Affiliation:

College of Life Sciences, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453007, Henan Province, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6032-6896

Affiliation:

College of Life Sciences, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453007, Henan Province, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-2355-3205

Affiliation:

College of Life Sciences, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453007, Henan Province, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3304-7610

Affiliation:

College of Life Sciences, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453007, Henan Province, China

Email: 041125@htu.edu.cn

Explor Dig Dis. 2025;4:1005106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2025.1005106

Received: October 13, 2025 Accepted: December 03, 2025 Published: December 09, 2025

Academic Editor: Jose Carlos Fernandez-Checa, Institute of Biomedical Research August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Spain

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors, ranking fifth in incidence and third in mortality worldwide. China also bears a high burden of GC, second only to lung cancer. With the advancement of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology, the mechanisms underlying the development and progression of various tumor types have been elucidated. This article summarizes the application of CRISPR technology in the functional genomics identification and target screening of GC genes, explores the use of chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy for solid gastric tumors, and discusses the progress and significance of CRISPR technology in constructing GC models using organoids.

Gastric cancer (GC) represents a major global health burden, consistently ranked as the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality. The pathogenesis of GC is multifactorial, driven by an accumulation of genetic alterations and intricate regulation within the tumor microenvironment (TME). The term typically refers to adenocarcinoma, a malignancy arising from the gastric mucosal epithelium, which constitutes the majority of gastric carcinomas. Other, less common malignant tumors affecting the stomach include gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), gastric lymphoma, and gastric neuroendocrine tumors [1]. Therefore, seeking an efficient and precise treatment approach is essential. As a revolutionary gene-editing tool, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology has provided powerful tools for constructing precise GC models. It is widely applicable in discovering novel therapeutic targets, building GC models, investigating drug resistance mechanisms, and optimizing immunotherapy. CRISPR technology can target GC-related genes through gene editing, enhance the anti-tumor activity of immune cells, and be combined with nanocarriers for GC treatment. However, current research on CRISPR genome editing for establishing GC models still lags behind that of other high-incidence cancers (e.g., lung cancer, colorectal cancer). This review interrogates the literature indexed on PubMed over the past six years (2020–2025) using the keywords “CRISPR” and “gastric cancer”. The analysis reveals a substantial body of research in both the fields of GC biology and CRISPR-Cas technology. However, despite CRISPR’s well-established potential as a versatile gene-editing tool, its direct application in developing novel therapeutic strategies for GC remains relatively unexplored. This review synthesizes the current landscape of CRISPR-based research in GC and delineates future translational prospects for its clinical application.

The CRISPR system has demonstrated significant potential in GC treatment. Domestic and international studies have extensively utilized CRISPR technology to simulate key gene mutations in GC. Through CRISPR screening, genes such as methyltransferase-like (METTL), OTUD5, and HNRNPA2B1 have been identified as potential therapeutic targets for GC [2–4]. To validate the role of the METTL gene, the authors interrogated a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout library (TKOv3) in GC cells. This screen identified 184 novel essential genes. Subsequent knockdown of key candidates—including SPC25, DHX37, ABCE1, SNRPB, TOP3A, RUVBL1, CIT, TACC3, and MTBP—significantly impaired cell viability and proliferation. Furthermore, temporal analysis of essential genes revealed that prolonged selection pressure enriches for a distinct set of genetic dependencies.

Following progressive selection, 41 essential genes were progressively identified as potential drug targets. Among these, METTL1 was overexpressed in GC tissues. In 3 out of 6 GC cohorts, METTL1 overexpression correlated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo downregulation of METTL1 significantly inhibited GC cell growth. Functional analysis indicated METTL1 may act in the cell cycle via the AKT/STAT3 pathway, validating METTL1 as a potential therapeutic target for GC [2]. GPX4, a glutathione peroxidase, is a key negative regulator of ferroptosis. It is highly expressed in GC and contributes to promoting tumor growth. In the current study, targeting GPX4 regulation has emerged as a strategy for inducing ferroptosis and developing effective GC therapies. Researchers employed CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out the OTUD5 gene in the GC cell line MFC and investigated its effects in a subcutaneous tumor model. CRISPR functional genomics studies reveal a novel context-dependent mechanism of the deubiquitinating enzyme OTUD5 in GC. Different from its traditional tumor-suppressing role, OTUD5 expression is suppressed in the context of p53 activation. This suppression prevents OTUD5 from stabilizing GPX4, a key inhibitor of ferroptosis, leading to GPX4 degradation and inducing ferroptosis in GC cells. This discovery not only establishes a direct molecular bridge between p53 signaling and ferroptosis but also provides a novel therapeutic strategy for treating p53 wild-type GC [3]. Moreover, CRISPR technology has been employed to construct mouse models of GC, revealing that Apc gene knockout can induce gastric lesions resembling human pyloric gland adenomas, thereby providing tools for mechanistic research [5] (Table 1).

