Affiliation:

1Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7089-7728

Affiliation:

2Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0109-6000

Affiliation:

1Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4822-0646

Affiliation:

1Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1257-3036

Affiliation:

1Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0745-7591

Affiliation:

1Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA

Email: mdhar@utk.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0610-5351

Explor BioMat-X. 2025;2:101352 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2025.101352

Received: May 24, 2025 Accepted: December 02, 2025 Published: December 08, 2025

Academic Editor: Cornelia Vasile, “P. Poni” Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry, Romania

Aim: Peripheral nerve injuries (PNIs) often result in a diminished quality of life for those affected and are the most common nervous system injury, with limited treatment options. Regenerative medicine presents novel biomaterial and cell-based therapies to repair the damaged tissue. Graphene oxide (GO), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have the potential to serve as components to treat PNI. This study evaluates the systemic toxicity of GO and xenogenic human MSCs by analyzing the peripheral blood immune phenotype when a novel nerve guidance conduit (NGC) is implanted in a rat model for six months.

Methods: A 10-mm long sciatic nerve defect model was created in 8–10-week-old Lewis rats. Four treatment groups were generated: autograft (positive control), poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NGC, PLGA NGC with 0.25% GO, and PLGA/GO NGC seeded with 1 × 106 human adipose-derived MSCs. Tail blood was collected before surgery, and at 24 hours, 2 weeks, 2, 3, 5, and 6 months after surgery. Hematological analyses were carried out to evaluate systemic changes, if any, in peripheral immune cell types, namely, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and macrophages. The treated and contralateral sciatic nerves were excised, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and H&E stained, to identify any local foreign body rejection.

Results: Treatment groups with GO and MSCs displayed percent total values of peripheral immune cells equivalent to the autograft at each time point. There was no evidence of an inflammatory response in the histological samples.

Conclusions: The lack of changes in immune phenotype demonstrates a lack of nanotoxicity of the graphene nanoparticles and no evidence of adverse effects due to the MSCs. This was further supported by a lack of local foreign body response at the site of implantation. Overall, the PLGA/GO NGC + MSCs construct is biocompatible for six months in a rat PNI model, exhibiting a potential for clinical translation.

The sensory and motor neurons that compose the peripheral nervous system (PNS) can be easily damaged by a number of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries (PNIs), including penetrating, lacerating, traction, and crush injuries [1, 2]. The gold standard treatment for replacement of lost nerve segments associated with PNIs is the autograft. However, autografts often yield inferior outcomes resulting in incomplete functional recovery in up to 33% of patients who suffer permanent disability [3]. Being the most common type of injury that affects the nervous system, diminished quality of life, and limited treatment options, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine strategies are increasingly being used to treat PNIs. Strategies are aimed at developing novel scaffolds with or without stem cells [2, 4–6]. The focus is to fabricate artificial structures (biomimetic) aimed at nerve regeneration and functional recovery. These are promising alternatives to the autograft; however, their local and systemic biocompatibility must be established prior to their use.

Graphene is a carbon-based nanomaterial whose carbon atoms are covalently bonded and arranged in a honeycomb lattice structure that is a single atom thick. Functionalizing graphene into its oxidized form, graphene oxide (GO), improves its hydrophilicity and decreases nanoparticle aggregation, in turn reducing potential cytotoxicity [7, 8]. GO has favorable physicochemical properties for nerve tissue engineering. For example, its rough surface increases surface area to improve cell attachment, while its numerous hydroxyl and carboxyl groups and properties of electrical conductivity influence cell behavior in favor of functional axon regeneration [8–13]. These properties make GO an excellent addition to polymer-based scaffolds for PNI repair. However, there must be a balance between these properties and the potential toxicity of the nanomaterial when implanted in vivo. Some studies have implanted concentrations (of up to 5 mg/kg) in small animal models and cited adverse effects with nanoparticles aggregating in multiple organs, such as kidney, liver, heart, spleen, intestine, or lungs. Alternatively, other studies have implanted higher concentrations (up to 600 mg/kg) and cited no adverse effects and no signs of aggregation in the same organs [7, 11, 14–16]. These inconsistencies likely are associated with a number of variables, such as surface functionalization, surface charge, particle shape and size, dispersion, concentration, dosage, route of administration, and processing techniques [7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17]. Each variable may influence the biomaterial-cell interface, mediating the immune response to determine biocompatibility [18]. This is critical when developing a translatable treatment for functional nerve repair.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells derived from a range of easily sourced adult tissues, with bone marrow and adipose tissue being the most common [19–22]. MSCs have excellent potential for nerve repair therapeutics, having exhibited immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, neuroregenerative, and angiogenic potential in both in vitro and in vivo models, while also demonstrating an inherent migratory behavior towards sites of injury [6, 21–24]. MSCs can be assessed for trilineage differentiation, proliferation, and have a standard set of expressed surface markers to determine that the appropriate cell type has been isolated [20]. However, there are numerous variables that are not standardized, including cell source, culture media and reagents used, dose and method of administration [19, 24–26]. Though there are no ethical concerns with the use of adult tissue sources, there are other concerns associated with their isolation and expansion [24]. Cell senescence occurs with increasing age of donor tissue, reducing cell potency and increasing risk for developing tumors [19, 20, 25]. Though these risks are minimal in younger, healthy donor tissue, exhibiting a desirable proliferation capacity and minimal immunogenicity is needed when implanting allogenic cells [21, 24].

