Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3922-025X

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 125-8585, Japan

2Research Institute for Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science, Chiba 278-8510, Japan

Email: s.510@rs.tus.ac.jp

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8088-9070

Explor BioMat-X. 2026;3:101357 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2026.101357

Received: November 10, 2025 Accepted: January 22, 2026 Published: February 03, 2026

Academic Editor: Fahmi Zaïri, University of Lille, France

Aim: Although polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is more hydrophobic than polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) in fluorocarbon polymer (FCP) membrane filters, it has been reported that the rate of amyloid fibril formation is faster on PVDF than on PTFE. To clarify whether the effect is due to the membrane’s chemical structure or its hydrophobicity at the membrane interface, studies on amyloid fibril formation were conducted using both hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF and PTFE membranes.

Methods: Heat-treated insulin (INS) was adsorbed onto the FCP membrane filters. Gaussian integrals were employed to determine the amounts of β-sheet and their abundance ratios by curve fitting of attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectra.

Results: Adsorbed heat-treated INS onto the FCP membrane filters showed a β-sheet form, with a similar or higher affinity in comparison with that of the β-rich concanavalin A. The adsorption followed a sigmoidal curve with a 2-hour lag time, reaching a plateau after 4–5 hours. The spectral patterns of the adsorbed INS indicated the β-sheet form, demonstrating that INS transformed into β-sheet and then, or simultaneously, adsorbed onto the FCP membrane filters.

Conclusions: The results regarding the rate and strength of amyloid fibril formation for each FCP membrane filter suggest that, beyond the membrane’s surface hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, other factors, such as the electron affinity of hydrogen in the PVDF membrane, also influence nucleation. This study provides insight into the role of INS in amyloid fibril formation within FCP membrane filters.

Fluorocarbon polymers (FCPs) offer numerous advantages, including thermal stability, excellent chemical resistance, and high mechanical strength, making them suitable for a wide range of applications [1–5]. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) porous membranes are ideal for filters because of their strong C–F bonds, minimal interactions, and inability to adsorb due to hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions [6].

The authors discovered that several 9-phenyl xanthene-based dyes can adsorb onto PTFE membrane filters with completely inactive interfaces [7]. This indicates that these flat molecules might self-organize into a lattice along the interface, resembling a two-dimensional crystal [8]. An acidic xanthene derivative, fluorescein, stained the FCP membrane filters because this fluorescent dye likely forms a self-organized association on the FCP membrane interface through intermolecular π–π stacking of its xanthene scaffolds [8]. Differently, an esterified and basic xanthene dye, rhodamine 6G, stained on PVDF rather than on PTFE membrane filters [8]. The PVDF polymer scaffold consists of –(CF2–CH2)– units containing an active methylene group. Therefore, basic rhodamine 6G may prefer binding to PVDF membranes rather than to PTFE. These experimental results could be related to the hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties of the FCP membrane filters or to the molecular specificity of the adsorbing ligands (chemical structure or electric charge).

Amyloid fibrils are believed to cause more than 50 diseases, including systemic amyloidosis, dialysis-associated amyloidosis, familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and type II diabetes. Developing therapies for these conditions requires understanding the mechanism of amyloid fibril formation. To investigate such a mechanism, researchers employ various approaches. The formation of amyloid fibrils (via protein misfolding) heavily depends on the environment surrounding the protein. Proteins in solution interact with and adhere to biological interfaces such as cell membranes, corneas, bones, articular menisci, arterial and venous walls, ventricles, and other structures.

It was reported that an FCP interface (Teflon®) promotes the formation of insulin (INS) aggregates [9]. This could suggest a mechanism for the self-organization or polymerization of denatured proteins at the fluorinated interface. A process called “nucleation-induced structural change” has been proposed as a mechanism for amyloid fibril formation [10–13]. This process involves the formation of primitive aggregates, known as oligomers, which serve as nuclei [14]. These nuclei reorganize the protein structure, resulting in elongated, self-assembled protein aggregates with a cross-β fibrous structure.

