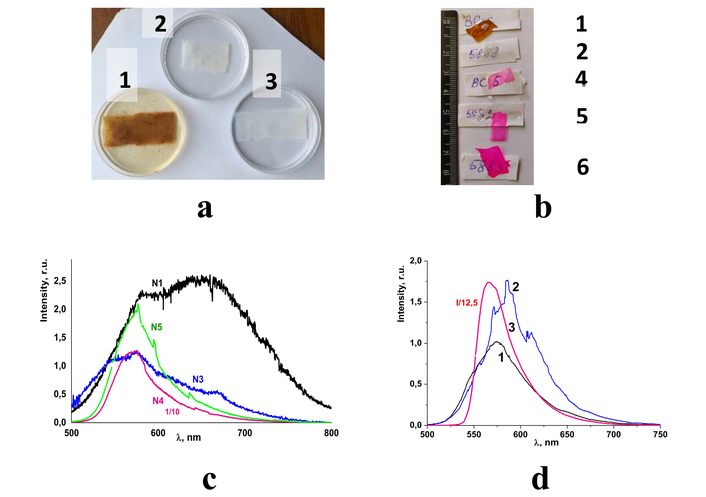

The results of the studies of bacterial nanocellulose samples that were obtained by the Kombucha membranes method [290, 291], incorporated with Rhodamine C, have been reported earlier [63, 292]. The concentration of dye (filler) was changed by variation of the soaking time of previously prepared BC films in a solution of Rhodamine C in alcohol (dye concentration was 10–4 mol/L).

Figure 9a and 9b show the unbleached BC film (1), the BC film bleached in 1% aqueous solution of NaOH during 24 h (denoted as BC2), sample bleached in NaOH solution during 192 h (BC3), and samples soaked in Rhodamine C during 5, 30 and 300 seconds (denoted as BC4, BC5, and BC6, respectively).

BC films with Rhodamine C. (a, b) Photo images of the prepared BC samples (see text for details); (c) PL spectra of the BC1 (curve N1), BC3 (N3), BC4 (N4), and BC5 (N5) samples. (d) PL spectra of the samples BC4 (curve 1) and BC6 (curve 2). The PL spectrum of the Rhodamine C is shown for comparison (curve 3 in Figure 9d); room temperature, λex = 473 nm [292]. Adapted from [292]. © The Author(s). Distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The PL spectra of BC films measured under excitation at λex = 473 nm are shown in Figure 9b, c. The spectrum of the bleached BC film (curve N3 in Figure 9b) is typical for cellulose-based materials described earlier in this paper. Incorporation of the Rhodamine C into BC film leads to domination of the yellow component of the spectra (curves N4 and N5 in Figure 9c; 1, 2 in Figure 9d). From a comparison of these spectra with a spectrum of Rhodamine C (curve N3 in Figure 9d), it is clear that changes in the spectra are related to the contribution of the dye to the overall spectrum of the composite. Therefore, spectra N4, N5 in Figure 9c and spectra 1, 2 in Figure 9d can be considered as superimposed emission from the cellulose matrix and filler—Rhodamine C. It is obvious that the spectrum and visual appearance of the emission of “Rhodamine C”@BC composite films can be varied in a wide range, from white to red light [292].

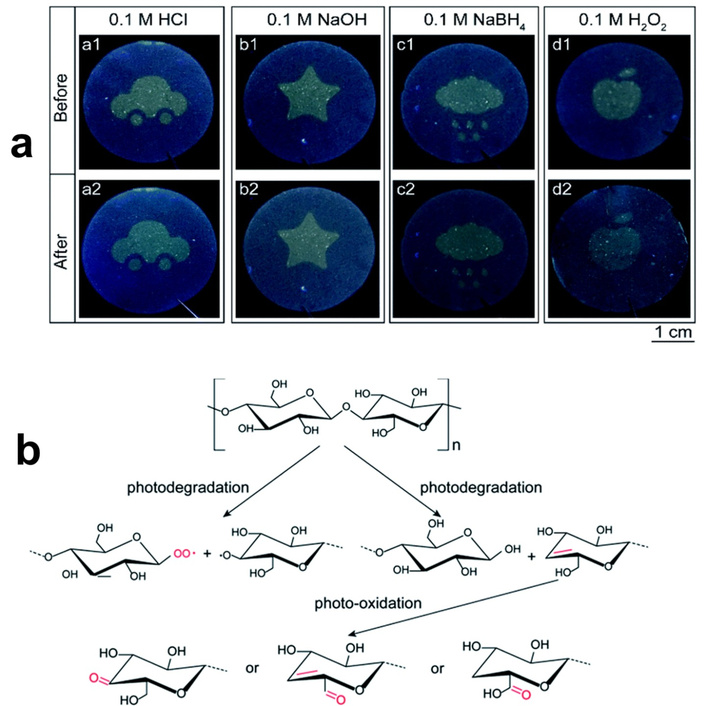

As it was noted above, the own luminescence of the cellulose-containing materials has limited applicability due to low PL intensity and dependence of PL characteristics on various, sometimes uncontrolled, factors. In order to overcome this drawback, different techniques and methods have been applied. Photo-oxidation is one of the simplest methods applied in order to increase the content of carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroperoxide groups, or to decrease the degree of polymerization [293]. All these changes have an influence on the luminescent properties of cellulose-based materials. Cheng et al. [294] applied this method for the formation of luminescent patterns on cellulose nanofiber papers (Figure 10a). It was shown that the samples were covert, solvent-resistant, and chemically stable.

Oxidated cellulose nanofiber papers. (a) Photographs of the cellulose nanofiber paper-based security labels in various solvents: before (top row) and after (bottom row) solvent treatment; (b) scheme of the photochemical formation of fluorescent cellulose nanofiber under UV light irradiation. Adapted from [294]. © 2021 The Author(s). Distributed under a CC-BY 3.0.