This study for the first time investigates the biocompatibility of GO, and MSCs when a novel nerve guidance conduit (NGC) is implanted in a rat model for six months. A combination of local and systemic response is being used to evaluate biocompatibility. Both GO and MSCs have been investigated as therapeutic components to treat PNI, due to their unique properties that support functional nerve repair. However, the variability in biocompatibility has caused controversy that has prevented their clinical translation and commercial availability [6, 7, 9, 14, 19, 20, 24, 27, 28]. In all these studies, hematological analyses were not performed. The sciatic nerve defect model reported from our lab presented an in vivo condition in which we could evaluate both the local and the systemic effects of the two components [29]. In order to increase the clinical translatability of these scaffolds, each study had a group of rats which were treated with a construct of scaffold and human adipose tissue-derived MSCs. Human MSCs served as a source of previously isolated, characterized, and cryobanked cells, which were readily available. Additionally, we used poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) as the polymer to fabricate graphene—based nanocomposites. PLGA is FDA approved for clinical applications and hence, increases the translatability of the construct used in the current study.

Towards this goal, this study analyzes changes in the peripheral blood immune phenotype as a method to evaluate the six-month systemic toxicity of a novel NGC composed of 0.25% GO, synthetic polymer PLGA, and seeded with human, adipose-derived MSCs when implanted in a sciatic nerve defect rat model. We hypothesize that the immunophenotypic profile of peripheral rat blood, including T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages, will be equal to the gold standard, i.e., autologous treatment of PNIs, indicating an immune tolerance to our form of GO and MSCs. Determination of the biocompatibility of these components can aid in their clinical translation for use in future nerve repair treatments.

All biochemicals, chemicals, and disposable supplies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) unless otherwise noted. These are standard reagents and disposables routinely used in these types of experiments. These include all tissue culture media, DMEM/F12 with the additives (fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin mixture, plastic disposables, tissue culture–treated plasticware, and the Hanks Balanced Buffer Solution). All antibodies used for flow cytometry were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA) unless otherwise noted, and all antibodies were pre-conjugated, therefore no secondary antibodies were used.

All animals were procured and housed as described earlier [29]. Lewis rats (n = 26) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. All animals (aged 2–3 months) were acclimated prior to beginning procedures. All procedures were conducted in accordance with PHS guidelines for the humane treatment of animals under approved protocols established through the University of Tennessee’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (IACUC# 2574-0921). All animals were individually housed after surgery, had ad lib food, water, and enrichment, and were housed in a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle.

The PLGA/GO NGC was prepared as previously described [29]. Briefly, two thousand milligrams of poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolide) (50:50 lactide:glycolide; MW 30,000–60,000) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 5 mg single layer graphene oxide (Cheap Tubes Inc., Grafton, VT, USA) were blended together with 0.5 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) hybri-max™ (MW 78.13 g/mol) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a scintillation vial to make the 0.25 wt. % (2,500 mg/kg) PLGA/GO blend (0.25% w/w relative to PLGA). The blend was placed in an Isotemp™ hybridization incubator at 85°C for 2.5 hours, at a medium/low rotisserie speed, mixing occasionally. Vial was placed in –20°C freezer overnight. The material was placed into the syringe of the thermoplastic printhead of the Cellink Bio X6™ extrusion-based 3D bioprinter (BICO, Göteborg, Sweden). The dimensions were set to 2.75 mm × 2.75 mm × 15 mm (X × Y × Z) and a 0.2 µm printhead nozzle size was used. The printing parameters were set to 200 kPa pressure, 1 mm/sec speed, and 85°C temperature, and adjusted slightly as needed to produce the NGC. NGCs were sterilized under UV light for 2 hours prior to implantation.

Patient consent was obtained and approved by an IRB protocol at the University of Tennessee Medical Center. Adipose tissue was collected from patients undergoing pannulectomies. Human adipose tissue derived MSCs were isolated, characterized, and expanded as described previously [30–33]. Briefly, adipose tissue was digested at 37°C for 2–4 hours, in a type I collagenase buffer. After a homogeneous tissue solution was obtained, the collagenase was inactivated, and the homogenate was filtered through 100 µm cell strainer. Cells were pelleted via centrifugation at room temperature, 1,500 g for 15 min. The pellet was washed and cells were suspended in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS, and ultimately, seeded in a T75 flask. The collected cells were confirmed to be MSCs using established confirmatory methods as reported earlier [29]. Cell adhesion, morphology, expression of cluster-of-differentiation protein markers, and trilineage differentiation were confirmed as described previously [30–33]. Cells from passage 2–6 were used. One million MSCs were seeded on the scaffolds randomly selected for the PLGA/GO + MSC treatment group.

