Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

Email: taylorlow@creighton.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3851-3532

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-9079-6139

Affiliation:

1Department of Medicine, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-0652-2848

Affiliation:

2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2676-2268

Explor Digit Health Technol. 2026;4:101176 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edht.2026.101176

Received: September 30, 2025 Accepted: November 12, 2025 Published: January 03, 2026

Academic Editor: Devesh Tewari, Delhi Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research University, India

Aim: The aim of this study is to compare the accuracy, reliability, and educational quality of YouTube videos on osteochondritis dissecans based on their YouTube Health verification status.

Methods: The term “osteochondritis dissecans” was searched on June 3, 2024. The first 50 videos found on YouTube after searching “osteochondritis dissecans” were evaluated. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria was used to score video reliability and accuracy (0–4 points), the Global Quality Score (GQS) was used to score nonspecific educational content (0–5 points), and the osteochondritis dissecans specific score (OCDSS) was used to score specific educational content (0–11 points). Three independent reviewers scored all videos, and interrater reliability was assessed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Group differences were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and independent sample t-tests, and multivariable linear regression was used to identify independent predictors of JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores.

Results: A total of 50 videos were analyzed with a cumulative 326,851 views. The mean JAMA score was 2.28 ± 0.64, the mean GQS score was 2.60 ± 1.36, and the mean OCDSS was 5.02 ± 3.16. The mean JAMA score for YouTube Health verified videos was 2.44 ± 0.34, GQS was 2.72 ± 1.22, and OCDSS was 5.72 ± 2.69. The mean JAMA score for videos not verified by YouTube Health was 2.29 ± 0.65, GQS score was 2.61 ± 1.44, and OCDSS was 4.95 ± 3.37. These differences were not statistically significant: JAMA p = 0.380, GQS p = 0.837, OCDSS p = 0.546.

Conclusions: There were no significant differences in reliability, educational content, and comprehensiveness between videos that were verified by YouTube Health and videos that were not verified.

The Internet is a popular source of health care information. In the United States, an estimated 95% of adults used the Internet in 2024, and 58.5% of adults reported using the Internet to access health or medical information [1, 2]. In a 2017 study, Americans reported using a vast number of Internet sources to obtain health-related information. These sources included commercial websites (71.8%), search engines (11.6%), academically affiliated sites (11.1%), and government-sponsored sites (5.5%) [3].

Traditional sources of information include consulting medical professionals. However, online platforms have become increasingly popular for patient education due to their accessibility and visual appeal [4]. YouTube is the most visited social media site in America, with an estimated 83% of the population visiting this site [5]. This platform is becoming increasingly more popular for accessing health-related information. The vast number of uploaded videos allows users to cross-check multiple videos to subjectively determine which information is reliable. A 2024 study found that out of 3,000 participants, 87.6% watch health-related content (HRC) and 40% of the users watch HRC to decide whether to consult a doctor or adopt certain practices [6]. Although videos are mainly verbal, they also contain a large portion of written information. Thus, the concept of health literacy becomes essential. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the American Medical Association (AMA) all recommend that patient education materials be written at or below a sixth-grade reading level to enhance comprehension and usability among the general population. The recommendation comes from research demonstrating that materials exceeding this readability threshold can hinder understanding and patient engagement [7]. Patient education plays a pivotal role in improving health outcomes by empowering individuals to understand and actively participate in their care. When patients understand the cause of their disease, as well as treatment options, they can participate in shared decision-making and comply with physician recommendations. This contributes to better disease management, reduced complications, and improved quality of life [8].

