Affiliation:

1Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation (AIHI), Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia

†These authors share the first authorship.

Email: khalia.ackermann@mq.edu.au

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9868-9456

Affiliation:

2Faculty of Medicine, Health, and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia

†These authors share the first authorship.

Affiliation:

2Faculty of Medicine, Health, and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia

3Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Sydney, New South Wales 2145, Australia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5566-4769

Affiliation:

1Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation (AIHI), Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1642-142X

Explor Digit Health Technol. 2026;4:101186 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edht.2026.101186

Received: July 08, 2025 Accepted: December 23, 2025 Published: February 13, 2026

Academic Editor: Robert S. H. Istepanian, Imperial College, UK

Background: Sepsis is a major cause of disease worldwide. Mobile applications (apps) have been developed to assist clinical practice. Current evidence evaluating such apps is diverse. This scoping review aimed to map currently available literature investigating the usage of mobile apps for sepsis-related healthcare. This will highlight evidence gaps, and areas for future innovation and app development.

Methods: Databases MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched in June 2023 (updated in July 2024). Studies containing original research investigating mobile apps for sepsis-related healthcare were included and analysed in three categories identified from the primary purpose of the app: (1) education and awareness, (2) clinical assistance, and (3) biomarker or pathogen detection.

Results: A total of 1,755 studies were identified and 27 included following screening, of which 19 (70%) were published in 2020 or later. Most of the 27 studies investigated apps for clinical assistance (70%, n = 19). These apps were diverse, acting as digital solutions for data collection (n = 2), triage (n = 6), clinical guideline access (n = 5), alert delivery (n = 1), and outcome prediction (n = 5). There were five apps (19%) used to assist biomarker or pathogen detection. Of these, most (80%, n = 4) mobile apps were used to detect and quantify colorimetric signals in combination with assays, and all five apps had attachments necessary for laboratory processes. Lastly, three apps (11%) were designed to enhance education and awareness, two targeting medical education and one targeting public awareness.

Discussion: Mobile applications offer innovative and exciting digital solutions for biomarker detection, education, and clinical support in sepsis-related healthcare. Current literature is highly heterogenous and rapidly developing.

Mobile health (mHealth) was defined in the early 2000s as ‘mobile computing, medical sensor, and communications technologies for healthcare’ [1–3]. Development of smartphone technology has led to the rapid proliferation of the use of mobile applications (apps) to support healthcare [2, 4–9]. As general evidence for the clinical benefits of mHealth is limited, mHealth solutions should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis [2, 10].

Most healthcare professionals own smartphones and have reported their usefulness in clinical practice [7, 8]. Some examples of mobile app use by clinicians include providing portable and easy access to clinical calculators, health records, clinical workflows and guidelines, medical education, and health communication [4, 6, 10–13]. Mobile apps are also being developed for healthcare patients, with example uses including promoting behaviour change, facilitating self-management of health conditions, providing accessible patient education, and improving patient quality of life [14–18].

Mobile apps are one of many digital technologies aimed at supporting sepsis-related healthcare and improving health outcomes [19]. Sepsis, defined in 2016 as life-threatening organ dysfunction in the presence of suspected infection [20], is a leading cause of disease worldwide [21]. Globally, an estimated 48.9 million cases of sepsis were reported in 2017, and 11 million sepsis-related deaths [21]. Innovative and novel mobile apps have been recently developed for diverse purposes in sepsis healthcare, such as improving sepsis education, detection, and point-of-care testing [22–24]. Such interventions represent promising improvements in healthcare. Mobile app use in healthcare is also becoming increasingly prevalent in low-resource settings [9], which geographically coincide with the majority of the sepsis burden [21]. In such settings, mobile apps have been shown to benefit healthcare professionals and patients, with advantages such as good acceptability, usability, health and program outcomes, technical infrastructure, data quality, and low costs [5].

Due to the diversity and rapid development of mobile apps for sepsis, the literature exploring these apps is likely just as varied, making it challenging to understand the extent of the available evidence. By mapping the available literature on mobile apps for sepsis-related healthcare, the results of this scoping review will provide a comprehensive overview of the research field to identify and promote innovation, and facilitate further app development, policymaking, and future research. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to (i) characterise novel and innovative uses of mobile apps for sepsis-related healthcare, (ii) summarise study outcomes, targeted populations and investigated mobile apps, and (iii) determine mobile app use across high and low resource settings for sepsis-related healthcare.