Representative CRISPR-based studies in GC.

| Target/Area | Function/Pathway | CRISPR tool | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METTL1 | tRNA methylation & translation | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout/screening | A novel dependency gene promotes GC proliferation and metastasis. | [2] |

| OTUD5 | Deubiquitination & ferroptosis | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout | p53 suppresses OTUD5, promoting GPX4 degradation and ferroptosis. | [3] |

| HNRNPA2B1 | RNA splicing & chemoresistance | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout | Knockout overcomes chemoresistance in GC stem cells. | [4] |

CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; GC: gastric cancer; METTL1: methyltransferase-like 1.

By employing CRISPR-Cas9 screening, Table 1 compares the roles of three genes—METTL1, OTUD5, and HNRNPA2B1—in GC. The findings highlight that each gene promotes GC progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance through distinct mechanisms: translational regulation, ferroptosis, and RNA splicing. Collectively, these results underscore the promise of these targets for advancing mechanistic understanding and therapeutic development in GC [2–4].

Since its emergence, the CRISPR-Cas system has revolutionized the field of genetic engineering. Genome editing technology involves the precise modification of DNA sequences within organisms through artificial means and is widely used in gene function research, synthetic biology, and other areas. The most renowned gene editing technology is the CRISPR-Cas system, representing the third generation of gene editing tools following zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN) [6, 7]. It is an adaptive immune system derived from prokaryotic CRISPR, utilized to defend against viral (phage) or foreign genetic material (e.g., DNA) invasion [8, 9]. A typical CRISPR-Cas system consists of a leader sequence, repeat units, spacer units, a CRISPR array (storage site) synthesized by tracrRNA, and a Cas gene locus. The CRISPR locus exhibits high diversity and variable spacer sequences [10]. As the most advanced gene editing technology, CRISPR-Cas can edit almost any DNA location, store foreign genomes as spacer sequences, and insert them into the CRISPR array. It has redefined the concept of genetic model animals, implying that all animals (including humans) can serve as animal models [7].

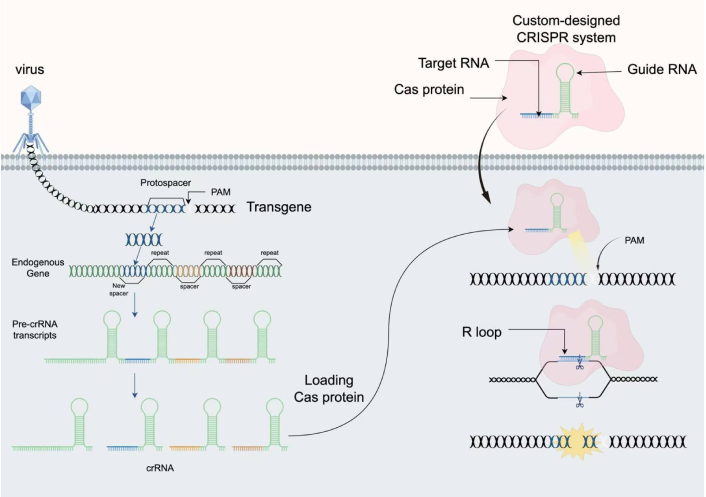

The CRISPR-Cas system can be divided into two major classes based on the Cas effector proteins: one type comprises a complex of multiple effector proteins [11], while the other relies on a single effector protein [12, 13] (Table 2). The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas typically involves three stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. In the adaptation stage, the Cas complex binds to invading DNA molecules via a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), causing double-strand breaks in the invading DNA and releasing short DNA fragments (protospacers) of approximately 20–30 bp. These fragments are integrated into the CRISPR array between two repeat sequences through transesterification, completing the insertion of the foreign gene fragment (Figure 1). In the expression stage, the CRISPR array is transcribed into precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA), which is processed by Cas proteins and cofactors into short, mature crRNAs, finalizing the processing and modification of the invading gene fragment. In the interference stage, through the combined action of crRNA and Cas proteins, crRNA acts as a guide to specifically target and recognize invading DNA, activating cleavage and mediating the degradation of foreign nucleic acids to protect the host from infection [14–17].

Fundamental classification of CRISPR types.

| Class | Effector complexity | Type | Representative effector | Target | Key characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Multi-subunit complex | I | Cas3 | DNA | Multiprotein complex, separate cleavage unit |

| III | Cas10 | RNA/DNA | Targets RNA, induces a broad immune response | ||

| IV | Csf | Incomplete system, diverse functions | |||

| Class 2 | Single effector protein | II | Cas9 | DNA | Most widely used, requires tracrRNA |

| V | Cas12 | DNA | No tracrRNA needed, cis-cleavage activity | ||

| VI | Cas13 | RNA | Targets RNA, trans-cleavage activity |

CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats.

CRISPR-based adaptive immunity provides programmable genome editing tools. PAM: protospacer adjacent motif; CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; crRNA: CRISPR RNA. CRISPR immune systems target DNA or RNA in microbes (illustration depicts DNA targeting). Three steps to immunity include: acquisition of CRISPR spacer sequence matching an infectious agent; transcription and formation of Cas-RNA complexes; and seek-and-destroy surveillance mechanisms. CRISPR-Cas9 is the canonical genome editing tool for RNA-guided genetic manipulation. Cas9 searches for target sites in a genome by engaging with PAM sequences, forming an R-loop with complementary DNA, generating a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) break, and finally releasing DNA for repair. The figure was created by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

CRISPR technology has achieved significant breakthroughs in the treatment of monogenic genetic disorders, cancer immunotherapy, genetic engineering of human stem cells and organoids, and other fields, demonstrating immense potential in biomedical research and clinical applications. In GC, CRISPR technology is widely used as a precise and efficient tool, driving the development of next-generation precision medicine.

