Affiliation:

1Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Western University, London, Ontario N6A 3K7, Canada

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7953-0337

Affiliation:

2Department of Electrical Electronics Engineering, Kenyatta University, Nairobi 00100, Kenya

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-6352-9926

Affiliation:

2Department of Electrical Electronics Engineering, Kenyatta University, Nairobi 00100, Kenya

Affiliation:

1Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Western University, London, Ontario N6A 3K7, Canada

3Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario N6A 3K7, Canada

Email: joshua.pearce@uwo.ca

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9802-3056

Explor Digit Health Technol. 2026;4:101184 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edht.2026.101184

Received: October 14, 2025 Accepted: December 17, 2025 Published: February 08, 2026

Academic Editor: Khalid Batoo, King Saud University, Saudi Arab

Aim: Neonatal jaundice or neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a common medical condition impacting newborns and pathological jaundice if left untreated, leads to neurological encephalopathy and/or death. The majority of pathological jaundice cases occur in low and middle- income countries (LMIC). Phototherapy has been determined to be the safest and most effective treatment for jaundice. Although inexpensive light-emitting diodes are available on the market, commercial phototherapy devices are expensive (~US$2,000), which creates a barrier to access for these devices in LMIC. Efforts to construct cost-effective phototherapy units have been implemented in the past, but need a method to validate the intensity and wavelength of light received by the infant at a distance away from the source.

Methods: To enable low-cost phototherapy units to be used clinically, this study provides an open-source, low-cost, distributed manufacturing approach to create a light sensor to calibrate phototherapy units. This instrument is a necessary component of any open-source phototherapy treatment used in a clinical setting. This novel instrument was validated by comparing its irradiance and wavelength reading to the commercially calibrated Ocean Insight UV-VIS spectrometer under varying lighting conditions, including that of the existing Datex-Ohmeda Giraffe Spot PT Lite phototherapy equipment accessible through Victoria Children’s Hospital Neonatal Care Ward in London, Ontario, and Kiambu County Hospital in Kenya.

Results: The results of this study have demonstrated that for under US$150, a phototherapy calibration device can be constructed capable of measuring up to 200 uW/cm2/nm with an accuracy of 98.6% and detect the peak wavelength within ±12.5 nm.

Conclusions: It can be concluded that 3D printed open-source irradiance meters are a viable option for calibrating phototherapy units in LMIC to treat hyperbilirubinemia.

Neonatal jaundice or neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is one of the most common medical conditions to affect newborns [1]. Roughly 60% of all newborn infants are diagnosed with jaundice [2, 3]. Most of these cases are of a milder condition—physiological jaundice—and resolve on their own [2, 3]. Pathological jaundice, however, is a far more serious condition, which if left untreated, leads to neurological encephalopathy and/or death [2, 3]. Pathological jaundice accounts for ~25% of diagnoses, which still represents an enormous number of impacted newborns [2, 3]. The majority of cases have been observed to occur in low and middle- income countries (LMIC) [2, 4, 5]. The increased cases of jaundice in LMIC can be attributed to a lack of appropriate medical technology and sustainable processes to treat the condition [5].

The development of neonatal jaundice occurs as a result of the infant’s inability to breakdown and process hemoglobin in the blood [3]. Bilirubin, a compound derived from hemoglobin, can be difficult for an infant to excrete for a variety of reasons including: increased production of bilirubin, deficient conjugation of bilirubin, impaired hepatic uptake, and/or enhanced enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin [3]. Phototherapy, exchange blood transfusions, and intravenous immunoglobulin have been identified as effective treatments for overcoming an infant’s inability to breakdown and process hemoglobin in the blood that causes jaundice [3, 6, 7]. Phototherapy is the most common method to treat hyperbilirubinemia, while exchange transfusion is reserved for the most severe cases [8].

Phototherapy has been determined to be the safest and most effective treatment for jaundice [1, 3, 6, 9–17]. Light of the appropriate wavelength and intensity isomerises bilirubin in the bloodstream into compounds more readily excreted by the body [16–18]. The recommended characteristics of an effective phototherapy device are: peak wavelength between 460–490 nm, irradiance > 30 uW/cm2/nm, and effective treatment area > 2,000 cm2 [9, 14, 19].

The quality of treatment varies with the intensity of light received, and as a case study in Nigerian hospitals presents: the mean irradiance received by the infant was below optimal levels [10]. This is not an isolated event; it is known that the intensity of phototherapy devices decays over time [20]. Simple and affordable methods to maintain the standard of treatment in LMIC are in need [10, 20]. A typical irradiance meter designed to maintain the effectiveness of a phototherapy unit typically costs upwards of $2,000 (Table 1). The high cost creates a barrier to access to these devices in LMIC. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has developed a target product profile which outlines the requirement for a phototherapy unit which is both an effective treatment for jaundice and a cost-effective solution in LMIC [4, 19]. Included in this outline is the requirement that an irradiance meter be made available alongside the unit, such that a clinician can verify the appropriate dosage is administered to the infants.

