Affiliation:

Department of Research, Molecular BioInsights, Winchester, MA 01890, USA

Email: doricke@molecularbioinsights.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2842-2809

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2025;3:100983 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2025.100983

Received: March 27, 2025 Accepted: May 19, 2025 Published: May 29, 2025

Academic Editor: Uday Kishore, University of Oxford, England

The article belongs to the special issue Innate Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Diseases

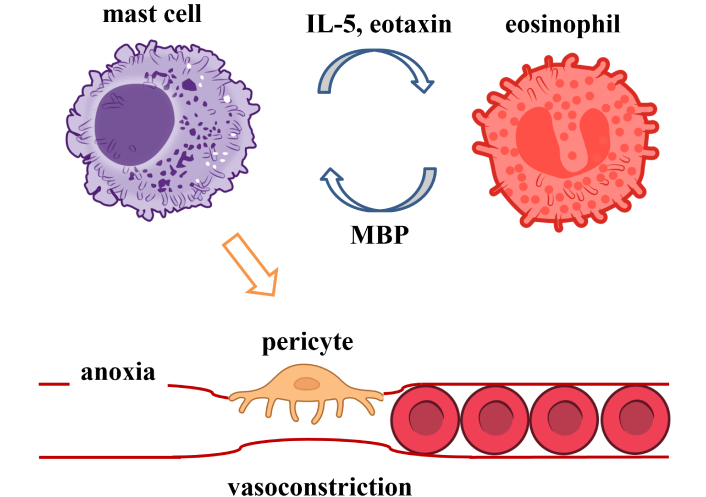

Activation of eosinophils and mast cells in dysregulated type 2 immunity may play key roles in allergic diseases. Eosinophils are linked to the pathobiology of multiple human diseases, including eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs), functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), Kimura’s disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), rheumatoid lesions, allergy, asthma, and some forms of heart disease etc. Eosinophils are part of the innate immune response involved in combating multicellular parasites and some infections. Mast cells play a key role in allergies, allergic conjunctivitis, allergic dermatitis (eczema), allergic rhinitis (hay fever), anaphylaxis, asthma, and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). Mast cells can also play a key role in eosinophilic diseases. Eosinophils respond to interleukin 5 (IL-5) and chemotactic chemokine eosinophil chemotactic factor (eotaxin) released from activated mast cells. Mast cells can be activated by fragment crystallizable (Fc) receptor bound immunoglobulin E (IgE) and G (IgG) antibodies bound to allergens and viruses. Cross talk between eosinophils and mast cells can result in chronic inflammations or eosinophilias. Vasoconstriction of capillaries by histamine contracted pericytes is also predicted to contribute to a subset of these diseases. This article proposes that for these diseases, activation of mast cells is a key step in disease pathogenesis. Targeting activated mast cells in these diseases are potential adjunctive therapies to evaluate in clinical studies. A review of relevant eosinophilia literature is presented that supports the role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of multiple allergic and eosinophilia diseases.

Both mast cells and eosinophils appear to play key roles in multiple allergies and diseases, with type 2 immunity playing a key role. Type 2 immunity is a branch of the adaptive immune system for defending against large parasites. Dysregulated type 2 immunity responses include activation of eosinophils and mast cells, T helper 2 (Th2) cells, and multiple cytokines. The eosinophil granule major basic protein (MBP) activates mast cells and basophils [1]. Eosinophils also play a role in response to some infectious diseases and allergic responses. Overall, eosinophils play key pathobiological roles in allergic diseases [2]/allergic inflammation [3], allergic rhinitis (reviewed) [4, 5], eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) [6], functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) [7], Kimura’s disease [8], hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) [9], rheumatoid lesions/rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [10], allergy [3], asthma [11, 12], eosinophilic asthma [13], systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia (SMCD-eos) [14], and some forms of heart disease including chronic heart failure (CHF) [15] and eosinophilic myocarditis (EM) [16] (Table 1). EGIDs are a group of disorders encompassing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) [17], eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE)/eosinophilic enteritis (EE), including eosinophilic gastritis (EG), and eosinophilic colitis (EC). Eosinophils respond to interleukin 5 (IL-5), eosinophilic chemotactic factor (eotaxin), and other chemokines released by innate and adaptive immune cells. Eotaxin and IL-5 are released from activated mast cells; mast cells play a key role in allergy [18, 19], allergic conjunctivitis [20], allergic/contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis (AD) (eczema) [21], allergic rhinitis (hay fever) [22], anaphylaxis [23], asthma [18], EGIDs [6], FGIDs [24], Kounis syndrome (KS) [25, 26], mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) [27], and mastocytosis [28]. Mast cells and eosinophils may play a key role in tissue remodeling and angiogenesis during allergic diseases [29], multiple allergies, and diseases. IL-5 also plays key roles in multiple cell types involving airway type 2 inflammation, as reviewed [30].