The field of gene therapy has progressed remarkably in the 21st century. A key breakthrough has been the development of CRISPR technology, which holds immense promise for the precise treatment of inherited genetic disorders. Notable examples where significant progress has been made include β-thalassemia, sickle cell anemia, and Huntington’s disease. The work of Smithies et al. [18], Thomas and Capecchi [19], and Evans et al. [20], who successfully achieved gene targeting in mice using gene editing technology, represents a milestone in disease gene therapy research.

With the advent and progress of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, precise genome editing has yielded encouraging results in basic and clinical research for treating various genetic diseases, including β-thalassemia [21]. Altering the target of CRISPR/Cas9 merely requires changing the guide RNA sequence, enabling the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system to serve as a tool for modifying genetic material in diverse cell types and organisms [22]. The CRISPR/Cas9 system can design specific gRNAs to directly target and knock out oncogenes that are abnormally highly expressed in GC, thereby inhibiting the malignant phenotype of tumor cells. CRISPR technology can target multiple key molecules in GC, such as human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) and GRIN2D. For HER2-amplified GC, CRISPR technology is not only employed to validate the necessity of HER2 as a therapeutic target but also utilized to investigate its resistance mechanisms, such as identifying key genes involved in the activation of downstream signaling pathway bypasses through screening. In a study by Su et al. [23], CRISPR-Cas9 technology was used to knock out the PD-1 gene on human T cells to investigate whether the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway affects the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy in Epstein-Barr virus-associated GC (EBVaGC). The results indicated that the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway indeed contributes to immune tolerance in EB-associated GC. T cells with blocked PD-1 expression demonstrated more significant anti-tumor effects compared to the control group [23]. The application of CRISPR technology in GC has evolved from functional genomics to a promising therapeutic strategy. A significant advancement lies in its combination with nanocarriers, forming a platform for precise in vivo gene editing and synergistic therapy, thereby enhancing treatment efficacy and specificity. Current research trends are shifting from single-gene editing to synergistic mutations of multiple genes, presenting a multi-dimensional, precise, and personalized development direction focused on precise targeting, immunotherapy, and the exploration of novel biomarkers.

CRISPR library technology is widely employed in GC target research, owing to its ready adaptability to mammalian cells, with lentiviral transduction serving as a standard delivery modality. This discovery has positioned CRISPR as a novel screening technology. Targeting information is encapsulated within a short nucleotide sequence, which can be easily produced on a large scale using oligonucleotide synthesis technology. This enables the rapid assembly of a comprehensive library of genetic perturbations (e.g., knockout, activation), which is subsequently packaged into retroviral vectors using standard cloning methodologies, making it suitable for high-throughput functional genomics screens. This library is then delivered en masse into a large cell population, ensuring each cell receives only one perturbation tool, thus forming a “perturbation library” across the entire cell population. The cells are subsequently subjected to selective pressure, forcing them to compete for survival under specific conditions (e.g., drug treatment, nutrient deprivation). High-throughput sequencing technology can compare the abundance changes of different perturbation tools before and after screening to identify which gene perturbations affect cellular survival advantages or disadvantages under specific pressures, thereby pinpointing the target genes. CRISPR screening is currently the most mainstream technology. It involves using the CRISPR-Cas9 system to construct a mixed gRNA library to infect cells. By controlling infection conditions, each cell is infected by only one viral particle, integrating only one gRNA, thereby targeting one gene. Relevant genes are screened through various methods, and the enrichment fold of each gRNA is calculated to analyze abundance changes, thus identifying the most critical target genes [24]. Gene screening for GC is a crucial direction in current precision medicine research. A growing number of researchers have identified related targets. Rezaei et al. [25] found that the expression levels of ITGAX, CCL14, ADHFE1, and HOXB13 were significantly higher in GC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues.

Utilizing CRISPR technology, researchers have discovered an increasing number of novel research targets. METTL1 has been validated as a potential therapeutic target for GC [2]. Zeng et al. [2] identified the RNA methyltransferase METTL1 as a potential therapeutic target for GC through a genome-wide CRISPR screening. Mechanistically, METTL1 promotes GC proliferation by catalyzing m7G modification of tRNA, which in turn enhances the translation of oncogenic mRNAs. This finding provides the first evidence directly linking tRNA modifications to gastric tumorigenesis, revealing novel therapeutic avenues independent of classical signaling pathways [2]. Similarly, Zhang et al. [3] found that the deubiquitinating enzyme OTUD5 is suppressed by p53, and its deletion induces ferroptosis in GC cells by promoting GPX4 protein degradation, linking p53 regulation to a novel mechanism of cell death. Yu et al. [4] demonstrated that HNRNP A2B1 plays a pivotal role in maintaining chemotherapy resistance in GC stem cells by regulating a series of transcripts associated with stemness and DNA damage repair. Systems biology approaches suggest that these genes may serve as potential marker genes for GC, providing insights for future experimental studies. Although chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) therapy has multiple potential targets in GC, the search for new and superior biomarkers continues [26].

