Affiliation:

1Comprehensive Integrated Pain Program—Interventional Pain Service, Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON M5T 2S8, Canada

2Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5T 2S8, Canada

3Temerty Faculty of Medicine, Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3K3, Canada

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5518-3797

Affiliation:

1Comprehensive Integrated Pain Program—Interventional Pain Service, Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON M5T 2S8, Canada

2Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5T 2S8, Canada

Email: Philip.Peng@uhn.ca

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1704-7991

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2025;3:1007110 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2025.1007110

Received: August 28, 2025 Accepted: November 26, 2025 Published: December 05, 2025

Academic Editor: Fernando Pérez-Ruiz, Cruces University Hospital, Spain

Adhesive capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, is characterized by pain and progressive restriction of both active and passive shoulder range of motion. The pathophysiology involves an initial inflammatory phase with elevated cytokines, followed by pathological fibrosis, capsular thickening, and contracture involving both intra- and extra-articular structures, including the coracohumeral ligament and rotator cuff interval. Diagnosis is primarily clinical. The traditional three-stage model, freezing, frozen, and thawing, has been challenged by recent evidence showing that spontaneous recovery is uncommon and that many patients do not fully regain shoulder function without active treatment. This paradigm change emphasizes the necessity of early and focused interventions to maximize functional recovery. While physiotherapy remains the mainstay of management, interventional procedures have gained prominence for their ability to reduce pain and facilitate rehabilitation. Interventional options include intra-articular corticosteroid injections, hydrodilatation, and suprascapular nerve blocks. This narrative review summarizes current evidence on interventional procedures for adhesive capsulitis, highlighting their mechanisms, techniques, and comparative efficacy.

Commonly known as frozen shoulder, adhesive capsulitis (AC) was first adopted by Julius Neviaser in 1945 to better reflect the underlying pathologic fibrosis accounting for the progressive loss of active and passive range of movement (ROM) [1]. The incidence is approximately 1% in the general population based on a large prospective longitudinal study of 315,308 patients over 3 years [2]. Typically, this condition affects individuals between 40 and 70 years, with women comprising nearly two-thirds of cases, and diabetes stands out as one of the most prominent risk factors [3]. Other associated conditions include thyroid disorders, cardiovascular disease, and prolonged immobilization.

Although AC is often self-limiting, recent evidence challenges this notion, showing that many patients experience persistent stiffness and functional limitations for years if not actively treated. As such, active management is essential to restore function and shorten disease duration. The natural history, previously conceptualized as the “freezing”, “frozen”, and “thawing” stages, does not consistently result in full recovery, prompting a paradigm shift toward early and targeted intervention. Pain, sleep disturbance, and disability often have a profound impact on patients’ daily functioning and psychological well-being, further emphasizing the need for timely management. Physiotherapy remains the cornerstone of management, with pharmacologic and interventional strategies, such as intra-articular steroid injections (IAIs), hydrodilatation, and suprascapular nerve blocks (SSNBs), used to reduce pain and facilitate rehabilitation. Surgical options, including manipulation under anesthesia or arthroscopic capsular release, are reserved for refractory cases.

Given the growing evidence supporting interventional procedures in improving pain relief, mobility, and overall outcomes, this narrative review summarizes current evidence on interventional procedures for AC, highlighting their indications, techniques, and comparative efficacy.

The diagnosis of AC is based on clinical examination and is characterized by a gradual onset of pain and progressive loss of both active and passive ROM with at least 25% reduction in ROM in at least two planes of shoulder movement compared to the contralateral side [4]. The latter is an important criterion as it differentiates from other painful shoulder conditions that affect more active than passive movement. However, there are a few caveats in the clinical diagnosis.