The scoping review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; see Supplementary material 1 for completed checklist) [25] and the five-step framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [26].

A search strategy containing sepsis (e.g., ‘sepsis’) and mobile app-related terms (e.g., ‘mhealth’) was iteratively designed and piloted with the assistance of a clinical librarian. Complete search strategies for all databases can be found in Supplementary material 2. The ‘health apps’ validated search filters created by the United Kingdom’s NICE (National Institute for Healthcare and Excellence) [27] were used for MEDLINE and Embase. The final search strategy was used to search six databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane, Scopus, and Web of Science in June 2023. The search was updated in July 2024. The search was restricted to human studies published in English, and no date limits were applied. Reference lists of relevant literature were manually examined for any additional studies.

The search results were imported into Covidence [28], a web-based software platform that streamlines the systematic review process, for duplicate removal and screening. Using the eligibility criteria below, title, abstract, and full text screening were conducted independently by two reviewers (KA, DK), with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (LL). Before screening, 50 studies were included in a title and abstract screen pilot to ensure eligibility criteria clarity among the review team.

Studies were included if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (i) investigated mobile apps used for any form of sepsis-related healthcare, and (ii) published in the English language or with an English translation readily available. Sepsis-related healthcare could be the primary or secondary purpose of the app. Mobile apps were defined as self-contained software packages available for use on a mobile device. Web apps were not included. A mobile device was defined as a hand-held device that is functional without being connected to electricity or network outlets. Smartwatches were excluded.

Studies were excluded if they met one or more of the following: (i) did not include original research or were case reports, (ii) involved non-human investigations, and (iii) investigated standard in-built phone apps such as SMS and phone calls. Studies that contained both non-human and human investigations were included, with data extracted and reported on from only the human investigations.

A data charting form was designed in Microsoft Excel (Version 2411 Build 16.0.18227.20082) in accordance with the review aims and objectives. Excel was chosen as it was accessible and familiar to both reviewers (KA, DK) and allowed the design of logical and easy-to-use data extraction tables. A single reviewer (DK) piloted this form, which was checked by a second reviewer (KA). Form amendments, additions, and exclusions were made following discussions between reviewers (KA, DK, LL). The form extracted information on the study characteristics, app characteristics, and investigated outcomes. Study designs were classified as previously reported [29], and modified to include ‘Testing and Development’; defined as studies detailing the design, optimisation, and validation of apps through laboratory or simulated settings. Studies that incorporated multiple different study designs were classified based on their primary aim. Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (KA, DK), with any discrepancies discussed with a third reviewer (LL).

Results from the data extraction were analysed by narrative synthesis and through frequency counts and tables. Studies were categorised based on the primary purpose of the mobile app investigated within the paper. Three main categories were identified: 1) clinical assistance apps aimed at supporting healthcare professionals in the clinical setting, 2) biomarker or pathogen detection apps aimed at identifying biomarker or pathogens through innovative point-of-care or laboratory tests, and 3) education and awareness apps aimed at improving knowledge and education. Within the clinical assistance category there were five sub-groups: (i) data collection apps aimed at improving the collection of healthcare data, (ii) triage apps aimed at providing a digital triage service for patients entering clinical care, (iii) guideline or management pathway apps aimed at providing portable and quick access to clinical guidelines or management pathways, (iv) alert delivery apps aimed at providing real-time monitoring or alerts, and (v) prediction tool apps aimed at improving the prediction or outcomes or risk of an outcome. Prediction tools could be rule-based or machine learning (ML) models. Study outcomes in the clinical assistance category were grouped iteratively as needed for presentation in tables (see Supplementary material 3 for group breakdown).

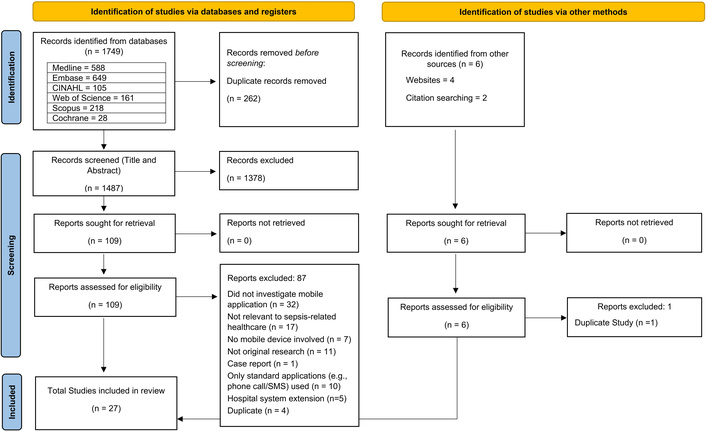

A total of 1,749 records were identified through database searches, and six from other sources. Following removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, 115 full texts were reviewed, and 27 [22–24, 30–53] studies were included. The full study selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. See Supplementary material 4 and 5 for details of the included studies.

