Affiliation:

1Núcleo de Pesquisa em Doenças Crônicas não Transmissíveis (NUPEC), School of Nutrition, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador 40110-150, Brazil

Email: jotafc@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7957-0844

Affiliation:

2Department of Rheumatology, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana 44036-900, Brazil

3Novaclin, Grupo CITA, Salvador 40296-210, Brazil

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2155-5798

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2025;3:1007112 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2025.1007112

Received: November 03, 2025 Accepted: November 27, 2025 Published: December 09, 2025

Academic Editor: Joan M. Nolla, University of Barcelona, Spain

The article belongs to the special issue Complementary and Integrative Medicine in Rheumatology: Evidence, Therapies, and Clinical Impact

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compound whose biological properties have been linked to modulation of oxidative stress, cytokine signaling, and bone metabolism. Given the central role of oxidative and inflammatory mechanisms in rheumatic diseases, lycopene has emerged as a potential nutraceutical adjunct. This narrative review summarizes current evidence regarding lycopene supplementation and its effects on rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders, integrating clinical, preclinical, and mechanistic data into a single comprehensive synthesis. A literature search was conducted in PubMed, SciELO, and LILACS up to July 2024, focusing on studies evaluating lycopene in rheumatic or musculoskeletal contexts. Three human studies met the inclusion criteria, all conducted in postmenopausal women, and demonstrated beneficial effects on bone metabolism and oxidative stress markers without adverse effects. Additional experimental evidence supports lycopene’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and bone-protective actions, reinforcing its potential biological relevance in rheumatology. Overall, the available evidence suggests that lycopene may represent a promising, safe, and accessible adjunct for oxidative stress modulation and bone preservation, particularly in osteoporosis. However, the magnitude and durability of these effects remain to be clarified in larger, well-designed randomized trials

Rheumatic diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and oxidative stress, processes that collectively contribute to joint damage, tissue degeneration, and bone loss. Inflammation-driven reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) exacerbate synovial inflammation, osteoclast activation, and cartilage degradation [1].

Lycopene is a non-provitamin A carotenoid widely found in red-colored fruits and vegetables such as tomatoes, watermelon, pink grapefruit, and papaya. It is the most abundant carotenoid in human plasma, accounting for approximately 30–50% of total circulating carotenoids [2]. Structurally, lycopene consists of 11 conjugated double bonds that confer potent singlet oxygen-quenching and free radical scavenging capacity—approximately twice that of β-carotene [3].

Accumulating evidence suggests that diets rich in lycopene are associated with reduced inflammation, improved endothelial function, and lower risks of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [4]. Given the shared mechanisms of oxidative stress and inflammation across systemic inflammatory diseases, there is increasing interest in its potential applications within rheumatology. This review integrates clinical, experimental, and mechanistic evidence regarding lycopene supplementation in rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders, focusing on bone and connective tissue homeostasis.

A structured literature search was performed in PubMed, SciELO, and LILACS databases up to July 2024 using the terms “lycopene”, “rheumatic diseases”, “osteoporosis”, “autoimmune diseases”, “oxidative stress”, and “inflammation”. No language restrictions were applied. Inclusion criteria were: (1) clinical or preclinical studies evaluating lycopene supplementation in rheumatic or musculoskeletal contexts; (2) trials with defined outcomes related to inflammation, oxidative stress, or bone metabolism; and (3) reviews or meta-analyses exploring carotenoids and rheumatologic implications. Studies not assessing lycopene or without rheumatologic relevance were excluded. This article is a narrative review; therefore, no systematic review methodology or PRISMA framework was applied. Three human studies met the inclusion criteria for direct evaluation in rheumatic contexts [5–7]. Additional mechanistic and experimental evidence was incorporated to contextualize and complement the interpretation of the clinical data.

Lycopene can neutralize singlet oxygen and scavenge superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, or peroxynitrite radicals to prevent lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation [3, 8]. By upregulating antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase, lycopene also reduces malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and nitric oxide itself [9].

