Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Email: salhabardi@ksu.edu.sa

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8077-9103

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7736-6279

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Affiliation:

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia

Explor BioMat-X. 2025;2:101355 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2025.101355

Received: July 28, 2025 Accepted: December 10, 2025 Published: December 22, 2025

Academic Editor: Omid Akhavan, Sharif University of Technology, Iran

Aim: Osimertinib’s clinical application is limited by poor aqueous solubility and systemic toxicity. Nano-niosomal formulations can address these challenges by providing controlled release and enhancing delivery. To develop and systematically evaluate nano-niosomal formulations of osimertinib using different surfactants, focusing on physicochemical characteristics, release kinetics, and cytotoxic activity.

Methods: Four niosomal formulations were prepared using Span 60, Tween 60, Pluronic F-127, and Brij 52 (each at a 1:1 cholesterol-to-surfactant ratio). Particle size, zeta potential, and entrapment efficiency were measured. In vitro drug release was analyzed using Franz diffusion cells and fitted to standard kinetic models. Cytotoxicity was assessed by MTT assay in KAIMRC-2, MDA-MB231, and HCT-116 cell lines. Vesicle morphology was visualized by transmission electron microscopy.

Results: All nano-niosomal formulations showed nanoscale particle sizes (47–292 nm), negative zeta potentials (−18.7 to −26.5 mV), and high entrapment efficiencies (69.8%–76.2%). Release studies indicated Span 60, Tween 60, and Pluronic F-127 followed diffusion-controlled kinetics (Higuchi/Korsmeyer–Peppas model, R2 up to 0.97), while Brij 52 provided a sustained zero-order release (R2 = 0.98). Compared to free osimertinib, all niosomal systems significantly prolonged release. Cytotoxicity studies demonstrated that all formulations enhanced anti-cancer effects, with Span 60-based niosomes exhibiting the greatest potency across cell lines.

Conclusions: Optimized nano-niosomal encapsulation of osimertinib enables sustained and controlled drug release, improved cellular uptake, and enhanced cytotoxicity in vitro. Differences in surfactant composition critically influence formulation performance, supporting the further development of niosomal osimertinib as a promising strategy for oncological drug delivery applications.

Nano-niosomes have emerged as highly effective drug delivery platforms due to their ability to encapsulate poorly water-soluble (hydrophobic) therapeutics, enhance bioavailability, and provide controlled and sustained drug release, enabled by the tunable bilayer structure composed of non-ionic surfactants and cholesterol [1, 2]. The physicochemical properties of the surfactant—specifically its hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), alkyl chain length, and gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperature—critically influence key characteristics of the vesicles, including particle size, encapsulation efficiency, bilayer stability, and drug release behavior [3]. For example, non-ionic surfactants with lower HLB values, such as Span® series (e.g., Span 80, HLB 4.3) [4], are known to yield smaller niosomal vesicles (often < 100 nm) with superior drug entrapment efficiency compared to higher-HLB surfactants like polysorbates (Tween® family) [5].

Nano-niosomes have attracted significant attention as drug delivery vehicles due to their unique structural and compositional features. Compared to established lipid-based nanocarriers such as liposomes, niosomes offer several distinct advantages: They are generally more stable upon storage, less prone to oxidative degradation, and can be produced cost-effectively owing to the use of non-ionic surfactants instead of phospholipids, while still affording high drug-loading efficiency and structural versatility [6]. Unlike liposomes—which may rely on expensive or sensitive lipid components and are more susceptible to hydrolytic degradation—niosomes are less immunogenic, exhibit reduced batch-to-batch variability, and allow for facile surface modification, making them especially attractive for clinical translation in drug delivery applications [7].

Osimertinib, a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor currently employed in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), faces several clinical limitations, including low aqueous solubility, dose-limiting systemic toxicity, and highly variable pharmacokinetics [8]. Encapsulating osimertinib within nano-niosomes has the potential to overcome these challenges by increasing solubility, extending systemic circulation, and promoting more targeted delivery to tumor tissues [9]. Previous studies involving the niosomal delivery of hydrophobic antitumor agents such as docetaxel and luteolin have shown that the physicochemical attributes of the chosen surfactant can significantly dictate both drug release kinetics and cytotoxic efficacy, with Span 80-based niosomes, for example, achieved up to 74% entrapment of docetaxel, sustained drug release, and a 2.5–6.5-fold reduction in IC50 values relative to free drug in cancer cell models [10].

