Affiliation:

1Department of Internal Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—Northwest Regional Campus, Fayetteville, AR 72703, United States of America

Email: sahilsabh12@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4660-2169

Affiliation:

2College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—Northwest Regional Campus, Fayetteville, AR 72703, United States of America

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-3019-5376

Affiliation:

3Health Orlando Incorporated, Orlando, FL 32744, United States of America

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5925-3682

Affiliation:

3Health Orlando Incorporated, Orlando, FL 32744, United States of America

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2869-715X

Affiliation:

4Department of Gastroenterology, Mercy Hospital Northwest Arkansas, Rogers, AR 72758, United States of America

Explor Dig Dis. 2026;5:1005111 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2026.1005111

Received: November 21, 2025 Accepted: February 01, 2026 Published: February 13, 2026

Academic Editor: Jose C. Fernandez-Checa, Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona (IIBB-CSIC), Spain

Herpes simplex esophagitis (HSE) is a viral infection of the esophagus caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), most commonly HSV-1. It predominantly presents among immunosuppressed individuals. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease characterized by significant eosinophilic infiltration in the esophageal mucosa. It is often associated with atopic diseases, including asthma, food allergies, and eczema. Coexistence of HSE and EoE is rare and may be underdiagnosed due to challenges in diagnosing both conditions simultaneously. A major diagnostic dilemma can be traced to their histopathological similarities and differences. HSE is typically characterized by multinuclear giant cells containing intranuclear inclusions, while EoE involves eosinophilic infiltration in the esophageal epithelium. This report highlights the rare but remarkable coexistence between HSE and EoE secondary to a unique patient case. Although each condition may cause esophagitis individually, together—particularly in immunocompetent individuals—they do present a different diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Herpes simplex esophagitis (HSE) is a viral infection of the esophagus caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), most commonly HSV-1. It predominantly presents among immunosuppressed individuals, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer, or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. The clinical manifestations accompanying HSE include odynophagia, dysphagia, and chest pain. In more severe cases, endoscopic evaluation may reveal esophageal ulceration. The diagnosis is often confirmed by histopathological analysis showing multinucleated giant cells with intranuclear inclusions. Although HSE is uncommon in individuals with a healthy immune system, rare cases have been reported, which are usually associated with transient immunodeficiency or other predisposing factors [1, 2].

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease of the esophagus, characterized by significant eosinophilic infiltration in the mucosa. It is often associated with atopic diseases, asthma, food allergies, and eczema. T helper 2 (Th2)-type immune response, triggered by food antigens or airway allergens, is considered to be the primary mechanism of inflammation and esophageal dysfunction in EoE. Clinically, EoE presents similarly to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), such as dysphagia, food impaction, and chest discomfort. Diagnosis is supported by endoscopic biopsies revealing eosinophil counts greater than 15 eosinophils per high-power field in the esophageal epithelium, after ruling out other causes for esophageal eosinophilia [3, 4].

Recent studies suggest an association between HSE and EoE. While both conditions are independently recognized as causes of esophagitis, their co-occurrence in an immunocompetent patient prompts intriguing questions regarding possible shared pathogenic mechanisms. It is hypothesized that mucosal erosion caused by EoE creates an environment predisposing the esophagus to secondary infection with HSE. Conversely, HSE infection might induce eosinophilic infiltration in the esophagus, thereby contributing to the development of EoE. As the relationship between HSE and EoE remains unclear, further research is necessary to explore whether a bidirectional association exists between these two conditions [5–7].

This case report and review compile the existing evidence on the potential association between HSE and EoE. It examines case reports, clinical investigations, and theoretical models to explore possible mechanisms explaining their simultaneous occurrence, while also addressing the clinical implications for both diagnosis and therapeutic strategies. Importantly, this relationship can enhance further patient care, especially for those with esophageal symptoms that might be related to either or both conditions.

The timeline of the patient’s clinical course is summarized in Table 1.