In current research, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems based on dCas9 achieve precise, reversible regulation of transcriptional activity at specific gene loci by fusing catalytically inactivated Cas9 proteins with transcription repressors (such as KRAB domains) or co-activator complexes (such as the SAM system), respectively. These systems transcend the scope of traditional gene editing, serving as powerful functional genomics platforms widely applied in genome-wide loss-of-function and gain-of-function screening. By precisely reducing gene expression, they enable accurate regulation of gene transcription, providing unprecedented tools for deciphering the complex epigenetic regulation, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion mechanisms in GC [27].

m6A is the most abundant mRNA modification, catalyzed by the methyltransferase complex, and its expression is highly dependent on cellular context and target genes. Functional gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies using CRISPRi/a can reveal its complex bidirectional regulatory network. Wang et al.’s [28] research indicates that in GC, P300-mediated histone modifications promote METTL3 transcription, which stimulates m6A modification of HDGF mRNA. Subsequently, this m6A modification enhances the stability of HDGF mRNA. Secreted HDGF promotes tumor angiogenesis and increases glycolysis in GC cells, which correlates with subsequent tumor growth and liver metastasis [28]. METTL3 loss exerts tumor-suppressing effects by stabilizing tumor suppressor genes while simultaneously inhibiting oncogenic transcripts. This context-dependent mechanism explains the complexity of m6A-targeted therapies and provides a molecular basis for patient stratification.

Under simulated TME conditions, genome-wide CRISPRi screening revealed that multiple transcription factor (TF)-mediated direct and indirect mechanisms are associated with the transcription of PYCR1, a key enzyme in proline synthesis. This study identifies PYCR1 as a metabolic vulnerability in GC cells. Activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway promotes 4E-BP1 inactivation, inducing the release of TF eIF4E and ultimately triggering c-MYC transcription [29]. In GC, activation of the PI3K/AKT/c-MYC axis was identified as the primary mechanism for PYCR1 upregulation. PIK3CA mutations and c-MYC amplification showed positive correlations with PYCR1 upregulation, revealing cross-regulation between metabolic interventions and cell death pathways [30].

Beyond the classic interferon-γ signaling pathway, CRISPRi identifies “non-classical” upstream regulatory pathways governing PD-L1 expression in cancer cells.

Screening identified novel non-classical regulatory factors, including CMTM6 and PTPN2 [31]. Manguso et al. [32] employed an in vivo gene screening approach combined with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to identify previously undescribed immunotherapy targets in transplanted tumors of mice undergoing immunotherapy. They validated that deletion of the tumor cell tyrosine phosphatase PTPN2 enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy by amplifying the effects of interferon-gamma on antigen presentation and growth inhibition [32]. These studies confirm that CRISPRi technology can reveal gene functional networks that are difficult to detect using traditional methods, providing a deep mechanistic basis for developing precision treatment strategies for GC.

CRISPR-Cas technology, renowned for its precision and efficiency, is widely used in studying tumor-related gene functions, establishing tumor-bearing animal models, and exploring drug targets. Through CRISPR technology, researchers can optimize the efficacy of CAR-T cells. CAR-T cell therapy is currently the fastest-growing and most widely applied branch of tumor cellular immunotherapy [33]. CRISPR/Cas9-edited CAR-T cells can target previously untreatable cancer types, offering new hope for patients with refractory cancers [34].

Over the past decade, research on the CRISPR-Cas system has evolved from a newly discovered bacterial defense mechanism into a diverse set of genetic tools applied across all fields of life science. CRISPR technology enables us to directly edit the genes of immune cells, such as T cells, thereby disrupting the immune balance that hinders disease treatment and enhancing or suppressing immune responses. For example, research by Ohaegbulam et al. [35] revealed that PD-1/PD-L1 maintains high expression on the surface of various malignant tumors. PD-L1 binds to inhibitory receptors on T cells, leading to T cell dysfunction and enabling tumors to evade immune surveillance [35]. Compared to anti-PD-1 antibody drugs (such as Keytruda and Opdivo), gene knockout fundamentally blocks PD-1 protein expression, potentially offering more durable effects and avoiding certain side effects associated with antibody therapies. Stadtmauer et al. [36] published one of the first clinical trial reports on CRISPR-edited T cells (targeting PD-1 and others). By removing the gene encoding programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1; PDCD1), they successfully enhanced anti-tumor immunity, demonstrating its safety and feasibility in humans [36]. Giuffrida et al. [37] demonstrated that a clinically relevant CRISPR/Cas9 strategy targeting A2AR significantly enhanced its in vivo efficacy using mouse and CAR-T cells, thereby improving mouse survival rates. Mechanistically, targeting A2AR using the CRISPR/Cas9 approach significantly enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of CAR-T cells in both mice and humans, outperforming shRNA-mediated knockdown or pharmacological A2AR blockade [37]. Multiple global clinical trials have been conducted using CRISPR-edited PD-1 knockout T cells to treat advanced solid tumors such as lung cancer and liver cancer, demonstrating favorable safety profiles and preliminary efficacy.