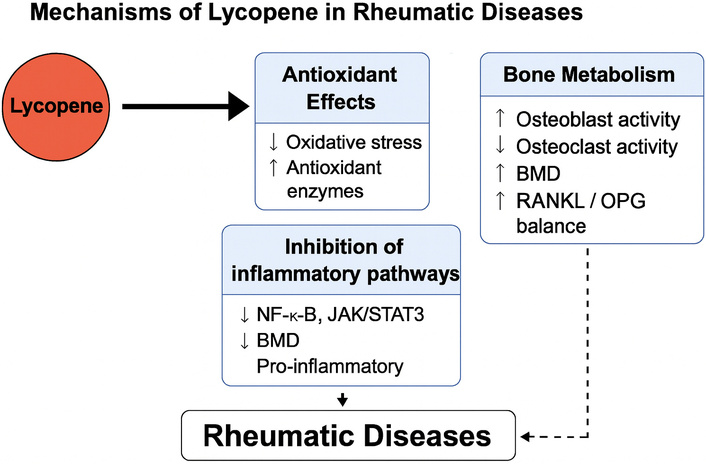

Inflammation-related gene expression is modulated at the cellular level by lycopene. It inactivates NF-κB, JAK/STAT3, and MAPK signaling pathways, leading to reduced production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [10]. In synoviocytes—synovial cells obtained from rheumatoid arthritis patients, lycopene attenuates cytokine-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory activation, improving cell viability [11]. These antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms relevant to rheumatic diseases are summarized in Figure 1.

Mechanisms of lycopene in rheumatic diseases. Lycopene exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects by scavenging reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) and activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, with subsequent upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes and inhibition of inflammatory signaling cascades, including NF-κB, JAK/STAT3, and MAPK, resulting in reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6). In bone tissue, lycopene enhances osteoblast activity via RUNX2 and ERK1/2 and suppresses osteoclastogenesis through RANKL/OPG modulation, contributing to improved bone mineral density (BMD) and preservation of trabecular microarchitecture. Together, these mechanisms support the potential role of lycopene as a nutraceutical adjunct in osteoporosis and other rheumatic conditions.

It also promotes osteoblast differentiation and prevents osteoclast formation. It increases the activity of bone formation markers like alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP), while decreasing that of resorption indices such as N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx) and β-C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX-I) [5–7]. In addition to these mechanisms, population-based evidence further supports a clinically relevant role for lycopene in skeletal protection, as higher dietary intake has been associated with reduced risk of hip fracture in long-term observational data [12]. Experiments on ovariectomized rats showed that feeding them extra lycopene preserved trabecular micro-structure and raised bone mineral density (BMD), findings that are consistent with the central role of the OPG/RANKL/RANK system in metabolic bone diseases [13–16].

The clinical studies evaluating lycopene supplementation in musculoskeletal and rheumatic contexts are summarized in Table 1. All available human interventional data come from postmenopausal women.

Studies on lycopene supplementation in rheumatic and musculoskeletal conditions.

| Author, Year | Study design/Country | Population/n | Lycopene dosage and duration | Main outcomes | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russo et al., 2020 [5] | Pilot prospective clinical study, Italy | Postmenopausal women (n = 39) | Tomato sauce (1.3 mg/50 g) daily for 3 months | A significant bone density loss was detected in control and not in lycopene group. Greater bone alkaline phosphatase reduction after lycopene. | None |

| Meeta et al., 2022 [6] | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial, India | Postmenopausal women (n = 108; lycopene n = 60; placebo n = 48) | Lycopene 8 mg/day for 6 months | ↓ PINP; ↑ serum lycopene; ↓ β-CTX-I (non-significant); improved antioxidant status | None |

| Mackinnon et al., 2011 [7] | Randomized controlled intervention study, Canada | Postmenopausal women (n = 60; lycopene interventions vs. control diets) | Tomato juice/capsules providing 30–70 mg/day for 4 months | ↑ antioxidant capacity; ↓ oxidative stress; ↓ NTx. | None |

β-CTX-I: β-C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen; BMD: bone mineral density, n: number of participants; NTx: N-telopeptide of type I collagen; PINP: procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide; ↑: increase; ↓: decrease.