PRISMA flow diagram summarising the study selection process. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Adapted from Page et al. [54]. © 2021, The Author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.

All studies were published in 2015 onwards. Most studies (19/27, 70%) were published in the year 2020 or later [22–24, 30, 31, 34–38, 41, 43–47, 49, 50, 52]. Of the 27 studies, 22 were journal articles (81%), four were abstracts (15%) [35, 42, 50, 52], and one was a preprint article (4%) [31]. Table 1 summarises the study characteristics of the included literature.

Summary of characteristics of included studies (for full details, see Supplementary material 4 and 5).

| Study characteristics | App purpose | Total number of studiesn (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and awarenessn (%) | Clinical assistancen (%) | Biomarker or pathogen detectionn (%) | ||

| Total | 3 | 19 | 5 | 27 |

| Study design | ||||

| Testing and development | 0 | 1 (5) | 5 (100) | 6 (22) |

| Survey/interview | 1 (33) | 2 (11) | 0 | 3 (11) |

| Pre/post study | 2 (67) | 4 (21) | 0 | 6 (22) |

| Cohort study | 0 | 9 (47) | 0 | 9 (33) |

| Interrupted time series | 0 | 3 (16) | 0 | 3 (11) |

| Continent of studya | ||||

| North America | 0 | 5 (26) | 1 (20) | 6 (22) |

| South America | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Europe | 0 | 2 (11) | 1 (20) | 3 (11) |

| Africa | 1 (33) | 7 (37) | 0 | 8 (30) |

| Asia | 1 (33) | 1 (5) | 0 | 2 (7) |

| NR | 0 | 4 (21) | 3 (60) | 7 (26) |

| Participant population | ||||

| Paediatric patients | 0 | 6 (32) | 0 | 6 (22) |

| Neonatal patients | 0 | 3 (16) | 0 | 3 (11) |

| Adult patients | 0 | 4 (21) | 0 | 4 (15) |

| All agesb | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (20) | 2 (7) |

| Both patients and healthcare professionals | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Healthcare professionalsc | 3 (100) | 4 (21) | 1 (20) | 8 (30) |

| NR | 0 | 0 | 3 (60) | 3 (11) |

| Number of participants | ||||

| 1–10 | 0 | 0 | 2 (40) | 2 (7) |

| 11–100 | 2 (67) | 4 (21) | 0 | 6 (22) |

| 101–10,000 | 1 (33) | 6 (32) | 0 | 7 (26) |

| 10,001–100,000 | 0 | 3 (16) | 0 | 3 (11) |

| 100,001+ | 0 | 2 (11) | 0 | 2 (7) |

| NR or variabled | 0 | 4 (21) | 3 (60) | 7 (26) |

NR: not reported. a: Country breakdown in each continent: North America (United States of America and Canada), Europe (United Kingdom, Scotland, and Denmark), Africa (Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Uganda, and Kenya), South America (Brazil), Asia (South Korea and Thailand). b: Includes studies in which an age range was not specified. c: Healthcare professionals included clinicians, nurses, healthcare staff, medical laboratory staff, or experts in sepsis-related healthcare. d: Some studies varied participant numbers by study section, with no total number provided.

The characteristics of the mobile apps investigated in the included studies are summarised in Table 2 (see Supplementary material 4 and 5 for details of each study). Of the 27 studies, 26 (96%) investigated apps intended for use by healthcare professionals (including both clinical staff and/or medical laboratory scientists), and one (4%) for use by the general public [44].