Despite the increasing use of online resources, there is an array of both high-quality and low-quality health-related videos available for users to access. Video quality according to users may be evaluated using criteria such as credibility of the source and overall content usefulness [9]. As a result, users are left to decide which information is reliable. Previous studies on the educational accuracy of YouTube videos have been conducted on orthopedic conditions and topics such as hip and knee arthritis, lumbar discectomies, articular cartilage defects, and more [10–15]. Results from these studies indicate that videos uploaded to YouTube have poor educational content. To help combat this issue, YouTube Health was recently launched with the goal of helping users find health information from authoritative sources. Currently, it is unknown whether the quality of verified videos is higher than that of unverified videos. To address this problem, this study assessed the educational content quality and reliability of YouTube Health verified and unverified videos, specifically osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), because it is a common cause of joint pain among children and necessitates early diagnosis and management.

OCD is a form of osteonecrosis that primarily affects school-aged children and adolescents. The highest incidence occurs between the ages of 12 and 19, and males have a 2–4 times higher incidence than females. However, the exact incidence of OCD is unknown [14]. The prevalence of OCD is between 9.5 and 29 per 100,000. The pathophysiology of OCD begins with the disruption of epiphyseal vessels, which causes ischemia and necrosis at the site of injury. The disease is most commonly due to repetitive trauma, but can also occur with isolated injury. Patients typically present with symptoms of poorly localized knee pain that worsens with physical activity. Patients may also experience stiffness and a locking sensation. The initial assessment of OCD involves plain radiographs to locate the lesion and rule out other causes. MRI is the most valuable diagnostic imaging technique used to diagnose OCD when plain radiographs are negative, but the clinical suspicion remains high. The treatment has either a conservative or surgical approach, depending on the patient’s age and the severity of the disease. Nonoperative treatment is considered for patients without a displaced fragment, whereas operative treatment is recommended if conservative measures are ineffective for 3–6 months. The prognosis of OCD is generally more favorable for juvenile patients compared to adults. If left untreated, adults with OCD can develop arthritis. Similar studies on higher-volume orthopedic topics such as the anterior cruciate ligament, Achilles tendon, or knee osteoarthritis have been conducted, so the authors of this study chose OCD because, although less commonly discussed, it is still a clinically significant condition with limited patient education resources available online. Thus, it is essential to evaluate the accuracy and quality of the limited existing resources to ensure patients are adequately informed of the pathophysiology and treatment of the disease.

This study utilized a cross-sectional observational design. The authors of this study searched the term “osteochondritis dissecans” on June 3, 2024, in the Midwestern United States. Videos were reviewed and graded independently by three medical students. A Google Chrome incognito tab was used to eliminate any confounding factors influencing the results. The first 50 videos based on the key term were evaluated; this method has been reported as a viable method of video selection because this method of evaluation has been used in previous peer-reviewed literature in orthopedic surgery [15]. Videos included for initial review were limited to the first 50 videos that populated after searching the term “osteochondritis dissecans”. Exclusion criteria included videos in non-English languages, audio-only soundtracks, and OCD videos not relating to humans. In these cases, the next video that did not violate exclusion criteria was used.

Engagement characteristics such as views, likes, comments, and view ratio were reported. View ratio was measured as views per day since the video was uploaded to YouTube. YouTube removed its dislike count in 2021, so video characteristics that are reported in similar studies are not present. These include dislikes, like ratio [(likes × 100) (likes + dislikes)], and the video power index formula: like ratio × view ratio 100 [15].

Video upload sources were categorized into the following: academic (research group or affiliated with colleges/universities), physician (independent physician or physician groups with no research or university affiliation), nonphysician (health professionals not classified as medical doctors), athletic trainer, medical source (health website content), patients, or commercial. This method has been used in similar peer-reviewed studies [15].

Video content was categorized into exercise training, disease-specific information, patient experience, management techniques, or advertisements.

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria are a nonspecific tool used to assess the reliability and accuracy of each video. It consists of four standards: authorship, attribution, disclosure, and currency. A point was assessed for each criterion the video met. There was a maximum score of four and a minimum score of zero. A higher score represents a video with greater reliability and accuracy. This criterion is not validated but has been used in several previous studies to assess the reliability of online sources [15].