Animals were divided into four treatment groups: 1) autograft (positive control) (n = 8), 2) PLGA (n = 6), 3) PLGA/GO NGC (n = 6), and 4) PLGA/GO + MSC NGC (n = 6). The sciatic nerve defect peripheral nerve injury model was created by cutting a 10-mm mid-thigh section of the sciatic nerve using standard procedures [29, 34–40]. In brief, the removed sciatic nerve segment was sutured back in place for those in the autograft group. In the remaining three groups, the NGC was sutured in place to bridge the transected proximal and distal ends. Rats were individually housed and monitored until the end of the 6-month study. One animal was removed at the 5-month timepoint due to excessive stress, unrelated to the project. A sample size of n = 6–8 was calculated based on an alpha-error of < 0.05 and a beta-error of < 0.1 for a high statistical power.

The following procedure was performed to collect approximately 0.5 mL of whole blood from each animal. The animal was lightly anesthetized with isoflurane gas. The needle of a 25G x 3/4" SURFLO® winged infusion set (Terumo, Somerset, NJ, USA) was inserted in a tail vein. The tubing was attached to a 1 mL Monoject™ tuberculin syringe (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) and the blood was drawn [41]. The needle was removed, and pressure was applied with gauze to the site. The blood of two to three animals (of the same experimental group) was pooled into a single 1.3 mL micro sample tube EDTA K3E (Sarstedt AG & Co., Nümbrecht, Germany). The samples were refrigerated until beginning the antibody staining. The procedure was performed prior to the sciatic nerve defect and NGC implantation surgery, within 24 hours after the surgery, 2-weeks after the surgery, and at 2-, 3-, 5-, and 6-month study timepoints to evaluate the effects on circulating peripheral immune cells.

Each pooled rat peripheral blood sample was separated into nine centrifuge tubes with 100 µL whole blood per tube. Tubes were labelled I–IX, each associated with a specific group of fluorescent-tagged monoclonal antibodies. Each antibody was selected to address a general panel targeting T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, NK cells, and myeloid cells, followed by lineage-specific markers to target additional immune cell sub-types that would be indicative of a foreign body rejection should the implanted materials be incompatible (Table 1). Two milliliters 1X Erythrolyse red blood cell lysing buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was added to each sample for 10 minutes at room temperature. ACK lysing buffer (catalog #A10492-01) was used for the 2-week timepoint due to chain supply issues. Samples were washed twice with 1% PBS/BSA. Antibodies were added, as follows: group I—mouse anti rat CD3: FITC or CD3 monoclonal antibody (clone 1F4) eBioG4.18, FITC, eBioscience™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (0.1 mg/mL; 0.5 mg/mL), and mouse anti rat CD45RA: RPE monoclonal antibody (clone OX-33) (1.0 mg/mL); group II—mouse anti rat CD11b: Alexa Fluor® 488 monoclonal antibody (clone OX-42) (0.05 mg/mL) and mouse anti rat CD161: RPE monoclonal antibody (clone 10/78) (1.0 mg/mL); group III—mouse anti rat CD4 (domain 1): Alexa Fluor® 488 monoclonal antibody (clone W3/25) (0.05 mg/mL) and mouse anti rat CD8 alpha: RPE monoclonal antibody (clone OX-8) (1.0 mg/mL); group IV—mouse anti rat MHC class II RT1B: RPE monoclonal antibody (clone OX-6) (1.0 mg/mL) and mouse anti rat IgM heavy chain: FITC monoclonal antibody (clone MARM-4) (1.0 mg/mL); group V—mouse anti rat CD11b: Pacific Blue® monoclonal antibody (clone OX-42) (0.05 mg/mL), mouse anti rat MHC class II RT1B: FITC or RT1.B monoclonal antibody (clone OX-6), FITC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (0.1 mg/mL; 0.1 mg/mL), and mouse anti rat CD86: RPE or CD86 (otherwise known as B7-2) monoclonal antibody (clone 24F), PE, eBioscience™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (1.0 mg/mL; 0.2 mg/mL); group VI—mouse anti rat CD68: Alexa Fluor® 488 monoclonal antibody (clone ED1) (0.05 mg/mL), mouse anti rat CD11b: Pacific Blue® monoclonal antibody (clone OX-42) (0.05 mg/mL), and mouse anti rat CD163: RPE monoclonal antibody (clone ED2) (0.5 mg/mL); group VII—mouse anti rat CD43: FITC monoclonal antibody (clone W3/13) (0.1 mg/mL); group VIII—unstained control; group IX—mouse anti rat CD45: Alexa Fluor® 488 monoclonal antibody (clone OX-1) (0.05 mg/mL). Samples were washed with 1% PBS/BSA. Samples were resuspended in 200 µL cold (4°C) PBS. Samples were transferred to culture tubes with 1 mL 1X Attune™ Focusing Fluid. Samples were run on the Attune NxT Acoustic Focusing Cytometer [42]. The cytometer was standardized per manufacturer protocols, cell count was standardized to 40,000 cells per sample, and the settings were maintained for all samples. Files of the graphs and the summary table were obtained for statistical analysis.