Characteristics of the mobile applications investigated in the included studies (See Supplementary material 5 for further details).

| Application characteristics | App purpose | Total number of studiesn (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and awarenessn (%) | Clinical assistance toolsn (%) | Biomarker or pathogen detectionn (%) | ||

| Total | 3 | 19 | 5 | 27 |

| Targeted users | ||||

| Healthcare professionalsa | 2 (67) | 19 (100) | 5 (100) | 26 (96) |

| General public | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Application platform | ||||

| iOs and Android | 1 (33) | 8 (42) | 0 | 9 (33) |

| Android only | 2 (67) | 5 (26) | 5 (100) | 12 (44) |

| NR | 0 | 6 (32) | 0 | 6 (22) |

| Application device | ||||

| Tablet | 0 | 3 (16) | 1 (20) | 4 (15) |

| Smartphone | 3 (100) | 13 (68) | 4 (80) | 20 (74) |

| NR | 0 | 3 (16) | 0 | 3 (11) |

| External hardware associatedb | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 6 (32) | 5 (100) | 11 (41) |

| No | 3 (100) | 13 (68) | 0 | 16 (59) |

| Part of a larger intervention | ||||

| Yes | 1 (33) | 9 (47) | 0 | 10 (37) |

| No | 2 (67) | 10 (53) | 5 (100) | 17 (63) |

NR: not reported. a: Includes studies where the targeted user was not explicitly reported but assumed to be healthcare professionals from the article context. b: External hardware associated refers to if any external equipment was used in conjunction with the mobile application.

Most (17/27, 63%) apps were standalone, however, one (4%) education and awareness app was part of a larger educational program [22], and nine (33%) clinical assistance apps were integrated into a larger system (such as clinical decision support systems, quality improvement programs, and educational programs) [24, 31, 35, 39, 41, 43, 48–50]. Similarly, while most apps (16/27, 59%) operated as only a mobile app, 11 (41%) had additional external components required for use. All five (19%) apps for biomarker and pathogen detection had attachments required for laboratory processing [23, 32, 40, 51, 53], and six (22%) clinical assistance apps had vital sign measurement or tracking tool attachments [24, 31, 38, 43, 49, 50].

Mobile apps serving as tools for clinical assistance were investigated in 19 of the total 27 studies (70%), Of the 19 studies, two investigated apps for data collection [35, 36], six for digital triage [24, 31, 34, 43, 49, 50], five for clinical guidelines or pathways [39, 41, 42, 45, 48], one for alert delivery [38], and five for prediction [33, 37, 46, 47, 52] (Table 3).

Studies of clinical assistance applications (see Supplementary material 4 and 5 for further details).

| Application purpose | Number of studies | Application name(s) | Country of study | Outcomes measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | 1 abstract [35]1 article [36] | NeoTree [35, 36] | Malawi [35]Zimbabwe [36] | Completeness of data capture and coverage [35, 36]Turnaround time for test results [36]Provision of data for quality improvement [36] |

| Digital triage | 4 articles [24, 34, 43, 49]1 abstract [50]1 pre-print [31] | Smart Triage [31, 43, 49, 50]Pedicmeter [34]NR [24] | Uganda [24, 31, 43, 49, 50]Kenya [31]Thailand [34] | Mortality [31, 43]Timely treatment [24, 31, 43, 50]Diagnosis validity [34]Admission, readmission, and length of stay [31]Feasibility and cost [43, 49]User acceptance [34, 49] |

| Guideline or clinical pathway access | 4 articles [39, 41, 45, 48]1 abstract [42] | PedsGuide [39, 48]IWK app [45]NR [41, 42] | US [39, 41, 48]Canada [45]NR [42] | Bundle and bundle element completion [42]App usage [39, 41, 48]Usability [41, 48]Mortality and length of stay [45]Appropriate antimicrobial prescribing [45] |

| Alert delivery | 1 article [38] | Sensium [38] | UK [38] | Time to alert acknowledgement [38]Alert action taken [38] |

| Prediction tool | 4 articles [33, 37, 46, 47]a1 abstract [52] | POTTER [33, 47]aPOTTER-ICU [37]aTOP [46]aNR [52] | ACS-NSQIPa,b [33, 37, 47]ACS-TQIP a,b [46]Scotland [52] | Mortality [33, 46, 47]aMorbidity (non-infectious) [33, 46, 47]aMorbidity (sepsis and infections) [33, 46, 47]aICU admission [37]aReferral for pediatric hospitalisation [52] |

US: United States; NR: not reported; UK: United Kingdom; ACS-NSQIP: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; ACS-TQIP: American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program; POTTER: Predictive Optimal Trees in Emergency Surgery Risk; ICU: intensive care unit; TOP: trauma outcome predictor. a: These predictive tools were designed using the machine learning technique ‘optimal classification trees’. b: ACS-NSQIP and ACS-TQIP data comprise surgical data from participating hospitals, which may be set across numerous countries.