Since Eshhar et al. [38] first proposed the CAR concept in 1993 and demonstrated that the single-chain variable fragment (scFv)-CD3ζ structure can activate T cells—foundational work for the first-generation CAR—followed by Finney et al. [39] first proving that CD28 costimulation significantly enhances CAR-T activity, spurring the development of the second-generation CAR, and further advanced by Davenport et al. [40] and Xiong et al. [41] through their studies on CAR-T killing mechanisms and immune synapse formation, CAR-T cell technology has continuously evolved.

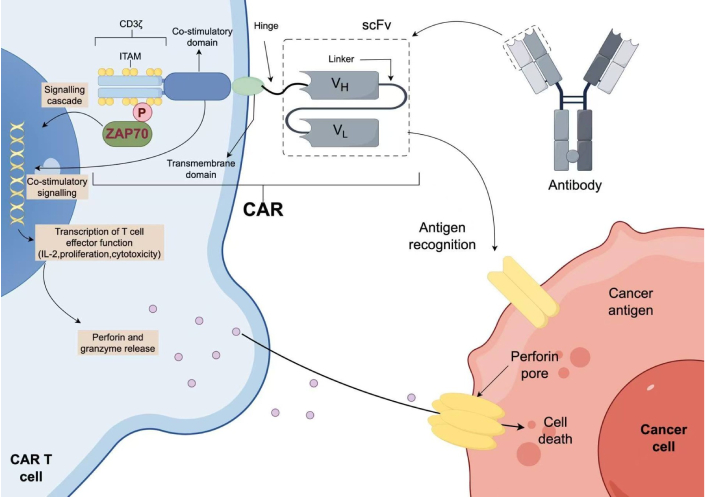

Following FDA approval of Kymriah and Yescarta (CD19-directed CAR-T cells for B-cell leukemia and lymphoma), CAR-T cell therapy has revolutionized cancer treatment [42]. CAR-T technology is a revolutionary immune cell therapy that involves genetically engineering a patient’s own T cells to specifically recognize and kill cancer cells (Figure 2). First-generation CAR molecules consist of a scFv derived from monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize antigens, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain from CD3 [43]. Second-generation CARs incorporated costimulatory domains such as CD28 or 4-1BB to enhance and prolong CAR-T cell activation. Third-generation CARs integrated two of the domains from CD28, 4-1BB, and OX40, substantially boosting the anti-tumor capability of CAR-T cells [44–47]. CAR-T cells have now progressed to the fourth generation, further modified from the second and third generations by integrating additional functional components to overcome TME suppression and improve efficacy.

Schematic of a basic second-generation CAR-T cell. IL-2: interleukin 2. The extracellular portion of the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) molecule is typically generated from a monoclonal antibody against the target. The variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains, also known as the single-chain variable fragment (scFv), from the antibody sequence are connected by a linker to form the antigen-specific region of the CAR molecule. The hinge or spacer region anchors the scFv to the transmembrane region that traverses the cell membrane. Intracellularly, the co-stimulatory domain and CD3ζ chain signal once the scFv portion of the CAR recognizes and binds tumour antigen. Co-stimulatory signals are dependent on the co-stimulation domain used: CD28 is dependent on PI3K, whereas 4-1BB requires tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). The CD3ζ chain contains three immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) domains that, upon phosphorylation (P), signal through ζ-associated protein of 70 kDa (ZAP70). Downstream signalling leads to T cell effector functions, including the release of perforin and granzyme, leading to cell death of the target tumour cell. The figure was created by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

CRISPR-Cas9 technology provides a powerful tool for the precise genetic engineering of next-generation CAR-T cells, significantly enhancing their antitumor efficacy and persistence. Its potential for clinical translation has been validated in multiple trials. The key to CAR-T therapy for GC lies in selecting tumor antigens that are highly specific, widely expressed, and associated with prognosis. Knocking out the PD-1 gene in T cells effectively reverses TME-induced T cell exhaustion. Preliminary clinical results demonstrate its favorable safety profile and encouraging antitumor activity in the treatment of solid tumors [36].

Currently, the most focused-upon targets are CLDN18.2 (Claudin 18.2) and the significant target HER2. Some studies have targeted both simultaneously, showing not only effective inhibition of GC growth but also a significant reduction in off-target risks.

In clinical trials, Qi et al. [48] employed CT041 CAR-T-cell therapy to treat Claudin18.2-positive metastatic cancer of the pancreas, achieving favorable outcomes in both cases. Compared to persistent cytokine responses, peripheral immune alterations proved more enduring, involving phenotypic changes across multiple immune cell types. Significant disease remission was also observed, demonstrating the feasibility of this strategy in addressing the challenges of solid tumors [48]. Research by Fleuranvil et al. [49] examined the anti-tumor function of a bispecific Claudin18.2/TGFβ-targeting CAR-T cell candidate in a preclinical orthotopic mouse model of GC with an immune-competent background and in GC patient-derived organoids (PDOs) within an immunodeficient orthotopic mouse model. It confirmed that the bispecific Claudin18.2/TGFβ CAR-T cell candidate could be an effective treatment for gastric tumors expressing Claudin 18.2 [49]. The Claudin18.2-targeting CAR-T product CT041 has entered the world’s first confirmatory Phase II clinical trial.