Panel of fluorescent-tagged monoclonal antibodies and their immune-cell subtype targets.

| Group | Antibodies | Cell types |

|---|---|---|

| I | CD3 (FITC) + CD45RA (RPE) | B Lymphocytes, T Lymphocytes |

| II | CD11b (A488) + CD161 (RPE) | Natural Killer Cells, Macrophages + Monocytes + Dendritic Cells + Granulocytes |

| III | CD4 (A488) + CD8a (RPE) | Cytotoxic T-Cells + Natural Killer Cells, Helper T-Cells + Monocytes |

| IV | RT1B (RPE) + IgM (FITC) | B Lymphocytes |

| V | CD11b (Pacific Blue) + RT1B (FITC) + CD86 (RPE) | Macrophages + Monocytes + Dendritic Cells + Granulocytes, Dendritic Cells + Macrophages + B Lymphocytes |

| VI | CD68 (A488) + CD11b (Pacific Blue) + CD163 (RPE) | Macrophages, Macrophages + Monocytes + Dendritic Cells + Granulocytes |

| VII | CD43 (FITC) | Leukocytes |

| VIII | Unstained control | N/A |

| IX | CD45 (A488) | Leukocytes + B Lymphocytes |

Samples of rat peripheral blood were divided and stained with fluorescent-tagged monoclonal antibodies. Each antibody targeted a specific protein associated with an immune-cell subtype. The mean fluorescence was quantified as a percentage of the total of 40,000 cells per sample.

The effects of treatment and time on immune cells and cytokines were examined using mixed model analysis for repeated measures with treatment, time and their interaction as fixed effects while subject nested within treatment as the random effect. Ranked transformation was applied because diagnostic analysis on residuals exhibited non-normality and unequal variance using Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene’s test. Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed with Tukey’s adjustment. Statistical significance was identified at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 TS1M8 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC). Data was entered into GraphPad Prism (version 10) for visualization and graph generation.

As previously described, at the 6-month end-of-study timepoint, the sciatic nerve was excised from the defect site [29]. Briefly, each tissue was aligned on cardboard and placed in a tissue embedding cassette in 10% formalin. Tissues were paraffin embedded and longitudinally sectioned. One histology section from each rat was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Azer Scientific, Inc., Morgantown, PA, USA) for assessment of cellular detail. The H&E sections were analyzed by a trained histologist for local adverse effects. Sections were imaged using Keyence BZ-X Series All-In-One Fluorescent Microscope (Keyence Corporation of America, Itasca, IL, USA) at 5× magnification.

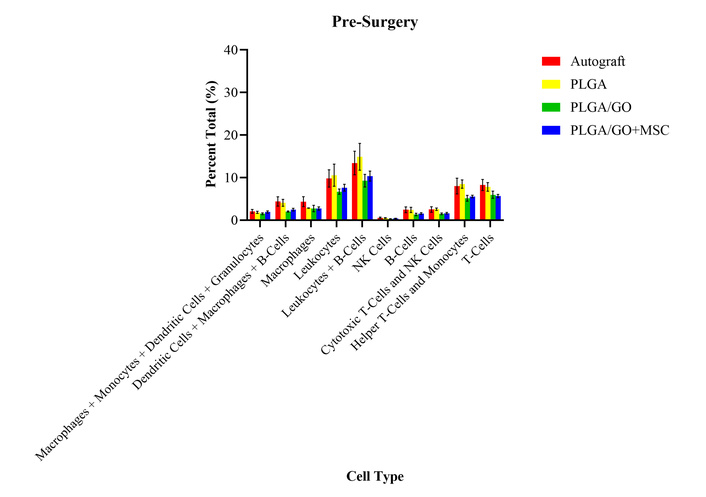

At the baseline draw before surgery, there were no statistically significant differences between the percent total values of any of the treatment groups for all cell types (Figure 1). Throughout our study, we compared the autograft group to the three experimental groups (PLGA, PLGA/GO, and PLGA/GO + MSC) to identify changes in the immunoprofile that correlate with the addition of GO and/or MSCs. Additionally, we compared each of the immune cell types at the various timepoints to the presurgical levels in order to identify temporal changes over the 6-month period.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at the pre-surgery timepoint. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