Market survey of irradiance meters.

Efforts to construct cost-effective phototherapy units have been implemented in the past. A solar-powered phototherapy device [24] used an LDR photo resistor to determine the intensity of light emitted by the source. This method may accurately determine the intensity of light at the source, but cannot provide information about the intensity of light received by the infant at a distance away from the source. Furthermore, this method is unable to verify that the wavelength of the source falls within the recommended range. The open-source irradiance meter described in this paper intends to build upon this work by implementing a separate device to validate the intensity and wavelength at the location of the infant.

One approach to reducing costs for scientific [25–27] and medical equipment [28–30] is the use of open hardware [31]. In the open hardware approach, digital designs of parametric hardware are shared freely on the web, where anyone can download and replicate the device [32]. As the cost of replication is made up of only materials and processing costs, open hardware can generally be manufactured for one-tenth the cost of proprietary hardware [33]. Open-source hardware thus provides the opportunity for access to needed treatments in LMICs and other low-resource settings [34] if an open hardware design is published. In the medical context, open hardware must also be calibrated for clinical acceptance [35]. No such open design or calibration standards have been provided in the literature.

To provide for this need, this paper provides an open-source, distributed manufacturing approach to create a light sensor to calibrate phototherapy units. This instrument is a necessary component of any open-source phototherapy treatment used in a clinical setting. This instrument aims to validate both the wavelength of light produced and the intensity of light received by the patient. It is necessary that this instrument is both low-cost and appropriately calibrated if it is to be used alongside phototherapy devices in LMIC. The instrument was validated by comparing its irradiance and wavelength reading to the commercially calibrated Ocean Insight UV-VIS spectrometer [36] under varying lighting conditions, including that of the existing Datex-Ohmeda Giraffe Spot PT Lite phototherapy equipment [37] accessible through Victoria Children’s Hospital neonatal care ward in London, Ontario, and Kiambu County Hospital in Kenya.

This study details an approach to calibrate an open-source irradiance meter, which in turn can be used to calibrate phototherapy units. The aim is to achieve accurate measurements of the light intensity, ±0.01 uW/cm2 and within a range of 0.01–150 uW/cm2 as described by the UNICEF design catalogue product requirements [21]. Two designs were pursued: (1) using the APDS-9960 sensor [38] built into the Arduino BLE sense [39] shown in Figure 1, and (2) using the AS7265x sensor [40] shown in Figure 2.

Build instructions to create one independently can be found in Supplementary material 1 and 2, respectively. Both devices were exposed to an array of LED’s emitting at a peak wavelength of 455 nm to simulate clinical settings. A calibrated spectrometer was used as the reference to which the irradiance meter was calibrated.

An LED array emitting 455 nm wavelength of light, as verified by a calibrated spectrometer [41], was made to illuminate the uncalibrated irradiance meter, as shown in Figure 3. The spectrometer equipped with a cosine corrector was placed adjacent to the irradiance meter such that they received the same intensity of light. Using the Ocean Insight-OceanView Software Application [42], the absolute irradiance wizard was completed. Scans to average were set to 10, and the boxcar width was set to 10. The irradiance meter was set to output the raw sensor values to the serial line in the Arduino IDE. The pair of instruments was then placed 60 cm from the light source. The peak value measured by the spectrometer, along with the raw data values output by the irradiance meter, were both recorded at that distance for a total of 3 readings. The pair of devices was progressively moved towards the light source while true irradiance and raw output values were recorded. Irradiance vs raw sensor output was plotted, and the linear relationship between the two was determined. The relationship was then implemented into the irradiance meter such that it would calculate the irradiance of the light source using only the sensor value. All the steps were repeated with the irradiance meter equipped with the AS7265x sensor, and the relationship was plotted.

Depending on the sensor used in the build, the resolution of the wavelength reading differs. The built-in APDS-9960 sensor of the Arduino BLE Sense consists of 3 color channels: red—625 nm, blue—465 nm, and green—525 nm. The Sparkfun AS7265x consists of 18 color channel outputs ranging from 410 to 940 nm. First, a calibrated spectrometer was used to confirm the wavelength of the phototherapy light source. Both versions of the 3D printed irradiance meter were then exposed to the same light, and the output was observed.

To create the filter, a tinted sheet of acrylic [43] with dimensions 25 mm × 35 mm × 5 mm was cut. A single layer of clear masking tape [44] was then placed on either side of the sheet. To determine the effect of the filter on the light source, a calibrated spectrometer was used to measure the spectrum of the 455 nm peak lamp source as the reference. The filter was then placed between the lamp source and the spectrometer. The spectrum was measured again and compared to the reference.

