Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

2China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation, Beijing 100728, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3423-4089

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

Affiliation:

1SINOPEC Nanjing Research Institute of Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210048, Jiangsu, China

2China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation, Beijing 100728, China

3College of Material Science and Engineering, Donghua University, Shanghai 201620, China

Email: ytduan211@outlook.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8235-0623

Explor BioMat-X. 2026;3:101358 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2026.101358

Received: November 22, 2025 Accepted: January 28, 2026 Published: February 06, 2026

Academic Editor: Rashid K. Abu Al-Rub, Khalifa University, UAE

Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) is widely used as a key material in biomedical implants such as artificial joints due to its exceptional wear resistance, high impact strength, and good biocompatibility. However, its inherent bio-inertness, hydrophobicity, risk of osteolysis induced by wear debris, and insufficient mechanical and processing properties severely limit its long-term clinical performance. This review systematically summarizes recent advances in the functional enhancement of UHMWPE via hybrid strategies, including surface modifications (e.g., coatings, chemical grafting, laser processing, plasma treatment) and bulk blending modifications (involving both organic and inorganic composites). These approaches have been shown to significantly improve wear resistance, bioactivity, hydrophilicity, and mechanical properties, while effectively suppressing oxidative degradation and inflammatory responses. The current challenges in modification technologies, such as balancing multiple properties, ensuring long-term biosafety, and achieving clinical translation, are also discussed. Finally, future directions toward multifunctional integration, intelligent responsiveness, and personalized customization of implants are outlined, providing critical insights for the development of next-generation high-performance and long-lasting biomedical materials.

Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), defined by a molecular weight (MW) typically exceeding 1.5 × 106 g·mol–1, derives its distinctive portfolio of properties from the extreme length and linear architecture of its polymer chains [1–5]. These molecular characteristics are directly responsible for its outstanding wear resistance, which is approximately four times superior to that of stainless steel in sliding contact and three to five times greater than that of conventional polyethylene [6]. The material also exhibits an exceptional combination of high strength and toughness, with reported impact strengths often surpassing 100 kJ·m–2, complemented by excellent fatigue endurance [7–9]. From a biological standpoint, UHMWPE demonstrates high biocompatibility, showing no significant cytotoxicity and a minimal propensity to provoke adverse immune reactions in vivo [10–12]. Further enhancing its suitability for demanding applications are its low coefficient of friction (generally in the range of 0.05–0.10), which confers self-lubricating behavior, high chemical stability against a wide spectrum of acids, alkalis, and organic solvents, and remarkable retention of mechanical properties even at cryogenic temperatures as low as –269°C [13–15].

Owing to this unique portfolio of properties, UHMWPE has been widely adopted across a range of demanding fields. In the biomedical sector, it is a material of choice for critical implant components such as acetabular liners in hip and knee replacements and suture cables for bone fixation, contributing significantly to the long-term performance and reliability of prosthetic devices [16–21]. In mechanical engineering, UHMWPE is employed in wear-resistant parts, including guide rails, gears, and bearings, where it helps minimize equipment wear and energy consumption [22–25]. The material also plays a vital role in national defense and security, where UHMWPE fibers are incorporated into body armor and composite armor systems, offering lightweight yet high-strength ballistic protection [26, 27]. Applications in transportation include ship fenders and rail guides, leveraging its high impact and abrasion resistance to improve durability and service life [6, 15]. The textile industry utilizes UHMWPE to manufacture high-performance fibers for specialized protective clothing and aerospace components. Moreover, UHMWPE has become a key material in lithium-ion battery separators [28], benefiting from its high mechanical strength, chemical inertness, capacity to form highly porous structures conducive to lithium-ion transport, and inherent thermal shutdown functionality—collectively enhancing battery safety and operational stability [29–33]. Thus, through these diverse applications, UHMWPE provides critical material solutions that underpin performance advances in multiple high-technology domains.

The commercial production of UHMWPE primarily relies on a low-pressure slurry polymerization process [34–36]. The core technology involves the use of a highly efficient Ziegler-Natta catalyst system, typically composed of a titanium-based compound (e.g., titanium tetrachloride) and an alkylaluminum cocatalyst (e.g., triethylaluminum) [37–39]. Under mild conditions, typically at temperatures of 50–80°C and pressures below 10 bar, ethylene monomers undergo coordination polymerization in an inert diluent (e.g., hexane) [40–43]. The active centers of the catalyst precisely control the insertion mode of the monomers, resulting in a polymer with extremely high linearity and MW. Critical control over the MW and its distribution of the final product is achieved by meticulously optimizing the structure of the catalyst support (e.g., magnesium chloride), the use of electron donor modifiers, and polymerization parameters, such as the partial pressure of hydrogen, which acts as a chain transfer agent to regulate MW [26, 44–47]. Upon completion of the polymerization, the resulting slurry undergoes post-treatment processes, including deashing, washing, and drying, to remove catalyst residues, yielding a final white powder resin [48]. Furthermore, the development of single-site catalysts, such as metallocene systems, offers new possibilities for the tailored synthesis of UHMWPE with narrower MW distributions and specific chain structures. Nevertheless, the Ziegler-Natta method remains the dominant industrial technology due to its maturity and cost-effectiveness [49].

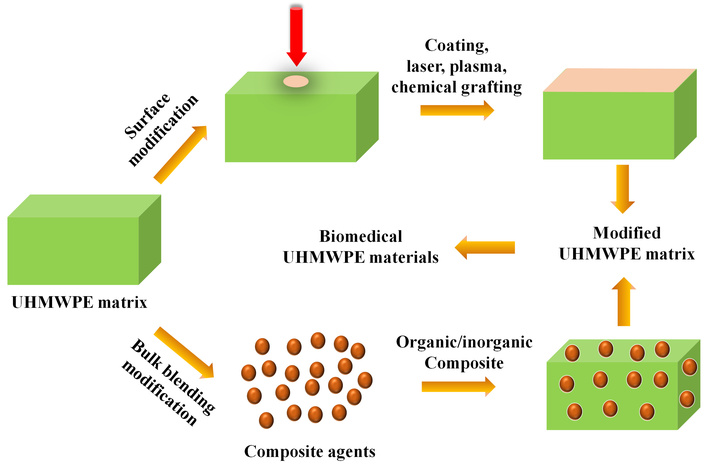

Notably, UHMWPE is a critical material for biomedical implants, particularly in joint replacements, due to its excellent wear resistance, high impact strength, and good biocompatibility. However, its inherent bio-inertness, hydrophobicity, tendency to generate wear debris that can lead to osteolysis, insufficient mechanical properties such as low surface hardness and heat distortion temperature, and processing challenges collectively limit its long-term clinical performance. These limitations underscore the urgent need for material modification to develop next-generation, long-lasting implants [50–54]. Addressing these through material modifications is essential to extend implant longevity, enhance biocompatibility, and introduce vital functionalities, all of which are crucial for reducing revision surgeries and improving patient outcomes [55–58]. Modification strategies are primarily divided into surface and bulk techniques [59–62] (Figure 1). Key surface approaches include the application of wear-resistant coatings [e.g., diamond-like carbon (DLC)], chemical grafting of bioactive molecules to direct cellular responses, and laser or plasma treatments to engineer surface topography and chemistry [63–69]. For bulk enhancement, strategies involve blending with polymers like high-density polyethylene (HDPE) to improve processability, or forming inorganic composites with reinforcements such as graphene oxide (GO) or nano-hydroxyapatite (n-Hap) to achieve superior mechanical properties, oxidative stability, and bio-integration [25, 70–72]. These methods markedly improve UHMWPE’s wear resistance (e.g., up to 70% reduction in wear rate), biocompatibility (e.g., over 90% cell viability), hydrophilicity (e.g., contact angle decreased to ~50°), and mechanical properties (e.g., significant enhancements in hardness and tensile strength), while effectively suppressing oxidative degradation and inflammatory responses [73–77].

A schematic illustration depicting the modification of UHMWPE for biomedical applications encompassing surface modification and bulk blending-based modification.

The modification of UHMWPE represents a pivotal driver in the evolution of biomedical materials, catalyzing the development of multifunctional integrated implants, enabling patient-specific customization and intelligent design, and furnishing essential technological foundations for the next generation of high-performance, long-term medical devices. This progress carries substantial scientific and clinical relevance, positioning UHMWPE-based innovations at the forefront of advanced implantology and therapeutic outcomes. In this context, hybrid modification strategies integrating surface engineering (e.g., coatings, chemical grafting, laser processing, plasma activation) and bulk blending techniques (e.g., organic/inorganic composites) have emerged as an essential research direction to functionally enhance UHMWPE. These approaches aim to synergistically improve the material bioactivity, mechanical performance, and long-term stability. This review systematically summarizes recent advancements in these modification strategies, critically examines their efficacy in enhancing implant performance, and discusses the persistent challenges in balancing property trade-offs, ensuring long-term biosafety, and achieving clinical translation. It is intended to provide comprehensive insights and a clear direction for the development of novel UHMWPE-based implant materials that combine superior mechanical properties, robust bio-integration capability, and extended service life.