Recognizing the critical interplay between surfactant properties, vesicle architecture, dissolution kinetics, and anticancer performance, the present study aims to establish rational design criteria for optimizing EGFR inhibitor delivery and, thereby, potentially minimize off-target toxicity while maximizing therapeutic benefit in solid tumor malignancies [11]. Specifically, the primary objectives of this research were to formulate osimertinib-loaded nano-niosomal systems employing a range of surfactant types and to comprehensively characterize the resultant formulations in terms of their physicochemical attributes, colloidal stability, and structural morphology. Furthermore, the study sought to elucidate the in vitro drug release profiles of the different niosomal formulations using Franz-cell diffusion methodology, with quantitative release data modeled via the DD Solver computational program. Finally, the cytotoxic potential of these osimertinib-loaded nano-niosomes was systematically evaluated in vitro across multiple cancer cell lines, providing in-depth insight into their efficacy and safety profiles and informing the future development of advanced nanoscale EGFR inhibitor delivery systems.

Osimertinib powder (Cat. No. O7781; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used. Span 60 (Cat. No. 16611-71), Tween 60 (Cat. No. 16220-24), Pluronic F-127 (Cat. No. 16746-62), Brij 52 [polyoxyethylene (2) cetyl ether; C16E2] (Cat. No. 16736-61), and cholesterol (Cat. No. 034-03883) were all obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Ultrapure water was prepared with a Millipore purification system (Model Elix SA 67120; Millipore, Molsheim, France). All solvents employed in the study were of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade.

The drug (osimertinib), cholesterol, and surfactants (Span 60, Tween 60, Pluronic F-127, and Brij 52 [polyoxyethylene (2) cetyl ether; C16E2]) were each accurately weighed—osimertinib at 10 mg, cholesterol and surfactant at a fixed 1:1 weight ratio—then dissolved in 10 mL of absolute ethanol for each formulation (Table 1). The total drug concentration in the organic phase was thus 1 mg/mL. This ethanolic mixture was gradually injected into a preheated aqueous phase (60°C; containing polyvinyl alcohol), ensuring complete mixing. After stirring for 1 hour with a magnetic stirrer, the resultant dispersion was sonicated for 2 minutes before refrigeration. All formulation compositions are explicitly reported as mg of each component per batch and final concentrations as mg/mL in the dispersion medium.

Composition of osimertinib niosomal formulations.

| Formulation | Drug (mg) | Final concentration (mg/mL) | Cholesterol: surfactant ratio | Surfactant type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 10 mg | 1 mg/mL | 1:1 | Span 60 |

| F2 | 10 mg | 1 mg/mL | 1:1 | Tween 60 |

| F3 | 10 mg | 1 mg/mL | 1:1 | Pluronic F-127 |

| F4 | 10 mg | 1 mg/mL | 1:1 | Brij 52 (C16E2) |

The formed niosomes were characterized as follows. The spectrophotometric method for assay was performed by preparing standard stock solutions of osimertinib at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, prepared by dissolving 3 mg of the drug in 50 mL of 100 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; stock 1). From this stock, various aliquots were withdrawn and transferred to a series of 10 mL volumetric flasks, and the volumes were adjusted with the same medium to obtain six different concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 25 μg/mL (pH 7.4). The absorbance of osimertinib was measured at 206 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Model UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) to construct the calibration curve.

The vesicle size and polydispersity index of the prepared niosomes were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Nano sizer (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK), after suitable dilution with deionized water. The drug entrapment efficiency was determined indirectly by separating the non-entrapped drug via ultracentrifugation at 17,000 rpm for 45 minutes. The concentration of free drug in the supernatant was quantified using the previously established calibration curve, and the entrapment efficiency was then calculated accordingly.

The in vitro release profiles of osimertinib from niosomal formulations were assessed using Franz diffusion cells, with each formulation (1 mL dispersion) placed in dialysis bags of regenerated cellulose (molecular weight cutoff 8,000–12,000 Da) and incubated in 50 mL of release medium at 37°C. To ensure sink conditions for the poorly water-soluble osimertinib, the receptor medium was selected as PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.5% Tween 80, which increases drug solubility and mimics physiological conditions. At predetermined intervals (1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 50 hours), aliquots were withdrawn from the dialysate, and released drug was quantified spectrophotometrically. Sink conditions were confirmed by measuring osimertinib solubility in the release medium prior to experimentation, ensuring the medium volume and composition exceeded three times the highest drug concentration encountered during the study.