Timeline of clinical course, diagnostic evaluation, and management in an 18-year-old immunocompetent patient with concurrent herpes simplex esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

| Visit type | Visit/setting | Symptoms/concerns | Assessment/workup | Management/outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial visit | Outpatient visit/primary care | Odynophagia, solid-food dysphagia (worse with meat), heartburn, epigastric pain, occasional globus sensation | Clinical evaluation | Began proton pump inhibitor once daily (planned 8 weeks) and systemic corticosteroids daily for 5 days; symptoms improved. Referred to GI. Medication details: omeprazole 20 mg daily for eight weeks and a five-day course of prednisolone 15 mg/mL daily. |

| GI evaluation | GI clinic | Persistent or recurrent dysphagia/odynophagia prompting evaluation | Planned EGD | Proceeded to EGD with biopsies. |

| EGD | Endoscopy suite | Dysphagia/odynophagia with reflux symptoms | EGD: Los Angeles Grade B reflux esophagitis, no bleeding; biopsies obtained | Pathology later showed findings consistent with HSE and EoE. |

| Pathology result review | Follow-up/results | Review of dual diagnosis | Histopathology consistent with HSV cytopathic effect and esophageal eosinophilia | Antiviral therapy initiated for HSE; plan to address EoE after viral management.Medication details: acyclovir 400 mg five times daily for ten days, followed by omeprazole 20 mg daily. |

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EoE: eosinophilic esophagitis; GI: gastroenterology; HSE: herpes simplex esophagitis; HSV: herpes simplex virus.

An 18-year-old man with a history of asthma presented with odynophagia and solid-food dysphagia, particularly with meat, accompanied by heartburn, epigastric pain, and occasional globus sensation (Table 1). His mother reported an episode of esophagitis at age three that improved with avoidance of specific foods (including dairy, codfish, oranges, and peanuts). The patient reported that he had outgrown most childhood food allergies, with milk as his only persistent allergy. He had not previously undergone esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and denied any first-degree family history of esophageal, gastric, or colon cancer.