In a pilot prospective clinical study in Italy, Russo et al. [5] evaluated 39 postmenopausal women who consumed 150 mL/day of tomato sauce (providing approximately 1.3 mg of lycopene in each 50 g of tomato sauce) for three months. The intervention led to a significant bone density loss in control, but is was not seen in lycopene group. In addition, a greater bone alcaline phosphatase reduction after interventio was also confirmed.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in India, Meeta et al. [6] assigned 108 postmenopausal women to receive either 8 mg/day of lycopene (LycoRed®) or placebo for six months. The lycopene group demonstrated a significant decrease in serum PINP, indicating enhanced bone formation, along with improved antioxidant capacity. β-CTX-I showed favorable but non-significant trends, consistent with an early biochemical response preceding measurable structural bone changes.

In a prospective controlled study from Canada, Mackinnon et al. [7] investigated 60 postmenopausal women assigned to receive regular tomato juice (30 mg/day), lycopene-rich tomato juice (70 mg/day), lycopene capsules, or a control beverage for four months. Lycopene supplementation resulted in increased total antioxidant capacity and reductions in oxidative stress markers and N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx). Changes in β-CTX-I and BMD were small and not statistically significant, indicating that short-term supplementation preferentially affects oxidative stress and bone resorption rather than producing immediately detectable effects on bone mass.

The biological logic behind lycopene supplementation in rheumatic disease is supported not only by mechanistic evidence but also by experimental and clinical findings (summarized in Figure 1). Rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and osteoarthritis are maintained by continuous oxidative stress arising from local or systemic inflammation. This situation results in joint destruction or bone destruction [1]. Lycopene, whose antioxidant activity includes efficient quenching of free radicals and singlet oxygen [3, 8], directly intercepts these pathways at a cellular level through anti-inflammatory responses documented in animals as well as in cells in culture. Moreover, it is able to stimulate endogenous antioxidant defenses, including SOD and catalase [9], which provides additional protection.

In addition to its redox activity, lycopene has widespread impacts on inflammatory signaling pathways. Inhibition of NF-κB and STAT3 pathways reduces proinflammatory cytokine transcript levels such as TNF-α and IL-6 [10, 11], which are key mediators of rheumatic disease activity. These anti-inflammatory effects are consistent with those seen in traditional anti-rheumatic therapies that act as cytokine network inhibitors. Lycopene also upregulates Nrf2, promoting antioxidant response element activity and cellular detoxification. Together, these actions suggest that lycopene not only prevents oxidative damage but may also influence immune signaling and, potentially, disease course.

Experimental models provide insight into the magnitude of these effects. In vitro, lycopene consistently reduces oxidative stress markers, diminishes cytokine signaling, and promotes osteoblast activity while inhibiting osteoclast differentiation compared with controls [9, 11]. In ovariectomized rats, lycopene supplementation restores bone microarchitecture, increases BMD, and modulates RANKL/OPG balance—specifically downregulating RANKL and upregulating OPG, thereby reducing osteoclastogenesis [13, 16]. These changes parallel those observed with antiresorptive therapies, although typically at a smaller magnitude.

The human studies included within this review provide a body of complementary data. Improvements in oxidative stress parameters and biochemical markers related to bone turnover have been reported across studies [5–7]. Russo et al. [5] observed reductions in oxidative stress and BAP, but did not include a placebo group and did not report formal between-group differences in BMD. Meeta et al. [6] demonstrated a significant decrease in PINP, while changes in β-CTX-I were non-significant and should be interpreted as early biochemical trends. Mackinnon et al. [7] reported significant reductions in oxidative stress and NTx; while bone formation markers showed no statistical changes, these non-significant findings may be considered trends rather than definitive effects.