The kinetics of drug release from the niosomes were analyzed using the DD Solver add-in for Microsoft Excel. The drug release data were fitted to several mathematical models, including zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, and Hixson–Crowell models. For each model, the correlation coefficient (R2) was calculated to evaluate the goodness of fit, and the model with the highest R2 value was considered the most suitable for describing the drug release kinetics.

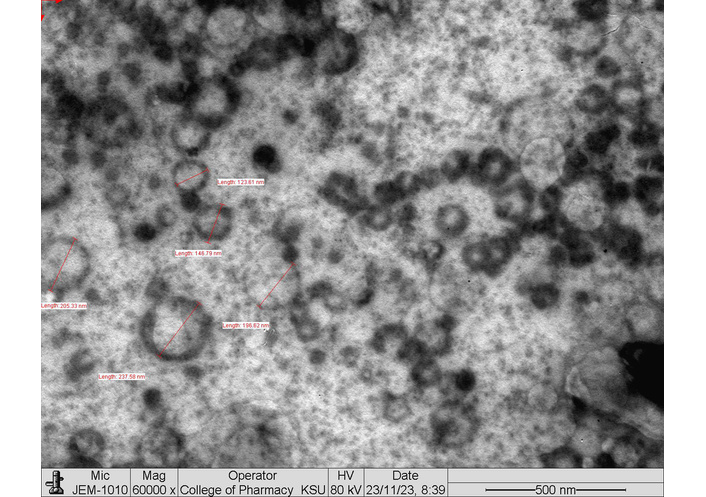

The morphology of prepared niosomal vesicles was characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope. A drop of the niosome sample was placed onto a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to adsorb. Excess liquid was removed, and the grid was negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0) for 30–60 seconds, then air-dried at room temperature. The grids were examined using the JEOL JEM-1400 TEM at 80–120 kV, and images were captured at various magnifications to assess the size, shape, and surface characteristics of the vesicles.

The cytotoxicity of the niosomal formulations was evaluated using three distinct and commercialized cancer cell lines: KAIMRC‑2 breast cancer cells were obtained from King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). MDA‑MB231 (ATCC HTB‑26) and HCT‑116 (ATCC CCL‑247) human cancer cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). All cell lines were cultured according to recommended protocols in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA), maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. According to the supplier’s quality documentation, all cell lines had been authenticated by STR profiling, and the profiles matched the reference STR patterns for KAIMRC‑2, MDA‑MB231, and HCT‑116, with no evidence of cross‑contamination. The cytotoxicity of the niosomal formulations was evaluated to provide comprehensive insights into the potential effects of osimertinib-loaded niosomes across various cell types relevant to scarring, cancer progression, and tissue remodeling. For each cell line, the experimental design included blank niosomes (without drug) to determine the potential cytotoxicity caused by the surfactant/vehicle, and a solvent control (DMSO) to rule out any effects attributable to the solvent alone. Cell viability assays were conducted after exposure to increasing concentrations of the niosomal formulations (F1–F4), blank niosomes, and solvent controls, with results normalized against untreated control cells. The measured cytotoxicity attributable to blank niosomes or DMSO was subtracted from the corresponding results for drug-containing formulations to quantify the specific contribution of osimertinib to overall cytotoxicity. The standard cytotoxicity assay used in this study was the MTT assay. After incubation with niosomal formulations, blank niosomes, or controls, cells were exposed to 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution for 3–4 hours at 37°C. Formazan crystals formed by viable cells were dissolved in DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to assess differences among multiple groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

The results in Table 2 show how the choice of surfactant markedly influences the characteristics of osimertinib-loaded niosomal formulations. Among the four formulations, F3 containing Pluronic F-127 exhibited the smallest particle size (47 nm), a highly negative zeta potential (–26.5 mV), and a moderate entrapment efficiency (69.8%). This indicates that Pluronic F-127 produces very small, stable vesicles, likely due to its block copolymer structure promoting compact assembly.

Characterization of osimertinib niosomal formulations: influence of surfactant type on particle size, zeta potential, and entrapment efficiency.

| Formulation | Surfactant type | Particle size (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | Entrapment efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Span 60 | 112 ± 7 | −23.2 ± 1.5 | 71.5 ± 2.1 |

| F2 | Tween 60 | 292 ± 13 | −18.7 ± 1.1 | 76.2 ± 1.7 |

| F3 | Pluronic F-127 | 47 ± 5 | −26.5 ± 1.8 | 69.8 ± 2.4 |

| F4 | Brij 52 (C16E2) | 126 ± 9 | −21.4 ± 1.3 | 74.0 ± 1.9 |

Values presented as mean ± SD, n = 3.