The current authors propose that amyloid fibrils, which form through the organization of β-sheets [15], resemble the two-dimensional crystals of adsorbed dye molecules described earlier [7, 8]. This idea is supported by the fact that phenylalanine’s aromatic rings, found in proteins such as calcitonin, are aligned on the same side of the β-sheet [16], and that interactions between these aromatic rings help stabilize the β-sheet structure [17]. Intermolecular π–π stacking (or hydrophobic interactions) between aromatic residues would promote adsorption onto the FCP membrane, similar to the self-organized dyes discussed above [7, 8] (and Congo red [15]). Based on these similarities, an FCP membrane capable of adsorbing amyloid fibers can be developed by adjusting the molecular structure and properties of the membrane filters.

Protein amyloid formation at FCP interfaces is essential [18, 19]. The interfacial environment promoted by PTFE and PVDF, which is different from the bulk aqueous phase, encourages amyloid fibrillation [20–22]. This suggests that proteins may transform into amyloid fibrils on PTFE and PVDF used as biomaterials in vivo. Importantly, PTFE and PVDF are classified as perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which were recently categorized as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2B) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [23]. It has been reported that protein-based adsorbents could be used to recover PFAS, which are difficult to remove [24]. This further underscores that protein adsorption onto FCPs, such as PTFE and PVDF, is unavoidable.

The fibrillation rate of INS on synthetic polymer interfaces, including regenerated cellulose, polyether sulfone, polyethylene, PVDF, and PTFE, has been studied, confirming that nucleation occurs faster at the membrane interface than in solution, especially for FCP membranes [22]. Although PTFE is more hydrophobic than PVDF [25], the formation rate of amyloid fibrils is faster on PVDF membrane filters. Whether the adsorption rate relates to molecular structure or interfacial hydrophobicity remains uncertain, with significant implications. The effectiveness of the membranous structure and interfacial hydrophobicity is intriguing in the context of amyloid fibril formation.

Frequently used INS is regarded as an ideal model protein for forming amyloid fibrils both in solution and on membrane interfaces [22, 26, 27]. Techniques for studying amyloid fibrils in vitro include Congo red staining [28], thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence [29], circular dichroism [30], Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) [31], nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [32], X-ray diffraction [33], small-angle X-ray scattering [34], atomic force microscopy [35], dynamic light scattering [36], and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy [37]. There are only a few methods for measuring solids, such as membrane-bound amyloid fibrils. It is expected that reagents like Congo red and ThT can affect membranes and are challenging to handle. It was predicted that attenuated total reflection (ATR)-FTIR would be the most effective method, as it allows quantitative assessment of secondary structures and rapid analysis of membranous interfaces [38–41].

In the present study, the adsorption of human recombinant INS onto hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF and PTFE membrane filters, as well as changes in secondary structure, were analyzed using ATR-FTIR, confirming the formation of amyloid fibrils. This suggested that different mechanisms of amyloid fibril formation exist even among similar FCPs. Since protein amyloid fibrillation is an irreversible, long-term process in vivo, further understanding of the fibrillation mechanism could be enhanced by using more suitable biological models that incorporate complex membranous structures and their interfacial properties.

Human recombinant INS, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and ThT were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. (St. Louis, MO, USA) provided concanavalin A (ConA) lyophilized powder containing approximately 15% protein, primarily balanced with NaCl. The Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit was purchased from TaKaRa Bio Inc. (Shiga, Japan). FCP membrane filters—hydrophobic PTFE with φ 0.22 μm pore (FGLP04700), hydrophilic PTFE with φ 0.45 μm pore (JHWP04700), hydrophobic PVDF with φ 0.22 μm pore (GVHP04700), and hydrophilic PVDF with φ 0.22 μm pore (GVWP04700)—were supplied by Merck & Co. Inc. (Darmstadt, Germany).

Before starting the experiments, all protein solutions were prepared in 25 mM HCl and 100 mM NaCl, then adjusted to pH 1.6. A ribbon-shaped FCP membrane filter with an area of 867 cm2 was added to the protein solution (0–2 mg/mL) at 338 K, and the mixture was shaken at 120 rpm for 24 hours. The protein content in the sample was measured using colorimetry, based on the chromophoric chelation of protein with the BCA-Cu(I) complex, known as the BCA assay. The protein concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 562 nm after mixing 25 μL of the sample solution (with the FCP membrane removed) with 200 μL of reagent solution.