Surface engineering strategies are pivotal in tailoring the surface properties of UHMWPE without compromising its bulk mechanical integrity [13]. Techniques such as plasma treatment can effectively introduce polar functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine) onto the polymer surface, markedly improving its surface energy and wettability [78, 79]. This enhanced hydrophilicity promotes protein adsorption, cell adhesion, and spreading, which are crucial for tissue integration. Chemical grafting, including the covalent immobilization of bioactive molecules such as collagen and peptides, can transform the bio-inert UHMWPE surface into a bioactive interface, actively encouraging specific cellular interactions and bone bonding [80, 81]. Moreover, physical methods like laser surface texturing can create controlled micro- or nano-scale topographies that influence cell behavior and, in tribological applications, serve as reservoirs for lubricants to further reduce wear [82–84]. Additionally, the application of thin-film coatings, such as DLC or functionalized polymer layers, can directly augment surface hardness, reduce friction, and provide a robust platform for subsequent bio-functionalization [85–87].

Surface coating is critically important for developing next-generation UHMWPE implants with enhanced bioactivity and longevity [25, 88–90]. Considering that inherent surface inertness and lack of inherent antibacterial functionality of UHMWPE pose significant risks of surgical site infections, limiting their clinical utility, a novel one-pot coating strategy was developed by Lv et al. [91] to functionalize UHMWPE sutures with a composite layer comprising catechol (CA), tobramycin (Tob), and poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (pSBMA). UHMWPE fibers were ultrasonicated in ethanol (200 W, 30 min), rinsed with water, and dried at 60°C. UHMWPE fibers modified with CA and Tob (UCT) sutures were prepared by immersing pretreated fibers in a CA/Tob solution and stirring for 36 h at room temperature; UCT modified with pSBMA (UCTS) sutures were made similarly with 0.0125 mM sulfobetaine methacrylate (SBMA) added. This facile approach resulted in a uniform coating that significantly reduced surface roughness while maintaining excellent mechanical performance, with a retention rate of breaking strength exceeding 90%. The modified sutures demonstrated remarkable antibacterial efficacy, achieving over 90% reduction against both Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), along with a 60% decrease in bacterial adhesion. Furthermore, the coated sutures exhibited outstanding biocompatibility profiles, demonstrating a hemolysis rate below 2% and supporting over 95% viability of MG-63 osteoblast-like cells. This coating technology effectively improved the longstanding issue of inadequate antibacterial properties in UHMWPE sutures, offering a straightforward modification method that enhanced procedural safety. Although demonstrating considerable translational potential, the study lacked in vivo infection models. Further implantation studies are essential to comprehensively evaluate its long-term anti-infective efficacy and biological integration under physiological conditions.

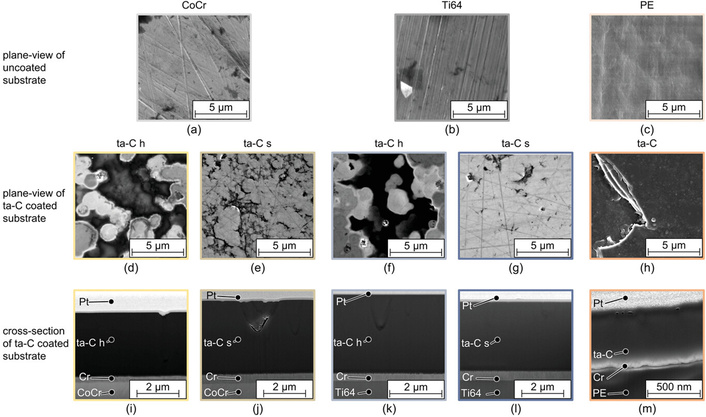

Despite the significant potential of tetrahedral amorphous carbon (ta-C) coatings in enhancing the wear resistance of orthopedic implants [92], their biocompatibility, mechanical characteristics (e.g., hardness and adhesion), and fundamental wear mechanisms on biomedical substrates like CoCr, Ti64 alloys, and UHMWPE are not yet fully understood. Rothammer et al. [93] deposited ta-C coatings on CoCr, Ti64, and UHMWPE via plasma-filtered pulsed laser-arc PVD (DREVA 600 system), with ~100 nm (CoCr/Ti64) or ~50 nm (UHMWPE) Cr adhesion layers (Figure 2). Experimental results revealed that the hardness of the ta-C coating is 6.5–12.8 times greater than that of the CoCr substrate, 8.0–12.8 times higher than Ti64, and exceeds 350 times that of the UHMWPE matrix. In tribological tests, the wear rate of UHMWPE decreased by 48% when articulated against ta-C-coated CoCr and by 73% against coated Ti64, while the wear rate of the metal counterface was reduced by 20 to 116 times. The coated surfaces showed improved hydrophilicity, indicated by a lower contact angle and higher surface energy, and demonstrated excellent cytocompatibility with MG-63 cell viability exceeding 90%. Additionally, analysis of wear tracks identified two main failure mechanisms, i.e., thermally induced depressions originating from the coating process and near-surface fatigue damage under tribological loading. These findings underscored the ability of ta-C coatings to substantially extend the service life of artificial joints and mitigate osteolysis risk by minimizing wear debris release, thereby offering a promising surface modification strategy for load-bearing implants.

Plane-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs of the (a–c) uncoated substrate surfaces, (d–h) the ta-C layers, and (i–m) focused ion beam (FIB) cross-sections of CoCr:ta-C h, CoCr:ta-C s, Ti64:ta-C h, Ti64:ta-C s, and PE:ta-C. Reprinted from [93]. © 2023 The Authors. Licensed under a CC-BY 4.0.

The long-term clinical success of prosthetic implants is critically dependent on the comprehensive performance of biomaterials. Various surface modification strategies, such as porous structuring, surface texturing, and coating deposition, have shown potential to address these limitations; however, a systematic integration and comparison of their effects on the tribological and biological properties of UHMWPE-based pairs remain necessary. Shah et al. [94] indicated that porous cobalt-chromium (CoCr)-coated prostheses achieve a 10-year total hip arthroplasty survival rate of 80%–98%, while laser-formed dimple textures reduce the UHMWPE wear rate by 36.8%. DLC coatings further enhance the wear resistance of CoCr substrates, lowering the friction coefficient against UHMWPE to approximately 0.15. Beyond mechanical and tribological improvements, electrical measurements have been established as a reliable method to assess process reproducibility, as demonstrated by a resistivity deviation below 5% in solvent-mixed UHMWPE/cellulose nanocrystal composites. This work systematically evaluated multiple modification pathways and identified optimal solutions (such as dimple texturing and DLC coating) to extend implant service life and reduce the incidence of revision surgeries.

Ti6Al4V alloy is widely used in orthopedic implants due to its excellent mechanical properties and osseointegration ability, yet its poor wear resistance and susceptibility to corrosion by biological fluids often lead to implant failure. UHMWPE is biocompatible but forms porous single coatings, while octadecylphosphonic acid (ODPA) can act as an anti-corrosion barrier; however, research on the corrosion protection of Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE/ODPA bilayer coatings and optimization of dip-coating parameters remains insufficient. Anaya-Garza et al. [95] fabricated Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE/ODPA coatings via the dip-coating technique. Ti6Al4V samples were ground with 400–1,500 grit emery papers, ultrasonically cleaned in distilled water/ethanol/acetone, and dried. They prepared 5 wt% UHMWPE/decalin and 1 mM ODPA/ethanol solutions, then fabricated single-layer coatings (Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE: 20–40 s immersion; Ti6Al4V/ODPA: 12–48 h immersion) and bilayer coatings (40 s UHMWPE + 30 h ODPA). The study identified optimal single-layer parameters: Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE dip-coated for 40 s (corrosion current density 1.51 × 10–9 A·cm–2, corrosion protection efficiency 99.9%) and Ti6Al4V/ODPA for 30 h (corrosion current density 6.8 × 10–8 A·cm–2, corrosion protection efficiency 97.2%). The bilayer coating (40 s UHMWPE + 30 h ODPA) reduced roughness from 19.34 nm to 12.67 nm, achieved a corrosion rate of 7.46 × 10–4 μm·y–1 and 99.99% corrosion protection efficiency, and shifted the contact angle from 94.1° (hydrophobic) to 51.0° (hydrophilic, beneficial for cell adhesion). The Ti6Al4V/UHMWPE/ODPA bilayer coating via low-cost dip-coating improved corrosion resistance and hydrophilicity, addressing Ti6Al4V’s drawbacks, yet its in vivo biocompatibility and tribological properties require further verification for clinical application.

Although metals such as Ti, Zr, and Ta exhibit excellent biocompatibility and wear resistance, their deposition as thin-film coatings on UHMWPE via magnetron sputtering and the resulting interfacial properties have not been systematically investigated. Rodrigues et al. [96] deposited Ti, Zr, and Ta thin films on UHMWPE via direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering. First, UHMWPE was cut into 1.75 mm × 1.75 mm pieces and ultrasonically cleaned. Deposition was under 4 × 10–7 mbar base pressure with Ar as working gas (Ti: 100 W, 7 min; Zr: 100 W; Ta: 93 W). Uniform metallic coatings with thicknesses ranging from 288 nm (Ti–PE) to 440 nm (Zr–PE) were successfully prepared, significantly enhancing surface wettability, as evidenced by the reduction in water contact angle from 102° for pure UHMWPE to 55°, 50°, and 80° for Ti–PE, Zr–PE, and Ta–PE, respectively. Coating adhesion exceeded 96 MPa in pull-off tests with no delamination observed in nanoscratch experiments, while Rutherford backscattering spectrometry confirmed the high purity of the deposited layers. Mechanical characterization revealed a notable increase in hardness, with Ti–PE reaching 0.085 GPa compared to 0.060 GPa for unmodified UHMWPE. In electrochemical tests, Ta–PE exhibited the best corrosion performance, featuring the highest corrosion potential (–169 mV) and the lowest current density, followed by Ti–PE and Zr–PE. These results established magnetron sputtering as a viable surface modification strategy for UHMWPE, effectively mitigating wear and improving interfacial properties to extend prosthesis longevity and reduce inflammation risks.