F1 with Span 60 yielded vesicles of 112 nm, a zeta potential of –23.2 mV, and an entrapment efficiency of 71.5%. Span 60 is known for forming relatively stable niosomes with good drug loading due to its long saturated alkyl chain and low HLB, explaining its favorable performance. This high entrapment efficiency is consistent with literature, which frequently reports superior drug loading for Span 60-based niosomes due to their higher phase‑transition temperature and longer saturated alkyl chain, leading to reduced membrane leakage and improved vesicle stability [12]. F2 (Tween 60) formed larger niosomes (292 nm) with a zeta potential of –18.7 mV and the highest entrapment efficiency (76.2%). Tween 60, having a higher HLB than Span 60, typically produces larger vesicles and can enhance drug encapsulation due to increased hydration and flexibility of the bilayer. This also aligns with findings that Tween-based niosomes may provide higher drug loading, but often at the expense of larger and possibly less stable particles [13].

F4, using Brij 52 (C16E2), resulted in intermediate vesicle size (126 nm), a zeta potential of –21.4 mV, and an entrapment efficiency of 74.0%. Brij surfactants are recognized for forming uniform niosomes with good stability and drug loading, with results here comparable to Span 60 and Tween 60 formulations.

The negative zeta potentials across all formulations suggest colloidal stability (typically, values greater than ±20 mV help prevent aggregation), while the high drug entrapment efficiencies and controlled sizes in the nanometer range are desirable for drug delivery applications.

Overall, these results reflect established surfactant properties in niosome formation: Saturated surfactants like Span 60 and block copolymers like Pluronic F-127 foster smaller, stable vesicles, while higher HLB surfactants such as Tween 60 may increase entrapment but also vesicle size. Brij 52 offers a balance between vesicle size and entrapment efficiency, supporting its use as an alternative to Span or Tween.

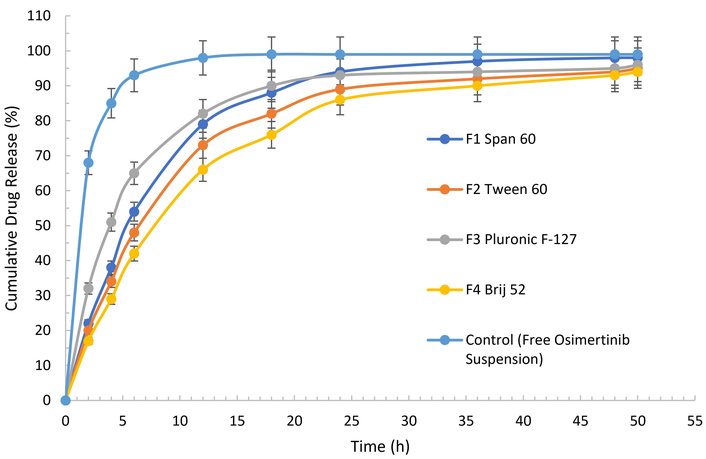

The in vitro release profiles of osimertinib from various niosomal formulations and a free drug suspension (control) were systematically compared (Figure 1). All niosomal formulations—F1 (Span 60), F2 (Tween 60), F3 (Pluronic F-127), and F4 (Brij 52)—demonstrated a sustained drug release pattern over 50 hours. In contrast, the control group containing free osimertinib suspension exhibited a rapid burst release, with approximately 68% of the drug released within the first 2 hours and over 85% released by 4 hours. Complete drug release from the free suspension was nearly achieved by 12 hours, exceeding 98%, and remained constant thereafter.

In vitro cumulative release profiles of osimertinib from niosomal formulations and free drug suspension.

Among the niosomal systems, the formulation containing Pluronic F-127 (F3) showed the fastest initial release, with 32% of osimertinib released after 2 hours and 65% by 6 hours, eventually reaching 96% at 50 hours. Span 60-based niosomes (F1) also exhibited accelerated but controlled release, with cumulative release steadily increasing to 98% at 50 hours. Tween 60 (F2) and Brij 52 (F4) formulations displayed more gradual drug release profiles, achieving 95% and 94% cumulative release, respectively, at 50 hours.