Meanwhile, the protein adsorption onto the FCP membrane was performed as follows: The FCP membrane was cut into a 2 cm by 2 cm square. It was incubated in a buffer solution (pH 1.6) containing the sample protein at 2 mg/mL for 0 to 12 hours at 338 K (65°C). Afterwards, the FCP membrane was placed between bundled dustless cleaning papers (Kimwipes®, Nippon Paper Crecia Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and dried for 24 hours at room temperature. The thickness of the coated membrane was measured at ten different locations on the membrane fragment using a dial thickness gauge from Teclock Corp. (Nagano, Japan).

Membrane fragments before and after protein adsorption were mounted on a sample stage using double-sided insulating adhesive tape and coated with platinum in an ion sputter coater (JFC-1600, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Ultrafine photograms were captured with a scanning electron microscope (SEM), JSM-6060LA, JEOL Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded using an FTIR spectrometer (Frontier, PerkinElmer Co., Massachusetts, US) equipped with a universal attenuated total reflectance accessory. A force of 100 N was applied to more than three samples at 298 K, and the spectra were scanned from 1,700 cm−1 to 1,600 cm−1 at 1 cm−1 intervals, with 128 integration cycles. Nonlinear curve fitting of the average spectra was performed using a linear combination of Gaussian bell-shaped functions via the Solver module in Microsoft Excel 2016, employing the generalized reduced gradient (GRG) nonlinear option.

where ν and S represent wavenumber and background, respectively, the individual parameters for amplitude (Ai), peak position of wavenumber (μi), and standard deviation (σi) were minimized across trials using the tentative parameters. The sum of squared deviations (SS) between observed and predicted values was considered acceptable if it accounted for less than 0.1% of the variance on the logarithmic scale.

INS amyloid formation involves conversion of α-helices into β-strands, dimerization through cross-β-sheet formation, and fibrillation resulting from the stacking of dimeric units [15]. In this study, BSA, which has a high percentage of α-helix regions (84%) as an α-helix-rich model, and ConA, which is abundant in regular β-sheets (42%) as a β-sheet-rich model [42], were used as controls to examine amyloid trapped on FCP membrane filters. Human recombinant INS was heat-treated at 338 K for 6 hours and verified by ThT fluorescence staining (Figure S1).

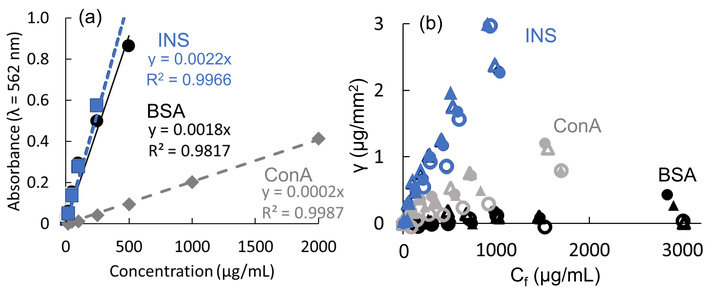

The BCA assay quantified protein levels of heat-treated INS, ConA, and BSA, both with and without FCP membranes (Figure 1). The reductions observed with FCP membranes corresponded to the adsorbed amounts, γ. Although BSA is commonly used as a protein calibration standard, heat-treated INS yields a similar slope, the extinction coefficient of ConA was significantly lower—about one-tenth—that of the standard (Figure 1a). The adsorption amounts of INS and ConA on all FCP membranes increased proportionally with the free concentration (Figure 1b). The quantity of INS adsorbed on the FCP membranes was more than twice that of ConA, while BSA showed minimal adsorption. The FCP membranes appear to favor β-sheet-enriched structures over α-helix-enriched structures, as BSA is rich in α-helices while the other two are abundant in β-structures.

BCA Assay Quantities of Proteins. (a) Calibrations for BCA assay absorbances of heat-treated INS (blue), BSA (black), and ConA (gray), and (b) their adsorbed amounts γ on hydrophobic PTFE (closed triangles), hydrophilic PTFE (open triangles), hydrophobic PVDF (closed circles), and hydrophilic PVDF (open circles).