Both studies investigating apps for data collection were cohort studies and investigated the use of the NeoTree application in African countries (Zimbabwe or Malawi). Outcomes included completeness of data capture and coverage of data capture, test result turnaround time, and the use of data for quality improvement initiatives in the local community (Table 3). Similarly, most studies (4/6, 67%) [31, 43, 49, 50] investigating data triage apps also investigated the use of the Smart Triage app in African countries (Uganda and Kenya), with outcomes including mortality, timely treatment, feasibility, cost, user acceptance, admissions, readmissions, and length of stay (Table 3).

Of the five studies investigating apps for guideline or clinical pathway access, two (40%) [39, 48] investigated PedsGuide (part of the Reducing Excessive Variation in Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) program). Other studies investigated apps providing access to antimicrobial stewardship guidelines (1/5, 20%) [45], the sepsis-6 protocol (1/5, 20%) [42], and organisational clinical guidelines (1/5, 20%) [41]. Outcomes included bundle completion, app usage, usability, mortality, length of stay, and appropriate antimicrobial prescribing (Table 3). A mobile app used to deliver alerts from wearable sensors was investigated in one study [38], with outcomes including time to alert acknowledgement and what alert action was taken.

Of the studies investigating mobile apps for outcome prediction, none were specific to sepsis [33, 37, 46, 47, 52]. Rather, one app [52] investigated sepsis as one of multiple condition-specific pathways, and four apps [33, 37, 46, 47] investigated sepsis as one of the many patient morbidities identified by the app for emergency surgery or trauma patients. All five studies investigated the accuracy of the apps for predicting patient outcomes (Table 3). Most (4/5, 80%) utilised a ML technique called Optimal Classification Trees (OCTs) [33, 37, 46, 47]. The mobile apps presented in these four studies used the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) or American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (ACS-TQIP) datasets, including multi-national data from participating hospitals (Table 3), for both training and validation of ML models. Input variables included patient demographics, procedure or presentation characteristics, comorbidities, and vital signs or laboratory results.

Mobile apps for biomarker or pathogen detection systems within sepsis-related healthcare were investigated by five studies (5/27, 19%) [23, 32, 40, 51, 53]. Of the five apps, four used smartphone cameras to detect and quantify colorimetric signals from assay reactions to identify biomarker or pathogens in blood or urine samples (Table 4). The remaining study investigated an app designed to provide accessible guidelines and a data entry platform for the Multiplex Blood Culture Test (Table 4) [53]. All five studies were testing and development studies and investigated outcomes related to the optimisation of assay protocols [23, 40, 51], accurate detection of the appropriate biomarker or pathogen [23, 32, 40, 51, 53], time to measurement or data entry [32, 53], and the usability of the app [53].

Characteristics of biomarker/pathogen detection applications.

| Study | Application role | Associated external hardware | Biomarkers or pathogens detected | Biological specimen used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alba-Patiño et al., 2020 [23] | Colorimetric signal detection and quantification | Paper-based biosensor with optimised nanoprobes, assay solutions | Interluekin-6 | Blood |

| Barnes et al., 2018 [32] | Colorimetric signal detection and quantification | LAMP lysis and reaction solutions, 36-well plate, heat block, and LED light source | Bacteria(Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella enteritidis, Yersina pseudotuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae) | Urine |

| Kim et al., 2017 [40] | Colorimetric signal detection and quantification | Immunoassay and biochemical assay hybrid strip and solutions, plastic cartridge, and smartphone attachment | Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, lactate | Blood |

| Russell et al., 2019 [51] | Colorimetric signal detection and quantification | Janus particles, immunoassay solutions, filter paper | Procalcitonin | Blood |

| Samson et al., 2016 [53] | Guidelines for Multiplex Blood Culture Test (MuxBCT) and data entry | Bluetooth barcode scanner | Bacteria(not specified) | Blood |

LAMP: loop-mediated isothermal amplification; LED: light emitting diode.

The search identified three studies (3/27, 11%) investigating apps providing education and awareness for sepsis-related healthcare, two with a pre-post study design [22, 30] and one survey/interview [44]. Studies investigated apps targeting healthcare providers [22, 30] and the general public [44]. Outcomes included user knowledge [22, 30], confidence and accuracy in sepsis assessments [22], validation of app content [44], and user experiences [30].