The Global Quality Score (GQS) was used to assess nonspecific educational quality. It is not validated but has been used in prior studies to assess the quality of online resources. GQS consists of five criteria ranging from poor quality to excellent quality. A maximum score of five indicates high educational quality, and a minimum score of zero indicates low educational quality [15].

To evaluate the educational content of OCD specifically, we created the osteochondritis dissecans specific score (OCDSS) that consists of eleven items based on guidelines from the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and based on concepts described in previous studies [15, 16]. The OCDSS evaluates information on patient presentation (2), information on OCD (2), diagnosis and evaluation (5), and treatment (2) (Table 1). One point is assigned for each item present. The maximum score of eleven indicates a video with more comprehensive coverage of OCD presentation, pathology, and treatment, while a minimum score of zero indicates a video with zero to minimal coverage of OCD presentation, pathology, and treatment.

Osteochondritis dissecans specific scores (OCDSS), developed by the authors.

| Osteochondritis dissecans specific score categories |

|---|

| Patient presentation (2 points total) |

| Describes symptoms (1 point) |

| Describes patient population (1 point) |

| Information on OCD (2 points total) |

| Describes anatomy (1 point) |

| Describes causes of OCD (1 point) |

| Diagnosis and evaluation (5 points total) |

| Describes physical exam (tenderness, effusion, loss of motion, or crepitus) (1 point) |

| Mentions limitations of X-ray for diagnostic purposes (1 point) |

| Mentions use of MRI as gold standard (1 point) |

| Describes surgical candidates (1 point) |

| Describes nonsurgical candidates (1 point) |

| Treatment (2 points total) |

| Describes surgical treatment (1 point) |

| Describes nonsurgical treatment (1 point) |

One point is assigned for each criterion met by the video (maximum 11, minimum 0). Inspired by previous studies [15]. OCD: osteochondritis dissecans.

All statistical analysis was performed using Python Software Foundation (version 3.11) https://www.python.org/. Descriptive statistics were calculated for reliability (JAMA), educational quality (GQS), and content comprehensiveness (OCDSS), as well as engagement metrics (views, likes, comments, video power index). Interrater reliability between reviewers was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores across uploader source categories (academic, physician, medical source, patient, and commercial) and content categories (exercise/rehabilitation, disease-specific information, patient experience, management techniques, advertisements). Independent sample t-tests compared YouTube Health verified versus non-verified videos. Multivariable linear regression models were fitted with JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS as dependent variables; predictors included uploader source, content category, YouTube Health verification status, log-transformed view counts, and video duration. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

52 videos were screened because two videos met the exclusion criteria. One video was excluded because it was about OCD in dogs, and the other video was excluded because it was audio-only. Of the 50 videos regarding OCD, the mean number of views was 6,537 ± 7,974. These videos had a cumulative total of 326,851 views, and video characteristics are listed in Table 2.

YouTube video characteristics.

| Engagement metric | Mean ± SD (range) |

|---|---|

| Views | 6,537 ± 7,974 (7–40,528) |

| Likes | 64.9 ± 115.5 (0–752) |

| Comments | 16.0 ± 36.1 (0–211) |

| View ratio | 3.51 ± 4.52 (0–28.97) |

| Video parameters | |

| Duration (seconds) | 366 ± 298 (14–4,518) |

| Days since upload | 2,112 ± 1,275 (69–5,209) |

| Scoring system | |

| JAMA (0–4) | 2.28 ± 0.64 (0.62–3.67) |

| GQS (1–5) | 2.60 ± 1.36 (0.67–5.00) |

| OCDSS (0–11) | 5.02 ± 3.16 (0–10.33) |

GQS: Global Quality Score; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association; OCDSS: osteochondritis dissecans specific score.