During the research of Shi et al. [50], it was confirmed that interleukin 15 (IL-15) modification enhanced the anti-tumor activity of CLDN18.2-targeting CAR-modified T (CAR-T) cells in immunocompetent mouse tumor models. A growing body of research confirms the importance of Claudin18.2 in GC treatment [50], establishing CAR-T cell therapy as an effective treatment modality. Several global CAR-T projects have entered Phase III clinical trials, indicating the technology’s application has reached a critical stage.

CAR-T cell therapy is an immunotherapy that involves genetically engineering a patient’s own T cells to express CAR molecules that specifically recognize tumor surface antigens. The modified T cells are then infused back into the patient to kill tumor cells or autoimmune cells. The core structure of CAR-T cells is the CAR, which includes: an extracellular antigen-binding domain, a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain. The CAR is a genetically engineered receptor that couples an anti-CD19 single-chain Fv domain to the intracellular T-cell signaling domain of the T-cell receptor, thereby redirecting cytotoxic T lymphocytes to cells expressing that antigen. Using lentiviral vector technology for gene transfer and permanent T-cell modification, CTL019 (formerly known as CART19) engineered T cells express a CAR where T-cell activation signals are provided by the CD3ζ domain, and costimulatory signals are provided by the CD137 (4-1BB) domain. The detailed mechanism of action of CAR-T cells can be divided into T-cell activation and tumor recognition, tumor killing mechanisms, and the formation of immune memory. In the T-cell activation and tumor recognition stage, after the CAR’s scFv binds to the tumor surface antigen (e.g., CD19), an immune synapse forms. The CAR-T cell establishes close contact with the target cell and recruits signaling molecules, thereby activating the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) and triggering downstream pathways, promoting T-cell proliferation. In the tumor killing mechanism, CAR-T cells release perforin to perforate the tumor cell membrane and inject granzyme B to induce apoptosis. CAR-T cells express FasL, which binds to the Fas receptor on tumor cells, activating a cascade reaction that leads to cytokine-mediated killing. In the third stage, some CAR-T cells differentiate into central memory T cells or stem cell-like memory cells, providing long-term protection to the body [51–58]. However, the clinical implementation of this technology still faces two major core challenges. The primary challenge lies in optimizing the delivery system. Currently, the primary approach relies on viral vectors (such as lentivirus LV and adeno-associated virus AAV), which enable highly efficient editing but are subject to packaging capacity limitations, potential insertion mutation risks, and high production costs. Non-viral systems (such as electroporation-mediated delivery of CRISPR RNP) have garnered attention for their superior safety profile and lower cost advantages. However, their editing efficiency and cell survival rates in primary T cells still require further improvement [59]. Therefore, the selection of delivery systems requires careful balancing between efficacy and safety. Another key challenge is the potential immunotoxicity associated with CRISPR editing. On one hand, knockout of immune checkpoints (such as PD-1) may enhance T-cell function while also potentially triggering excessive immune responses, leading to “on-target, off-tumor” toxicity or cytokine release syndrome (CRS) [60]. On the other hand, off-target effects inherent to the CRISPR system may disrupt normal gene function and pose unforeseen autoimmune risks. Therefore, developing high-fidelity Cas9 variants and conducting rigorous off-target assessments are indispensable steps for future clinical applications [61].

Although CAR-T therapy has made significant progress in treating hematological malignancies, it still faces considerable challenges in solid tumors. Even with an optimal killing function, CAR-T cells must overcome obstacles posed by the TME [62]. Under current research, investigators are deeply analyzing the resistance mechanisms of CAR-T cells in solid tumors, such as altering tumor surface antigen expression or establishing an immunosuppressive microenvironment to evade CAR-T cell attack. For instance, Labanieh et al. [63] developed SUPRA CAR to remotely control CAR-T cell activation and CART. BiTE aims to prevent off-tumor toxicity and antigen escape [63]. Current research is focusing on co-culturing patient-derived GC organoids with autologous or engineered CAR-T cells to simulate in vivo anti-tumor responses, screen efficient targets, and predict clinical efficacy.

Using CRISPR screening, genes critical for organoid initiation, proliferation, and survival can be identified, thereby optimizing the required growth factors and signaling pathway inhibitors for culture conditions. In previous studies, knocking out PD-1 released the functional inhibition of T cells, restoring their ability to kill tumor cells. In animal models, PD-1 knockout T cells also demonstrated enhanced tumor infiltration and clearance capabilities. Furthermore, Giuffrida et al. [37] have shown that targeting the adenosine A2A receptor using a clinically relevant CRISPR/Cas strategy can significantly increase the number of infiltrating CAR-T cells and their capacity to inhibit tumor growth. CAR-T therapy targeting CLDN18.2 has entered clinical trials and has shown promising efficacy.