Long-term observational data indicate that higher plasma lycopene concentrations and dietary carotenoid intake are independently associated with greater BMD and a reduced risk of hip fracture in older adults [12]. This association suggests that long-term lycopene intake may contribute to skeletal health. Although not substituting for randomized trials, these findings support biological plausibility.

Lycopene’s systemic advantages are not limited to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Dietary lycopene improves endothelial function, reduces LDL oxidation, and enhances nitric oxide bioavailability [14, 15]. Moreover, population-based data indicate that higher carotenoid intake is associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome [17], and longitudinal studies in individuals with metabolic syndrome demonstrate that elevated serum carotenoid concentrations, particularly trans-lycopene and total lycopene, are independently associated with reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [18].

Carotenoid supplementation as a class has been associated with reductions in inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6 in randomized clinical trials [19], supporting a plausible mechanistic link between carotenoid intake and modulation of systemic inflammation. In this context, oxidative stress has been implicated in chronic pain and fatigue syndromes including fibromyalgia [20] and in immune-mediated rheumatic diseases [21]. Lycopene’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties may, therefore, exert indirect effects on somatic symptom burden in these disorders, although specific interventional trials are still lacking.

Nevertheless, despite these encouraging findings, the current evidence has some distinct shortcomings. The three human studies were small, short-term, and limited to postmenopausal women [5–7]. There are currently no randomized clinical trials specifically evaluating lycopene in inflammatory rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or psoriatic arthritis; existing trials focus mainly on osteoporosis and bone health. Furthermore, differences in dose and duration of therapy (3.9–70 mg/day), as well as the form of administration, influence outcome measures. Future work needs to consider baseline characteristics, standardized dosing, more diverse populations, and functional outcomes such as pain severity and inflammation.

Lycopene’s outstanding safety record suggests that it may be a beneficial nutraceutical supplement in rheumatology. All human trials encountered no side effects [5–7], and nutritional data support tolerability even at higher doses [4, 22]. Given its dual action as an antioxidant and inhibitor of bone resorption, lycopene might complement traditional medical treatments.

Finally, the biological and clinical evidence reviewed here suggests that lycopene may be considered a relevant compound at the intersection of rheumatology, nutrition and bone metabolism, offering a physiologically meaningful protective agent against oxidative and inflammatory damage. The consistency across mechanistic, animal, and clinical data strongly supports conducting large-scale randomized controlled trials to determine efficacy, optimal dosing, and broader therapeutic applications.

Lycopene is a naturally occurring carotenoid with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, contributing to bone preservation and potentially mitigating oxidative stress in rheumatic diseases. Current evidence—though limited and largely derived from studies in postmenopausal women—suggests beneficial effects on bone metabolism and systemic inflammation, particularly in osteoporosis. Given its favorable safety profile and accessibility, lycopene represents a promising nutraceutical adjunct in the integrative management of musculoskeletal health. However, the existing human trials are small and not designed to evaluate inflammatory rheumatic diseases, and therefore, the findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Larger, well-controlled studies are warranted to establish optimal dosage, long-term effects, and applicability across diverse rheumatic conditions, including inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

BAP: bone-specific alkaline phosphatase

BMD: bone mineral density

NTx: N-telopeptide of type I collagen

PINP: procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide

RNS: reactive nitrogen species

ROS: reactive oxygen species

SOD: superoxide dismutase

The authors thank colleagues from Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) for their valuable discussions that contributed to the development of this review. During the preparation of this work, the authors used AI to assist in language refinement, structural organization, and reference formatting. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and edited the content to ensure accuracy, originality, and intellectual contribution. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article.

JFdC: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ATAM: Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

Jozélio Freire de Carvalho, who is the Associate Editor and Guest Editor of Exploration of Musculoskeletal Diseases, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. Ana Tereza Amoedo Martinez declares no competing financial or personal interests that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1326

Download: 17

Times Cited: 0