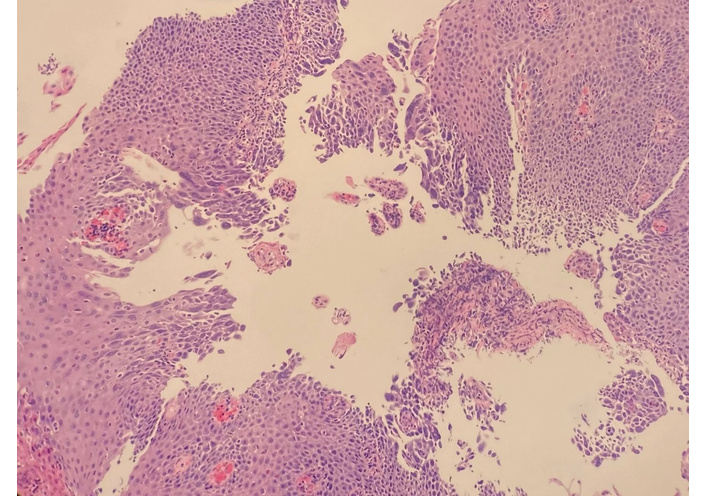

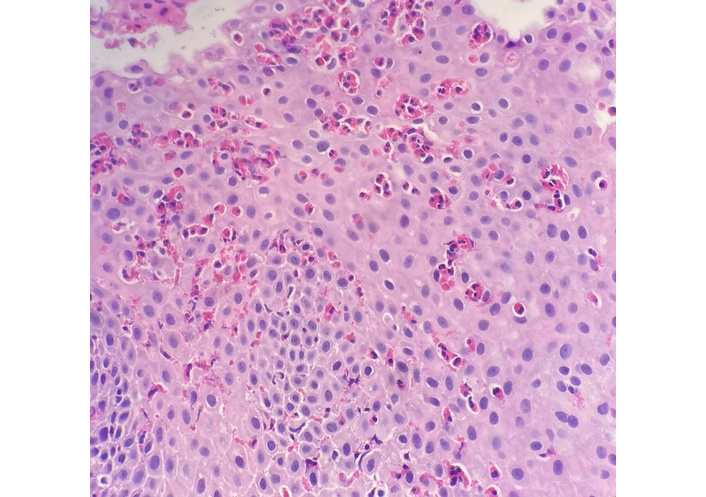

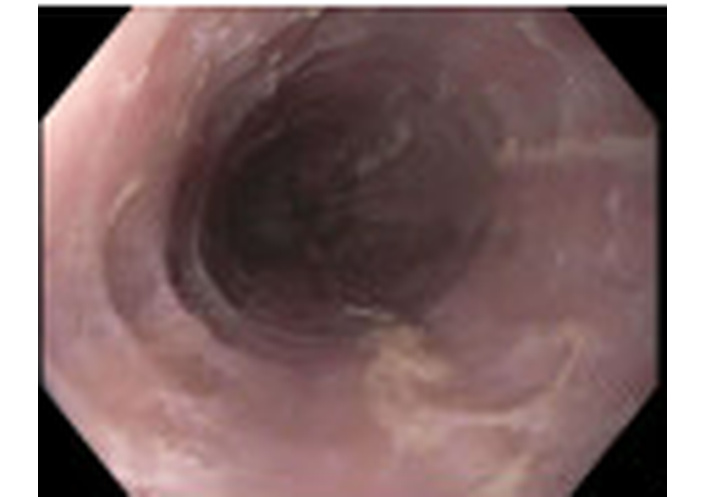

He was empirically treated with omeprazole 20 mg daily for eight weeks and a five-day course of prednisolone 15 mg/mL daily, which resulted in improvement of symptoms. Due to the clinical presentation and history suggestive of esophageal inflammation, he was referred to gastroenterology and underwent EGD. Endoscopy demonstrated Los Angeles Grade B reflux esophagitis without bleeding. Multiple biopsies were obtained. Histopathology demonstrated viral cytopathic changes consistent with HSE (Figure 1) and eosinophil-predominant inflammation consistent with EoE (Figure 2). EGD also demonstrated Los Angeles Grade B reflux esophagitis without bleeding (Figure 3 and Table 2). Diagnosis of HSE was made morphologically based on characteristic herpesvirus cytopathic effect on hematoxylin and eosin staining; HSV immunohistochemistry (IHC) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were not performed. Acyclovir 400 mg five times daily for ten days was initiated for antiviral therapy for HSE with a plan for subsequent management of EoE with omeprazole 20 mg daily following control of the viral process. Unfortunately, after initiation of EoE treatment, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Pathologic specimen from the esophagus demonstrating cytologic features consistent with herpes simplex virus. The arrow indicates squamous cells with intranuclear inclusions and multinucleation. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification: 10×.

Pathologic specimen exhibiting benign squamous mucosa with a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate, consistent with eosinophilic esophagitis. The arrows indicate intraepithelial eosinophils. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification: 20×.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy demonstrated Los Angeles Grade B reflux esophagitis without bleeding.

Summary of diagnostic evaluations, results, and interpretations.

| Test | Result | Normal/reference | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGD | LA Grade B reflux esophagitis; no bleeding. | N/A | Endoscopic evidence of esophagitis |

| Esophageal biopsy (HSV features) | Morphologic features of herpesvirus infection on hematoxylin and eosin staining (multinucleation, nuclear molding, and intranuclear inclusions); HSV immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction were not performed. | No viral cytopathic changes | Consistent with herpes simplex esophagitis |

| Esophageal biopsy (eosinophilia) | Prominent eosinophilic infiltrate, peak 135 eos/hpf. | Typically < 15 eos/hpf | Consistent with eosinophilic esophagitis |

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy; HSV: herpes simplex virus.