This scoping review comprehensively mapped the literature investigating mobile apps for sepsis-related healthcare. The included studies investigated a diverse range of innovative mobile apps designed for education and awareness, biomarker or pathogen detection, and clinical assistance. All studies were published in the last 10 years (since 2015), with over two-thirds (70%) published in 2020 or later. This recent and rapid expansion of the literature indicates a growing interest in sepsis-related mobile apps. However, the study designs of the included studies were cohort, pre-post, interrupted time series, survey or interviews, and testing or development (Table 1). Further studies with a randomised controlled trial design would provide more robust evidence on the effectiveness of mobile apps for improving sepsis-related care.

Smartphone adoption among healthcare professionals has seen significant growth [4, 7]. Over 95% of doctors and nurses own smartphones [7, 8]. Over 90% of doctors and over 50% of nurses find them useful for assisting with everyday clinical practice [7]. Clinicians have reported positives such as improved communication, productivity, and mobility [55, 56]. Most (70%) of the studies included in our review investigated apps for clinical assistance, with 89% of these apps targeted at healthcare professionals (the remaining 2 apps did not report target users). A scoping review published in 2023 [4] reported clinicians used smartphones and mobile apps for communication, clinical decision-making, health records, medical education, referencing, patient monitoring, and time management. Our findings reflected these results, with identified literature investigating apps with uses such as data collection (health records), digital triage, guideline or clinical pathway access, and prediction tools (clinical decision making), education and awareness (medical education), and alert delivery (patient monitoring). However, the rising use of smartphones in clinical practice has also brought serious concerns about the security and privacy of health data [55, 57, 58]. This is especially true for personal devices [55, 57]. Security on personal devices relies largely on user behaviour, as hospitals have no control over the security of clinicians’ smartphones [57]. These concerns must be addressed for mobile apps to be sustainably and successfully integrated into sepsis care pathways.

Mobile apps have also been used by patients for self-management of other health conditions, such as diabetes [15], hypertension [16], and breast cancer [17]. Our findings show current literature on sepsis mobile apps does not investigate apps for patients or the general public. Sepsis survivors often suffer from ongoing sequalae, including physical disabilities, cognitive decline, and poor mental health [59, 60]. Most of the studies included in our review investigate mobile apps designed to improve sepsis care during the acute disease stage. This is often while patients are hospitalised and may explain why few of the apps we investigated were aimed at patients. However, mobile apps could be used by survivors for rehabilitation or monitoring of sequalae symptoms, highlighting a clear research gap for future studies and app development efforts.

Mobile apps can also provide healthcare professionals with quick access to predictive tools [37, 46]. We included five studies investigating mobile app prediction tools in this review. Four of these investigated apps utilising OCTs, a ML technique [33, 37, 46, 47]. OCTs build easily interpretable models, offering good accuracy and more transparency than other “black box” ML techniques [33, 37, 46]. The “black box” nature of many ML techniques can dissuade clinician trust in model outputs [61]. To successfully implement predictive tools using ML techniques in routine sepsis care, human-centered and economic factors must be considered [61]. Clinician trust and support are therefore critical, highlighting the benefit of developing ML models which are more transparent and interpretable [61].

Other key factors for the successful clinical use of ML models are accuracy and generalisability [61, 62]. A model trained on poor-quality, non-representative data and only validated internally may lead to inaccurate or biased output [61, 62]. In addition, different patient populations, digital infrastructure, clinical practices, sepsis definitions, and available data between health systems limit interoperability [58, 61, 62]. Data harmonisation between hospitals can be complex and costly [62]. Therefore, to be sustainable and scalable, digital solutions should be generalisable to many diverse clinical settings and be able to integrate with different clinical systems and electronic health records [61]. External validation of digital solutions using different data sources or through prospective trials is critical for evaluating this generalisability in diverse real-world settings [61, 62]. In our review, all four studies investigating ML-based predictive tools [33, 37, 46, 47] utilised high quality clinical databases with large sample sizes. Three studies utilised the ACS-NSQIP database [33, 37, 47] and one the ACS-TQIP database [46], splitting the database into training and validation datasets. However, all four studies evaluated their tools through internal validation. While two studies applied the same mobile app to different patient populations, both validation datasets were derived from the same data source used for training [33, 47]. Therefore, while the results of these studies show promise, robust external and prospective validation is needed before they can be implemented clinically.