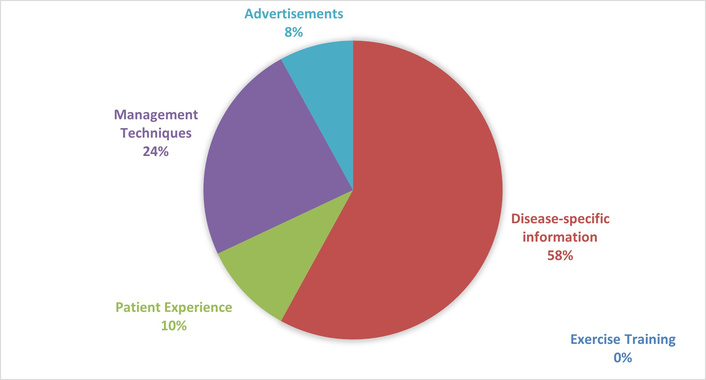

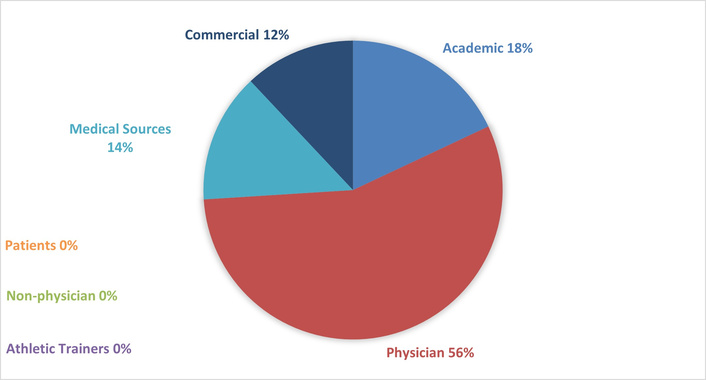

The most common information presented was disease-specific information (58%), followed by management techniques (24%), patient experience (10%), and advertisements (8%) (Figure 1). The most common source of videos was physicians (56%), followed by academic sources (18%), medical sources (14%), and commercial (12%) (Figure 2).

Relative frequencies of video content for OCD-related YouTube videos. OCD: osteochondritis dissecans.

Relative frequencies of video uploader sources for OCD-related YouTube videos. OCD: osteochondritis dissecans.

The ICC for JAMA was 0.36 (p = 0.02), GQS was 0.86 (p < 0.001), and OCDSS was 0.89 (p < 0.001).

Videos uploaded by academic and physician sources had higher JAMA scores, and videos uploaded by patients or commercial sources had lower JAMA scores. None of the univariate differences in GQS or OCDSS scores were statistically significant (Table 3).

Mean JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores by uploader source.

| Uploader source | JAMA | GQS | OCDSS | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician | 2.51 ± 0.69, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 2.96 ± 1.47, median 3.0 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 5.67 ± 3.51, median 5.0 (IQR 3.0–7.0) | 28 |

| Academic | 2.26 ± 0.46, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 2.41 ± 1.14, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 4.93 ± 3.48, median 6.0 (IQR 4.0–8.0) | 9 |

| Medical source | 1.90 ± 0.32, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–2.5) | 2.52 ± 1.62, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 4.81 ± 3.48, median 5.0 (IQR 3.0–6.0) | 7 |

| Commercial | 1.89 ± 0.17, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–2.0) | 1.44 ± 0.40, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–2.5) | 2.61 ± 1.39, median 4.0 (IQR 2.0–6.0) | 6 |

ANOVA results: JAMA (F = 3.40, p = 0.026), GQS (F = 2.18, p = 0.103), OCDSS (F = 1.50, p = 0.228). ANOVA: one-way analysis of variance; GQS: Global Quality Score; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association; OCDSS: osteochondritis dissecans specific score.

Disease-specific information had the highest mean JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores, while patient experience and advertisement videos had the lowest scores (Table 4).