These findings confirmed that encapsulation of osimertinib in niosomal carriers significantly prolonged drug release compared to the free suspension. The sustained release observed for all niosomal formulations suggests their advantageous potential for controlled delivery, with the specific release rate influenced by surfactant composition. Notably, while free osimertinib was released rapidly, the niosomal systems enabled prolonged and regulated drug delivery over extended periods, supporting their utility for therapeutic applications requiring sustained drug levels.

The release kinetics of osimertinib from the four niosomal formulations were evaluated by fitting the in vitro release data to five mathematical models: zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, and Hixson–Crowell (Table 3). For F1 (Span 60), the highest correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.97) was observed with the Higuchi model, indicating that drug release was predominantly governed by diffusion from the niosomal matrix. Similar trends were seen for F2 (Tween 60) and F3 (Pluronic F-127), where the Higuchi (R2 = 0.95 and 0.97, respectively) and Korsmeyer–Peppas (R2 = 0.94 and 0.96, respectively) models also provided the best fit, further supporting a diffusion-controlled release mechanism for these formulations. In contrast, F4 (Brij 52) demonstrated its greatest correlation with the zero-order model (R2 = 0.98), suggesting a more constant and sustained release rate over time. Lower correlation coefficients were consistently observed for the first-order and Hixson–Crowell models across all formulations. Collectively, these results demonstrate that while Span 60, Tween 60, and Pluronic F-127 niosomes released osimertinib primarily via diffusion mechanisms, Brij 52-based niosomes exhibited kinetics consistent with a zero-order, constant release profile.

Correlation coefficients (R2) for mathematical models fitted to osimertinib release from niosomal formulations.

| Model | F1 (Span 60) R2 | F2 (Tween 60) R2 | F3 (Pluronic F-127) R2 | F4 (Brij 52) R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.98 |

| First-order | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| Higuchi | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| Hixson–Crowell | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.87 |

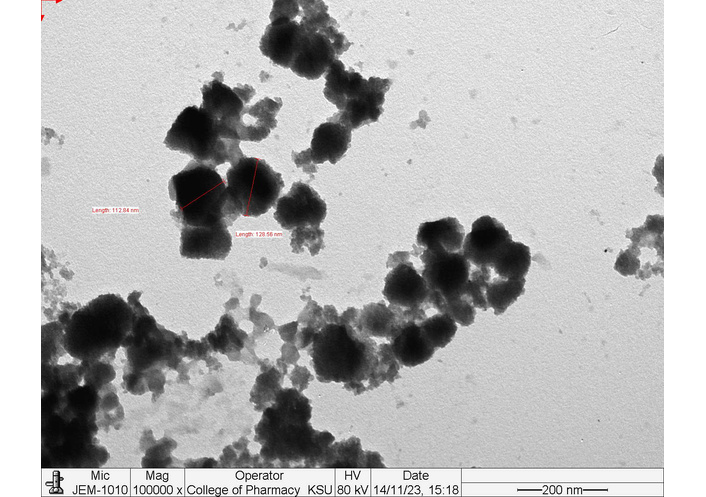

The TEM analysis of the F1 (Span 60) niosomal formulation revealed that the vesicles were well-defined, spherical to quasi-spherical in shape, with measured sizes around 113–129 nm, in agreement with DLS results for this formulation (Figure 2). The vesicles displayed distinct bilayer structures highlighted by negative staining with phosphotungstic acid, and while some aggregates were present, most particles remained discrete, reflecting good colloidal stability consistent with the measured zeta potential.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of F1 (Span 60) niosomal vesicles demonstrating spherical morphology and nanoscale particle size.