Eosinophils and mast cells in diseases

| Disease | Eosinophils | Mast cells |

|---|---|---|

| allergic conjunctivitis | Yes | Yes |

| allergic inflammation | Yes | Yes |

| allergic/contact dermatitis | Yes | Yes |

| allergic cutaneous vasculitis (hypersensitivity vasculitis/cutaneous small vessel vasculitis) | Yes | Yes |

| allergy | Yes | Yes |

| anaphylaxis | Yes | Yes |

| asthma | Yes | Yes |

| atopic dermatitis (AD) (eczema) | Yes | Yes |

| chronic heart failure (CHF) | Some | Some |

| cutaneous necrotizing venulitis | Yes | Yes |

| eosinophilic asthma | Yes | Yes |

| eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) | Yes | Yes |

| eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) (Churg-Strauss syndrome) | Yes | Yes |

| eosinophilic pancreatitis (EP) | Yes | Yes |

| EGID: eosinophilic colitis (EC) | Yes | Yes |

| EGID: eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) | Yes | Yes |

| EGID: eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE)/eosinophilic enteritis (EE) | Yes | Proposed |

| functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) | Yes | Yes |

| hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) | Yes | Yes |

| Kimura’s disease | Yes | Significantly increased; possible role |

| Kounis syndrome (KS) | Yes | Yes |

| mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) | Elevated; complex relationship | Yes |

| mastocytosis | Yes | Yes |

| rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | Yes | Yes |

| systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia (SMCD-eos) | Yes | Yes |

Herein, I propose that mast cells play an important role in the disease pathogenesis of allergies, asthma, a subset of eosinophilias, and some forms of heart disease. Coupling of both cell types in diseases has been described previously for mast cell disease by Kovalszki and Weller [31]. Frequently, mast cells are activated by antibodies bound to Fc receptors. Histamine released by mast cells may induce localized ischemia from contracted pericytes [32] in a subset of these diseases (Figure 1). Targeting activated mast cells in these diseases may be used as an adjunctive therapy to enhance existing eosinophilia treatment protocols. Alternatively, targeting IL-5 or IL-5R may provide benefits. Several IL-5 and IL-5R antibodies have been approved to treat severe asthma, including: mepolizumab (IL-5), reslizumab (IL-5), and benralizumab (IL-5Rα). Mepolizumab is also approved for treating eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and HES.

Eosinophils and mast cells’ involvement in multiple disorders is reviewed in the following sections: allergies, asthma, EC, EoE, EGE, EG, EGPA, eosinophilic pancreatitis (EP), FGIDs, HES, heart disease, and Kimura’s disease.

Allergies are damaging hypersensitive immune responses to exposures to a substance, especially pollen, fur, a specific food, dust, etc. Eosinophils and mast cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic diseases, including: allergy, AD, cutaneous necrotizing venulitis, and drug-induced immune responses. AD is a chronic inflammatory skin disease involving IgE, mast cells, and eosinophils [37]. The role of eosinophils involvement in AD is reviewed by Simon et al. [38]. The mast cell may be a central modulator of events in allergic cutaneous vasculitis [39]. Mast cells were also identified in allergic vasculitis induced by long-term hydrochlorothiazide use [40]. Early massive degranulation of mast cells, followed by sequential infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, was observed in a patient with cutaneous necrotizing venulitis [41]. Allergies are frequently treated with steroids and antihistamines. In addition, the mast cell stabilizer, oral sodium cromoglycate, has been used to successfully treat a patient with gastrointestinal allergy [42].