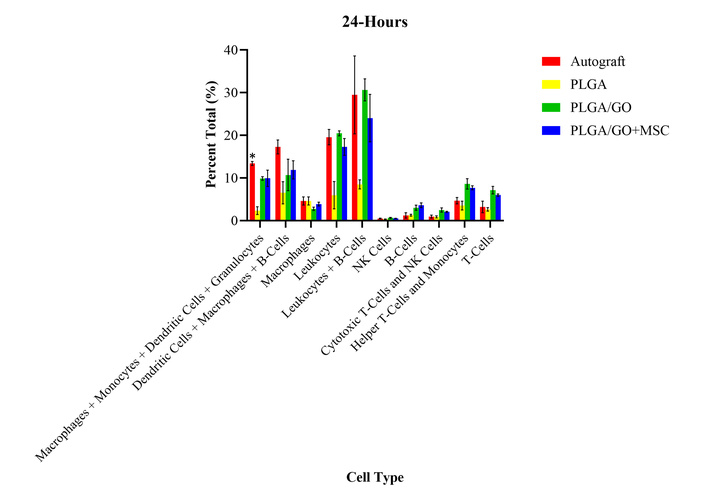

At 24 hours, only the autograft group had a statistically significant increase in percent total values of granulocytes as compared to the PLGA group, and the presurgical levels (Figure 2). There were no significant differences between any of the treatment groups or presurgical levels for any other cell type evaluated at 24 hours after surgery. The lack of differences identified between the treatment groups may determine that there was no immediate adverse effects or foreign body rejection after implantation of the GO and MSCs. However, it was unexpected that there were no significant differences from the presurgical levels as there is an expected immune response from a surgical procedure. The lack of immune response may be due to the medications that the rats received during the procedure and the days following.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 24-hours after surgery. The autograft group had a statistically significant (*) increase in percent total values of granulocytes as compared to the PLGA group and the presurgical levels. There were no other significant differences identified.

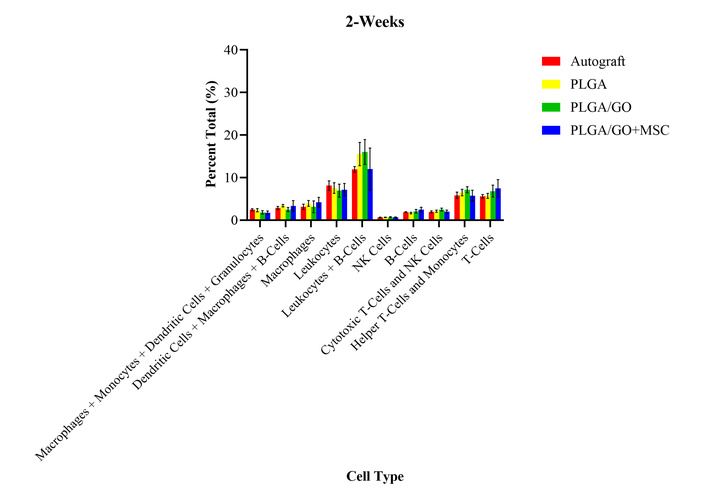

A 2-week timepoint was performed to evaluate the immune response after all medications had been stopped. There were no significant differences between the treatment groups or the presurgical levels for any of the cell types evaluated at 2 weeks after surgery (Figure 3). The lack of differences identified between the treatment groups may further indicate that there were no immediate adverse effects or foreign body rejection after implantation of the GO and MSCs. The lack of differences identified from the presurgical levels may indicate that an immune response is not continuing to be masked by the medications. Histology was performed on the sciatic nerve sections at the end of the six-months to evaluate local immune response, as detailed in an adjacent study [29]. While there was no evidence of a local immune response at 6-months after implantation (Figure 4), future studies may evaluate the histology at the 24-hour and 2-week timepoints to evaluate these differences more closely for foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) and acute signs of rejection [29].

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 2-weeks after surgery. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

H&E-stained sections of the sciatic nerve tissue at the 6-month end-of-study timepoint. (A) Uninjured tissue (of the contralateral hindlimb); (B) the autograft group; (C) the PLGA group; (D) the PLGA/GO group; and (E) the PLGA/GO + MSC group. No material rejection or local adverse effects were identified in any of the tissue sections. Images taken at 5× magnification.

At 2 months after surgery, all treatment groups had significantly increased percent total values of leukocytes, macrophages, monocytes, helper T-cells, and granulocytes as compared to presurgical values (Figure 5). All treatment groups had significantly decreased percent total values of B lymphocytes, NK cells, and cytotoxic T-cells as compared to presurgical values. There were no significant differences between the percent total values of dendritic cells for all treatment groups, as compared to presurgical levels. A challenge occurred at the monthly timepoints that resulted in a change in protocol to aid in red blood cell lysis. The protocol change was incorporated at the 2-, 3-, 5-, and 6-month timepoints. This may explain some of the temporal differences between the monthly timepoints and the baseline percent values. However, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups for any of the cell types evaluated at 2 months after surgery. The lack of differences between the treatment groups may indicate that there were no long-term or chronic adverse effects after the implantation of the GO and MSCs.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 2-months after surgery. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