First, loss of both active and passive ROM can occur in some shoulder conditions, such as severe glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis [5]. Second, the significant loss of passive ROM reflects the underlying progressive fibrotic process with capsular thickening and contracture. However, an interesting study showed that muscle stiffness or guarding could be a factor [6]. The stiffness reflects both the underlying inflammatory/pain rather than fibrotic process or psychological factors such as fear avoidance or catastrophizing thinking [7]. The understanding of this is important as it can be a barrier for physiotherapy and prompt clinicians to consider additional interventions to lower these barriers. Lastly, the interobserver reliability of applying the clinical criteria to diagnose AC is moderate [8]. There was an attempt to determine some key clinical identifiers to aid clinical diagnosis some years ago, with a Delphi consensus among different disciplines of physicians and clinicians [9]. However, it was shown later in a validation study that these clinical identifiers were not reliable for diagnosing early AC [10]. Thus, imaging plays a supportive role in the diagnosis of AC, primarily to confirm clinical suspicion and exclude other causes of shoulder pain and stiffness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides the most specific findings, including thickening of the joint capsule and coracohumeral ligament (CHL), and decreased capsular volume. Ultrasound can also aid in diagnosis, showing thickening of the CHL, capsular thickening at the axillary recess, and hypervascularity of soft tissue within the rotator interval, reflecting fibrovascular inflammation [11].

The natural history of AC [12] is usually described in three overlapping stages: freezing, frozen, and thawing, which together give the impression of a predictable self-limiting course. The freezing stage (typically lasting 2–9 months) is marked by progressive onset of pain, accompanied by gradual loss of active and passive range of motion as synovial inflammation and capsular thickening develop. The frozen stage (4–12 months) is characterized by persistent stiffness with a plateau in pain intensity, reflecting fibrotic contracture of the capsule and reduced capsular volume. The thawing stage (lasting up to 24 months) involves gradual recovery of motion as capsular remodeling occurs and inflammation subsides. However, several longitudinal studies refuted the natural course [13, 14], and a systematic review revealed that this triphasic course is not universal [15]. Furthermore, recent evidence indicates that without supervised intervention, many patients experience residual pain or motion limitation. Nevertheless, this three-stage framework remains clinically useful for conceptualizing disease progression and tailoring treatment strategies according to the predominant pathophysiological phase.

AC starts with inflammation, which presents with pain, which can be quite intense. The inflammatory process results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, transforming growth factor-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor), which in turn lead to enhanced fibrotic proliferation [16, 17]. In this process, there is a dysregulated collagen synthesis as well as enhanced contractility of fibroblast (myofibroblast). This process leads to capsular thickening and contracture at different stages [16–18]. As a result, there is contracture of the capsule (obliteration of the axillary pouch), thickening of the CHL, and changes in the rotator cuff interval (capsular thickness, fat obliteration). The fibrotic process affects both intra-articular and extra-articular tissue, such as the CHL [11]. As a result, there is a profound stiffness of the shoulder.

Recent literature suggests certain chemical mediators, such as transforming growth factor-β, intracellular adhesion molecules-1, are upregulated, resulting in proliferation of the fibrotic process, and such mediator is seen in chronic inflammatory states. A strong association exists between diabetes mellitus and AC, with diabetic patients exhibiting a higher prevalence, prolonged disease course, and greater resistance to treatment. The underlying mechanism is thought to involve chronic low-grade inflammation and aberrant immune-mediated fibrotic responses. Persistent hyperglycemia induces non-enzymatic glycation of collagen, leading to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that increase cross-linking within the joint capsule, reducing elasticity and impairing remodeling. Moreover, AGEs interact with their receptors (RAGEs), promoting oxidative stress and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, which perpetuate synovial inflammation and fibroblast proliferation. This chronic inflammatory milieu results in capsular thickening and fibrosis characteristic of AC. Recent studies further suggest that the inflammatory and immune pathways in diabetic AC differ from idiopathic cases, with enhanced macrophage and T-cell activation, providing potential targets for novel anti-fibrotic therapies [16–18].