Mean JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores by content category.

| Content category | JAMA | GQS | OCDSS | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-specific | 2.30 ± 0.56, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 3.25 ± 1.40, median 3.0 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 6.55 ± 3.20, median 6.0 (IQR 4.0–8.0) | 29 |

| Management techniques | 2.58 ± 0.82, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–2.5) | 2.03 ± 1.00, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 3.39 ± 2.33, median 5.0 (IQR 3.0–7.0) | 12 |

| Patient experience | 2.00 ± 0.33, median 2.0 (IQR 1.0–2.0) | 1.47 ± 0.38, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–2.5) | 2.33 ± 1.62, median 4.0 (IQR 2.0–5.0) | 5 |

| Advertisement | 1.92 ± 0.17, median 1.5 (IQR 1.0–2.0) | 1.25 ± 0.32, median 2.0 (IQR 1.0–2.5) | 2.50 ± 1.73, median 3.0 (IQR 2.0–4.0) | 4 |

ANOVA results: JAMA (F = 1.84, p = 0.153), GQS (F = 6.85, p = 0.001), OCDSS (F = 6.77, p = 0.001). ANOVA: one-way analysis of variance; GQS: Global Quality Score; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association; OCDSS: osteochondritis dissecans specific score.

Verified videos showed slightly higher JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores compared with unverified videos (Table 5). However, none of the scores were statistically significant on univariate analysis: JAMA p = 0.380, GQS p = 0.837, and OCDSS p = 0.546. Engagement metrics such as views, likes, comments, and video ratio did not differ significantly between groups: views p = 0.635, likes p = 0.262, comments p = 0.938, and view ratio p = 0.270.

Video characteristics comparison between YouTube Health verified and unverified videos.

| Measure | Verified (n = 6) | Unverified (n = 44) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| JAMA (0–4) | 2.44 ± 0.34, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 2.29 ± 0.65, median 2.0 (IQR 1.5–3.0) | 0.380 |

| GQS (1–5) | 2.72 ± 1.22, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 2.61 ± 1.44, median 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.0) | 0.837 |

| OCDSS (0–11) | 5.72 ± 2.69, median 6.0 (IQR 4.0–7.0) | 4.95 ± 3.37, median 5.0 (IQR 3.0–7.0) | 0.546 |

| Duration, seconds | 472 ± 349, median 143 (IQR 137–212) | 355 ± 292, median 251 (IQR 125–359) | 0.379 |

| Days since upload | 2,310 ± 1,360, median 2,127 (IQR 1,172–3,381) | 2,107 ± 1,342, median 1,705 (IQR 1,129–2,658) | 0.742 |

| Views | 7,411 ± 3,915, median 7,082 (IQR 4,775–10,304) | 6,418 ± 128, median 3,530 (IQR 1,167–8,294) | 0.635 |

| Likes | 40.50 ± 35.90, median 42.5 (IQR 9.0–65.0) | 68.30 ± 128.00, median 25.5 (IQR 8.0–60.0) | 0.262 |

| Comments | 8.50 ± 10.82, median 5.5 (IQR 0.0–12.5) | 16.95 ± 39.91, median 1.0 (IQR 0.0–13.0) | 0.938 |

| View ratio | 4.17 ± 3.65, median 2.9 (IQR 2.1–4.1) | 3.40 ± 4.90, median 2.4 (IQR 0.7–4.2) | 0.270 |

GQS: Global Quality Score; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association; OCDSS: osteochondritis dissecans specific score.

YouTube Health verification status was significantly associated with both uploader source and content category. Among uploader sources, five out of six verified videos came from academic sources (p < 0.001). Physicians and commercial sources had no verified videos. In terms of content categories, patient experience and disease-specific information were more likely to be verified (p = 0.004). None of the management techniques or advertisement videos were verified.

In multivariable linear regression, video duration was associated with higher scores across all three outcome measures. Each additional minute of duration predicted an increase in JAMA (+0.02, p = 0.005), GQS (+0.04, p = 0.001), and OCDSS (+0.10, p = 0.002).