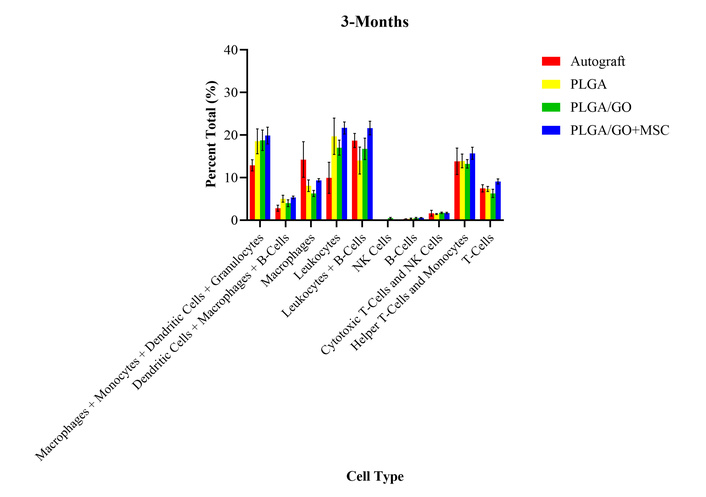

At 3 months after surgery, the PLGA and autograft groups had significantly decreased percent total values of B lymphocytes as compared to presurgical levels (Figure 6). However, regarding B lymphocytes, the PLGA/GO and PLGA/GO + MSC groups had no significant differences between any of the treatment groups and presurgical levels. The PLGA/GO + MSC group had significantly decreased percent total values of leukocytes and increased percent total values of T lymphocytes, as compared to presurgical levels. However, regarding leukocytes and T lymphocytes, the autograft, PLGA, and PLGA/GO groups had no significant differences between any of the treatment groups and presurgical levels. All treatment groups had significantly increased percent total values of monocytes and granulocytes, and significantly decreased percent total values of macrophages and NK cells, as compared to presurgical levels. There were no significant differences between the percent total value of dendritic cells for all treatment groups, as compared to presurgical levels. As compared to the 2-month timepoint, all cell types remained unchanged except for the macrophages and cytotoxic T-cells, which became no longer statistically different from presurgical values. Despite the temporal differences for specific cell types, there were no significant differences between any of the treatment groups evaluated at 3 months after surgery. The lack of differences between the treatment groups may further indicate that there were no long-term or chronic adverse effects after the implantation of the GO and MSCs.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 3-months after surgery. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

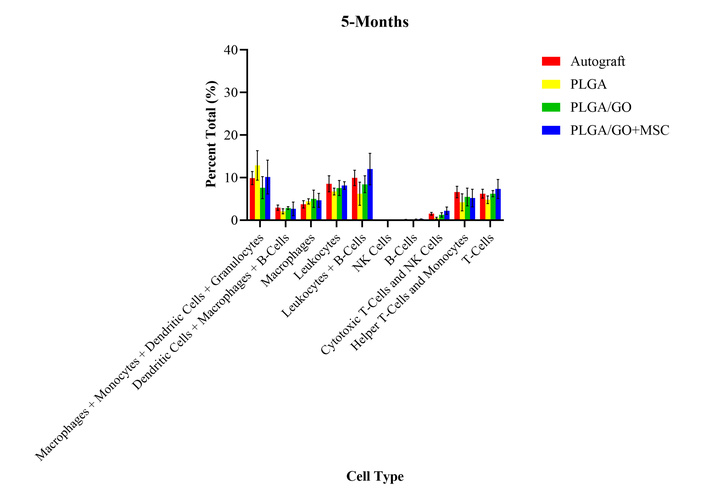

At 5 months after surgery, all treatment groups had significantly increased percent total values of monocytes, dendritic cells, and granulocytes as compared to presurgical levels (Figure 7). All treatment groups had significantly decreased percent total values of B lymphocytes and NK cells as compared to presurgical levels. There were no significant differences between any of the treatment groups or presurgical levels for any other cell type evaluated at 5 months after surgery. As compared to the 3-month timepoint, all cell types remained unchanged except for the helper T-cells, which became no longer statistically different from presurgical values. The lack of differences between the treatment groups continues to provide evidence for no long-term or chronic adverse effects after the implantation of the GO and MSCs.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 5-months after surgery. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

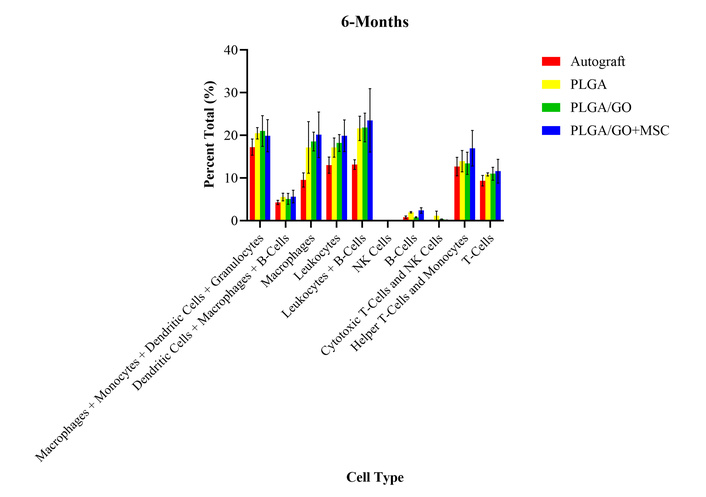

At 6 months after surgery, all treatment groups had significantly increased percent total values of macrophages, monocytes, and granulocytes as compared to presurgical levels (Figure 8). All treatment groups had significantly decreased percent total values of NK cells as compared to presurgical levels. There were no significant differences between any of the treatment groups or presurgical levels for any other cell type evaluated at 6 months after surgery. As compared to the 5-month timepoint, all cell types remained unchanged except for the macrophages and cytotoxic T-cells, which increased and decreased, respectively to the 2 month post-surgery levels. The lack of differences between the treatment groups continues to provide evidence for no long-term or chronic adverse effects after the implantation of the GO and MSCs.