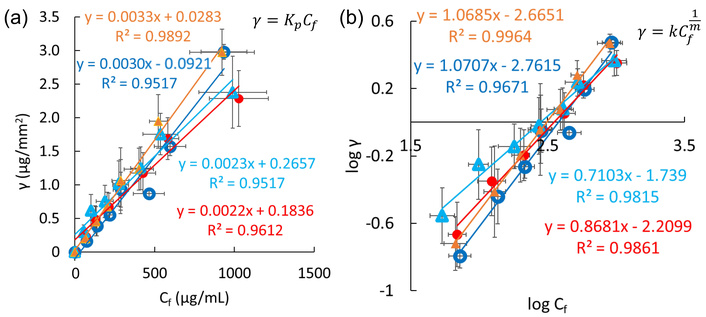

Figure 2 shows INS adsorption on FCP membranes, using Henry’s equation for the γ-Cf diagram and Freundlich’s equation for their log-log (log γ-log Cf) diagram. For BSA and ConA, these analyses are presented in Figure S2. Both methods measure the amount of adsorbed INS and ConA relative to their free concentrations, indicating that the membrane is not saturated within the 0–2 mg/mL concentration range. When the INS solution was not heat-treated at 338 K, no adsorption on the FCP membrane was observed. The slopes of log γ-log Cf curves based on Freundlich’s equation (Figure 2b) correspond to the exponent of Cf, with the reciprocal correlating with the adsorption index k (see the equation in Figure 2b). The indices for hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF were 1.15 and 0.934, respectively, while for hydrophobic and hydrophilic PTFE they were 0.936 and 1.41, respectively. Heat-treated INS adsorbed to all FCP membranes, with no significant differences.

Analyses of INS adsorption. Hydrophilic (blue open circles) and hydrophobic PVDF (red closed circles), as well as hydrophilic (light blue open triangles) and hydrophobic PTFE (amber closed triangles), based on Henry’s equation (a) and Freundlich’s equation (b). Error bars on the ordinate and abscissa represent standard deviations from three or more experiments.

The proteins adsorbed on FCP membranes were not α-helix-rich BSA but β-sheet-rich ConA and heat-treated INS. Since heat-denaturation is believed to increase the β-sheets in INS, it can be concluded that adsorption on FCP membranes requires the presence of β-sheet-rich regions. When comparing FCP membranes, the FCP type (PVDF or PTFE) and hydrophobicity (hydrophobic or hydrophilic) had little effect on the amount of adsorbed protein.

Studies on the interaction of purified proteins such as human serum albumin, human immunoglobulin G, and human fibrinogen with adsorbent interfaces, such as octyl sepharose and silanized glass particles, have demonstrated that the amount adsorbed follows a simple Henry-type isotherm. This amount increases proportionally with the bulk solution concentration until interfacial saturation is reached [43–45]. Assuming that the protein adsorbed on the FCP membranes was at the concentration before reaching interfacial saturation, our findings are consistent with the previous report. However, contrary to reports in which the slope of the Henry-type adsorption isotherm systematically decreases with increasing hydrophilicity of the adsorbate [45], the slope did not change much with the interface properties of the FCP membranes.

Subsequently, we analyzed linear plots based on Langmuir-type adsorption isotherm equations to verify the binding mechanisms. Figure S3 shows Klotz’s double reciprocal plot, Hanes-Woolf’s (Cf/γ)-Cf plot, and Scatchard’s (γ/Cf)-γ plot for heat-treated INS binding to the FCP membranes. Since Klotz’s plot extends to low adsorbent concentrations, it does not fully capture the saturation features of Langmuir’s hyperbolic model. All FCP membranes demonstrated good relationships in Klotz’s plots for INS adsorption. However, the Hanes-Woolf and Scatchard plots did not show consistent linearity across the four membranes. We concluded that the Langmuir model is not suitable for these adsorptions, which aligns with the results from Henry’s approximation and the Freundlich tests. ConA exhibited properties similar to those of INS (Figure S4), while BSA adsorption was considered inadequate for analysis because Klotz’s plots could not be interpreted (Figure S5).