Nylon (polyamide) boasts excellent biocompatibility, while its potential as a bioactive coating for UHMWPE substrates remains underexplored. Hassanein et al. [97] prepared nylon 6,6 coated UHMWPE by dissolving nylon pellets in anhydrous methanol and ethanol with calcium chloride, applying heat treatment, and immersing UHMWPE fibers. A nylon 6,6-coated UHMWPE substrate demonstrated a 56% higher 24-hour antibacterial rate against E. coli compared to the uncoated control, along with a 4–5 fold reduction in viable S. aureus counts (5.5 × 107 CFU·mL–1 vs. 2.8 × 108 CFU·mL–1). The coated material also promoted wound closure, achieving 80% coverage versus 60% for uncoated UHMWPE, while reducing simulated body fluid (SBF) absorption to 22.8%, significantly lower than the 42.7% observed in the control. Alizarin Red staining further confirmed the absence of bone mineralization, indicating that the coating met the non-osteoinductive requirement for certain biomedical applications. These findings established a feasible coating process for UHMWPE that effectively addressed its inherent deficiencies in antibacterial and wound-healing performance, yet their long-term in vivo stability and interfacial adhesion require further validation.

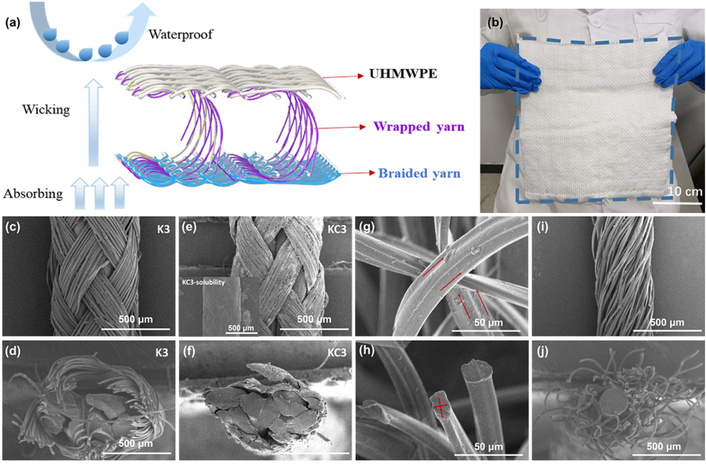

Despite the inherent waterproof characteristics of UHMWPE, its application in advanced hemostatic dressings is underexplored. A composite dressing architecture integrating a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)/carboxymethylated viscose contact layer, a nylon/Coolmax spacer layer, and a UHMWPE waterproof layer holds potential to overcome the common limitations of current dressings, such as insufficient liquid absorption and poor compression recovery. Nevertheless, a comprehensive evaluation of its performance and the development of routes for its large-scale preparation are still lacking. Zhang et al. [98] focused on the structure, preparation, and properties of PTFE/carboxymethylated viscose braided yarns and nylon monofilament/Coolmax wrapped yarns. The braided yarns were prepared using a high-speed braiding machine at a rotation speed of 1,000 r·min–1, with the pitch adjusted to 2–4 mm. After carboxymethylation (KC series), the structure shrank, and the shell layer wrapped the core yarn after dissolution, as demonstrated by the SEM results (Figure 3). The results suggested that the structural and performance differences between K3 (unmodified PTFE/viscose braided yarn, pitch 3 mm) and KC3 (carboxymethylated counterpart). SEM images revealed that K3 maintains a loose braided structure in longitudinal and cross-sectional views, while KC3 shrank after carboxymethylation, with the carboxymethylated viscose shell wrapping the PTFE core upon dissolution. K3, as part of the unmodified group, has lower tensile breaking strength and stripping resistance than KC3, as carboxymethylation enhances yarn viscosity and core-shell friction. KC3 avoided core leakage issues observed in K3 with larger pitch, though KC2 (pitch 2 mm) outperforms KC3 in mechanical properties (tensile strength 79.67 ± 0.16 N, stripping resistance 3.8 ± 0.05 N). Therefore, Coolmax featured a four-groove cross-section and longitudinal protruding structures, which could form liquid conduction channels and improve the efficiency of moisture absorption and evaporation. Overall, the optimized yarn structures and parameters laid a foundation for the composite hemostatic dressing’s performance, yet comprehensive property evaluation and scalable preparation routes still need to be developed.

Structural characterization of the spacer dressing and its constituent yarns. (a) 3D simulation image of spacer dressing, including raw material and function description. (b) The actual image of the spacer dressing. SEM images of braided yarn K3, including longitudinal image (c) and cross-section image (d). SEM images of braided yarn KC3, including longitudinal image (e) and cross-section image (f), KC3-solubility was the braided yarn immersed in water for 30 s and dried. SEM images of Coolmax (75 denier/100F polyester filament), including longitudinal image (g) and cross-section image (h). SEM images of wrapped yarn, including longitudinal image (i) and cross-section image (j). Adapted from [98]. © 2023 The Author(s). Licensed under a CC-BY 4.0.

Notably, chemical grafting-based surface modification has emerged as a crucial strategy for enhancing UHMWPE biological compatibility and durability [99–101]. This covalent functionalization strategy introduces specific functional groups or bioactive molecules onto the UHMWPE polymer chains [102]. Such surface engineering enhances hydrophilicity for improved cell adhesion and enables the immobilization of bioactive agents to promote osseointegration in acetabular components [103–105]. Consequently, chemical grafting is pivotal for developing advanced UHMWPE implants with superior biological activity and interfacial properties.

In order to address the critical limitation of poor fiber-matrix interfacial bonding in fiber-reinforced hydrogel composites for soft tissue replacement, specifically the extremely poor adhesion between inherently hydrophobic UHMWPE fibers and PVA hydrogel, with an initial interfacial shear strength of only 11.5 ± 2.9 kPa, Holloway et al. [106] employed a technical method involving oxygen plasma treatment (1 W·cm–2, 0–9 min) to activate the fiber surfaces generating oxygen-containing functional groups, followed by covalent grafting of PVA using glutaraldehyde (5–20 wt%) as a crosslinker. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis confirmed the oxygen-to-carbon ratio increased from 0.08 to 0.4 after plasma treatment, and the C–O bond proportion increased from 8.3% to 20.2%; after grafting, the C–O bond proportion further increased to 36.3%. Single fiber pull-out tests demonstrated that plasma treatment alone (6 minutes) increased the interfacial shear strength to 27.4 ± 5.0 kPa, while PVA-grafted samples treated with 20 wt% glutaraldehyde for 6 hours achieved 228.6 ± 77.1 kPa, representing an approximately 20-fold improvement. Under optimized conditions (10–20 wt% glutaraldehyde, 2–6 hours), fiber tensile failure (strength approximately 2–3 GPa) occurred, indicating the interfacial strength exceeded that of the fiber. That study established a reliable covalent interface bonding strategy, enhancing the interfacial shear strength of UHMWPE/PVA composites from a baseline of 11.5 kPa to 228.6 kPa, thereby providing an effective technical pathway and theoretical basis for resolving the long-standing challenge of poor interfacial compatibility of biomedical UHMWPE fibers in soft tissue composite materials. However, further validation under physiological conditions and long-term performance evaluation remains necessary to assess its practical applicability in soft tissue implants.

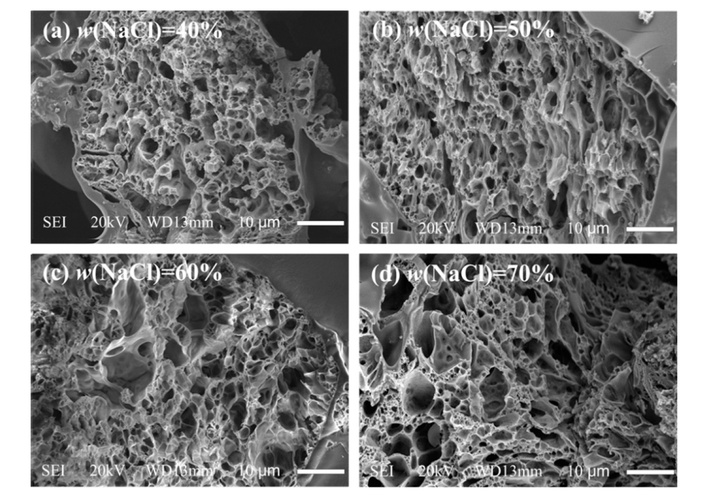

Notably, functionalized activated nanocarbon (FANC), graft-modified with polyethylene-grafted maleic anhydride (PE-g-MAH), has shown potential to simultaneously enhance UHMWPE’s hydrophilicity and the compromised mechanical integrity that results from the essential porosification process; however, research on porous FANC/UHMWPE composites remained insufficient. Fan et al. [107] first prepared acid-treated activated nanocarbon (ATANC) via ANC etching with H2SO4/HNO3 (1:3 v/v), then grafted PE-g-MAH onto ATANC to obtain FANC12.5 (optimal PE-g-MAH/ATANC mass ratio 12.5:1) (Figure 4). They dispersed UHMWPE powder and FANC12.5 in decalin, ball-milled, dried, mixed with NaCl (pore-forming agent), hot-pressed (10 MPa/25°C for 10 min, 180°C for 20 min), dissolved NaCl in water, and dried. The study found that the porous composite prepared with 3 wt% FANC and 60 wt% NaCl (as pore-forming agent) exhibited a porosity of 38.4% and a tensile strength of 14.3 MPa (28% higher than that of porous UHMWPE without FANC). Meanwhile, the material’s water contact angle decreased from 87° (pure UHMWPE) to 57° (~34% reduction), indicating improved hydrophilicity. In vitro tests showed the survival rate of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (3T3) after 5-day culture on the composite was 35% higher than that on porous UHMWPE. Herein, this work resolved the hydrophilicity-mechanical properties contradiction of porous UHMWPE, qualifying it as a viable cartilage replacement material and providing a candidate for articular cartilage repair. While 3 wt% FANC + 60 wt% NaCl has been identified as the optimal formulation for achieving a balanced porous structure, hydrophilicity, and mechanical properties in modified UHMWPE, its potential for cartilage repair remains to be fully validated. Further research should assess its long-term fatigue resistance and biological response in vivo to confirm its practical applicability.