Percent total values of ten groups of immune cells and cell subtypes for the four treatment groups at 6-months after surgery. There were no statistically significant differences between any of the treatment groups for all cell types.

Due to their favorable and tunable properties, carbon-based nanomaterials, specifically, graphene and its derivatives, have been studied for biomedical applications, including therapeutics, diagnostics, and drug delivery [43, 44]. Graphene’s hydrophobicity often results in the material’s functionalization into new forms, including one of the most common forms, GO. While GO exhibits excellent potential as a tissue engineering component for functional nerve repair, as of yet, GO has not been widely used in clinical applications because of concerns for potential cytotoxicity [43]. GO cytotoxicity is highly variable and relies on numerous factors, including surface functionalization, surface charge, particle shape and size, dispersion, concentration, dosage, route of administration, and processing techniques [7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17]. In a previously reported study, we developed a novel PLGA/GO NGC as a PNI treatment modality [29]. In this study, we assessed this specific formulation of graphene nanoparticles for biocompatibility over a six-month period [29]. In this study, we also assessed the in vivo immune response to xenografted, human, adipose-derived MSCs in a rat model. Similar to GO, MSCs have excellent potential in therapeutics, yet raise concerns of adverse patient response regarding cell source, culture media, and reagents used, dose, and method of administration [19, 21, 24, 26].

The immune system’s response to a nerve injury is inflammatory, with a limited ability for self-repair depending on the site, severity, and type of injury that occurs [2, 45]. After a nerve is injured, Wallerian degeneration, slow nerve growth, and retraction of disconnected tissue can occur. These degenerative elements can worsen with the addition of incompatible materials. The presence of incompatible materials can further enhance inflammation, resulting in a foreign body rejection. Specifically, when a biomaterial is implanted, the individual’s plasma proteins adsorb to the biomaterial surface. The innate immune response, including granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells, is the first line of defense and is recruited to the site of insult within hours. Immunoprofiling can be used to gauge the intensity of this response. During this acute inflammatory response, a granulocyte subset, neutrophils, will infiltrate the surrounding tissue to clear debris and activate an immune response. Neutrophils phagocytize the foreign body, secrete antimicrobial factors, and form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). When activated, neutrophils release cytokines and chemokines to recruit monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, as well as cells associated with the adaptive immune system, including T and B lymphocytes, occurring days later. The circulating monocytes have a phagocytic function and are activated when there is a transition from acute to chronic inflammation, differentiating into macrophages, which play a crucial role in early healing [46–49]. Macrophages also use phagocytosis to defend against pathogens. These cells can display a primarily pro- or anti-inflammatory phenotype, which modulates the microenvironment. Macrophages naturally survey areas of damage, striving to preserve tissue integrity. However, when macrophages continuously fail to phagocytize implanted biomaterial, the macrophage membranes fuse to form FBGCs. When a biomaterial fails to integrate, FBGCs cause a fibrous encapsulation, promoted by a chronic inflammatory environment [13, 17, 27, 46, 48, 50, 51]. Meanwhile, dendritic cells work with the innate and adaptive immune systems. Dendritic cells are antigen presenting cells that induce naïve T lymphocyte activation and differentiation, while also engaging with NK cells and B lymphocytes. NK cells play a role in killing abnormal cells. B lymphocytes express diverse forms of antibodies that act on antigen recognition receptors to activate additional immune cells. Finally, T lymphocytes, including the subsets cytotoxic, helper, and regulatory T-cells, fight against infections by releasing cytokines [17, 48]. For example, helper T-cells release pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines to activate or inhibit, respectively, macrophage function [48, 51]. Overall, there is evidence that MSCs and GO can immunomodulate various cytokines and chemokines associated with this process to prevent foreign body rejection, while simultaneously promoting a more favorable microenvironment for nerve repair and regeneration. However, the mechanisms of this immune response and the precise conditions that affect a favorable outcome remain poorly understood [6, 48, 52]. The involvement of each of these immune cell types in the acute and chronic response to the implantation of foreign materials is why we chose to identify the immunoprofile of each treatment group at each timepoint in this study.