YouTube Health verification was an independent predictor of higher JAMA scores (β = +0.66, 95% CI 0.04–1.28, p = 0.036). Verification status did not significantly predict GQS (p = 0.14) or OCDSS (p = 0.09).

Uploader source and content category did not remain significant predictors in the adjusted models despite showing differences in univariate analysis. Log-transformed view counts were not associated with any outcome measure.

The first 50 videos had a cumulative total of 326,851 views, a mean of 6,537 views, and a range of 7 to 40,528 views when the search was conducted. Previous studies on the quality of YouTube content on orthopedic content, such as hip and knee arthritis, lumbar discectomies, and articular cartilage defects, were viewed more times and had a higher average number of views per video [17]. This suggests that there is less content regarding OCD on YouTube compared to more mainstream orthopedic conditions, such as posterior cruciate ligament injuries and Achilles tendon injuries. This may be attributed to several factors. There are limited diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic studies regarding OCD. OCD is a relatively uncommon disease, and the appropriate treatment is largely unknown. Thus, there may be limited educational content available for the public because of the lack of sufficient evidence.

The authors of this study found that the accuracy and reliability of YouTube videos regarding osteochondritis is low. The mean JAMA benchmark criteria score was 2.28 out of 4, which suggests the reliability of individual YouTube videos is moderate to low. The mean GQS was 2.60 out of 5. This suggests that the nonspecific educational content quality of YouTube videos is low, and viewers are not likely to be adequately informed about OCD based on the video. The mean OCDSS was 5.02 out of 11. This suggests that the specific educational content in individual videos is not comprehensive to inform viewers of the pathology, symptoms, and treatment options. These findings of low-quality YouTube videos regarding orthopedic conditions are similar to previous studies [18]. McMahon et al. [18] found that the mean JAMA benchmark score was 2.69, the mean GQS was 2.64, and the mean Achilles tendon specific score (ATSS) was 4.66.

Although physician and academic sources, as well as disease-specific videos, appeared to produce higher scores, these associations were only statistically significant in univariate analyses. Specifically, the uploader source was significantly associated with higher JAMA scores, and the content category was significantly associated with higher GQS and OCDSS. However, once we adjusted for other variables in multivariable regression, these differences no longer remained significant. This suggests that factors such as video length and verification status are more important predictors of reliability and quality. Longer videos consistently achieved higher scores across all three evaluation systems. Video popularity, as measured by views, likes, comments, and video power index, was not significantly associated with any scoring system. The average number of views per video was high, but this was driven up by a few highly popular videos. The median view count was lower, reflecting that most videos had relatively low to moderate engagement. The disconnect between popularity and quality highlights a potential risk for patients, as highly viewed videos are not necessarily the most reliable or comprehensive sources of information. It is reasonable to assume users who search for health content on YouTube rarely scroll past the first few pages of videos that populate when they enter their search term. Users look for relevant videos based on characteristics such as title, viewer engagement, or content. The results of this study suggest that users should watch videos based on video length and YouTube Health verification status rather than looking at the title or who uploaded the video.

When comparing YouTube Health verified versus unverified videos, verified videos demonstrated slightly higher mean JAMA, GQS, and OCDSS scores. However, these differences were not statistically significant in unadjusted analyses. Engagement metrics including views, likes, comments, and video power index, also did not differ significantly between groups. Notably, verified videos were significantly shorter in duration than unverified videos. In multivariable regression, YouTube Health verification was a statistically significant independent predictor of higher JAMA reliability scores, but it did not significantly predict GQS or OCDSS. Verification status was not randomly distributed across the dataset. Verified videos were disproportionately uploaded by academic sources. While this discrepancy exists, it is a positive sign that YouTube Health is verifying videos from trustworthy sources, such as Stanford Medicine, Scottish Rite Hospital, and board-certified physicians. Likewise, verification was more common in patient experience and disease-specific information videos. These findings suggest that YouTube Health verification may serve as a meaningful marker of reliability, particularly for features such as authorship, disclosure, and transparency. However, verification alone does not guarantee higher overall quality or content comprehensiveness. In conclusion, these results indicate that while verification is a step toward improving the reliability of HRC on YouTube, additional measures may be required to enhance educational quality and comprehensiveness for patients.