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory explains monolayer saturation and subsequent multilayer adsorption of adsorbates on a filled interface, classified as Type II by the IUPAC system. This multilayer model could apply if the heat-treated INS can bind to the adsorbed INS. The Dubinin-Radushkevich (DR) adsorption isotherm model is an empirical model used to describe adsorption onto microporous solids, assuming the adsorbent follows a Gaussian distribution. The DR model does not require a saturating monolayer for multilayer adsorption, which is classified as Type III by IUPAC. Figure S6 shows BET and DR plots for heated INS on FCP membranes. The BET plots could not accurately illustrate heat-treated INS adsorption on the FCP membranes, whereas the DR plots provided a better fit. Type III adsorption seems to better explain these observations. Figure S7 shows these plots for BSA and ConA, but they yield poor fits. Based on this analysis, the heat-treated INS adsorbed onto the FCP membranes in a Type III manner. This indicates that direct binding is ineffective, and multilayer adsorption occurs instead. Therefore, we conclude that heat-denatured INS likely polymerizes into fibrils on the FCP membranes.

Comparing the adsorption of different proteins (heat-treated INS, native BSA, and ConA) on FCP membrane filters suggests that the β-sheet formed during heat treatment of INS affects its affinity to the FCP membrane interface. This section further reveals the secondary structure of adsorbed INS on the membranes via ATR-FTIR spectrometry. Correspondences of the wavenumbers for structures were summarized as follows [15, 42, 46]: (cf. Figure S8)

1,600–1,800 cm–1 for the C=O stretching vibration (amide-I band)

1,652–1,660 cm–1 for the α-helical conformation (amide I band)

1,547–1,570 cm–1 for the C–N stretching/N–H bending vibrations (amide-II band)

1,545 cm–1 for the α-helical conformation (amide II band)

1,630–1,638 cm–1 and 1,528 cm–1 for the parallel β-sheets

1,622/1,692 cm–1 and 1,522 cm–1 for the antiparallel β-sheets

1,638–1,655 cm–1 and 1,535–1,545 cm–1 for the unordered peptides

Figure S9 illustrates the ATR-FTIR spectral evolution of heat-treated INS adsorbed on FCP membranes. These spectra show a prominent peak at about 1,628 cm–1 (corresponding to β-sheet amide I) and a shoulder at 1,660 cm–1 (corresponding to α-helix amide I), both increasing over time. The amide I signal patterns match those of fibril INS growing in solution, as reported [47], suggesting that the adsorbed protein should be INS amyloid fibrils.

According to the adsorption method described by Nayak et al. for amyloid fibril formation [22], an increase in the β-sheet ratio in total protein correlates with amyloid fibril formation. Seo et al. [48] assigned the Gaussian peaks to specific structures: the α-helix at 1,648–1,660 cm–1 and parallel β-sheet at 1,610–1,640 cm–1. The area under each peak was calculated using the Gaussian integral

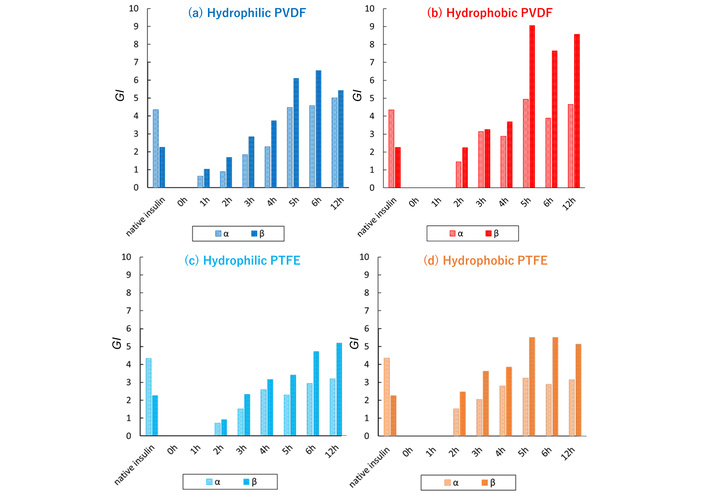

GI (Gaussian integral) values of α-helix and parallel β-sheet in INS adsorbed on different FCPs. Hydrophilic PVDF (a), hydrophobic PVDF (b), hydrophilic PTFE (c), and hydrophobic PTFE (d).