SEM images of the texture of porous UHMWPE/FANC12.5 specimens with a 3% weight content of FANC12.5. (a) UHMWPE/FANC12.5 (FANC12.5 3%, NaCl 40%), (b) UHMWPE/FANC12.5 (FANC12.5 3%, NaCl 50%), (c) UHMWPE/FANC12.5 (FANC12.5 3%, NaCl 60%), (d) UHMWPE/FANC12.5 (FANC12.5 3%, NaCl 70%). Reprinted from [107]. © 2021 by authors. Licensed under a CC-BY 4.0.

Laser surface treatment emerges as a vital technology to address the limitations of UHMWPE materials. This non-contact, precise method can create controlled micro-topographies on the UHMWPE surface, enhancing protein adsorption and cellular response for improved biointegration. Furthermore, laser-induced surface patterns can serve as micro-reservoirs for lubricants, significantly reducing friction and wear. This surface engineering approach is therefore essential for augmenting the biological and tribological performance of UHMWPE implants.

In metal-on-polyethylene (MoP) joint replacements, CoCr alloys articulate against UHMWPE, and the wear debris generated from UHMWPE can lead to osteolysis and eventual implant loosening. Laser surface texturing using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser presents a promising approach to enhance tribological performance by modifying surface topography and lubrication regimes. Alvarez-Vera et al. [108] created four laser surface texturing patterns (line, net, dimple, surface) on CoCr alloy discs using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. The tribological performance was evaluated using a pin-on-disc tribometer under lubricated conditions, measuring the coefficient of friction and wear of UHMWPE pins articulating against the discs. This work demonstrated that laser surface texturing significantly refined the grain size of secondary phases in the CoCr subsurface region, with an average grain size of 8.2 ± 0.98 μm observed within the 100 μm surface layer, compared to 56.5 ± 10.1 μm in the untreated matrix. Correspondingly, the nanohardness increased from 2.83 GPa to 4.45 ± 0.16 GPa. All textured patterns, including line, net, dimple, and surface types, reduced the friction coefficient, with the dimple texture yielding the most substantial reduction in UHMWPE wear rate, 35% lower than that of the untextured pair. This improvement was attributed to a transition in the lubrication regime from boundary to elastohydrodynamic conditions, evidenced by a stable friction coefficient with increasing Hersey number. The study identified optimal laser surface texturing parameters (e.g., 2 mm·s–1 scanning speed and 6,000 W laser power for dimple fabrication) to enhance the tribological properties of CoCr–UHMWPE pairs, thereby extending artificial joint longevity and mitigating loosening risks. Consequently, the study demonstrated that laser surface texturing, particularly dimple patterns, can reduce UHMWPE wear by improving lubrication, though its long-term clinical efficacy requires further in vivo validation.

Notably, the surface characteristics of UHMWPE like roughness and wettability, directly influence cell adhesion and bone bonding quality. Riveiro et al. [109] focused on optimizing UHMWPE surface properties to improve biological response, with existing studies indicating that surface roughness around 1 μm enhances bone bonding, and laser treatment served as a surface modification method that can adjust material properties via thermal or photochemical effects. Technically, the study employed a diode end-pumped Nd:YVO4 laser at wavelengths of 1,064 nm, 532 nm, and 355 nm to treat carbon-coated UHMWPE samples, utilizing a full factorial design of experiments to analyze the effects of laser power, pulse frequency, scanning speed, and spot overlapping on average roughness and contact angle. The research findings revealed the increased surface amorphization post-laser treatment, specifically shown by decreased intensity at 1,415 cm–1 and increased intensity at 1,440 cm–1; roughness analysis identified laser power and scanning speed as key factors, with average roughness reduced from the original 2.3 ± 0.4 μm to 1.7 ± 0.5 μm for 532 nm and 1.9 ± 0.6 μm for 355 nm treatments. Contact angle measurements demonstrated improved wettability, with the original contact angle of 82° ± 5° decreasing to 57.6° ± 6° for 532 nm and 56.8° ± 7° for 355 nm treatments. Besides, SEM observations showed that 1,064 nm treatment leads to microcrack formation, while 532 and 355 nm treatments caused surface melting and carbon particle trapping, affecting topography. Therefore, the study demonstrated that 532 nm and 355 nm laser treatments effectively optimize UHMWPE surface properties for orthopedic implants by achieving a favorable surface roughness near 1 μm and significantly enhancing wettability. The improved wettability, particularly from UV laser treatment, is attributed to residual carbon particles acting as surfactants, thereby offering a controllable means to enhance implant-cell interactions and osseointegration.

To investigate the effect of different laser conditions and parameters on the fabrication of square/rectangular bulge textures on UHMWPE surface, and compare the tribological performance of textured and untextured samples, Hussain et al. [110] prepared UHMWPE disks with radius 15 mm and thickness 5 mm, polished with 240–1,200 grit sandpapers (150–300 rpm), cleaned with acetone, and the surface roughness was controlled at 0.1–0.15 ± 0.004 μm; a QC-F20 laser machine was used for texturing under four conditions (room temperature, freezing temperature, distilled water layer, aluminum foil coverage) by adjusting over-scan times (1–4), scanning speed (25–40 mm·s–1), and laser intensity (20–35 MHz). Research indicated that target textures could only be fabricated under aluminum foil coverage, with the optimal parameters of 2 over-scan times, 25 mm·s–1 scanning speed, and 30 MHz laser intensity; the square texture had a bulge width of 500 μm, groove width of 200 μm, and depth of 110 μm, while the rectangular texture had a bulge width of 400 μm, length of 600 μm, groove width of 250 μm, and depth of 120 μm; the COF of textured samples was significantly lower than that of untextured ones, with the most obvious difference under 2 N load and 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) concentration, and the wear track depth (12 μm) was 29.4% lower than that of untextured samples (17 μm). That study addressed the challenging texturing of UHMWPE caused by its high melt viscosity by establishing reproducible laser processing parameters. By establishing reproducible laser processing parameters, this work resolved the texturing challenge posed by the high melt viscosity of UHMWPE. The developed technique significantly enhanced the tribological performance of implants by reducing wear debris generation, thereby extending potential service life. While these findings offered a promising and practical surface modification strategy, further validation of long-term durability and biocompatibility in physiological environments remains essential to confirm its substantial clinical benefits.

Plasma surface treatment has emerged as a critical technology to expand the application potential of materials [111–113]. As a dry, solvent-free process, it effectively modifies surface properties without altering the material bulk characteristics. Plasma treatment introduces polar functional groups and creates micro-roughness, significantly enhancing surface energy and hydrophilicity [63, 114, 115]. This promotes superior protein adsorption, osteoblast adhesion, and bone integration. Furthermore, the activated surface serves as an ideal platform for subsequent covalent grafting of bioactive molecules, making plasma treatment indispensable for developing advanced, long-lasting UHMWPE implants.

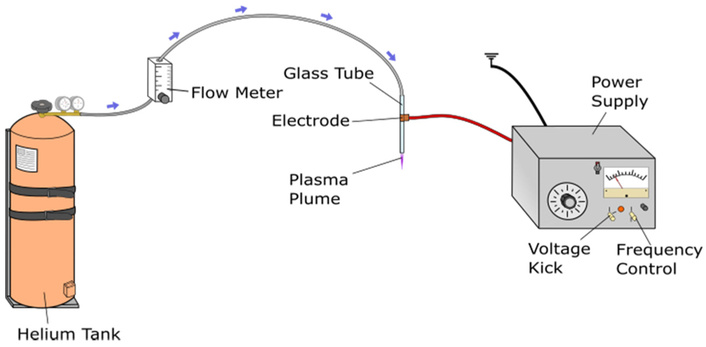

To address the dilemma that UHMWPE wear debris can trigger immune responses, which in turn lead to prosthesis loosening, Turicek et al. [116] used UHMWPE with a MW of ~6 × 106 g·mol–1 to prepare different modified UHMWPE samples (13 mm diameter, 3 mm thickness). After polishing and ultrasonic cleaning, samples were treated with helium tubular CAP plasma, with various gas flow rates, treatment positions (plume base/tip), and different durations (Figure 5). The contact angle decreased from the initial 79° to 27–29° (32–54% reduction), with optimal effects at 2.5 L·min–1 for base/tip treatment; roughness increased from 4.83 nm to a maximum of 48 nm (10-fold increase), significantly influenced by gas flow rate. Besides, hardness showed no significant change, with the initial peak hardness of 68.7 Shore-D and post-treatment hardness of 69–70.5 Shore-D, and a 1-minute short plasma treatment significantly reduced the water contact angle while inducing only minimal surface roughness increase. Notably, the material met ISO 10993 biocompatibility standards, with no cytotoxicity, and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell adhesion rate increased by 20–30%. Therefore, the CAP plasma modification process was established without altering bulk properties, significantly improving wettability and adhesion, enhancing interaction with synovial fluid, and reducing wear risk. The short-treatment scheme could balance lubrication and wear resistance, thus providing an effective technical path to extend joint prosthesis lifespan with important clinical application value.