The combination of CRISPR technology and organoids represents another emerging field in biomedical research. Organoids are cultivated from stem cells (including induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells, etc.) and can self-assemble in vitro to simulate the development and function of real organs. Consequently, organoids can be widely used in biological mechanism studies and drug screening [64]. Currently, CRISPR technology has been utilized to create tumor organoid models for investigating tumorigenesis and development mechanisms. The core advantage of organoid technology lies in its ability to mimic cellular interactions within the TME. CRISPR technology enables precise knockout or insertion of target genes, thereby generating ideal tumor models, particularly in breast cancer and colorectal cancer [65]. Lo et al. [66] established the first human forward genetics model of the common tumor suppressor gene ARID1A—a human GC ARID1A-deficient organoid model—revealing essential and non-essential pathways in carcinogenic transformation. In this model, researchers employed and integrated multiple technologies—including CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, organic culture, systems biology, and small molecule screening—to reveal both essential and non-essential pathways of carcinogenic transformation in a human GC ARID1A-deficient organoid model [66]. Nanki et al. [67] established the first large-scale biobank of GC organoids and systematically employed CRISPR/Cas9 for gene editing (such as ARID1A knockout) in these organoids to investigate carcinogenic mechanisms.

Researchers have established PDOs from GC patients. These organoids retain the histological characteristics of their corresponding primary GC tissues. The responses of GC organoids to different chemotherapy drugs, assessed via RNA sequencing, were consistent with responses in mouse models based on PDOs. Evaluating the chemotherapy sensitivity of PDOs can serve as a valuable tool for screening chemotherapy drugs for GC patients [68]. The integration of CRISPR technology with GC organoid models significantly enhances our capability to conduct functional genomic studies in a context closely resembling the patient’s actual situation (Table 3).

Integrated strategy for developing next-generation CAR-T therapies using CRISPR and organoid platforms.

| Technology platform | Core input | Process & methodology | Key output | Contribution to CAR-T therapy development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR screening | Patient-derived gastric cancer organoids, genome-wide sgRNA library. | Genome-wide CRISPR knockout screening in organoids, followed by NGS analysis of enriched/depleted sgRNAs. | 1. Validated novel therapeutic targets (e.g., membrane protein X).2. Potential targets for overcoming resistance. | Provides a target blueprint: Enables systematic, unbiased discovery of ideal new targets for CAR design, providing source innovation. |

| Organoid modeling & co-culture | 1. Novel targets from screening.2. Candidate CAR-T cells. | 1. Generation of organoids expressing the novel target.2. In vitro co-culture with candidate CAR-T cells.3. Real-time imaging, cytotoxicity assays, cytokine profiling. | 1. Quantitative cytotoxicity data of CAR-T cells.2. Assessment of tumor specificity (on-target activity).3. Early warning of “on-target, off-tumor” toxicity risk. | Provides a predictive preclinical platform: High-throughput validation of candidate CAR-T efficacy and safety in a system that closely mimics the human TME, significantly de-risking clinical translation. |

| CRISPR engineering of CAR-T | 1. Validated functional targets.2. Patient T cells. | 1. Vector delivery: Introduction of CAR genes targeting novel antigens.2. Gene editing: Knockout of immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1, A2AR) to enhance function. | 1. CAR-T cells targeting novel antigens.2. Functionally enhanced (e.g., anti-exhaustion) CAR-T cells.3. Multi-optimized “off-the-shelf” CAR-T candidate products. | Provides an optimized “living drug”: Translates upstream discoveries into potent weapons against solid tumors. Generates more potent and persistent CAR-T products via multiplexed gene editing. |

CAR-T: chimeric antigen receptor T; CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; TME: tumor microenvironment.

As a major breakthrough in modern biology and medicine, CRISPR technology holds great potential across multiple fields but still faces numerous challenges. These include optimization of delivery mechanisms and the issue of off-target effects. Developing safe and effective in vivo delivery remains the foremost challenge for the widespread clinical application of CRISPR/Cas9 in human therapeutics. Most current clinical studies employ viral vectors, yet challenges such as immunogenicity, cytotoxicity, and carcinogenicity still need to be overcome [69].

Regarding delivery, there are currently three methods to deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 complex into cells: physical, chemical, and viral vectors. Non-viral delivery methods include electroporation, microinjection, and hydrodynamic injection. Electroporation technology applies a strong electric field to the cell membrane to temporarily increase its permeability, with the main limitation being significant cell death [70]. Microinjection involves directly injecting the CRISPR/Cas9 complex into cells at a microscopic level to rapidly edit individual cells. However, this method is technically challenging, prone to causing cell damage, and only applicable to a limited number of cells [71]. Viral vectors are natural experts for in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 delivery [72]. Owing to their higher delivery efficiency compared to physical and chemical methods, viral vectors are currently widely used as delivery methods. Retroviral and lentiviral transfection utilize the infection mechanism of viruses to stably integrate foreign gene sequences, allowing for stable expression of the target gene. Viral vectors typically exhibit high delivery efficiency, effectively introducing CRISPR/Cas9 components into recipient cells. Viral vectors include adenoviruses, etc. Their advantage lies in the ability to infect a wide variety of cell types, while their disadvantages include poor targeting specificity, tendency to elicit immune responses, and difficulties in clinical application [73, 74].