The diagnostic evaluation included endoscopy with tissue sampling. EGD revealed Los Angeles Grade B reflux esophagitis without bleeding. Esophageal biopsies demonstrated (1) viral cytopathic changes consistent with HSV infection and (2) eosinophil-predominant inflammation consistent with EoE.

The patient described symptoms of heartburn and epigastric pain along with difficulty swallowing solid foods, particularly meat, and noted occasional globus sensation. He reported relief of symptoms after starting once-daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for 8 weeks and daily steroid therapy for 5 days. There were little to no financial, cultural, or access to testing diagnostic challenges disclosed by the patient.

HSE and EoE are distinct causes of esophagitis but can co-exist, creating diagnostic and therapeutic challenges even in immunocompetent patients.

Marella et al. [4] (2021) described a case in which a known case of HIV infection was diagnosed with concomitant HSE and EoE. Similar cases suggest the possibility that these conditions might have a propensity to co-exist, particularly in patients with some level of underlying immune dysfunction.

Another significant case was presented by Quera et al. [5] (2021), involving a 26-year-old immunocompetent patient with HSE. The patient presented with chest and retrosternal pain and was initially diagnosed with HSE endoscopically, but later, histological findings revealed EoE.

In the case presented by Patel et al. [8] (2022), a young adult presented with odynophagia and dysphagia. Endoscopic biopsy revealed typical viral inclusions, confirming the initial diagnosis of HSE. Later, the patient developed persistent dysphagia and food impaction, characteristic of EoE, leading to the subsequent diagnosis of EoE. This case illustrates that HSE can occur either preceding or following the development of EoE, suggesting that the inflammatory background set up by HSE might have unmasked or precipitated the evolution of EoE [8, 9].

Iriarte Rodríguez et al. [10] (2018) reported esophageal eosinophilia identified after treatment for HSE, raising the possibility that post-infectious inflammation may reveal underlying EoE.

Prior reports include both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients across pediatric and adult age groups, but the literature remains limited to case reports and small series.

The demographic ranges from pediatric and adult populations, with differing immune statuses. While many case reports were from young adults, particularly young adult males, this is likely attributable to the limited sample size. Larger epidemiologic studies are needed to confirm these trends.

Co-existence of HSE and EoE is uncommon and may be underrecognized because symptoms overlap, and both diagnoses require targeted biopsies. Both conditions can present with dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort.

The overlapping clinical features of HSE and EoE highlight the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup, not only in patients with active esophageal symptoms but also for those whose initial treatments are ineffective. Clinicians should consider the possibility of dual pathology in patients who continue to experience symptoms despite antiviral therapy for HSE and a history of atopic conditions.

Complexity emerges not only due to overlapping symptoms but also due to additional unique co-existing conditions. Bustamante Robles et al. [6] (2017) highlight that the association remains controversial and reported immunocompetent cases with both conditions. This suggests the co-existence of such esophageal conditions complicates the diagnostic process since health professionals may prioritize more severe or prominent symptoms, potentially overlooking other conditions.

A major diagnostic dilemma for both HSE and EoE can be traced to their histopathological similarities and differences. HSE is typically characterized by multinucleated giant cells containing intranuclear inclusions, while EoE involves eosinophilic infiltration in the esophageal epithelium. Although IHC or PCR can be used in challenging cases, the diagnosis in this case was based on classic morphologic findings without ancillary testing. Determining which condition is the primary cause of symptoms becomes difficult when both coexist, particularly in cases of limited biopsy material or when esophageal lesions are not evident enough to suggest the dual pathology. Moreover, the viral inclusions in HSE may obscure the more subtle histologic features of EoE, particularly when the biopsy is suboptimal or the sampled area is more heavily affected by the virus.