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition characterized by recurring episodes of shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and chest tightness. Increased eosinophils have been reported to be associated with asthma [11], pathophysiology (reviewed) [43], possible asthma exacerbation (reviewed) [44], and tissue remodeling (reviewed) [45]; mast cells and eosinophils are associated with severe asthma in children [46]. Subjects with allergic disorders are at a significant risk for developing high intima-media thickness and atherosclerosis with involvement of mast cells and leukotrienes [47]. In some individuals with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can trigger an asthma attack or worsen existing symptoms. IgE antibodies plays a key role in parasitic infections and also allergic reactions. Asthma treatments are primarily inhaled medications containing anti-inflammatory medications and bronchodilators that relax airway muscles. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab significantly reduced the rate of asthma exacerbations by 38% (P < 0.0001) [48]. Better clinical response to anti-inflammatory corticosteroid treatment was observed for asthma patients with mast cell subtypes that express both tryptase alpha/beta 1 (TPSAB1) and carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3) proteases [49]. Due to the need for frequent administration, mast cell stabilizers are not preferred for treating asthma. Recent advances in treating eosinophilic asthma have been reviewed [50, 51].

EC is a rare disease of the colon or large intestine. Colonic eosinophilia can also occur secondary to helminthic infections, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease, food allergies, celiac disease, HES, drug reactions, and allergic diseases, including rhinitis, asthma, sinusitis, dermatitis, food allergies, eczema, urticarial, or atopic conditions [52]. EC presents with a bimodal age distribution in infants associated with bloody diarrhea or young adults with chronic relapsing colitis [53]. EC treatment focuses on reducing inflammation and relieving symptoms.

EoE is an immune-mediated, antigen-driven disease characterized by pathogenic eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus leading to clinical symptoms [54]. Elevated eosinophil (reviewed) [55, 56] and mast cell counts [57] are observed in EoE [1], and also mast cell degranulation [58]. Mast cell infiltration is limited to the epithelium [59]. In a prospective cohort study, 24/96 (25%) of EoE cases had a mast cell to eosinophil ratio > 1 [60]. An experimental mouse model found that mast cells had no influence on promoting EoE but played a significant role in muscle cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy [61]. Mast cells can be activated by food allergies associated with IgE antibodies. Food and aeroallergens appear to activate a Th2 immune response with elevated IL-13, IL-5, and eoxin-3 [62]. Targeting mast cells, fourteen EoE patients were treated with cromolyn sodium, a mast cell stabilizer (100 mg four times daily) without improvement [63]. A retrospective study of 381 EoE patients found that medications such as oral corticosteroids are effective, but EoE recurs upon withdrawal of treatment [63]. Targeting IL-5, anti-IL-5 antibody treatment has been shown to reduce mast cell/eosinophil couplets in patient esophageal biopsies [64, 65]. Patients are responsive to topical glucocorticoids and dietary elimination therapy.

EGE, also known as EE, is a rare eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder of unknown etiology characterized by an eosinophil infiltrate of the intestinal mucosa. Possible triggers of EGE include food allergies, infections, medications, and autoimmune disorders. Elevated IgE is observed in EGE [66]. Cello et al. [67] propose that food antigen IgE antibodies bound to mast cells’ Fc receptors release histamine and eosinophil attractant chemokines. Activated mast cells are a potent source of IL-5 in the human intestinal mucosa [68]. Oral cromolyn/sodium cromoglycate [69, 70], and ketotifen, a second-generation H1-antihistamine, have been used as a safe and effective alternative steroid-sparing agent to traditional systemic corticosteroids [71, 72] and montelukast sodium [targets cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1R) involved in inflammation] [73, 74] for treating EGE. Biologics are being evaluated for treating EGE, reviewed [75].

EG is a manifestation of EGE. EG is a rare disease characterized by peripheral eosinophilia, eosinophilic infiltration of the bowel wall, and gastrointestinal complaints (abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting). While the etiology of EG is unknown, food and/or environmental allergies may play a role. Patients with EG exhibit IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation [76]. Current treatments include diet change; however, the disease responds inconsistently to dietary elimination therapy. Further treatments include steroids such as prednisone [77], and limited success with oral cromolyn/sodium cromoglycate [69, 70, 77], histamine H1 receptor antagonist ketotifen [78], and montelukast sodium [73].