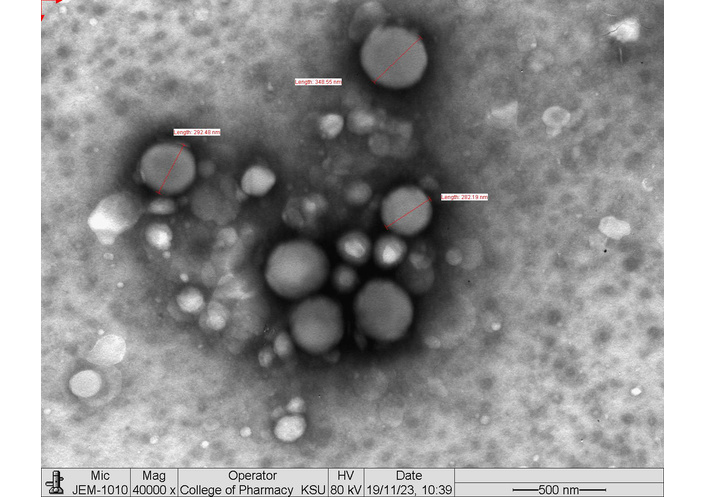

The TEM analysis of the F2 (Tween 60) niosomal formulation showed mostly spherical or quasi-spherical vesicles with uniform, well-defined boundaries and sizes matching nanoscale dimensions (around 292 nm), as indicated by particle measurements (Figure 3). The vesicles displayed clear negative staining and, while some moderate aggregation was noted, most particles appeared discrete, reflecting reasonable colloidal stability supported by the measured zeta potential. The comparatively larger size of these Tween 60-based niosomes is attributed to the surfactant’s higher HLB, leading to greater bilayer hydration during formation.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of F2 (Tween 60) niosomal vesicles demonstrating spherical morphology and nanoscale particle size.

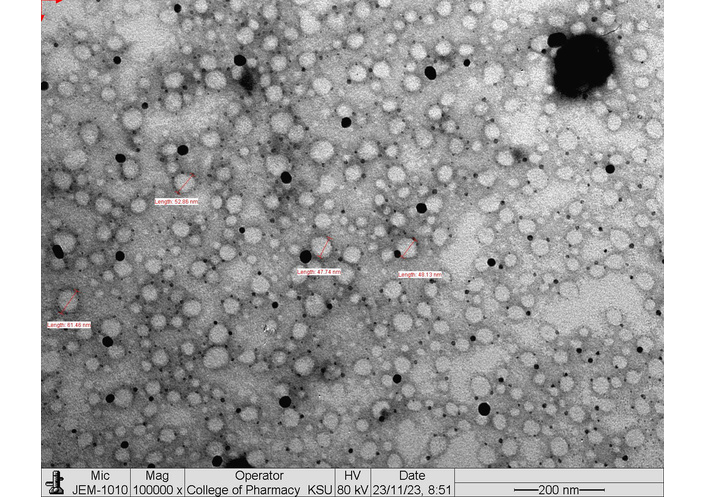

The TEM analysis of the F3 (Pluronic F-127) niosomal formulation revealed predominantly small, spherical vesicles with clearly defined, uniform boundaries and a narrow size distribution, consistent with its measured particle diameter of approximately 47 nm (Figure 4). The negative staining highlighted intact bilayer structures, and the small vesicle size observed aligns with the DLS data reported for this formulation. Minimal aggregation was present, reflecting high colloidal stability, further supported by the strongly negative zeta potential (–26.5 mV).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of F3 (Pluronic F-127) niosomal vesicles demonstrating spherical morphology and nanoscale particle size.

The TEM analysis of the F4 (Brij 52) niosomal formulation shows well-defined, predominantly spherical vesicles with distinct, uniform boundaries and sizes close to the nanoscale range (approximately 126 nm) (Figure 5). Negative staining with phosphotungstic acid highlights clear bilayer structures, and while minor aggregation is evident, most vesicles appear as separate, discrete particles.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of F4 (Brij 52) niosomal vesicles demonstrating spherical morphology and nanoscale particle size.

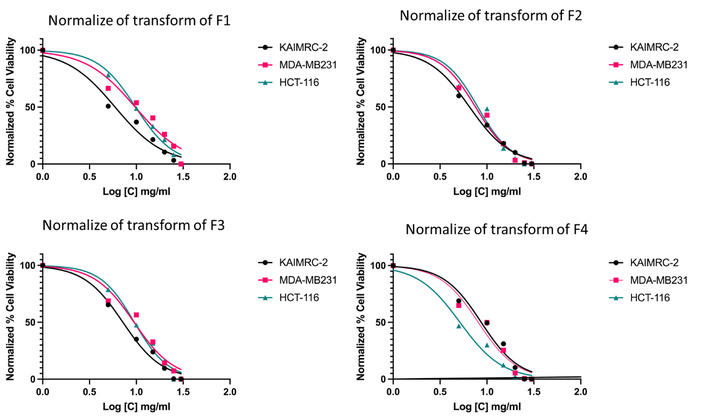

The comparative IC50 data clearly demonstrate that nano-niosomal encapsulation consistently enhances the in vitro cytotoxicity of osimertinib across all tested cell models. As summarized in Table 4, all formulations (F1–F4) produced lower IC50 values than the free drug in KAIMRC-2, MDA-MB231, and HCT-116 cells, confirming that niosomal delivery increases antiproliferative potency under identical experimental conditions. In KAIMRC-2 cells, which represent a breast cancer line derived from a Saudi patient, F1 (Span 60) and F2 (Tween 60) reduced the IC50 by approximately 29% and 41%, respectively, indicating particularly strong sensitivity of this cell line to surfactant-dependent modulation of drug delivery.