The mainstay of management is physiotherapy. Pharmacologic and intervention procedures serve to lower the barrier to make physiotherapy more effective. Rarely, some patients suffer from severe restriction of movement and require surgery, which can be manipulation under anesthesia or arthroscopic capsular release [19]. The types of intervention and when the intervention could be considered will be discussed below.

In general, the main target of intervention is the glenohumeral joint. However, there are different techniques and approaches.

The literature supports the role of IAI [20, 21]. The mechanism involves suppression of local inflammatory mediators, inhibition of synovial fibroblast proliferation, and reduction in capsular vascularity and fibrosis, resulting in pain reduction and improved range of motion. Systematic reviews clearly show that the application of IAI provides benefit in both pain and function in the short-term period [22, 23]. Unfortunately, the short term varies between literature, and it can be referred to as six weeks to two months. When comparing hydrodilatation with simple IAI, two major systematic reviews [21, 23] have demonstrated superior outcomes with hydrodilatation. One review reported greater short-term improvement in shoulder function [21], while the other found additional short-term benefits in pain reduction [23]. Some physicians deliberately use very high volume to rupture the capsule to allow extraarticular spread, yet it does not confer additional benefit [24]. The main reason is that the rupture usually occurs in the subscapular fossa and along the subacromial bursa, not the anterior capsule or rotator cuff interval, which is one of the main sites of pathology for AC [20].

Conventional intra-articular injection involves injecting a small volume (3–8 mL) of local anesthetic and steroid into the joint. The injectate serves to reduce the pain through the anti-inflammatory action of the steroid. Another technique is hydrodilatation, the philosophy of which is to mechanically stretch the thickened and contracted joint with hydraulic pressure of the injectate [20]. The injectate may include a mixture of local anesthetic, corticosteroid, and saline. The volume of injectate varies from 15 mL to even 100 mL, although most publications adopted the volume between 20 to 40 mL. Some investigators even deliberate to rupture the capsule to obtain maximum benefit with the capsular rupturing technique [20, 21].