Schematic of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) source used for the treatment of the UHMWPE samples. Reprinted from [116]. © 2021 by authors. Licensed under a CC-BY 4.0.

Notably, the high incidence of glenoid component loosening in UHMWPE-based shoulder prostheses stems from the intrinsically inert and non-polar nature of UHMWPE, which severely limits its adhesive bonding with PMMA bone cement. Conventional surface modification techniques offer limited efficacy, motivating the exploration of atmospheric pressure dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma treatment as a promising alternative. Cools et al. [117] performed plasma activation on UHMWPE samples using a medium-pressure DBD with helium, air, argon, and nitrogen gases. They subsequently conducted atmospheric-pressure plasma polymerization of methyl methacrylate onto the pre-activated substrates using a helium DBD. That study demonstrated that helium-atmosphere DBD plasma activation effectively enhanced UHMWPE surface hydrophilicity, reducing the water contact angle from 93° to 43°–62°, with the most pronounced reduction achieved using nitrogen plasma. XPS confirmed the incorporation of polar oxygen-containing functional groups, including C–O (5.9–8.3%) and C=O (0.9–2.3%) species. Subsequent plasma polymerization of methyl methacrylate under optimized conditions yielded uniform PMMA-like coatings with an O/C ratio of 0.22–0.25. The coatings exhibited excellent stability in physiological environments, showing only minor ester bond hydrolysis after 14 days in PBS, and maintain outstanding hemocompatibility with a hemolysis rate below 5%. Overall, a scalable, plasma-based modification strategy that directly addressed the critical issue of UHMWPE-PMMA adhesion in joint arthroplasty was established, offering a viable pathway to reduce implant loosening. While the resulting coatings demonstrated satisfactory stability and biocompatibility, their long-term wear performance and osseointegration require further in vivo validation to fully confirm clinical applicability.

Blending modification plays a pivotal role in advancing the modification of engineering plastic, including UHMWPE for biomedical applications [118, 119]. For example, it effectively alleviates the significant manufacturing challenge posed by UHMWPE’s extremely high melt viscosity that restricts processability via conventional methods such as injection molding and may compromise the consolidation quality of final products. Furthermore, blending modification addresses the poor integration with bone tissue for non-bearing implant components, a limitation arising from UHMWPE’s bio-inertness despite its advantage in minimizing adverse reactions. By resolving these critical drawbacks, blending modification substantially broadens UHMWPE’s application fields, fully unleashes its potential in the biomedical sector, and enables the material to retain its inherent merits while meeting diverse clinical requirements for implantable devices.

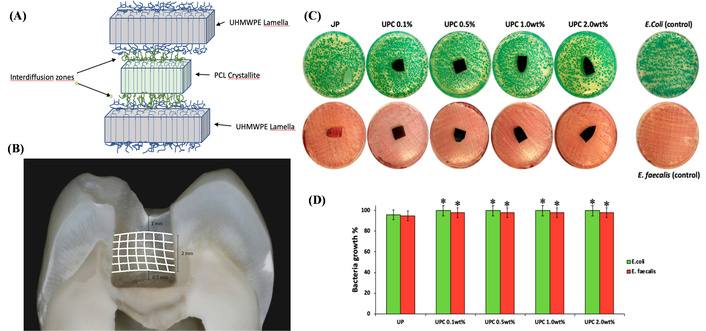

Note that HDPE can improve UHMWPE’s processability by reducing melt viscosity, while PCL provides additional biocompatibility and biodegradability, and bioglass (BG) promotes cell adhesion and osseointegration—key for implant-bone interaction. However, the thermal and mechanical properties of the quaternary UHMWPE/HDPE/PCL/BG composite system remain unstudied, creating a gap in advanced orthopedic implant material development. Espinosa et al. [120] synthesized BG via sol-gel method (TEOS, TEP, NaNO3, Ca(NO3)2·4H2O; dried at 60/200°C, sintered at 1,000°C) and prepared UHMWPE/HDPE/PCL/BG composites (two UHMWPE/HDPE ratios: 10/90, 30/70; two PCL contents: 5%, 10%; 3% BG) via twin-screw extrusion (TM 20 HT, 190/200/190°C, 125 rpm). That study found no chemical interaction between UHMWPE and PCL in the composites, indicating physical blending. PCL could crystallize between the UHMWPE lamellar structure due to its concentration and the polymeric chain size (Figure 6A). For thermal properties, PCL’s melting temperature decreased with a new thermal transition peak, and polyethylene (PE, from UHMWPE/HDPE) melting enthalpy reduced as PCL content increased. Mechanically, the composite with 30 wt% UHMWPE and 10 wt% PCL had the highest toughness. In processability, the 10 wt% PCL group’s melt flow index (MFI) was 153% higher than the 5 wt% PCL group, confirming PCL’s role in enhancing flowability; notably, 3 wt% BG had no significant effect on thermal behavior. This system improved UHMWPE’s processability issue, and its light-white appearance is close to pure UHMWPE, thus retaining biomedical application potential and providing data support for prosthetic material design.

Structural and performance characterization of organic blend-modified UHMWPE. (A) Proposed inter-diffusion of polycaprolactone (PCL) and polyethylene crystallites. Adapted with permission from [120]. © 2020 Wiley Periodicals LLC. (B) The position of the ribbond fibers on the tooth cavity walls. Adapted with permission from [121]. © 2022 Wiley Periodicals LLC. (C) Representative image of E. coli and E. faecalis incubated with all materials. (D) Bacteria growth (%) of E. coli and E. faecalis incubated with different nanocomposites. (C) and (D) adapted from [122]. © 2020 by authors. Licensed under a CC-BY 4.0.

Notably, while α-tocopherol (α-T) has been shown to effectively inhibit the oxidative degradation of UHMWPE, artificial joints in vivo are simultaneously exposed to SBF immersion and cyclic mechanical loading, and the synergistic effect of these conditions on the properties of α-T/UHMWPE remains unclear. Yang et al. [123] fabricated α-T-stabilized UHMWPE specimens by blending UHMWPE powder with an α-T acetone solution and compression molding. They immersed samples in SBF for one year and applied force with degradation using a pin-on-disk test. That study demonstrated that after one year of SBF immersion, the crystallinity of α-T/UHMWPE increased by 7.0%, accompanied by a 13.4% rise in the surface O/C ratio, while its ball indentation hardness decreased from 25.47 MPa to 21.53 MPa, reflecting a 15.5% reduction. Following subsequent cyclic loading (250 N, 2.5 × 106 cycles), the indentation depth increased by 50.4%, which was 40% lower than the decrease observed in pure UHMWPE. In terms of wear behavior, aged pure UHMWPE exhibited a combined abrasive and fatigue spalling mechanism, whereas the aged α-T/UHMWPE primarily displayed abrasive wear. Thus, the study confirmed the protective effect of α-T against UHMWPE degradation under simulated physiological conditions, though its long-term clinical performance still requires further validation through in vivo studies.

Although gamma irradiation crosslinking enhances UHMWPE’s wear resistance effectively (by 90%), it compromises mechanical properties and generates long-lived free radicals prone to persistent oxidative degradation, creating an urgent need for novel modification strategies. Conventional antioxidants such as α-T can mitigate this issue, yet often at the cost of reduced crosslinking efficiency. In this context, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a natural polyphenol containing eight phenolic hydroxyl groups, exhibits potent antioxidant capacity, though its application in UHMWPE has remained underexplored. Kang et al. [124] fabricated EGCG/UHMWPE specimens by blending UHMWPE powder with an EGCG ethanol solution, drying, and compression molding at 200°C and 15 MPa. The samples were gamma-irradiated at 100 kGy under nitrogen and accelerated aged at 70°C in 503 kPa oxygen. That study demonstrated that extracts from EGCG-blended UHMWPE showed no cytotoxicity toward L929 cells, with cell viability comparable to that of pure UHMWPE. More importantly, after gamma irradiation at 100 kGy and subsequent accelerated aging, the sample with 0.3 wt% EGCG displayed an oxidation index (OI) of only 0.26 ± 0.04, significantly lower than the value of 2.82 ± 0.12 observed in aged pure UHMWPE. While the hardness of pure UHMWPE decreases from 25.34 MPa to 17.48 MPa after aging, the 0.3 wt% EGCG-modified sample retains a hardness of 24.67 MPa. Furthermore, its wear rate became 36.8% lower than that of pure UHMWPE, accompanied by a transition in wear mechanism from a combined abrasive and fatigue wear mode to predominantly abrasive wear. The results indicated that EGCG significantly enhanced the oxidative stability of irradiated UHMWPE while preserving crosslinking efficiency, mechanical properties, and wear resistance. This suggested a potential for extending the service life of artificial joints with maintained biosafety. However, the long-term stability of EGCG under physiological conditions and its influence on other material properties require further investigation for comprehensive clinical validation.