As shown in Figure 3, the heat-treated INS generally exhibited a higher proportion of β-sheet than native INS. The adsorption process lasted about 5–6 hours before equilibrium was reached. The GI values from hydrophobic membranes indicate slightly faster and greater β-sheet (amyloid) formation than those from hydrophilic membranes, with PVDF membranes showing the most pronounced effect (cf. Figure S11). These findings align with those of Nayak et al. [22], who suggest that hydrophobic interfaces nucleate amyloid formation more rapidly than hydrophilic ones. It is worth noting that the electronegativity of hydrogen in PVDF membranes and the hydrophobicity of the interface might also play a role. When examining the adsorption of small molecules onto hydrophobic and hydrophilic FCP membranes, rhodamine 6G self-organized solely on PTFE membranes [8]. Because its interaction with the polarized PVDF interface is probably more feasible than self-organization, the adsorption of the dye on the PVDF membrane would be canceled.

The ATR-FTIR spectra of α-rich BSA and β-rich ConA adsorbed on FCP membranes were similar across all samples, as shown in Figure S12. ConA is known to form amyloid fibrils when incubated at pH 8.9 and 310 K, with a characteristic peak around 1,620–1,600 cm–1 [49]. However, this peak was not observed, indicating that ConA was adsorbed without structural change. Therefore, it can be confirmed that BSA and ConA do not convert α-helix to β-sheet on the FCP membrane; only INS transforms from α-helix to β-sheet in solution and absorbs onto FCPs in a β-sheet-rich state.

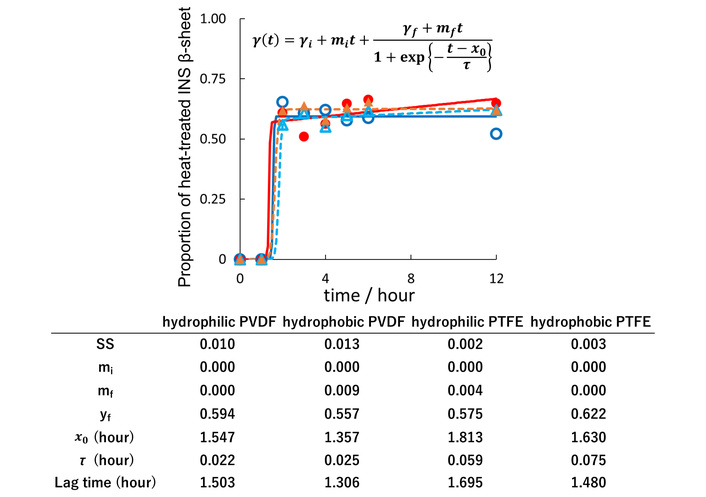

Figure 4 illustrates the change of the β-sheet proportion in heat-treated INS over 0–12 hours. Sakaguchi et al. [46] and Shiratori et al. [42] reported that heating globular proteins in a solution without a membrane causes aggregation, followed by a conformational change that forms β-sheets and leads to amyloid formation. However, results of this study showed that the proportion of β-sheet on the FCP membrane increased immediately—within 2 hours—and remained steady thereafter. This confirms that the protein, which aggregated in solution, experienced a conformational change and then, or simultaneously, bound to the membrane. Since α-rich BSA did not adsorb, but β-rich ConA did bind to the FCP membranes, heat-treated and denatured INS (amyloid fibrillated) can still adsorb to the FCP membranes.

The evolution of the proportion of β-sheet in heat-treated INS adsorbed on the FCP membrane. Hydrophilic (indigo) and hydrophobic PVDF (red), as well as hydrophilic (sky blue) and hydrophobic PTFE (amber). Curve fitting was done using a sigmoidal function [26]. Squared deviation (SS) represents the sum of squared deviations between observed and predicted values.

The previous results indicated that heat treatment of INS is needed to induce β-sheet formations. The Type III adsorption of heat-treated INS on the FCP membranes suggests a non-equilibrium distribution at the membrane interface. This section examined changes in membrane thickness and scanning electron microscopic images to verify whether INS amyloid fibrils are sparsely arranged, as in seaweeds.