Comparative IC50 values for free osimertinib and osimertinib-loaded nano-niosomal formulations (F1–F4) against KAIMRC-2, MDA-MB231, and HCT-116 cell lines.

| Cell line | Treatment | Log IC50 | IC50 (µg/mL) | R2 | % Reduction vs. free OSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAIMRC-2 | Free OSI | 1.00 | 10.0 | 0.97 | – |

| KAIMRC-2 | F1 (Span 60) | 0.85 | 7.1 | 0.97 | 29% ↓ |

| KAIMRC-2 | F2 (Tween 60) | 0.77 | 5.9 | 0.92 | 41% ↓ |

| KAIMRC-2 | F3 (Pluronic F-127) | 0.86 | 8.6 | 0.94 | 14% ↓ |

| KAIMRC-2 | F4 (Brij 52) | 0.81 | 6.5 | 0.92 | 35% ↓ |

| MDA-MB231 | Free OSI | 1.05 | 11.2 | 0.96 | – |

| MDA-MB231 | F1 (Span 60) | 0.97 | 9.4 | 0.95 | 16% ↓ |

| MDA-MB231 | F2 (Tween 60) | 0.95 | 9.7 | 0.94 | 13% ↓ |

| MDA-MB231 | F3 (Pluronic F-127) | 0.90 | 8.0 | 0.96 | 29% ↓ |

| MDA-MB231 | F4 (Brij 52) | 0.87 | 7.5 | 0.93 | 33% ↓ |

| HCT-116 | Free OSI | 1.02 | 10.5 | 0.97 | – |

| HCT-116 | F1 (Span 60) | 0.97 | 9.5 | 0.97 | 10% ↓ |

| HCT-116 | F2 (Tween 60) | 0.99 | 9.9 | 0.98 | 6% ↓ |

| HCT-116 | F3 (Pluronic F-127) | 0.71 | 5.1 | 0.95 | 51% ↓ |

| HCT-116 | F4 (Brij 52) | 0.89 | 7.9 | 0.96 | 25% ↓ |

In MDA-MB231 triple-negative breast cancer cells, the enhancements were more modest overall but remained evident, with F1–F4 achieving IC50 reductions in the range of about 13–33% compared with free osimertinib, suggesting that even in this more aggressive phenotype, niosomal formulations can meaningfully improve cytotoxic efficacy. By contrast, in HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cells, a marked formulation-specific effect was observed, with F3 (Pluronic F-127) showing the greatest enhancement and lowering the IC50 by roughly 51%, while the other formulations produced smaller yet still appreciable reductions (about 6–25%) relative to the free drug. Across all conditions, the nonlinear regression fits yielded R2 values between 0.92 and 0.98, supporting the robustness and reproducibility of the dose–response curves and reinforcing the conclusion that nano-niosomes, particularly those based on Span 60, Tween 60, and Pluronic F-127, can significantly augment the cytotoxic performance of osimertinib in vitro.

The cytotoxicity of the four osimertinib niosomal formulations—F1 (Span 60), F2 (Tween 60), F3 (Pluronic F-127), and F4 (Brij 52)—was evaluated in vitro against KAIMRC-2 (black circles), MDA-MB231 (magenta squares), and HCT-116 (cyan triangles) cell lines using a cell viability assay (Figure 6). All formulations demonstrated a clear, concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability across all tested cell lines. F1 (Span 60) exhibited the most pronounced cytotoxic effect, resulting in a lower percentage of viable cells at lower concentrations relative to the other formulations. F2 (Tween 60) and F4 (Brij 52) produced similar cytotoxicity profiles, generally with slightly higher cell viabilities at equivalent concentrations. The F3 (Pluronic F-127) formulation showed a moderate cytotoxic response overall. At 1.5 mg/mL, the viability of HCT-116 cells was comparable to that of the other cell lines, without clear evidence of increased resistance. Overall, the results confirm that surfactant type influences cytotoxic potency, with Span 60-based niosomes providing the most efficient cell viability reduction. No major differences in sensitivity were observed among the three cancer cell lines, though minor variations at specific concentrations may occur. These findings collectively support that osimertinib niosomes, especially those incorporating Span 60, can achieve effective and enhanced cytotoxic activity in vitro across multiple tumor cell models.