Dental direct composite restorations frequently exhibit insufficient mechanical properties and high fracture susceptibility, restricting their clinical service life. Fiber reinforcement is a well-recognized strategy to enhance their strength; however, research on the interface bonding between UHMWPE fibers and composite resin, as well as the long-term performance of the reinforced restorations, remains inadequate. Sfeikos et al. [121] selected 120 human molars, prepared one extensive Class I occlusal cavity per tooth, and divided them into 12 groups (n = 10) based on restorative material (Filtek Z550, Beautifil II LS, Beautifil Bulk Restorative), Ribbond UHMWPE fiber use, and related technique (incremental/bulk) (Figure 6B). The study showed that UHMWPE fiber-reinforced composite resin achieved a 55% increase in flexural strength (from 85 MPa to 132 MPa) and a 60% increase in impact strength (from 2.5 kJ·m–2 to 4.0 kJ·m–2). After silane treatment of the fiber surface, the interface bonding strength rose by 40%, and the restorations maintained 85% of their initial strength after 1 year of in vitro aging. This work optimized the UHMWPE fiber reinforcement process for dental composites, extends the service life of dental restorations, and lowered the risk of restoration detachment.

Although cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) have demonstrated potential in reducing wear and polyolefin (PO) elastomer enhances processability, the biocompatibility and antibacterial properties of UHMWPE/PO/CNF nanocomposites have not been thoroughly investigated. Catauro et al. [122] prepared UHMWPE nanocomposites by ball milling medical-grade UHMWPE with paraffin oil (2.0 wt%) and carbon nanofiller (0.1–2.0 wt%), followed by compression molding at 200°C and 20 MPa. They characterized specific wear rates using a pin-on-disc tester under different lubricants, bioactivity by soaking samples in SBF, antibacterial activity against E. coli and E. faecalis, and cytotoxicity using the MTT assay on NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells (Figure 6C, D). That study revealed that the composite containing 1.0 wt% CNF achieved the lowest wear rate, measuring 2.54 × 10–6 mm3·N·m under natural lubrication—a 93.29% reduction compared to pure UHMWPE. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis indicated that CNF inhibited polymer oxidation, as evidenced by the disappearance of the carbonyl peak at 1,743 cm–1, which is prominent in pure UHMWPE. After 21 days of immersion in SBF, the 1.0 wt% CNF sample exhibited the most intense hydroxyapatite characteristic peak at 1,021 cm–1, suggesting improved biomineralization activity. While no inhibition zone against E. coli or E. faecalis was observed, the material showed no toxicity to these strains, and the viability of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts was 10.2% higher than that on pure UHMWPE. These findings not only identified 1.0 wt% CNF as the optimal composition for balancing wear resistance and biocompatibility but also positioned UHMWPE/PO/CNF as a promising candidate material for joint prostheses with the potential to mitigate prosthesis loosening risks.

Besides, Vitamin E (VE) plays a pivotal role as an antioxidant in the modification of biomedical UHMWPE by effectively scavenging free radicals generated during irradiation to inhibit oxidative degradation [125, 126]. Nakanishi et al. [127] discovered that VE not only reduced the secretion of inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) induced by wear particles, thereby lowering the risk of macrophage-mediated osteolysis, but also distributed uniformly throughout the material via blending or diffusion, demonstrating good biocompatibility both in vitro and in vivo [127]. Thus, VE stabilization effectively inhibited key inflammatory pathways by altering particle surface properties or direct biological effects. Although VE treatment did not change the wear volume, it significantly reduced the inflammatory potential of each particle. Notably, the development of cross-linked UHMWPE fundamentally addresses critical clinical challenges through advanced materials science. Kurtz et al. [128] studied the unknown effect of low-concentration VE on the oxidative stability of UHMWPE. It concluded that the minimum VE concentration required to stabilize radiation-crosslinked UHMWPE depends on irradiation conditions, and trace additions (125–500 ppm) can effectively prevent oxidative degradation while maintaining material properties. Oral et al. [129] investigated the trade-off between wear resistance and fatigue strength in radiation-crosslinked UHMWPE. It demonstrated that spatially controlling crosslink density via a VE concentration gradient yields a material with a highly crosslinked, wear-resistant surface and a low-crosslinked bulk with high fatigue strength, featuring a well-integrated gradient interface without mechanical weakness. Periprosthetic osteolysis remains a challenge in joint arthroplasty, driven by UHMWPE wear particles. Bichara et al. [130] compared VE and virgin highly cross-linked UHMWPE particles in a murine calvarial model. VE particles induced significantly less bone resorption (3% ± 1.4% vs. 12.2% ± 8%) and inflammatory tissue formation than virgin particles. The results demonstrated the reduced osteolytic potential of VE-stabilized UHMWPE wear debris in vivo.

With the surging demand for total knee arthroplasty—projected to exceed 3 million cases annually by 2030, there is an urgent need for high-performance, personalized implant materials [131, 132]. Functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes (f-SWCNT) have demonstrated potential to enhance UHMWPE’s mechanical and tribological properties, but research on fabricating customized knee prostheses via Single-Point Incremental Forming process (SPIF) using f-SWCNT/UHMWPE composites remained limited. Zavala et al. [133] prepared f-SWCNTs/UHMWPE composites (0.01/0.1 wt% f-SWCNTs) via ultrasonication (f-SWCNTs in ethanol for 20 min, then mixed with UHMWPE for another 20 min) and hydraulic pressing (150°C, 24 MPa, 15 min). They fabricated unicompartmental knee implants via SPIF (Kryle VMC 535, tool diameter 5/10 mm, Δz 0.2/0.4 mm, feed rate 3,000 mm·min–1), and evaluated biocompatibility with hFOB 1.19 cells using viability and mineralization assays. The composite with 0.1 wt% f-SWCNT exhibited a 12% higher Young’s modulus and a 65% higher ultimate tensile strength (reaching 51.2 MPa) compared to pure UHMWPE; in vitro biocompatibility tests showed > 90% survival rate of human osteoblasts (hFOB 1.19) after 14 days of culture, and Alizarin Red S staining confirmed superior mineralization ability relative to pure UHMWPE; additionally, the SPIF process successfully fabricated unicompartmental knee prostheses, with stable forming forces when using tool diameters of 5 mm and 10 mm. While f-SWCNT-reinforced UHMWPE composites exhibited enhanced mechanical properties and favorable in vitro biocompatibility, further validation of long-term wear resistance, biological safety, and clinical performance is required to assess their practical applicability in total knee arthroplasty.

While GO exhibits exceptional mechanical properties, its application in UHMWPE matrix remained rarely explored, prompting the study to investigate GO’s effect on UHMWPE properties and determine the optimal loading. Suñer et al. [134] prepared UHMWPE/GO nanocomposites (0.1–2 wt% GO) via optimized ball milling: GO was dispersed in 30 mL ethanol, mixed with UHMWPE GUR 1020, milled in a Retsch PM 100 (400 rpm, 2 h), dried at 60°C, then hot-pressed (185°C, 15 MPa) into sheets. Results showed GO improved UHMWPE’s thermal stability, mechanical properties, and wettability, with 0.5 wt% as the optimal loading. For thermal stability, all GO-added groups had higher oxidation temperature (T0), initial linear weight loss temperature (T1), final linear weight loss temperature (T2), and complete volatilization temperature (T3) than pure UHMWPE. Mechanically, the 0.5 wt% GO group saw 15% and 25% increases in Young’s modulus and fracture stress, respectively, while the 2 wt% GO group showed significant fracture toughness reduction. In wettability, the 0.1–0.5 wt% GO groups had notably decreased water contact angles, whereas the 0.7–2 wt% groups were comparable to pure UHMWPE. After gamma irradiation (75 kGy) and aging, pure UHMWPE’s fracture stress dropped by 32%, while that of the 0.5 wt% GO group only decreased by 18%. This strategy required no additional fortifiers, alleviated UHMWPE’s post-irradiation performance degradation while ensuring biocompatibility, and provided a feasible pathway for artificial joint UHMWPE modification.