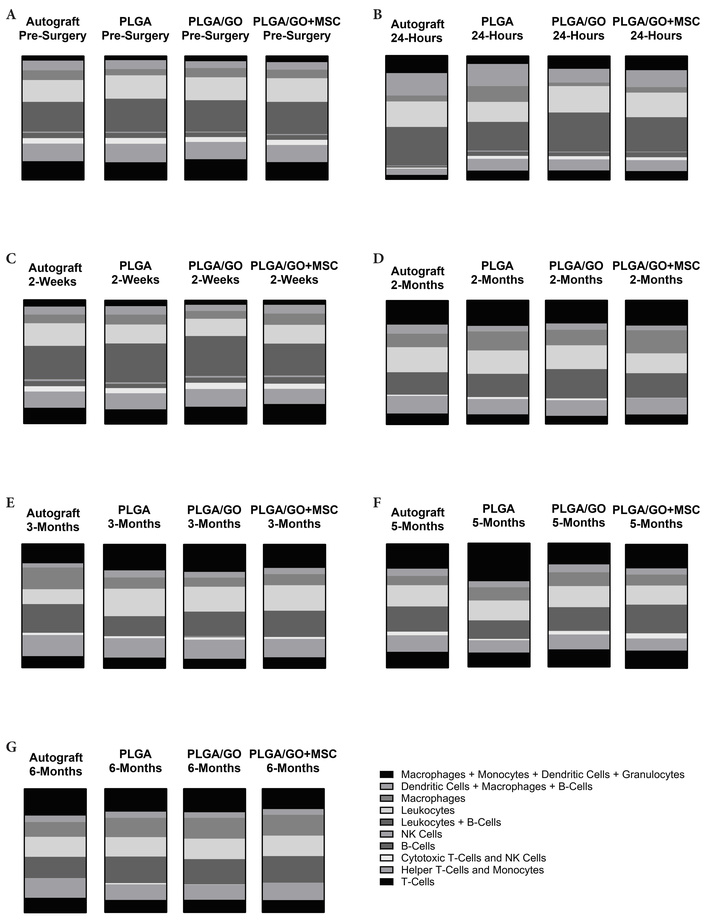

Our data support the fact that MSCs and GO exhibit immunomodulatory properties, while presenting a microenvironment favorable for tissue engineering [6, 48, 51, 52]. Our data for the first time reports a global view of changes in the systemic levels of a multitude of immune cell biomarkers when a specific graphene derivative and xenogenic MSCs are implanted in an animal model. The immunoprofiles of all treatment groups were similar to those observed in the autograft-treated rats (Figure 9). This study builds a foundation to confirm that the two modalities are safe. Future experiments focused on the evaluation of the interactions between graphene nanoparticles with the immune cells themselves should be undertaken.

The changes in the percent total values of the fluorescent expression for ten groups of immune cells. For each of the four treatment groups, at the (A) pre-surgery, (B) 24-hour, (C) 2-week, (D) 2-month, (E) 3-month, (F) 5-month, and (G) 6-month timepoints. Graphs represent all data gathered from the immunophenotyping analysis at each of the 7 timepoints. The key conveying the ten immune cell groups was derived from the data points generated by each individual sample run on the flow cytometer. Each graph visualizes the average percent total value for that treatment group and timepoint based on the mixed model statistical analysis performed. Significance was also determined based on the mixed model statistical analysis. While some significant temporal changes were identified, there were no significant differences in the percent total values between the treatment groups at each timepoint (Figure made with GraphPad Prism).

The immunophenotyping analysis created an immunoprofile for each treatment group at each timepoint to evaluate in vivo foreign body reactions to our implanted GO nanoparticles and xenogenic human MSCs. There were no significant differences between the various animal groups for all cell types at all timepoints. This information was confirmed with H&E histology, which showed no local adverse effects or foreign body rejection at the site of repair. With this information, we can confidently state that all the components, polymer PLGA, nanoparticles (GO), cells (MSCs), or their combinations used in this animal model were biocompatible. Specifically, the novel NGC, containing GO, 3D printed at 0.25 wt. %, seeded with or without xenogenic, human, adipose derived MSCs, and implanted at the site of a sciatic nerve injury, did not cause acute or chronic adverse effects or foreign body rejection up to 6 months in rats. While there were some temporal changes over the six-month period, changes were expected with natural immune system range and variation. With the proposed PLGA/GO + MSC NGC for PNI repair addressing safety concerns using an in vivo rat model, future studies will test the NGC in large animal models and clinical studies.

FBGCs: foreign body giant cells

GO: graphene oxide

MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells

NGC: nerve guidance conduit

NK: natural killer

PLGA: poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

PNI: peripheral nerve injuries

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Xiaocun Sun in running the statistical analysis. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Robert Donnell for analysis of the H&E-stained histological slides. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Lisa Amelse in performing the antibody staining. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Stacey Stephenson in performing the sciatic nerve defect surgery. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Tom Masi in seeding the MSCs on the scaffolds. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Angela Kites in figure visualization. Dr. Mohamed Abouelkhair is now affiliated with Rowan University’s Shreiber School of Veterinary Medicine (Department of Diagnostic Medicine and Pathobiology, Glassboro, NJ 08028, USA) following the completion of this research, which was conducted while at the University of Tennessee. Briana Lewis is now affiliated with Mississippi State University (Department of Animal Science, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA) following the completion of this research, which was conducted while at the University of Tennessee.

MEHT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MAA: Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. SDN: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. BL: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. DEA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors consent to publication.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

The study complied with the 2024 Helsinki Declaration and “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. All procedures were conducted in accordance with PHS guidelines for the humane treatment of animals under approved protocols established through the University of Tennessee’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (IACUC# 2574-0921). The human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells used for the experiments described in this manuscript were derived from adipose tissue collected from patients undergoing pannulectomies at the University of Tennessee Medical Center. The collections were performed under an approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol (IRB#3995). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, per the IRB protocol.

Patient consent was obtained in accordance with the IRB-approved protocol at the University of Tennessee Medical Center.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This article was funded by the University of Tennessee: Office of Research, Innovation, and Economic Development Seed Award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 955

Download: 16

Times Cited: 0