In addition, none of the mobile apps included prediction tools specific to sepsis-related healthcare. Rather, they included sepsis management as one of many clinical pathways investigated [52], or they investigated morbidity and mortality outcomes, of which sepsis detection was one, for surgical [33, 37, 47] or trauma patients [46]. There are many ML-based prediction tools developed specifically for sepsis available outside of mobile app platforms (e.g., through computers or web-apps) [63–65]. While these tools show promise, many have not been implemented clinically or externally validated [61, 62, 65]. This is likely because the field is still emerging, with most research on ML applications in sepsis occurring since 2014 [66]. The development of mobile interfaces for such sepsis-specific prediction tools and their external and prospective evaluation in clinical settings would be a valuable area for future research.

Early detection of sepsis followed by timely treatment is linked to improved patient outcomes [67]. Mobile apps could potentially reduce the cost, time, and technical complexity needed for biomarker or pathogen detection compared to current systems [23, 32, 51]. Improving point-of-care testing for biomarkers and pathogens with a known association with sepsis may improve sepsis detection. This review identified five studies investigating mobile app-based biomarker or pathogen detection systems, revealing exciting and innovative new approaches to sepsis point-of-care testing. For example, Barnes et al.’s study [32] presents smart-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), a bacterial detection system that performs comparatively with clinical diagnostics at the admitting hospital over a much shorter timeframe. The biomarker detection system reported by Russell et al. [51] detected PCT at clinically relevant concentrations within 13 minutes in whole blood, faster than conventional detection systems. Similarly, Alba-Patiño et al. [23] developed a portable system which detected the biomarker IL-6 in low concentrations in whole blood in 17 minutes.

However, all five studies identified by our search were limited by being testing and development studies with small sample sizes. Potential barriers to real-world implementation should also be considered. Introducing new clinical tests requires investment, as reagents and materials can be costly, staff must be trained, and laboratory space needs to be provided [68]. In the case of mobile app-based detection systems, smartphones will also have to be provided to minimise potential security and contamination risks [57]. While the preliminary experimental results reported are promising, further evaluation and trial data are needed before mobile app-based tools could be integrated into real-world practice.

In low-resource settings, mobile app interventions can provide substantial healthcare worker, patient, and healthcare delivery system benefits [5, 9]. In our review, two apps (NeoTree data collection app [35, 36], and Smart Triage digital triage app [24, 31, 43, 49, 50]) reported app use in low-resource settings in African countries (Zimbabwe, Malawi, Uganda, and Kenya). A 2016 systematic review of 31 articles investigating mobile app use by healthcare professionals in low-resource settings identified four general purposes apps fulfilled [5]. The NeoTree app performed two of these purposes: (i) collected health data at patient visits to facilitate care, and (ii) collected data for surveillance or research [35, 36]. A high coverage and completeness of data collection was achieved by NeoTree, and it was found to be an effective tool for data capture and quality improvement, with clinicians receiving feedback monthly [35, 36]. Smart Triage also fulfilled two purposes: (i) communication between healthcare professionals (including with digital health solutions), and (ii) collect data for surveillance or research [31, 43, 49, 50]. The Smart Triage app was reported to be cost-effective, however, health worker attitudes were mixed [43, 49]. Implementation studies also showed some inconsistent improvements in patient outcomes, such as mortality, time to antimicrobials, and time to treatment with further research needed [31, 43, 50].

Mobile apps can provide a portable, easily accessible, and versatile tool for teaching users skills and knowledge to enhance sepsis-related healthcare [11]. Of the three education and awareness mobile apps our review identified, two studies [22, 30] demonstrated improvement of sepsis knowledge in healthcare professionals following app introduction. The final app by Limeira et al. [44], detailed the design and content validation of an education app during development. A systematic review of 52 studies [11] investigating the use of mobile apps in medical education for any condition or health domain similarly reported that most studies (78.6%, 33/42) found an improvement in knowledge level after app use. Unfortunately, none of the three studies we included [22, 30, 44], evaluated whether their results translated to better patient outcomes in the real world. This highlights a key knowledge gap for future research in sepsis-related healthcare.

Mobile apps are only one part of the broader landscape of digital healthcare. Telehealth and computerised clinical decision support (CCDS) systems are other examples of digital tools being developed to support improved sepsis care [29, 69, 70]. Telehealth describes using technology to enable communication between healthcare providers and patients [69]. A review of 15 studies reported that telehealth has been investigated for use in sepsis care across diverse settings, including the intensive care unit, the emergency department, and post-discharge [69]. However, unlike the diverse purposes of sepsis-related mobile apps reported by our findings, Tu et al. [69] found that telehealth in sepsis care is largely used for facilitating clinician communication.