In vitro cytotoxicity of osimertinib niosomal formulations with different surfactants against KAIMRC-2, MDA-MB231, and HCT-116 cell lines.

The findings from the present study highlight the pivotal role of surfactant selection in shaping the physicochemical properties, release characteristics, and biological performance of osimertinib-loaded nano-niosomal formulations. Systematic comparison of Span 60, Tween 60, Pluronic F-127, and Brij 52-based niosomes revealed marked differences in vesicle size, stability, drug entrapment efficiency, and, ultimately, therapeutic potential [13]. Notably, Span 60 and Pluronic F-127 yielded the smallest and most uniform particles, which are generally favored for enhanced uptake and biodistribution [14]. The pronounced negative zeta potentials across all formulations suggest robust colloidal stability, reducing the likelihood of aggregation and supporting longer circulation times—a crucial consideration for systemic drug delivery [15].

Release kinetics further demonstrated that surfactant identity governs the mechanism of drug diffusion from niosomes: Higuchi and Korsmeyer–Peppas models best fit the release profiles of Span 60, Tween 60, and Pluronic F-127 niosomes, indicating diffusion-dominated drug liberation [16]. In contrast, Brij 52-based niosomes exhibited nearly ideal zero-order release, implying a more constant and sustained drug delivery profile. Such tunable kinetics provide opportunities for tailoring niosomal systems to meet specific clinical requirements, potentially improving patient compliance and therapeutic precision [2].

The observed variations in cytotoxicity among F1–F4 can be directly attributed to their distinct physicochemical attributes. For example, the superior cytotoxicity of F1 (Span 60) is likely a consequence of its smaller and highly uniform vesicle size combined with favorable entrapment efficiency and a pronounced negative zeta potential, which together promote enhanced cellular uptake, improved colloidal stability, and efficient drug delivery to target cells. In contrast, F2 (Tween 60) produced larger vesicles and, while it demonstrated the highest entrapment efficiency, its larger particle size may have reduced internalization rates and thus led to slightly lower cytotoxic effects. F3 (Pluronic F-127) had the smallest vesicles, which typically favors internalization, but its moderate entrapment efficiency and relatively rapid initial drug release may affect the duration and potency of cellular drug exposure. F4 (Brij 52) offered a balance between size, stability, and entrapment, and its zero-order release provided the most constant exposure, potentially explaining the moderate cytotoxicity observed.

Thus, the biological performance of each formulation can be explained by the interplay of particle size (impacting cellular uptake and biodistribution), negative zeta potential (governing stability and circulation), entrapment efficiency (controlling delivered drug dose), and release kinetics (modulating the duration and constancy of drug exposure) [17]. Integrating these data demonstrates how physicochemical tuning of niosomes directly translates to differences in therapeutic efficacy across the tested cancer cell lines.

TEM analysis confirmed the morphological integrity and nanometric scale of all niosomal constructs, further underscoring their suitability for biomedical applications. Importantly, the in vitro cytotoxicity assays demonstrated that all niosomal formulations improved the anticancer efficacy of osimertinib compared to the free drug, with Span 60-based niosomes eliciting the greatest reduction in cell viability across multiple cancer cell lines. This suggests that vesicle architecture not only preserves drug payload but also enhances cellular delivery and cytotoxic potential [12].

Collectively, these results validate the rationale for leveraging surfactant diversity in nano-niosomal engineering as a means of fine-tuning drug release and therapeutic action [12]. The study provides a robust framework for the rational design of niosomal carriers, supporting the advancement of targeted and sustained delivery strategies for hydrophobic anticancer agents like osimertinib. Moving forward, in vivo studies are warranted to further elucidate the pharmacokinetic, biodistribution, and safety profiles of these optimized niosomal systems, paving the way for potential translation into clinical oncology practice.

DLS: dynamic light scattering

EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor

HLB: hydrophilic-lipophilic balance

PBS: phosphate-buffered saline

TEM: transmission electron microscopy

The authors gratefully acknowledge the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Saudi Arabia, for generously providing the cell lines used in this study.

S Alhabardi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Project administration. A Almurshedi: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. S Alnassar: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. S Alshabanah: Data curation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. NA: Resources, Investigation. A Alotaibi: Validation, Data curation. LA: Software, Formal analysis. S Alahmari: Resources, Investigation. A Alanteet: Resources, Investigation. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1124

Download: 19

Times Cited: 0