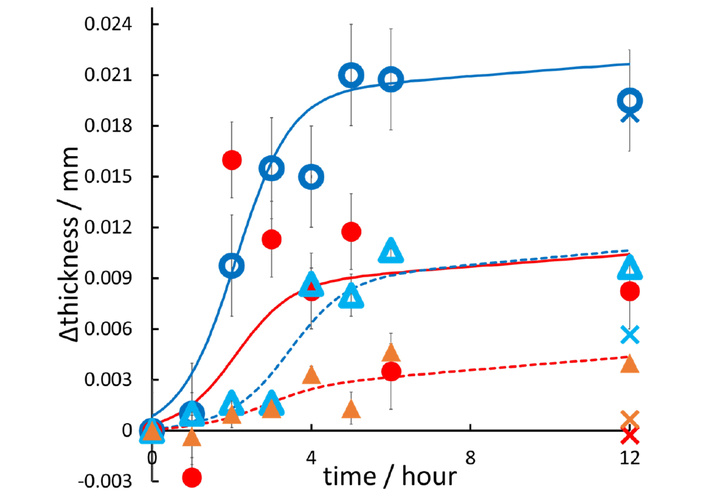

Figure 5 shows the change in thickness of the FCP membrane during the adsorption of heat-treated INS, which fits well with sigmoidal curves that increase steadily after a two-hour refractory period. These patterns are similar to the rise in β-sheet GI values shown in Figure 3. For the control FCPs without INS, the thicknesses of hydrophilic PVDF and hydrophilic PTFE membranes increased considerably after 12 hours, while both hydrophobic FCP membranes showed minimal change. Additionally, although Section “Adsorption isotherms of heat-treated proteins on the FCP membrane” indicated no remarkable difference in adsorption amount between hydrophobic and hydrophilic membranes, the difference in membrane thickness with and without INS adsorption after 12 hours was more noticeable for the hydrophobic membranes than for the hydrophilic membranes.

Thicknesses of the FCP membranes. Hydrophobic (red) and hydrophilic PVDF (indigo), as well as hydrophobic (amber) and hydrophilic PTFE (sky blue), which have adsorbed INS at incubation times ranging from 0 to 12 hours. Plots and error bars show the means ± standard deviations for measurements taken at ten locations. The X-marks at 12 hours on the abscissa, with colors matching the color codes above, indicate the control thickness of the FCP membranes. These results demonstrate that the hydrophobic PVDF (red) and PTFE (amber) did not undergo any thickness change over 12 hours in the absence of proteins, unlike their hydrophilic analogues.

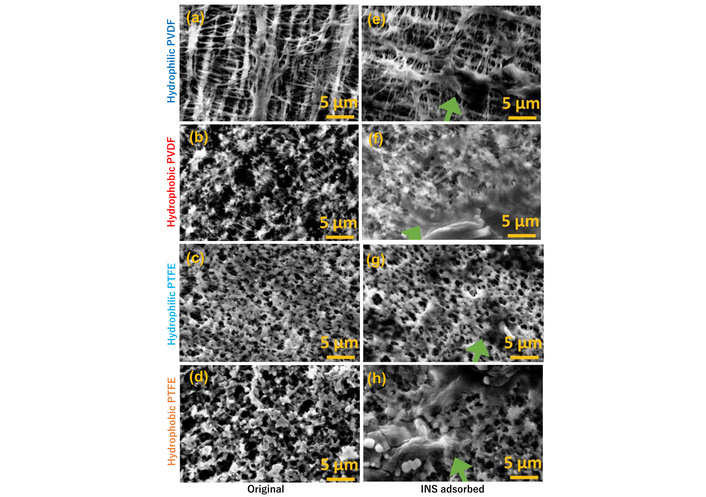

Figure 6 shows SEM images of FCP membranes before and after INS adsorption. After adsorption, the hydrophobic FCP membrane displayed large aggregates of INS amyloids, while the hydrophilic PVDF membrane remained almost unchanged. The hydrophilic PTFE membrane appeared to contain partially aggregated, paste-like materials along its fibers (indicated by moss-green arrows). These aggregates might come from tangled INS fibers in solution, forming seaweed-shaped, elongated amyloid that shrank on the FCP membrane filters during immobilization and vacuuming for SEM imaging. The presence of INS on FCP filters can be confirmed via characteristic ThT staining and FTIR spectroscopy, as mentioned earlier.