To determine accuracy, the light source was fixed at a point while spectral readings were taken at predefined locations of 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, and 60 cm from the source. The irradiance meter was then placed along those same locations, and the values were compared against one another.

Where A is accuracy, Tv is true value, Ov is observed value.

The precision of the device was determined by logging the device readings over a forty-minute period while the light source was held at a constant intensity and distance. The variation in the output was measured to determine the device’s precision.

A variable height test was performed between the open-source light meter and an MTTS light meter [45]. The MTTS light meter has an effective spectral response from 400–520 nm, a measurement range of 0.1–150.0 μW/cm2/nm, and a resolution of 0.1 μW/cm2/nm [45]. The cosine characteristics of the MTTS light meter are ±2% at 30 degrees, ±7% at 60 degrees, and ±25% at 80 degrees with an accuracy or ±3% of reading. Tests were performed with a Photo-Therapy 4000 Jaundice Management machine from Drager [46].

It was found that the APDS-9960 sensor had a linear relationship to the irradiance of the light source. The curve of best fit optimized by least squares regression with an R2 = 0.9947 showed the slope of the relationship as:

where i is irradiance and v is the raw value as shown in Figure 4.

The AS7265x sensor also had a linear relationship to the irradiance of the light source. The curve of best fit optimized by least squares regression with an R2 = 0.9994 showed the slope of the relationship as:

where i is the irradiance and v is the raw value, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 6 plots the spectral output of the phototherapy light to verify that it falls within the 400–500 nm range. Its peak was found to be at 455 nm. Because the APDS-9960 sensor is limited to three color channels at 465, 525, and 625 nm. It can determine that the highest peak is within 465–525 nm, but cannot identify the precise wavelength, nor can it identify a peak with a wavelength below 465 nm with any certainty.

The device using the AS7265x sensor was programmed to indicate that the light source was within range if the largest peak was found in the 435 nm, 460 nm, or 485 nm channel. Figure 7 shows the output of the AS7265x equip device when exposed to the phototherapy source. The AS7265x sensor could verify that the detected wavelength was between 410–485 nm.

The APDS-9960 version did not meet the requirement by the UNICEF Supply Catalogue [21] for detection within 400–500 nm range since wavelengths below 465 are not accurately recorded. The AS7265x meets the requirement by the UNICEF Supply Catalogue [21] for detection within 400–500 nm range.

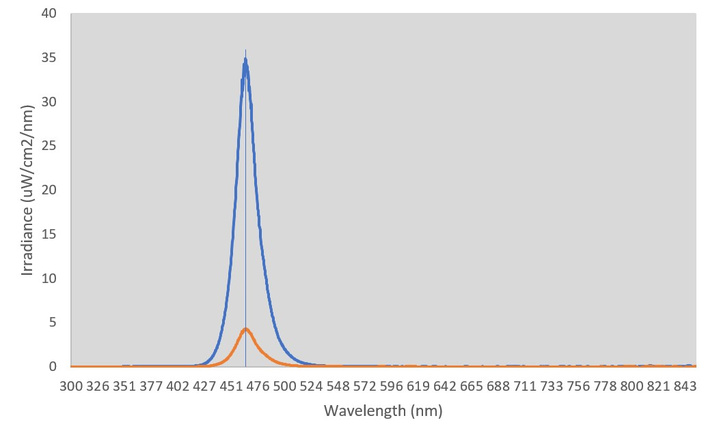

The results of the filter test are shown in Figure 8. As can be seen, the peak of both the source and the filtered light occurs at 455 nm; therefore, the filter does not cause any spectral shift in the 455 nm range. Secondly, the peak irradiance of the spectrum with the filter is significantly lower. Thus, the intended effect of the filter has been achieved. The maximum exposure of the sensor has been lowered such that it will operate within the desired range, and the wavelength of light was verified not to shift as a consequence of passing through said filter.

Effect of filter on phototherapy light (yellow with filter and blue without filter).

The true value compared with that of the AS7265x sensor can be observed in Table 2. The final accuracy is 98.64% using Equation 1.

Comparison of true value vs AS7265x irradiance reading.

| Distance (cm) | True value (uW/cm2/nm) | Irradiance meter reading (uW/cm2/nm) | Delta | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 22.5 | 22.37 | 0.13 | 0.9942 |

| 50 | 32.17 | 32.42 | 0.25 | 0.9922 |

| 40 | 48.32 | 49.73 | 1.41 | 0.9708 |

| 30 | 79.88 | 80.15 | 0.27 | 0.9966 |

| 25 | 104.36 | 104.43 | 0.07 | 0.9993 |

| 20 | 145.33 | 143.12 | 2.21 | 0.9848 |

| 15 | 208.32 | 201.35 | 6.97 | 0.9665 |

Figure 9 plots the irradiance meter readings over 40 minutes while exposed to a fixed light source. The AS7265x irradiance meter outputs an average value of 21.74 ± 0.04 uW/cm2/nm.