CCDS systems are designed to support clinicians in disease detection and management and have been evaluated in a diverse range of settings [29, 70]. In our review, mobile apps in the Clinical Assistance category have similar functions to, or could complement, hospital CCDS systems. This is particularly true for those in the Triage, Guideline Access, Alert Delivery, or Prediction categories. A key benefit of mobile device use identified by clinicians is the mobility and flexibility afforded by them for clinical communication or accessing patient records [55, 56]. Using mobile apps in tandem with hospital systems could enhance CCDS communication with clinicians [56, 71]. This is especially valuable for time-sensitive conditions such as sepsis. Clinician interviews and observations of a digital alert embedded in hospitals in England reported that the use of mobile phone apps assisted the utility of digital alerts [71]. ML could further enhance CCDS systems and corresponding mobile apps, especially in the intensive care unit, by integrating and processing extremely large, complex, and real-time datasets [62]. A review of 97 studies reported ML-based CCDS systems in the intensive care unit were mostly used for outcome prediction or prognosis, early identification of clinical events, or detection, monitoring, and diagnosis [62]. Accordingly, all four studies investigating ML-based mobile apps in our review were for the prediction of clinical outcomes.

Importantly, good integration of mobile apps with the wider digital landscape and clinician trust, understanding, and support are fundamental to mobile app success and long-term value in real-world clinical practice [58, 62, 71]. Almost two-thirds of the studies included in our review (17/27) investigated standalone apps that were not part of a larger intervention. Clinicians view good integration and multi-model functionality of digital CCDS and alerts into the complex workflow of the hospitals as very beneficial for sepsis care [71]. Mobile apps that don’t integrate well may increase clinician cognitive load, ultimately leading to distrust and disuse [56, 71]. Human factors, such as clinician experience, patient presentations, staffing ratios, training programs, usability, and clinician trust, can influence the success of digital solutions in sepsis care [58, 71]. Therefore, aside from being well-integrated and functional, mobile apps need to be accessible and user-friendly. Multidisciplinary collaboration and clinician input during app development, testing, and evaluation could enhance app user-experience and encourage clinician investment and support.

Through a comprehensive search strategy, this review summarised the exciting, innovative, and diverse applications of sepsis-related mobile apps being investigated in the literature. The recency and geographical range of the included studies, conducted in countries across five different continents, highlight the value and applicability of mobile apps across diverse settings. Our findings also emphasize areas in need of further research or app development, such as security and privacy, apps aimed at the general public or patients, the use of ML tools, and integration of apps into the wider hospital infrastructure. Furthermore, our review reiterates the need for real-world clinical validation of implemented apps. However, the review has some limitations. Firstly, the search was restricted to studies published in English due to time and language constraints, which may have excluded relevant research published in other languages. Secondly, while searching six large databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane) minimizes the risk of missing relevant studies, studies not indexed would not be included. Thirdly, our review included studies investigating mobile apps but did not search for sepsis-related mobile apps directly (i.e., through an app store). Therefore, it does not necessarily reflect all available mobile apps, only ones investigated in the literature.

Mobile apps for use in sepsis-related healthcare is a recent and rapidly developing field. While the available literature is heterogenous, mobile apps hold considerable promise in transforming diverse aspects of clinical practice. They offer exciting and innovative uses in education, diagnostics, and clinical support, which have the potential to improve clinical workflows and patient outcomes. However, current literature investigating such apps remains preliminary. Key areas for future research were highlighted by this review, including external and prospective validation of apps, the real-world impact of mobile apps on patient outcomes, strategies for successful integration of mobile apps with wider digital infrastructure, and security concerns.

ACS-NSQIP: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

ACS-TQIP: American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program

apps: mobile applications

CCDS: computerised clinical decision support

mHealth: mobile health

ML: machine learning

OCTs: optimal classification trees

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/101186_sup_1.pdf.

The authors would like to thank Mr. Jeremy Cullis, an experienced clinical librarian, for his guidance in developing the final search strategy and translating it to other databases.

KA and DK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. VL and LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

As this study is a scoping review, all relevant data are available in the included studies.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 407

Download: 17

Times Cited: 0