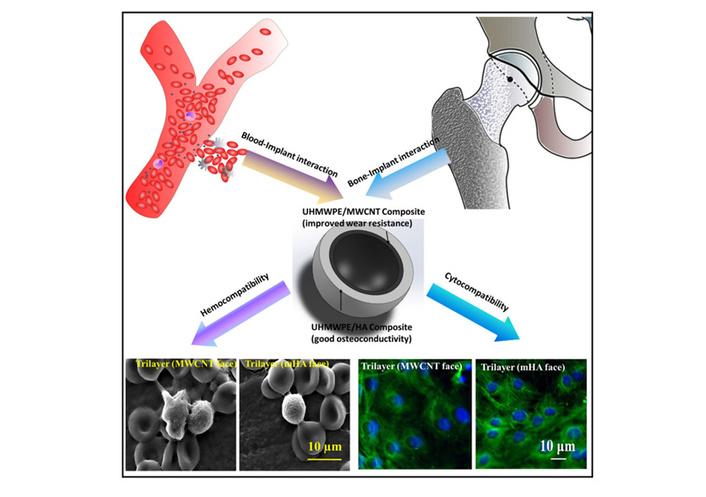

Notably, the development of orthopedic implants necessitates a synergistic balance between superior mechanical performance and favorable biocompatibility, including both cell and blood compatibility, which conventional UHMWPE alone fails to achieve. While multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are recognized for reinforcing mechanical strength and n-Hap offers osteoconductive properties, studies on their combined modification, particularly in a trilayer composite architecture (UHMWPE/MWCNT–UHMWPE–UHMWPE/n-Hap), remain scarce. Naskar et al. [135] first functionalized MWCNT by refluxing in HNO3/H2SO4 (1:3 v/v) at 140°C, synthesized n-Hap from eggshell (calcination at 900°C + H3PO4 precipitation), then mixed UHMWPE with 0.5 wt% MWCNT/6 wt% n-Hap via 45 min ball milling, and compression-molded (280/260°C, 100 kg·cm–2) into single-layer composites and trilayer ones (MWCNT/n-Hap layers + UHMWPE interlayer) (Figure 7). That study thus fabricated both monolayer and trilayer nanobiocomposites to systematically evaluate their physical and biological properties. The results demonstrated that the incorporation of 0.5 wt% MWCNT elevated the yield strength of UHMWPE from 14 MPa to 22 MPa with a 161% increase, while 6 wt% n-Hap raised it to 18 MPa, corresponding to a 122% improvement. Moreover, the trilayer composite exhibited an enhanced elastic modulus of approximately 1,500 MPa compared to its monolayer counterparts. In terms of hemocompatibility, UHMWPE/n-Hap showed a 25% reduction in hemolysis rate relative to pure UHMWPE, along with suppressed platelet activation. Protein adsorption studies revealed that the equilibrium constant (Keq) for BSA on UHMWPE/MWCNT is about 3.5 × 103 cm3·μg–1, higher than the 2.3 × 103 cm3·μg–1 observed for the n-Hap-modified group. Regarding cellular responses, the n-Hap-enriched side supported the highest 7-day survival rate of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), whereas cells on the MWCNT side displayed aligned and orderly morphology, with the trilayer configuration exhibiting cell compatibility comparable to that of monolayer systems. Overall, the trilayer design effectively integrated the mechanical reinforcement afforded by MWCNT with the bioactive benefits of n-Hap, offering a promising material strategy for orthopedic applications such as acetabular cups, where conventional materials struggle to reconcile mechanical durability with biocompatibility.

Overall concept of developing trilayer nanobiocomposite based acetabular socket. The dual requirement of physical property enhancement together with cell/blood compatibility at articulating surfaces can be addressed with UHMWPE/n-Hap layer at pelvic side and UHMWPE/MWCNT layer interfacing with femoral head. Reprinted with permission from [135]. © 2020 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Dolomite, a mineral filler with application potential, has shown promise for polymer reinforcement. Abdullah et al. [136] prepared chemically treated dolomite (ct-dolomite) by reacting dolomite with 1–3 M nitric acid and diammonium hydrogen phosphate, followed by calcination at 1,000°C. They fabricated UHMWPE composites by ball milling UHMWPE with 1–5 wt% dolomite or ct-dolomite, then hot-pressing at 190°C and 20 MPa. The research results showed that FTIR confirmed ct-dolomite powder contained carbonate (CO32–), phosphate (PO43–), and hydroxyl (OH–) groups; X-ray diffraction (XRD) indicated dolomite treated with 1 M HNO3 formed calcium hydroxide phosphate [Ca10(PO4)5(OH)] and MgO; UHMWPE/ct-dolomite composites exhibited better tensile strength than pure UHMWPE, with significantly enhanced matrix-filler interfacial interaction, while 3 wt% BG had no significant effect on the composites’ thermal behavior. This work improved UHMWPE’s insufficient mechanical properties, provided data support for designing biomedical materials (e.g., orthopedic prostheses), and expanded its application in joint implants.

Considering that the relatively insufficient mechanical strength and hardness of UHMWPE often limit the long-term stability of prostheses. Although reduced graphene oxide (rGO) exhibits exceptional mechanical reinforcement capabilities and zirconia (ZrO2) possesses recognized biocompatibility and wear resistance, a comprehensive understanding of the physicochemical properties, crystallization behavior, and biological applicability of UHMWPE composites co-filled with rGO and ZrO2 remains lacking. Singh et al. [137] employed a modified liquid-phase ultrasonication (LPU) process to disperse rGO and nano-sized zirconia (ZrO2) fillers within an UHMWPE matrix. The mixture was subsequently processed using ball milling and hydraulic hot pressing (HHP) to fabricate standard bio-nanocomposite specimens. The composite with 1 wt% rGO and 5 wt% ZrO2 was identified as the optimal formulation, exhibiting a 7.2% increase in microhardness and a crystallinity of 52.37% compared to pure UHMWPE. The tensile strength, flexural strength, and flexural modulus were enhanced by 46.76%, 37%, and 50%, respectively, while the friction coefficient and wear rate were significantly reduced. SEM confirmed the uniform dispersion of fillers and strong interfacial bonding within the composite. These results demonstrated that the hybrid rGO/ZrO2 reinforcement strategy effectively improves the mechanical and tribological performance of UHMWPE, offering a high-performance candidate material for acetabular and tibial liners in hip and knee arthroplasty, with the potential to extend implant service life and reduce the need for revision surgeries.

The development of hip joint implants necessitates that UHMWPE simultaneously fulfill adequate mechanical performance and osseointegration capacity. Although n-Hap is recognized for its osteoconductive properties, a systematic evaluation of UHMWPE reinforced with n-Hap, together with a multi-objective optimization, has not been previously undertaken. R. K. Singh et al. [138] fabricated UHMWPE/n-HAp bio-composites using heat-assisted compression molding. A grey relational analysis coupled with principal component analysis (GRA-PCA) based hybrid multi-objective optimization method was employed to determine the optimal composite composition. Experimental results indicated that the composite containing 10 wt% n-Hap exhibited an 18.75% increase in flexural strength and a 37.14% improvement in compressive strength relative to pure UHMWPE, while the maximum impact strength was achieved at 5 wt% n-Hap with a 3.38% enhancement. The GRA-PCA model identified 10 wt% n-Hap as the optimal formulation, corresponding to the lowest surface roughness, and SEM results confirmed homogeneous dispersion of n-Hap without significant agglomeration. In addition, the composite demonstrated a hemolysis rate below 5% and favorable overall biocompatibility. Overall, these findings provided valuable guidance for the design of hip prosthesis materials, enhancing bone–implant adaptability and reducing the risk of aseptic loosening, thereby offering reliable technical support for hard tissue repair applications.

Montmorillonite (MMT), a layered silicate nanofiller with a high aspect ratio and excellent mechanical strength, exhibits significant potential for reinforcing polymers; however, the mechanical properties and biocompatibility of UHMWPE composites filled with MMT have not been systematically studied, leaving a gap in optimizing UHMWPE-based implant materials. Hasan et al. [32] filled this gap and fabricated UHMWPE/MMT nanocomposites with 1–10 wt% MMT using two-roll milling and compression molding techniques, employing maleic anhydride as a compatibilizer. Biocompatibility was assessed using the MTT assay with osteoblast (MG-63) cells. The results showed that 5 wt% MMT was the optimal filling ratio: At this content, the UHMWPE composite’s compressive strength increased by 364.16% to 142.31 MPa, wear rate decreased by 53.67%, Shore D hardness rose by 26.97% to 72.5, and Izod impact strength reached 89.35 kJ·m–2 (7.34% higher than pure UHMWPE). In vitro biocompatibility tests further confirmed that the composite had an MG-63 cell survival rate > 94% without cytotoxicity. Herein, the study demonstrated that MMT nanofillers can significantly enhance the mechanical properties and in vitro biocompatibility of UHMWPE, showing potential for extending implant lifespan. However, its long-term stability, wear resistance under physiological conditions, and in vivo biocompatibility require systematic evaluation before clinical translation can be pursued.

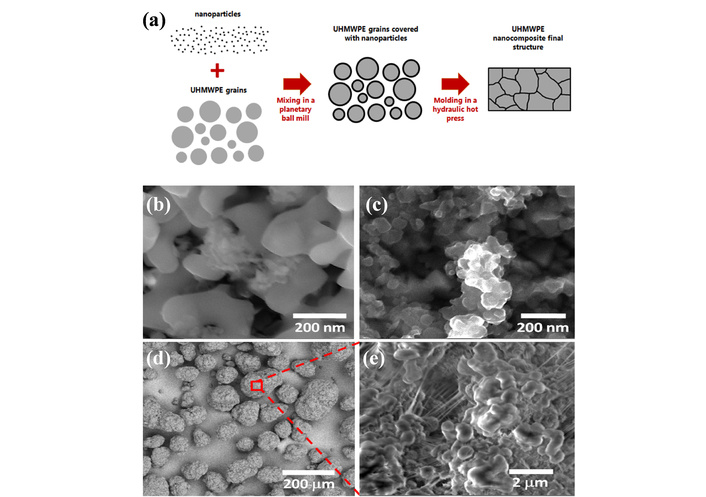

Note that UHMWPE is typically processed at temperatures approximately 70°C above its melting point, a condition that can induce thermal degradation and thus necessitates the incorporation of antioxidants (e.g., VE). The incorporation of nanofillers (e.g., alumina, Al2O3; boron carbide, B4C) has been shown to enhance the mechanical and tribological performance of UHMWPE. Nevertheless, most existing studies have centered on single-component fillers, with research regarding the synergistic effects of hybrid fillers remaining scarce. Thus, the objective is to develop UHMWPE-based single-component and hybrid nanocomposites that improve mechanical properties, reduce wear risk, and maintain thermal stability without compromise. Soares et al. [139] prepared nanocomposites by ball milling UHMWPE powder with Al2O3 and B4C nanoparticles (total 3 wt%) and VE (1 wt%), followed by hot-pressing molding (Figure 8). Herein, nanoparticles only had physical interaction with UHMWPE without molecular-level interactions between fillers and polymer, forming a three-dimensional network wrapping polymer particles, as reflected by the morphological characterization results. Thermal stability was basically maintained, only the Tonset (initial temperature of thermogravimetric analysis) of UEA [i.e., UHMWPE/VE/Al2O3 (96/1/3 wt%)] is slightly lower, and crystallinity has no significant change (pure UHMWPE, 33.03%; UEB [i.e., UHMWPE/VE/B4C (96/1/3 wt%)], 33.76%). Notably, the UHMWPE composite containing B4C exhibited significantly enhanced mechanical properties, with a Young’s modulus of 1.04 ± 0.12 GPa and a hardness of 0.078 ± 0.015 GPa. In contrast, the composite with Al2O3 showed no significant improvement. Furthermore, when used together as hybrid fillers, B4C and Al2O3 demonstrated no synergistic effect. The developed preparation protocol for mixed nanofillers successfully integrated VE to substantially suppress processing-induced oxidation, while the addition of B4C contributed to enhanced mechanical performance without sacrificing thermal stability.