The true value compared with that of the APDS-9960 sensor can be observed in Table 3. The final accuracy is 90.40% using Equation 1.

Comparison of true value vs APDS-9960 irradiance reading.

| Distance (cm) | True value (uW/cm2/nm) | Irradiance meter reading (uW/cm2/nm) | Delta | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 17.21 | 19.45 | 2.24 | 0.8698 |

| 50 | 23.84 | 27.18 | 3.34 | 0.8599 |

| 40 | 36.78 | 39.99 | 3.21 | 0.9127 |

| 30 | 58.2 | 63.95 | 5.75 | 0.9012 |

| 25 | 78.55 | 84.17 | 5.62 | 0.9285 |

| 20 | 109 | 117.59 | 8.59 | 0.9212 |

| 15 | 154.68 | 164.8 | 10.12 | 0.9346 |

| 10 | 242.78 | 243.17 | 0.39 | 0.9984 |

Figure 10 plots the irradiance meter readings over 40 minutes while exposed to a fixed light source. The AS7265x irradiance meter outputs an average value of 32.92 ± 0.71 uW/cm2/nm.

The validation results on the Photo-Therapy 4000 Jaundice Management machine from Drager in an LMIC are shown in Table 4.

Light meter responses as a function of distance from a Photo-Therapy 4000 Jaundice Management machine.

| Distance from light(cm) | OS light meter(uW/cm2/nm) | MTTS(uW/cm2/nm) | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 18.4 | 21 | 0.124 |

| 25 | 36.6 | 36 | 0.017 |

| 30 | 45.05 | 42 | 0.073 |

| 40 | 50.05 | 51 | 0.019 |

| 50 | 68.18 | 69 | 0.012 |

| 60 | 79.3 | 79 | 0.004 |

As can be seen by the results in Table 4, the results of the open-source light meter are in good agreement with the commercial MTTS system at larger distances that would be clinically relevant. The greater errors observed at small distances are due to cosine errors and expected.

This paper has demonstrated that a 3D printed irradiance meter using the AS7265x sensor is an effective device to calibrate phototherapy light sources. Irradiance can be measured up to 200 uW/cm2/nm, surpassing the UNICEF requirements [21], with an accuracy of 98.6%, and will determine the wavelength of peak spectrum with an accuracy of ±12.5 nm. Over a forty-minute period the device is stable within ±0.04 uw/cm2/nm. The additional cost of the AS7265x sensor, however, may be a consideration for use cases in LMIC.

The APDS-9960 sensor meets the spectral irradiance range requirements of 150 uW/cm2/nm. Compared to the AS7265x sensor, the APDS-9960 is limited in its ability to verify wavelength and provides less accurate readings of irradiance intensity. The APDS-9960 only validates wavelengths between 465–525 nm so does not meet the wavelength requirements set out by the UNICEF supply datasheet [21]. Given the lower accuracy, lower precision, and limited wavelength reading, the APDS-9960 version is not generally recommended [14]. In highly resource constrained settings the APDS-9960 version may be considered with the understanding that the device is rated only for LED sources with a peak above 465 nm.

As previous work has shown, effective treatment of hyperbilirubinemia is commonly administered through light therapy of 400–500 nm with an intensity greater than 30 uW/cm2/nm. The light source was verified by a calibrated spectrometer (Figure 6), providing consistency between previously published work and the work shown here.

It has been demonstrated that for under $200 CAD, one can construct a phototherapy calibration device capable of measuring up to 200 uW/cm2/nm with an accuracy of 98.6% and detect the peak wavelength within ±12.5 nm. 3D printed open-source irradiance meters are a viable option for calibrating phototherapy units in LMIC to treat hyperbilirubinemia.

Consideration should be made for the long-term performance of the device. The PLA housing of the device is not expected to degrade as long as the device is protected from outside elements [47]. Voltage regulation is managed on board the Arduino nano, while additional regulation is provided in the battery bank of models using a portable battery (Supplementary material 3). Future work may focus on the long-term stability of the device, and on the period recalibration of the unit is required.

LMIC: low and middle- income countries

UNICEF: United Nations Children’s Fund

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/101184_sup_1.pdf.

The authors would like to thank C. Brooks and G. Antonini for helpful discussions.

JTMG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JMP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Files, code, and data can be found at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/7dqp6/, DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/7DQP6.

This work was supported by the Thompson Endowment and Frugal Biomed Catalyst Grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 280

Download: 12

Times Cited: 0