For viewers to be accurately educated through YouTube, we believe videos should address points addressed by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons because this data is peer-reviewed. This is reflected in the OCDSS we created. Since scores suggest low-quality educational content and reliability, we recommend physicians to counsel patients on the low-quality YouTube videos regarding OCD and provide patients with accurate information and enable patients to take more control over their care.

While YouTube continues to be one of the most frequently accessed platforms for obtaining health-related information through videos, the landscape of online health education has expanded with the development of AI-powered conversational models and specialized web-based platforms. YouTube primarily provides user-generated video content, and the quality of information depends on the expertise of the content creator. In contrast, AI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Perplexity are interactive and generate real-time responses to user queries. These platforms utilize large language models to synthesize relevant information and provide readable health explanations. However, concerns remain regarding content reliability, accuracy, and source transparency. A recent study comparing AI systems found that although responses were easily readable, there was variability in accuracy and reliability [7]. Prior analyses of traditional online resources revealed that web-based education materials vary in quality and reliability. This demonstrates the ongoing challenge of ensuring online resources that are available for anyone to access are accurate and reliable.

The educational content quality and reliability of YouTube videos regarding OCD are low, and no significant differences exist between YouTube Health verified and unverified videos in terms of reliability, content quality, and comprehensiveness. This study highlights that video duration and YouTube Health verification are more reliable indicators of quality than popularity, uploader source, or content category. Future studies should look at more common orthopedic conditions to see whether YouTube Health verification affects the quality and reliability. Although we analyzed the first 50 videos, some videos had as low as 7 views, and it was obvious that the quality of the videos was decreasing the closer we got to 50 videos. This is most likely due to the low prevalence of this disease. Thus, it would be interesting to conduct this study with a more popular orthopedic condition, such as ACL injuries, Achilles tendon injuries, and knee arthritis, to identify if YouTube Health verified videos are more accurate and reliable than non-verified YouTube Health videos.

Currently, it is unknown whether videos verified by YouTube Health have better quality and reliability than non-verified videos. This is the first study of its kind to evaluate whether YouTube Health verifies videos with more reliable educational content. In addition, the ICC for GQS and OCDSS were excellent at 0.86 and 0.89, respectively. Taking these scoring criteria into consideration, the inter-observer reliabilities suggest that the analysis of educational quality was excellent.

This study was limited to the first 50 videos queried using the term “osteochondritis dissecans”. In addition, there were only six YouTube Health verified videos. Although the sample size was limited, we believe this reflects common search patterns used by YouTube users because users rarely scroll beyond the first few pages. Regarding YouTube Health verification, the platform was recently launched, which may account for the low number of verified videos. Because data collection was limited to a single day and region, the sample may not reflect the diversity of YouTube content globally or over time, which introduces potential confounding and selection bias. In addition, the ICC for JAMA benchmark criteria was 0.36, which suggests that raters may have had different interpretations of what met JAMA benchmark criteria. Furthermore, the OCDSS was developed specifically for the study to provide a standardized framework for evaluating educational content regarding OCD. Similar methodology has been used in previous peer-reviewed studies. However, the instrument has not undergone comprehensive validation, and therefore, findings derived from OCDSS scoring should be interpreted with caution until further validation studies establish its reliability and broader applicability.

ANOVA: one-way analysis of variance

GQS: Global Quality Score

HRC: health-related content

ICC: intraclass correlation coefficients

JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association

OCD: osteochondritis dissecans

OCDSS: osteochondritis dissecans specific score

TML: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft. JL and DN: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. DC: Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Project administration. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

No funding was used for this study.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 828

Download: 32

Times Cited: 0