Schematic of nanocomposite formation and morphology of raw powder materials. (a) Scheme of the formation of the nanocomposites structure. SEM images of the powder materials: (b) aluminum oxide; (c) boron carbide; (d) UHMWPE; (e) high magnification of a polymeric grain surface. Adapted with permission from [139]. © 2022 Wiley Periodicals LLC.

Notably, GO is a promising reinforcing nanofiller for polymer matrices, yet unmodified GO tends to agglomerate within polymer matrices due to strong van der Waals forces between its individual nanosheets, resulting in uneven improvements in material properties; thus, surface functionalization of GO through the sequential grafting of polyethyleneimine (PEI) and maleated polyethylene is proposed to enhance its dispersibility and interfacial adhesion within the HDPE/UHMWPE blend. For example, Bhusari et al. [140] synthesized maleated polyethylene-grafted modified graphene oxide (mGO) via PEI functionalization and EDC/NHS coupling. They fabricated HDPE/UHMWPE/mGO nanocomposites using melt-extrusion and injection molding. The research findings demonstrated that reinforcing the HDPE/UHMWPE blend with 1 wt% mGO remarkably enhanced mechanical performance, i.e., ultimate tensile strength increased by 120% to 65 MPa, and elastic modulus increased by 40% to 908 MPa; Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and X-ray micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) confirmed uniform dispersion of mGO (50–100 nm) within the blend, while unmodified GO formed large agglomerates (~2 μm); in vitro cytocompatibility assays using C2C12 murine myoblast cells showed a cell survival rate exceeding 90% after 3 days of culture, with no significant difference from the control group. This modified blend system could effectively balance three core requirements for biomedical UHMWPE-based materials, i.e., improved processability, enhanced mechanical properties, and favorable cytocompatibility, thus providing a promising candidate for bone tissue engineering implants (e.g., artificial joints) and advancing the application of carbon-based nanocomposites in the biomedical field.

The modification technologies for biomedical UHMWPE face a series of formidable scientific and technical challenges on the path towards next-generation high-performance implants. Firstly, the interaction mechanisms at the material-bone tissue interface are not fully understood. For instance, the underlying biomechanical mechanisms of stress-shielding-induced bone atrophy require further exploration, which limits the long-term biological fixation of implants. Secondly, achieving a balance between different performance metrics during the pursuit of multifunctionality presents a core dilemma. For example, incorporating highly effective antibacterial properties (e.g., with high active agent loading > 5 wt%) often compromises mechanical properties, potentially leading to a reduction in toughness exceeding 30%, severely impacting the structural integrity of load-bearing implants. Thirdly, the long-term biosafety of wear particles, particularly sub-micron particles (< 1 μm), remains a contentious issue. These particles may persistently activate macrophages, triggering a chronic inflammatory cascade that ultimately leads to osteolysis and aseptic loosening; the molecular and cellular mechanisms of this process need elucidation. From a technical perspective, synergistic and antagonistic effects exist between current modification methods. The complex interplay between, for example, radiation crosslinking and antioxidant stabilization, affects the final comprehensive performance of the material. The long-term structural stability, functional durability, and interfacial bond strength of modified layers under complex in vivo physiological conditions (e.g., dynamic loading, enzymatic degradation, oxidative stress) also pose significant challenges. Furthermore, transitioning from the laboratory to clinical application necessitates ensuring process reproducibility, batch-to-batch consistency, and cost control in large-scale manufacturing, which are essential hurdles to overcome for industrial application. These interconnected challenges collectively form the key bottlenecks hindering the further performance enhancement and expanded clinical application of UHMWPE materials.

Looking ahead, research and development in UHMWPE modification technology are poised to evolve towards deeper integration, intelligent functionality, and personalized customization. However, several persistent and specific challenges must be rigorously addressed to enable successful clinical translation. A primary obstacle is the limited progression to clinical trials over the past decade, largely due to translational barriers such as long-term concerns over wear debris bioactivity, potential antioxidant leaching, and the inherent compromise between wear resistance and toughness. For instance, cross-linking or incorporating reinforcing fillers often enhances wear resistance at the measurable expense of impact strength or elongation at break, creating a classic engineering trade-off. Furthermore, caution is warranted regarding osteolytic potential; in vitro studies suggest that sub-micron wear particles generated by highly cross-linked or nano-filled UHMWPE can elicit adverse biological responses, underscoring the need for thorough long-term biosafety evaluation. Scalability also presents a significant hurdle, as many advanced surface treatments (e.g., filtered cathodic arc ta-C deposition, magnetron sputtering) are line-of-sight processes ill-suited for the uniform, cost-effective coating of complex-shaped joint components in industrial manufacturing.

To overcome these challenges and realize the next generation of implants, future research must pursue several key directions. The first is true multifunctional integration. Efforts will focus on constructing synergistic composite systems—for example, by co-grafting osteoconductive hydroxyapatite with contact-killing antimicrobial peptides alongside lubricating polymer brushes—to create intelligent bio-interfaces with combined osteogenic, antibacterial, and tribological properties. Secondly, intelligently responsive design represents a disruptive avenue. Employing smart polymers sensitive to physiological cues (e.g., pH, enzymes) in molecular designs could enable the on-demand, localized release of therapeutic agents (e.g., antibiotics, growth factors) in specific pathological microenvironments, thereby enhancing treatment precision and efficacy. Thirdly, personalized customization remains a pivotal clinical goal. Integrating medical imaging, computer-aided design, and additive manufacturing (3D printing) with advanced UHMWPE-based composites [e.g., UHMWPE/PEEK (polyetheretherketone) blends] will facilitate the fabrication of patient-specific implants that match individual anatomy and bone mechanics in macro-shape, micro-architecture, and mechanical properties. Concurrently, the development of advanced computational models leveraging multi-physics coupling and artificial intelligence that incorporates factors such as biological fluid chemistry, dynamic loading, and material aging, will provide powerful tools for predicting in vivo wear and long-term performance. Ultimately, the clinical translation of these innovations will depend on systematic validation through rigorous long-term in vivo studies and clinical trials, driving the transformative advancement of UHMWPE-based implants toward extended longevity, reduced revision rates, and improved patient outcomes.

The biomedical landscape is witnessing the rapidly expanding footprint of UHMWPE, driven by its unique combination of properties. This review systematically examines the biomedical applications of UHMWPE and its corresponding modification strategies, with a focus on surface engineering and bulk modification techniques. Surface modification approaches, such as functional coatings, chemical grafting of bioactive molecules, laser surface texturing, and plasma treatment, have proven effective in enhancing surface bioactivity, improving tribological performance, and strengthening interfacial compatibility. In parallel, bulk modification via polymer blending, inorganic nanocomposite formation, and nanofiller reinforcement has substantially improved the material’s processability, mechanical properties, and biological functionality. Despite these advances, several challenges persist, including balancing multifunctional requirements, ensuring the long-term biosafety of wear debris, maintaining modification stability under physiological conditions, and achieving consistent industrial-scale production. Future research should prioritize the development of smart implants with adaptive functionalities, integrate medical imaging and 3D printing for patient-specific design, and validate clinical performance through computational modeling and long-term in vivo studies. Such coordinated efforts are crucial for driving transformative progress in UHMWPE-based implants, ultimately extending their service life, reducing revision surgeries, and improving clinical outcomes and patient quality of life.

ATANC: acid-treated activated nanocarbon

BG: bioglass

BSA: bovine serum albumin

CA: catechol

CNF: cellulose nanofibrils

DBD: dielectric barrier discharge

DLC: diamond-like carbon

EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate

FANC: functionalized activated nanocarbon

FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

GO: graphene oxide

GRA-PCA: grey relational analysis coupled with principal component analysis

HDPE: high-density polyethylene

mGO: modified graphene oxide

MMT: montmorillonite

MW: molecular weight

MWCNTs: multi-walled carbon nanotubes

n-Hap: nano-hydroxyapatite

ODPA: octadecylphosphonic acid

PE-g-MAH: polyethylene-grafted maleic anhydride

PEI: polyethyleneimine

PO: polyolefin

pSBMA: poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate)

PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene

rGO: reduced graphene oxide

SBF: simulated body fluid

SEM: scanning electron microscopy

SPIF: Single-Point Incremental Forming process

ta-C: tetrahedral amorphous carbon

TEM: transmission electron microscopy

Tob: tobramycin

UHMWPE: ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene

VE: Vitamin E

XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

α-T: α-tocopherol

LL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. FK: Conceptualization. BG: Investigation. ZY: Investigation. DW: Validation. DZ: Writing—original draft. HS: Conceptualization. WY: Writing—review & editing. YD: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The financial supports were funded by Basic Research Program of Jiangsu [BK20250294], the 2025 Jiangsu Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents, and the SINOPEC major scientific and technological projects [223334]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1047

Download: 18

Times Cited: 0