EGPA (formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome) may be a Th2-mediated disease that activates eosinophils. EGPA is characterized by late-onset asthma, eosinophilia, and vasculitis [79]. Vaglio et al. [80] note that 38% of EGPA patients in two studies had antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). The etiology of EGPA is unknown; factors that may contribute to the development of EGPA include asthma, allergies, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and genetic predisposition. There is a reported case of a patient with asthma who subsequently developed Churg-Strauss syndrome after omalizumab treatment [81]. EGPA treatment focuses on reducing inflammation and relieving symptoms. Biologic options are currently being evaluated, reviewed [79].

EP is a rare form of pancreatitis characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the pancreas. Food allergies can result in acute pancreatitis involving eosinophils, mast cells, neutrophils, B cells, and T cells. Eosinophils and mast cells are important for the initiation and progression of pancreatitis [82]. EP is often treated with steroids to reduce inflammation and eosinophil count. Additional treatment strategies for EP may include cessation of ingestion of inciting food and the mast cell stabilizer sodium cromoglycate.

FGIDs are a group of disorders characterized by chronic abdominal complaints. Common FGIDs include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional dyspepsia (indigestion), functional constipation, and functional diarrhea. Eosinophils and mast cells play an important role in intestinal functional disease [83] and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [84]. IBS is an FGID caused by ingestion of dietary antigen(s) that stimulate IgE and mast-cell response [85]. Eosinophils and mast cells involved in the activation of ulcerative colitis are starting to be characterized [86]. Treatment for functional dyspepsia often includes a combination of lifestyle modifications and medications to manage symptoms. Functional constipation is typically treated by lifestyle changes, with medication for some cases. Functional diarrhea treatment includes dietary changes, stress management, and medication for some cases.

Idiopathic HES is a leukoproliferative disorder marked by a sustained overproduction of eosinophils without a recognizable cause, with involvement of the bone marrow, cardiac, or nervous system. The cause of HES is often unknown, with potential causes including allergic reactions, infections, autoimmune disorders, certain medications, and malignancies. In HES, mast cells and eosinophils can participate in bidirectional crosstalk as well as direct physical contact [87]. Treatment for HES targets the reduction of eosinophil counts. Treatment options are overviewed by Klion et al. [88]. In addition, supportive care and management of potential complications are important for HES patients.

Eosinophils and mast cells contribute to some forms of heart disease, including CHF, some types of eosinophilias, Kounis syndrome, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Mast cells [89, 90] and eosinophils [91] may contribute to some forms of heart disease, including CHF, some of these types of eosinophilias, and KS [25]. The itchy rash associated with DRESS is likely associated with histamine released by mast cells. Cardiac involvement in DRESS syndrome is variable but can occur in up to 21% of cases [92]. In two cases of intractable cardiac failure, elevated numbers of mast cells were observed [93]; a review of 7 myocarditis case files also found 5/7 (71%) with elevated numbers of mast cells [93]. A mouse model points to a role for mast cells in CHF [94]. Inhibition of mast cells by interlukin-10 gene transfer contributes to protection against myocarditis in rats [95]. Th2-type and IL-4 responses are associated with increased neutrophil and mast cell numbers in coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)-induced myocarditis [96]. In addition, histamine plays a role in provoking coronary artery spasm (CAS) in variant angina pectoris [97]. This is supported by the therapeutic addition of famotidine, a histamine H2 receptor antagonist and inverse agonist, to improve both cardiac symptoms and ventricular remodeling associated with CHF [98]. Cardiac manifestation of hyper-eosinophilia is referred to as EM. These observations point towards the importance of activated mast cells and the associated release of histamine in subsets of heart disease. Note that both eosinophils [15] and mast cells can improve cardiac function after myocardial infarctions. Antihistamine treatments and mast cell stabilizers may provide benefits to some types of eosinophilias associated with cardiac manifestations.

Kimura’s disease is a benign, rare, chronic inflammatory disorder of uncertain etiology associated with peripheral blood eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels [8]. In a study of 23 cases, recruitment of IgG4+ plasma cells was a common feature [99]. While the exact cause of Kimura disease is unknown, it may be triggered by an allergic reaction or infection. Treatment for Kimura’s disease typically involves surgical excision for localized lesions (preferred initial treatment), systemic immunosuppressants, and, in some cases, radiation therapy. Lesions may recur over time post-surgical excision [100].