SEM images (15 kV, ×2,000) of FCP membranes before (a–d) and after (e–h) addition of 2 mg/mL INS and heat treatment for 12 hours.

The hydrophilic FCPs are hydrophobic on the inside, although they were surface-treated to increase the contact angle [50–52]. The hydrophilic PVDF membrane could swell and expand during incubation in INS solution (their thickness increased, see Figure 5), creating voids. INS enters the interior, causing conformational changes and amyloid fibril formation, which leads to the adsorption of amyloid fibrils along the hydrophobic membrane fibers. The thicknesses were almost the same with and without INS adsorbed (Figure 5). In contrast, the hydrophobic PVDF and hydrophobic PTFE membranes did not swell. INS amyloid fibrils adsorbed onto the hydrophobic environment on the membrane surface and extended upward vertically on the membrane, like seaweed (as indicated by the DR model adapted to IUPAC Type III absorption), likely affecting membrane thickness. We concluded that Type III multilayer adsorption of heat-treated INS occurred, with a similar quantitative behavior, albeit not identical, in both hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF/PTFE membranes.

The FCP interfaces examined in this study significantly impact INS’s conformational change and adsorption properties during amyloid formation. Those would specifically target the nucleation or formation of amyloid fibrils, thereby accelerating amyloid formation.

Henry’s, Freundlich’s, and DR plots significantly aid in estimating INS adsorption on both hydrophobic and hydrophilic PVDF/PTFE. The amount of INS adsorbed onto the FCP membrane does not reach saturation, showing no marked change despite differences in membrane properties. Additionally, the binding mode can be modeled by the DR adsorption isotherm, a Type III model, indicating that multilayer adsorption occurs without a saturated monolayer.

Based on the GI values from the ATR-FTIR spectra, the hydrophobic membrane generally showed a slightly faster and more amyloid formation than the hydrophilic membrane, especially for the PVDF membrane. These findings suggest that, beyond the surface’s hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties, other factors—such as the electron affinity of hydrogen in the PVDF membrane—may also affect nucleation. Additionally, the rapid increase in the proportion of β-sheets on the membrane indicates that amyloid fibrils with high β-sheet content formed in solution before adsorbing onto the FCP membrane.

Conformational changes and amyloid formation occur within the hydrophilic PVDF and PTFE membranes. The hydrophobic PVDF and hydrophobic PTFE membranes adsorb INS amyloid fibers formed in solution. Amyloid formation on hydrophilic PTFE is related to both internal and surface properties. Therefore, the way INS adsorbs onto the FCP membrane depends on the membrane’s surface properties, such as hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity.

This study provides further details on the INS amyloid fibril formation on FCP membranes. This may help clarify amyloid fibril formation at the interface and provide a new method for observing the effects of inhibitors on amyloid formation under different experimental conditions.

ATR: attenuated total reflection

BCA: bicinchoninic acid, i.e., 2-(4-carboxyquinolin-2-yl)quinoline-4-carboxylic acid (CAS NR 1245-13-2)

BET: Brunauer-Emmett-Teller

BSA: bovine serum albumin

ConA: concanavalin A

DR: Dubinin-Radushkevich

FCPs: fluorocarbon polymers

FTIR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

GI: Gaussian integral

INS: insulin

IUPAC: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

PFAS: perfluoroalkyl substances

PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene

PVDF: polyvinylidene fluoride

SEM: scanning electron microscope

SS: squared differences

ThT: thioflavin T, i.e., 2-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-3,6-dimethyl-1,3-benzothiazol-3-ium chloride (CAS NR 2390-54-7)

The supplementary figures for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/101357_sup_1.pdf.

The authors thank Professor Kazushi Komatsu of the Department of Mathematics at Kochi University for valuable discussions.

KM: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Visualization. ST: Writing—review & editing, Investigation. YK: Writing—review & editing. RK: Writing—review & editing. TH: Writing—review & editing. SG: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This research received no external funding.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 436

Download: 10

Times Cited: 0