Other challenges may include one condition masking the other during initial screenings. For instance, inflammation secondary to HSE can suppress eosinophilic activity, leading to false-negative diagnoses for EoE in early biopsy samples. Conversely, chronic inflammation from EoE may obscure the acute changes of HSE, especially if antiviral therapy is initiated before a definite diagnosis of HSE is made.

Accurate diagnosis is closely tied to recognizing esophageal symptoms. Bustamante Robles et al. [6] (2017) emphasized that neglecting the diagnosis of one of these conditions would result in partial treatment and persistence of the symptoms. Endoscopy with biopsies from multiple esophageal levels and careful attention to atopic history improves the detection of dual pathology.

The simultaneous development of HSE and EoE presents with unique diagnostic challenges. Its low incidence, subtle symptoms, and intricate histopathological features highlight the importance of heightened clinical suspicion and a multidisciplinary approach. Recognizing that these conditions frequently co-exist allows for more targeted diagnostic testing and leads to more effective therapeutic interventions.

The mucosal barrier disruption hypothesis is one of the simplest hypotheses regarding the co-occurrence of HSE and EoE. Chronic eosinophil-predominant inflammation in EoE can compromise epithelial integrity through changes such as basal cell hyperplasia, dilated intercellular spaces, and remodeling, which may allow HSV to penetrate inflamed mucosa more readily. Zimmermann et al. [1] (2016) reported HSE in patients with active EoE, supporting the concept that local barrier dysfunction in EoE may predispose to HSV infection even in otherwise immunocompetent individuals. In their series, they described five cases of severe HSE in patients with active EoE, four of whom had not previously been treated for EoE.

It remains unclear whether chronic immune cell recruitment in EoE promotes HSV persistence; however, eosinophils and other recruited cells can secrete cytokines and chemokines that may alter the local immune environment and contribute to ongoing mucosal injury, potentially increasing susceptibility to opportunistic infection.

Alterations in the immune response may also contribute. HSV infection triggers a robust inflammatory response and may amplify local cytokine signaling; in predisposed patients, this inflammatory milieu could unmask or worsen Th2-skewed pathways associated with EoE, including eosinophil recruitment and persistence [5, 6].

HSV-driven inflammation may also promote immune cross-reactivity, in which antiviral responses contribute to heightened reactivity to other antigens (for example, food or environmental allergens), sustaining eosinophilic inflammation. Ongoing EoE-associated immune dysregulation may then make HSV harder to eradicate, creating a potential vicious cycle of inflammation and mucosal damage that can worsen both conditions. This framework supports considering dual pathology when symptoms overlap or when the clinical course does not fit a single diagnosis.

Transient immunosuppression is another plausible contributor. Corticosteroid exposure can suppress antiviral immune responses and may increase the risk of HSV progression or delay clearance, which is clinically relevant when infectious esophagitis has not yet been excluded [11].

This is clinically important because EoE therapy often includes corticosteroids; if steroids are started before HSV is recognized, timing and escalation of immunosuppression could theoretically exacerbate active infection, while prioritizing antiviral therapy first may mitigate this risk.

The co-existence of HSE and EoE can be attributed to a few plausible pathophysiological hypotheses, including disruption of the mucosal barrier, modification of the immune response, and consequences of temporary immunosuppression. These mechanisms do not function in isolation but instead function in a complex manner. Complete elucidation of such interactions will be relevant to the structuring of appropriate treatment strategies and successful outcomes in patients with both conditions.

In our case, the patient received a 5-day course of systemic corticosteroids before endoscopy and before HSE was recognized. Systemic corticosteroids can theoretically worsen active HSV infection or delay viral clearance by reducing cell-mediated immune responses, and therefore may increase risk when infectious esophagitis remains in the differential diagnosis of odynophagia or dysphagia. In retrospect, the short duration of exposure, the patient’s immunocompetent status, and concurrent acid suppression may have limited harm in this instance, but this approach is not ideal. When infectious esophagitis is a reasonable possibility, early endoscopy with biopsy before starting systemic corticosteroids is preferred; if steroids are used empirically, they should be limited to the lowest effective dose, and reassessment should occur promptly, with antiviral therapy prioritized if HSV is identified.