Future development of viral vectors: Research on delivery systems utilizing encapsulation with lipid nanoparticles (LNP) or polymeric carriers will focus on the following directions through optimization: Novel non-component and surface modifications (such as ligand targeting) enable tissue-specific delivery and reduce immune responses. Engineering of viral vectors: Modifying AAV through capsid engineering to enhance targeting specificity and reduce immunogenicity, while exploring novel viral vectors with increased packaging capacity. Optimization of instant delivery strategies: Direct delivery of pre-assembled CRISPR ribonucleoprotein complexes, due to their short intracellular residence time, significantly reduces off-target effects and immunogenicity, making it a key future development direction.

Concerning off-target effects, these refer to the phenomenon where the CRISPR system edits non-specific DNA sites outside the intended target gene. This unintended editing can disrupt other genes or regions, leading to adverse consequences such as mutations or unintended alterations in gene function [75]. In GC research, given the involvement of multiple aberrantly activated signaling pathways, off-target events could interfere with key regulatory genes or even induce new carcinogenesis. Current research is attempting to enhance specificity and reduce off-target effects by optimizing sgRNA design or by engineering Cas enzymes to possess higher specificity, hoping to achieve better outcomes in mitigating off-target effects.

Future security enhancement strategies will focus on the application of high-fidelity CAS variants: computational biology and sgRNA optimization: designing sgRNAs with minimal off-target potential using advanced algorithms, combined with chemical modifications to enhance stability and specificity. Exploring novel editing systems: base editing and guide editing systems enable precise editing without causing DNA double-strand breaks, fundamentally avoiding off-target issues triggered by such breaks and offering superior safety advantages. In summary, through a dual-track strategy of innovating delivery systems and enhancing editing precision, CRISPR technology holds promise to overcome existing bottlenecks and realize its full potential in disease treatment at an early stage.

All currently approved CRISPR clinical studies are strictly limited to somatic cell editing (such as modifying T cells or tumor cells) [76], where genetic alterations are confined to the individual and do not pass to subsequent generations. This approach is widely accepted as ethically sound. However, germline editing—the heritable modification of sperm, eggs, or early embryos—has raised the most profound ethical concerns within the international scientific community due to its potential to permanently alter the human gene pool and possibly lead to unforeseeable long-term consequences [77]. The 2018 He Jiankui incident serves as a stark warning. Consequently, the vast majority of countries and scientific organizations worldwide have imposed strict bans or moratoriums on such practices, emphasizing that any clinical application of germline editing remains irresponsible and impermissible until relevant scientific, ethical, and societal consensus is achieved.

At the biosafety level, off-target effects represent the most significant practical risk in somatic cell therapy. Although advances in sequencing technology and the development of high-fidelity Cas variants have substantially reduced their frequency, the risk has not been entirely eliminated. In the context of oncology, when editing immune cells, unintended off-target mutations may disrupt key tumor suppressor genes or proto-oncogenes, theoretically posing a potential risk of triggering secondary tumors. Furthermore, even at target sites, CRISPR-mediated double-strand breaks may induce large-scale gene rearrangements or chromosomal abnormalities, leading to genomic instability [78]. Therefore, prior to clinical application, rigorous safety assessments of edited cells must be conducted using sensitive techniques such as whole-genome sequencing to ensure that genotoxic risks are minimized.

In the field of oncology, therapeutic gene editing has also raised a series of unique ethical considerations. First, the high cost may limit access to this cutting-edge therapy to only a select few, thereby exacerbating social inequities in healthcare. Secondly, when editing technology is used to “enhance” immune cell function—such as beyond its natural state—it touches upon the boundary between therapeutic intervention and enhancement. Finally, the informed consent process is particularly critical. It is essential to ensure that patients fully understand this is an emerging therapy whose long-term efficacy and potential risks—such as unknown long-term toxicity—remain incompletely understood. Robust independent ethics committee (IRB) review and a well-developed regulatory framework are the cornerstones for ensuring these therapies advance along an ethical trajectory [79].

CRISPR technology is in constant development. To overcome current technical risks and challenges, future efforts should focus on optimizing delivery mechanisms and reducing off-target effects. Future CRISPR technology will play a greater role in the treatment of GC. It can not only significantly contribute to screening GC genes, aiding in the identification of more key genes, but also provide more treatment methods for GC.

The therapeutic prospects of CRISPR technology in GC organoids offer substantial research potential, enabling GC treatment to be more closely aligned with patient-specific conditions and promoting the advancement of clinical therapies. Gene editing technology holds the promise of curing previously incurable diseases, demonstrating broad application prospects and potential.

CAR-T: chimeric antigen receptor T

CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

CRISPRa: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats activation

CRISPRi: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats interference

crRNA: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats RNA

GC: gastric cancer

HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

m6A: N6-methyladenosine

METTL: methyltransferase-like

PAM: protospacer adjacent motif

PDOs: patient-derived organoids

scFv: single-chain variable fragment

TF: transcription factor

TME: tumor microenvironment

MZ: Writing—original draft. QS: Visualization. QZ: Writing—review & editing. XY: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1476

Download: 24

Times Cited: 0