The importance of mast cells in some eosinophilic diseases may be under appreciated. Eosinophils and mast cells play multiple roles in the innate immunologic host defense. Overstimulation of mast cells and eosinophils in response to high levels of IgE, antigens, cytokines, and/or other stimulations can result in asthma, allergies, eosinophilias, and other disease conditions. Crosstalk between eosinophils and mast cells can evolve into a persistent disease state, with mast cell/eosinophil paired couplets observed in some instances. Hyperactivation of mast cells results in locally elevated histamine and inflammatory molecules, resulting in rashes, pruritus, urticaria, and sometimes vasoconstriction.

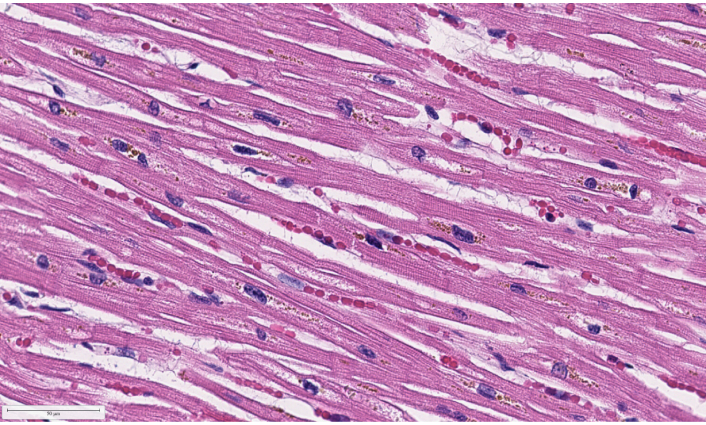

Hypothesis: Vasoconstriction induced by elevated histamine levels may occur from contracted pericyte cells [32, 101, 102]; we propose that mast cell-induced vasoconstriction may play an important role in several forms of heart disease [32, 103] (Figure 2).

NIH COVID-19 Digital Pathology Repository putative COVID-19 patient heart H&E tissue autopsy 73, image 1,560 (40×) of capillary with red blood cells [104]. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin staining; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

Antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers have been observed to provide therapeutic benefits for a subset of the disease conditions reviewed herein. These treatments may provide additional benefits as an adjunctive therapy to enhance existing eosinophilia treatment protocols. Targeting mast cells in allergic diseases has been previously proposed by Burchett et al. [105]. Efficacy results are likely to be dose sensitive, with higher doses needed to target mast cells in tissues away from the gastrointestinal system [106].

Mast cells and eosinophils interact in a variety of disorders. For a subset of these disorders, the role of mast cells and mast cell interactions with eosinophils may not be fully appreciated. Mast cells play an important role in some allergies, eosinophilic diseases, and asthma; therapeutics targeting mast cells, IL-5, and IL-5R can be evaluated in cases where steroids are contraindicated or current treatments are insufficient. Antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, anti-IL-5, and anti-IL-5R may provide additional therapeutic benefit to patients suffering from certain allergic and eosinophilia diseases with candidate adjunctive treatments to be evaluated in clinical studies.

AD: atopic dermatitis

CAS: coronary artery spasm

CHF: chronic heart failure

DRESS: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

EC: eosinophilic colitis

EE: eosinophilic enteritis

EG: eosinophilic gastritis

EGE: eosinophilic gastroenteritis

EGIDs: eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders

EGPA: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

EM: eosinophilic myocarditis

EoE: eosinophilic esophagitis

EP: eosinophilic eosinophilic pancreatitis

Fc: fragment crystallizable

FGIDs: functional gastrointestinal disorders

HES: hypereosinophilic syndrome

IBS: irritable bowel syndrome

IgE: immunoglobulin E

IgG: immunoglobulin G

IL: interleukin

KS: Kounis syndrome

MCAS: mast cell activation syndrome

RA: rheumatoid arthritis

SMCD-eos: systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia

Th2: T helper cell 2

The author acknowledges Dr. Nicole Gherlone and Dr. Maurice Fremont-Smith for useful conversations.

DOR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author has read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Tanmay Singhal ... Vikrant Rai