Treatment of HSE is imperative since antiviral drugs, particularly acyclovir, could lead to a cure and removal of the HSV from esophageal tissue. If treatment of HSE is delayed, continued viral replication may cause further esophageal injury and make EoE more difficult to treat.

HSE antiviral treatment can be initiated based on a combined diagnosis of HSE and EoE. In doing so, it is important to note that symptom resolution is not always completely related to the virus. Follow-up endoscopy showing that HSE has resolved may be wise prior to commencing with EoE management. This approach will help guard against potential drug interactions between treatments of the viral infection and EoE.

Treatment of EoE typically involves PPIs and topical corticosteroids, which can inadvertently delay the healing of esophageal tissue in situations where HSE is active. Viral-directed therapy provides a more accurate assessment of the severity of EoE, prevents accidental worsening of HSE with more treatment, and focuses on eliminating the underlying cause. The stepwise management approach minimizes the risk of an adverse outcome, which is essential when managing both conditions simultaneously.

Given the chronic nature of EoE, long-term management and monitoring are important. HSV esophagitis in immunocompetent children may be associated with underlying or subsequently recognized EoE. It is reported that EoE was a comorbidity in nearly half of immunocompetent children with HSV esophagitis. Fritz et al. [12] (2018) highlight the necessity of clinical follow-up in patients, particularly in those with atopic conditions.

As EoE is a chronic illness, ongoing care is also necessary to avoid complications such as esophageal fibrosis and stricture. Follow-up endoscopies may be needed, with therapeutic plans modified according to findings. This is especially important in patients with HSE, as it is crucial to know whether the virus has reactivated or the patient has developed new lesions. Immune dysregulation in EoE may worsen, thus increasing vulnerability to future recurrences of HSE. Clinicians should have a high level of suspicion for HSE in patients with EoE presenting with either new-onset or worsening symptoms despite ongoing maintenance therapy for EoE.

In addition to regular endoscopic surveillance, other long-term management suggestions include raising patient awareness of HSE and EoE symptoms. Patients and their caregivers need to be aware of the recurrence risk of each disease and, should symptoms reappear, understand the importance of early action. Early detection can prevent the worsening of the EoE or further injury to the esophagus.

Frequent follow-up visits allow for adjustment of corticosteroid doses or transitioning to alternate therapies, with the intent to manage EoE against the risk of viral reactivation.

With a holistic view taken by the multidisciplinary care team, long-term management of HSE and EoE can be effective. Implementing these strategies will improve the overall prognosis of patients affected by this pair of complex conditions.

This case report highlights the rare but remarkable co-existence between HSE and EoE. Although each condition may cause esophagitis individually, together, particularly in immunocompetent individuals, they do present a different diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. A review of case reports and studies reveals that although the interaction may be rare, it can be clinically significant.

One of the main conclusions from the literature is that EoE can offer a pathway to susceptibility to HSE through mechanisms such as disruption of the mucosal barrier. Chronic inflammation and morphologic changes of the esophageal mucosa in EoE can also be a predisposing factor for the penetration of HSV into the tissue [1]. This immune response against HSE, in conjunction with eosinophil-sensitive esophagitis, could be worsened with respect to the bidirectional relationship between the two conditions [5, 10].

After an extensive literature review regarding the treatment of patients showing symptoms that could be related to both HSE and EoE, the clinical guidelines can be summarized as follows:

HSE treatment precedence: Prioritizing the potential exacerbation of HSE that might result from the highly immunosuppressive therapies used with the goal of overcoming EoE [13].

Full diagnostic work-up: Patients with esophageal symptoms should undergo a comprehensive investigation using endoscopy. Biopsies from various sites throughout the esophagus should be obtained. This will increase the yield of a correct diagnosis of accompanying HSE and EoE if it happens to co-exist, thus allowing relevant diagnosis and management of the disease process accordingly [6].