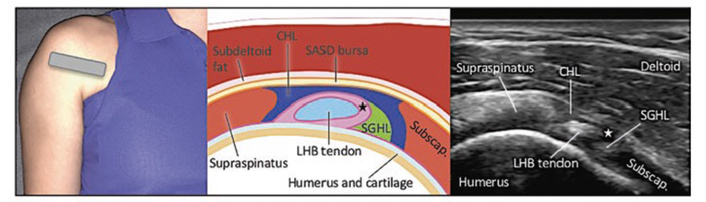

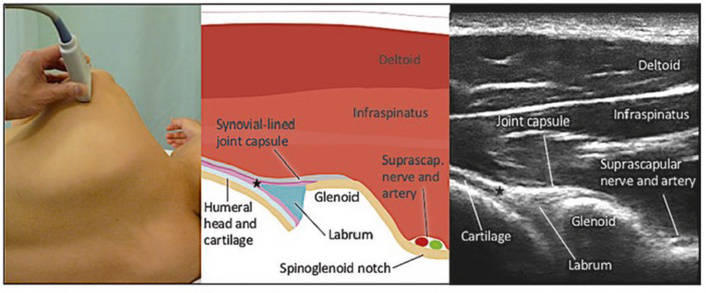

Two major approaches are commonly used for glenohumeral injection: the posterior approach and the rotator cuff interval (anterior) approach. In the posterior approach, the injectate is directly injected into the posterior glenohumeral joint (Figure 1), while in the rotator cuff interval approach, the needle is inserted into the anterior glenohumeral joint (Figure 2) [25]. A recent systematic review showed that the rotator cuff interval approach is superior pain and functional outcomes compared to the posterior approach [26]. Although the injectate of both approaches ends up in the glenohumeral joint, the difference is the pattern of spread. Both the cadaver study and in vivo studies showed that the rotator cuff interval approach allows direct delivery to the glenohumeral joint and pericapsular structures involved in AC, including the CHL [27, 28]. Several high-quality systematic reviews have synthesized the evidence for interventional management of AC, yet notable methodological and clinical heterogeneity persists across studies. Poku et al. [21] demonstrated that hydrodilatation offers short-term functional improvement compared to intra-articular corticosteroid injection, but the included trials varied considerably in distension volumes, injectate composition, and outcome measures, limiting comparability. Similarly, the network meta-analysis by Liang et al. [22] suggested potential advantages of corticosteroid injection via the rotator-interval approach; however, the certainty of evidence was downgraded due to small sample sizes and inconsistent follow-up durations. In contrast, Challoumas et al. [23] provided a broader synthesis of both conservative and procedural interventions but acknowledged substantial heterogeneity and a predominance of low- to moderate-quality randomized trials. Across these reviews, long-term outcomes beyond six months remain insufficiently reported, and few studies stratified results by disease stage or diabetes status. Collectively, these limitations highlight the need for standardized outcome measures, adequately powered comparative trials, and subgroup analyses to clarify the relative and temporal effectiveness of various interventional strategies.

Posterior view of the glenohumeral joint. (Figure reproduced with permission from Philip Peng Educational Series [36]).

Rotator cuff interval. (Figure reproduced with permission from Philip Peng Educational Series [36]).

SSNB is a common intervention procedure for various shoulder disorders [29]. It provides around 45% of the joint innervation in the superior and posterior aspect, as well as the surrounding tissue [30]. Importantly, it constitutes the main neural supply mediating nociception in both intra- and extra-articular shoulder structures [31]. A recent review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials involving 702 patients compared SSNB with other interventions for AC, including IAI, hydrodistension, and physiotherapy [32–34]. Results demonstrated that SSNB produced greater improvement in the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (mean difference = −4.75; 95% CI: −8.11 to −1.39; p = 0.006) and external rotation (mean difference = 11.64; 95% CI: −0.05 to 23.33; p = 0.05) compared with IAI. When used as an adjunct to physiotherapy, SSNB resulted in a statistically significant reduction in pain intensity [visual analog scale (VAS) mean difference = −0.31; 95% CI: −0.53 to 1.79; p = 0.004]. No serious adverse events were reported across studies. These findings support SSNB as a safe, effective, and minimally invasive option for managing AC, with outcomes comparable or superior to intra-articular corticosteroid injection based on level I evidence.

The mainstay of management for AC is physiotherapy. However, pain may impede rehabilitation in the early “freezing” phase. The need for intervention can be guided by tissue irritability levels, which reflect symptom severity and inflammatory activity [35]:

High irritability: High pain intensity (≥ 7/10), night pain, resting pain, high levels of reported disability on standardized self-reported outcomes, and marked ROM limitation. These patients often benefit from pharmacologic and interventional procedures to enable participation in physiotherapy.

Moderate irritability: Moderate pain (4–6/10), intermittent night or rest pain, pain mainly at end ranges, and moderate stiffness. Interventions may be considered at the provider’s discretion if physiotherapy progress stalls.

Low irritability: Minimal pain (≤ 3/10) and predominant stiffness without resting or night pain. Interventions are generally unnecessary.

Thus, interventional procedures are most beneficial for high- and selected moderate-irritability cases, either as an adjunct to or to facilitate physiotherapy.

Physiotherapy remains the foundation of treatment of AC, but adjunctive interventional procedures can provide meaningful short-term pain relief and functional improvement when pain limits physiotherapy participation. Evidence supports the short-term benefits of intra-articular corticosteroid injections, with hydrodilatation and rotator cuff interval approaches offering potential advantages in mobility and functional improvement. SSNBs show comparable efficacy to intra-articular injections for pain control, though further high-quality trials are needed to clarify their optimal role.

AC: adhesive capsulitis

AGEs: advanced glycation end products

CHL: coracohumeral ligament

IAIs: intra-articular steroid injections

ROM: range of movement

SSNBs: suprascapular nerve blocks

AA: Writing—review & editing. PP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft. Both of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 3753

Download: 46

Times Cited: 0