Patient education and monitoring: Emphasize follow-up care, including periodic endoscopic monitoring [12].

Consider alternate treatment modalities for EoE: Treatment of EoE with a concomitant response to eosinophilic inflammation has included dietary or biological approaches [8].

Despite the understanding gained from the available literature, there are myriad deficiencies that further studies must focus on:

Larger epidemiological studies: Much of the current information concerning the coincidence of HSE and EoE has been provided in case reports and small series. Larger epidemiological studies are needed to establish a deeper understanding of this relationship, particularly with various demographic groups relating to prevalence and risk factors in developing both conditions.

Mechanistic studies on immune interactions: The interaction between HSE and EoE is not yet fully understood. Focused research on the immune interactions occurring between HSV and eosinophilic inflammation in EoE may uncover valuable insights into how the diseases influence each other for further treatments.

Longitudinal treatment outcomes: Extended studies are required to evaluate the outcomes related to different therapeutic strategies, including, but not restricted to, timing and choice of therapy in subjects with HSE and EoE. These studies may refine the guidelines further and, more importantly, improve the long-term prognosis for these patients.

Investigation of new therapeutic modalities: Given the complex management strategies for HSE and EoE, new therapeutic modalities need to be investigated that could treat both conditions without exacerbating either. Research will also be required in order to test whether biologics or other targeted therapies aimed at suppressing the immune response result in a loss of effective viral control.

Further study will enable clinicians to continue refining approaches to the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of these complex esophageal disorders.

This case presentation shows strong clinicopathologic correlation for the coexistence of HSE and EoE, supported by endoscopic findings with biopsies, an extremely high peak eosinophil count of 135 per high-powered field, and supporting histopathologic images, in addition to an organized timeline approach and an analysis of existing literature in the context of likely mechanistic hypotheses. The limitations of this study include single-case analysis, lack of follow-up HSV IHC or PCR analysis other than conventional hematoxylin-eosin staining, and loss to follow-up to determine long-term outcomes in this patient post-EoE treatment. Causality or inferential associations for either condition in relation to EoE or HSE, respectively, have not been established, suggesting that large-scale studies in these two conditions are indicated.

Empiric systemic corticosteroids may provide symptom relief but can carry theoretical risk in undiagnosed infectious esophagitis; when HSV is suspected or confirmed, antiviral therapy should be initiated before EoE-directed corticosteroid therapy.

With the incidence of EoE steadily increasing, clinicians should consider dual etiologies such as HSE and EoE when evaluating esophagitis, even in immunocompetent patients. Additional studies are needed to clarify directionality, mechanisms, and optimal sequencing of therapy when both entities are present. With increased research and awareness, alleviation of suffering, improvement of outcomes, reduction of complications, and optimum treatment of patients suffering from these complex disorders will follow.

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy

EoE: eosinophilic esophagitis

IHC: immunohistochemistry

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

HSE: herpes simplex esophagitis

HSV: herpes simplex virus

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

PPI: proton pump inhibitor

Th2: T helper 2

The abstract was originally presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Conference 2025 in Phoenix, Arizona https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2025/10002/s4309_intersecting_pathologies__herpes_simplex.4308.aspx. The abstract, on conference acceptance, was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. However, the abstract has since been modified to fit the requirements of this journal. The publication of this manuscript and the data involved in other journals is not affected by the conference organizers.

SS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. BY: Writing—original draft. DS: Writing—review & editing. SCS: Writing—review & editing. TO: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

There is a familial relation between the authors Sahil Sabharwal, Deepak Sabharwal, and Sarat C. Sabharwal. The authors declare that this relationship did not influence the work, and there are no conflicts of interest. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

This case report was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences was not required for the publication of a single de-identified case report in accordance with institutional policy.

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from the relevant participant, including consent for publication of any accompanying images.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 347

Download: 14

Times Cited: 0